The Future of Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing & Journalism

140 Writing & Journalism Enroll at uclaextension.edu or call (800) 825-9971 Reg# 375735 Fee: $399 Writers’ Program No refund after 10 Nov. WRITING & ❖ Remote Instruction 6 mtgs Tuesday, 7-10pm, Oct. 27-Dec. 1 Creative Writing Enrollment limited to 15 students. c For help in choosing a course or determining if a Rachel Kann, MFA, author of the collection 10 for course fulfills certificate requirements, contact the Everything. Ms. Kann is an award-winning poet whose Writers’ Program at (310) 825-9415. work has appeared in various anthologies, including JOURNALISM Word Warriors: 35 Women Leaders in the Spoken Word Revolution. She is the recipient of the UCLA Extension Basics of Writing Outstanding Instructor Award for Creative Writing. These basic creative writing courses are for WRITING X 403 students with no prior writing experience. Finding Your Story Instruction is exercise-driven; the process of 2.0 units workshopping—in which students are asked to The scariest part of writing is staring at that blank page! share and offer feedback on each other’s work This workshop is for anyone who has wanted to write but with guidance from the instructor—is introduced. doesn’t know where to start or for writers who feel stuck Please call an advisor at (310) 825-9415 to deter- and need a new form or jumping off point for unique mine which course will best help you reach your story ideas. The course provides a safe, playful atmo- writing goals. sphere to experiment with different resources for stories, such as life experiences, news articles, interviews, his- WRITING X 400 tory, and mythology. -

Kathryn Tucker Windham

IRST RAFT FTHE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUMD VOL. 5, NO. 3 FALL 1998 Kathryn Tucker Windham: Also in this issue: MORE PLAYWRITING Page 6 Telling Stories of the South OPEN THE DOOR: Page 1 WORKS BY YOUNG WRITERS Page 9 AWF-AUM WRITERS’ AND ASSOCIATES’ COLLOQUIUM, ALABAMA VOICES, AND MORE! ROM THE XECUTIVE IRECTOR ALABAMA F E D WRITERS’ ctober 17, 1998, was a watershed day for poetry in Alabama. FORUM At the same time that the Alabama State Poetry Society was 1998-99 Board of Directors Ocelebrating its 30th anniversary with a daylong PoetryFest in President Birmingham–bringing together over 200 members and others to revel Brent Davis (Tuscaloosa) in the Word of poetry–Robert Pinsky, our U.S. Poet Laureate, was vis- Immediate Past President iting Montgomery to fulfill a dream of his own. Norman McMillan (Montevallo) Pinsky visited Montgomery to introduce a staged selection of his Vice-President translation of Dante’s “The Inferno” at the historic Dexter Avenue King Rawlins McKinney (Birmingham) Memorial Baptist Church, just one block from the state capitol. Secretary Jonathan Levi’s production, which features four actors and a violinist, Jay Lamar will travel to Miami, Kansas City, Seattle, Boston and back to New (Auburn) York (where it originated at the 92nd Street Y through the auspices of Treasurer Doug Lindley the Unterberg Poetry Center). Montgomery was the only deep South (Montgomery) stop for “The Inferno.” In the Winter First Draft, we will review the Co-Treasurer production at length. Edward M. George (Montgomery) Regrettably, these events (PoetryFest and “The Inferno” produc- Writers’ Representative Ruth Beaumont Cook tion) conflicted. -

FICTION EDITOR [email protected]

TL Publishing Group LLC PO BOX 151073 TAMPA, FL 33684 ALICE SAUNDERS EDITOR [email protected] AISHA MCFADDEN EDITOR [email protected] REBECCA WRIGHT EDITOR [email protected] ANNE MARIE BISE POETRY EDITOR [email protected] HEDWIKA COX FICTION EDITOR [email protected] TIFFANI BARNER MARKETING & NETWORKING SPECIALIST [email protected] AMANDA GAYLE OLIVER CONTENT WRITER [email protected] Official Website: http://www.torridliterature.com | http://tlpublishing.org Facebook Pages: http://www.facebook.com/torridliteraturejournal http://www.facebook.com/tlpublishing http://www.facebook.com/tlopenmic http://www.facebook.com/gatewayliterature Twitter: @TorridLit | @TLPubGroup Blog: http://torridliterature.wordpress.com To Submit: http://torridliterature.submittable.com/submit Torrid Literature Journal - Volume XV Untamed Creative Voices Copyright © 2015 by TL Publishing Group LLC All rights belong to the respective authors listed herein. All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-0692482636 ISBN-10: 0692482636 Customer Service Information: The Torrid Literature Journal is a literary publication published quarterly by TL Publishing Group LLC. To have copies of the Torrid Literature Journal placed in your store or library, please contact Alice Saunders. Advertising Space: To purchase advertising space in the Torrid Literature Journal, please contact Tiffani Barner at [email protected]. A list of advertis- ing rates is available upon request. Disclaimer: Any views or opinions presented or expressed in the Torrid Literature Journal are solely those of the author and do not represent those of TL Publishing Group LLC, its owners, directors, or editors. Rates and prices are subject to change without notice. For current subscription rates, please send an email to tljour- [email protected]. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

Amanda Nash Went Right to the Source: the Author

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 2 November 2003 74035 $4.00 In This Issue Even in the case of an artist like Louise Bourgeois, who has written extensively about the origins of her artworks in her life experience, the relationship between memory and art is never transparent or straight- forward, says reviewer Patricia G. Berman. Cover story D In The Fifth Book of Peace, her “nonfiction-fiction-nonfiction sandwich,” Maxine Hong Kingston experiments with new narrative forms, forgoing the excitement of conflict in an attempt to encom- pass the experience of peace and community. p. 5 Louise Bourgeois in her Brooklyn studio in 1993, with To find out what makes 3, Julie Shredder (1983) and Spider (then in progress). From Hilden’s novel of sexual obsession Runaway Girl: The Artist Louise Bourgeois and experimentation, so haunting, reviewer Amanda Nash went right to the source: The author. Art and autobiography Interview, p. 11 by Patricia G. Berman Could Hillary Rodham Clinton Three books examine the career of artist Louise Bourgeois became America’s first woman presi- dent? Judith Nies reads the senator’s n Christmas day 2003, the artist like environment suggestive of pulsating memoir Living History—along with Louise Bourgeois will turn 92. Her viscera, and I Do, I Undo, I Redo (2000), the other new books that examine O vitality, wit, and ability to fuse titanically scaled steel towers that initiated excess with elegance continue to rival the the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in women’s political leadership in this works of artists one-third her age. -

1953 the Mountaineers, Inc

fllie M®��1f�l]�r;r;m Published by Seattle, Washington..., 'December15, 1953 THE MOUNTAINEERS, INC. ITS OBJECT To explore and study the mountains, forests, and water cours es of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of North west America; to make expeditions into these regions in ful fillment of the above purposes ; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of out-door life. THE MOUNTAINEER LIBRARY The Club's library is one of the largest mountaineering col lections in the country. Books, periodicals, and pamphlets from many parts of the world are assembled for the interested reader. Mountaineering and skiing make up the largest part of the col lection, but travel, photography, nature study, and other allied subjects are well represented. After the period 1915 to 1926 in which The Mountaineers received books from the Bureau of Associate Mountaineering Clubs of North America, the Board of Trustees has continuously appropriated money for the main tenance and expansion of the library. The map collection is a valued source of information not only for planning trips and climbs, but for studying problems in other areas. NOTICE TO AUTHORS AND COMMUNICATORS Manuscripts offered for publication should be accurately typed on one side only of good, white, bond paper 81f2xll inches in size. Drawings or photographs that are intended for use as illustrations should be kept separate from the manuscript, not inserted in it, but should be transmitted at the same time. -

The Great White Mountains of the St Elias

PAUL KNOTT The Great White Mountains of the St Elias he St Elias range is a vast icy wilderness straddling the Alaska-Yukon T border and extending more than 200km in each direction. Its best known mountains are St Elias and Logan, whose scale is among the largest anywhere in terms of height and bulk above the surrounding glacier. Other than the two standard routes on Mount Logan, the range is still travelled very little in spite of ready access by ski plane. This may be because the scale, combined with challenging snow conditions and prolonged storms, make it a serious place to visit. Typically, the summits are buttressed by soaring ridges and guarded by complex broken glaciers and serac-torn faces. Climbing here is a distinctive adventure that has attracted a dedicated few to make repeated exploratory trips. I hope to provide some insight into this adventure by reflecting on the four visits I have enjoyed so far to the range. In 1993 Ade Miller and I were inspired by pictures of Mount Augusta (4288m), which not only looked stunning but also had obvious unclimbed ridges. Arriving in Yakutat (permanent population 600) we were struck by the enthusiasm and friendliness of our glacier pilot, Kurt Gloyer. There were few other climbers and we prepared our equipment amongst bits of plane in the hangar. Landing on the huge Seward glacier, we stepped out of the plane into knee-deep snow. It took some digging to find a firm base for the tents. Our first attempt to move anywhere was thwarted when Ade fell into an unseen crevasse 150m from the tents. -

Land Use and Economic Development Analysis October 2011

North Corridor Commuter Rail Project Land Use and Economic Development Analysis October 2011 Charlotte Area Transit System 600 East Fourth Street, Charlotte, NC 28202 Charlotte Area Transit System North Corridor Commuter Rail Project LYNX RED LINE Charlotte Area Transit System North Corridor Commuter Rail Project LYNX RED LINE Land Use and Economic Development Analysis This report is prepared by the Charlotte Area Transit System and Planning Staffs of the City of Charlotte and the Towns of Cornelius, Davidson, Huntersville and Mooresville. The information is structured according to guidelines of the Federal Transit New Starts Program, in the event the North Corridor Com- muter Rail Project becomes eligible for competition in that program. October 2011 Contents Section I: Existing Land Use ........................................................................................................... 1 Existing Station Area Development ............................................................................................ 1 1. Corridor and Station Area Population, Housing Units and Employment .......................... 1 Table I-1: Population Growth of Municipalities Represented in North Corridor ........... 3 Table I-2: Station Area Summary Data ............................................................................ 3 2. Listing and Description of High Trip Generators .............................................................. 4 3. Other Major Trip Generators in Station Areas .................................................................. -

Fall Course Listing Here

FALL QUARTER 2021 COURSE OFFERINGS September 20–December 12 1 Visit the UCLA Extension’s UCLA Extension Course Delivery Website Options For additional course and certificate information, visit m Online uclaextension.edu. Course content is delivered through an online learning platform where you can engage with your instructor and classmates. There are no C Search required live meetings, but assignments are due regularly. Use the entire course number, title, Reg#, or keyword from the course listing to search for individual courses. Refer to the next column for g Hybrid Course a sample course number (A) and Reg# (D). Certificates and Courses are taught online and feature a blend of regularly scheduled Specializations can also be searched by title or keyword. class meetings held in real-time via Zoom and additional course con- tent that can be accessed any time through an online learning C Browse platform. Choose “Courses” from the main menu to browse all offerings. A Remote Instruction C View Schedule & Location Courses are taught online in real-time with regularly scheduled class From your selected course page, click “View Course Options” to see meetings held via Zoom. Course materials can be accessed any time offered sections and date, time, and location information. Click “See through an online learning platform. Details” for additional information about the course offering. Note: For additional information visit When Online, Remote Instruction, and/or Hybrid sections are available, uclaextension.edu/student-resources. click the individual tabs for the schedule and instructor information. v Classroom C Enroll Online Courses are taught in-person with regularly scheduled class meetings. -

Inmemoriam1994 316-334.Pdf

In Memoriam TERRIS MOORE 1908-1993 Terris Moore, age 85, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, explorer, mountaineer, light-plane pilot and President Emeritus of the University of Alaska, died on November 7 after a massive heart attack. He became internationally known in 1932 when he and three companions reached and surveyed Minya Konka (now called Gongga Shan) in Sichuan, China. Moore and Richard Burdsall, both AAC members, ascended this very difficult mountain (that Burdsall and Arthur Emmons surveyed as 24,490 feet high), and in doing so climbed several thousand feet higher than Americans had gone before. At the time, Moore was the outstanding American climber. Moore, Terry to his friends, was born in Haddonfield, New Jersey, on April 11, 1908 and attended schools in Haddonfield, Philadelphia and New York before entering and graduating from Williams College, where he captained the cross-country team and became an avid skier. After graduating from college, he attended the Harvard School of Business Administration, from which he received two degrees: Master of Business Administration and Doctor of Commercial Science. Terry’s mountain climbing had begun long before this time. In 1927, he climbed Chimborazo (20,702 feet) in Ecuador and made the first ascent of 17,159-foot Sangai, an active volcano there. Three years later, he joined the Harvard Mountaineering Club and also became a member of the American Alpine Club, connections which led that year to his making the first ascent of 16,400-foot Mount Bona in Alaska with Allen Carp& and the first unguided ascent of Mount Robson in the Canadian Rockies. -

Project Blue Lynx an Innovative Approach to Mentoring and Networking Maj

TRANSFORMATION Project Blue Lynx An Innovative Approach to Mentoring and Networking Maj. Dan Ward, USAF n February 2005, shortly after pinning on Major, I began conducting a some- what low-profile experiment called Project Blue Lynx I(PBL). The name is a play on words that refers to the "blue links" in a Web document. The objective was to foster the de- velopment of a networked cadre of innovative thought leaders. In this article, I’m throwing back the curtain and presenting the PBL methodology and some of the initial results in the hopes that others around the DoD may launch similar efforts. An Aptitude for Attitude The first step was to recruit the PBL members, so I spent several months getting to know the company-grade officers in things better. We were going to question hidden institu- my part of the Air Force Research Lab. I wasn’t looking tional assumptions, and we were going to challenge the for aptitude in the traditional sense; everyone around here status quo. We were going to explore some unusual, po- is tremendously smart, so intelligence is not exactly a tentially revolutionary ideas. In short, we were going to useful discriminator. Rather, I was seeking a particular at- try to change the world for the better. Everyone said yes. titude. To be specific, I was looking for something that was equal parts optimism, adventure-seeking, dissatis- “There Will Be Homework …” faction with the status quo, and open mindedness. I was Our hallway discussions were followed by a detailed e- more interested in personal chemistry than professional mail that explained the group’s operating principles (shown credentials, and in the end I selected eight people: four in the sidebar on the next page) and gave them their first lieutenants and four captains. -

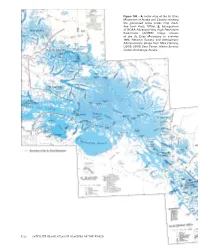

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St.