Proceedings of the 13Th Annual Convention: One English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concertos@Optimus Brings Cansei De Ser Sexy To

Lisbon, October 22 nd , 2008 CONCERTOS@OPTIMUS BRING S CANSEI DE SER SEXY TO PORTUGAL, TO LISBON AND OPORTO OPTIMUS CUSTOMERS WITH EXCLUSIVE ADVANTAGES: MEETINGS WITH THE BAND, SPECIAL SEATS AND POSSIBILITY OF INVITING FRIENDS • October 28 TH , Coliseu dos Recreios, Lisbon / October 29 TH , Teatro Sá da Bandeira, Oporto; • First part of the concerts taken over by the surprising X-WIFE; • Concerts with live coverage at musica.optimus.pt and also on Clix, Blitz, Antena 3 and RTP Online sites. Cansei de Ser Sexy will come to Portugal to performe on the 23rd concertos@optimus spectacle, a Sonae’s operator initiative that has shaken the entire musical scene. The Brazilians Cansei de Ser Sexy (CSS) obtained the revelation band status and will be in Lisbon and Oporto, for two unforgettable concertos@optimus. The group’s first performance will be already on October 28 th , at Coliseu dos Recreios, in Lisbon at 9pm. The next day, the band will be at Teatro Sá da Bandeira, in Oporto, for one more performance at 9pm. Before, the Portuguese X Wife will ensure both the Lisbon and Oporto’s first part of the concert. On both performances, Optimus Customers will have access to a unique set of advantages that will ensure even more unforgettable moments. Among the opportunities offered on Optimus site and the various contests promoted in the media are: • Privileged visibility - by creating a space near the stage, with capacity for about 400 customers winners of the contests; • Meet & Greet- private meetings with the band; • Optimus customers have the possibility of inviting and bringing up to 4 friends to the concert. -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 2006-07-11

DO NOT MISS TOMORROW’S DI IT’S A STORY OF PERSEVERANCE. A STORY OF PRIDE. A STORY YOU WILL ONLY FIND IN OUR PAPER. THE INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 The Daily Iowan TUESDAY, JULY 11, 2006 WWW.DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ Iowa Pierce might inmates receive parole graying Parole board members An increase flatly reject the notion in older inmates Pierce could live in any and the possible college town if released increase in health-care costs BY GRANT SCHULTE said after the hearing that THE DAILY IOWAN they frequently disagree. worry some Still, their support inches MOUNT PLEASANT — the ousted Hawkeye basket- BY ABIGAIL SAWYER State parole-board members ball star a step closer to free- THE DAILY IOWAN agreed Monday to vote for dom. If paroled, Pierce would Pierre Pierce’s early release remain under Department of From orange bellbottoms from prison but denied the Corrections supervision with to orange jumpsuits,it former Hawkeye basketball travel restrictions and a no- appears Iowa’s baby star’s plans to return to Iowa contact order with his victim, boomers are experiencing a City, declaring that his locat- while undergoing sex offend- new fashion trend, accord- ing in any college town is “not er “after care.” Robinson said ing to a new report. going to happen.” the board members expect to The number of the Instead, parole-board mem- decide within 30 days. state’s inmates age 51 and bers said, Pierce — serving a Pierce was sentenced to a older has increased 553 prison term for attacking his maximum of two two-year percent in the past 20 girlfriend in West Des Moines prison terms in October 2005, years, as reported by the — would likely have to live for convictions of assault with Iowa Department of with family in his native intent to commit sexual Human Rights’ Division of Westmont, Ill., if released. -

THE BARD OBSERVER Ltlilw."I May 3, 2006

N 0 0 °" THE BARD OBSERVER ltlilW."I May 3, 2006 Bard students who seemed happy enough just not to be in night with the arrival of the DJ. The ~A-run party was Spring Fling 2006 Kline. hopping, though the hopscotch was not. Evan Pritts, a member of the sound crew for the Sunday fea tured the inflatable games which are a Blue skies dispel winter Spring Fling music tent, said that the weekend went Spring Fling staple. Bard students and community chil ,..,..,...,_~ .. dren alike enjoyed the obstacle course, slide, moon bounce, ' .. and of course the gladiator's ring. Other students could be blues and bring Bard seen lying prone under the hot sun for hours, no doubt in shock that this could be the same campus which only students together weeks ago was frigid and inhospitable. Many vendors also lined the Qiad on Sunday, selling everything from cloth ing and jewelry, to henna tattoos, to toast. In addition, not one but two ice cream "trucks" capitalized on the warm BY CHRlSTINE NIELSEN weather, both run by enterprising Bard students. In the evening, after performances by the Flying Spring Fling was a hit among Bard students, owing in no Fiddlers and others, the weekend's musical selections small part to the weather, which was universally touted as wound to a close with an old favorite, the Foundation. "spectacular." Not a single cloud marred the sky from T hey were followed by a nighttime screening of Narnia, Friday to Sunday, and Bard's beautiful grounds put out projected drive-in style on the green and enjoyed by the their greenery just in time to celebrate. -

Culture Collide (LA) Corona Capital

o1*A *Añ ño1 1 *A ño ñ A o * 1 1 * A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A o ñ ñ o A 1 * * 1 A #o ñ ñ o A 1 1* Coberturas Especiales Culture Collide (L.A.) Corona Capital (D.F.) Editorial ™ Bienvenidos… La música forma parte fundamental del ser humano gracias al papel que ha jugado y juega en todas las culturas del mundo. Es una constante en la historia de la humanidad. Los instrumentos y sonidos podrán cambiar, pero en esencia siempre será expresión de emociones y sentimientos. México es el punto de enlace entre la música latinoamericana y la estadounidense; somos un país con un gran interés y pasión por la música de todas partes del continente y del orbe. Esa pasión se refleja en las bandas que crean canciones, remixes, covers, en los medios y sobre todo en la audiencia: que asiste a conciertos, busca lo más nuevo, pero que también celebra encontrarse en todo momento con las grandes bandas del pasado. Hoy, y tras una década de existencia, Filter Magazine, la publicación originaria de Estados Unidos, llega a México para compartir lo más actual y relevante, pero también para impulsar a las bandas referentes cuyo legado siempre está allí… esperando ser descubierto. Así que, es un honor presentarles el trabajo que después de varios meses de planeación se consagra en este primer número de Filter México, que cabe resaltar, será la primera publicación musical gratuita de nuestro país, porque sabemos que el modelo editorial tradicional no es viable para un melómano nómada. -

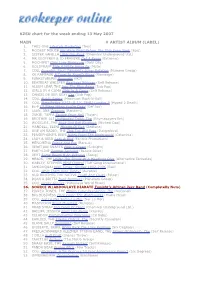

KZSU Chart for the Week Ending 13 May 2007 MAIN

KZSU chart for the week ending 13 May 2007 MAIN # ARTIST ALBUM (LABEL) 1. THES ONE Lifestyle Marketing (Tres) 2. MODEST MOUSE We Were Dead Before The Ship Even Sank (Epic) 3. SISTER VANILLA Little Pop Rock (Chemikal Underground Ltd.) 4. MR GEOFFREY & JD FRANZKE Get A Room (Extreme) 5. MOCHIPET Girls Love Breakcore (Daly City) 6. GOLDFRAPP Ride A White Horse Ep (Mute) 7. COLL Eccentric Soul: Twinight's Lunar Rotation (Numero Group) 8. KK RAMPAGE A Toast In Angel's Blood (Rampage) 9. FUNKSTöRUNG Appendix (!K7) 10. BEATBEAT WHISPER Beatbeat Whisper (Self Release) 11. ALBUM LEAF, THE Into The Blue Again (Sub Pop) 12. GIRLS IN A COMA Girls In A Coma (Self Release) 13. CANSEI DE SER SEXY Css (Sub Pop) 14. COLL Public Safety (Maximum Rock-N-Roll) 15. COLL Messthetics #102: D.I.Y. 78-81 London Ii (Hyped 2 Death) 16. EL-P I'll Sleep When You're Dead (Def Jux) 17. LAAN, ANA Oregano (Random) 18. ZUKIE, TAPPA Escape From Hell (Trojan) 19. BROTHER ALI Undisputed Truth, The (Rhymesayers Ent) 20. WOGGLES, THE Rock And Roll Backlash (Wicked Cool) 21. MANDELL, ELENI Miracle Of Five (Zedtone) 22. ONE AM RADIO, THE This Too Will Pass (Dangerbird) 23. PERSEPHONE'S BEES Notes From The Underworld (Columbia) 24. LADY & BIRD Lady & Bird (Fanatic Promotions) 25. MENOMENA Friend And Foe (Barsuk) 26. VENETIAN SNARES Pink + Green (Sublight) 27. PARTYLINE Zombie Terrorist (Retard Disco) 28. VERT Some Beans & An Octopus (Sonig) 29. HEADS, THE Under The Stress Of A Headlong Dive (Alternative Tentacles) 30. MARLEY, STEPHEN Mind Control (Tuff Gong International) 31. -

Conflito Entre Integrantes Do Css Causam Baixas No Grupo

CIRCUITOMATOGROSSO CULTURA EM CIRCUITO PG 6 CUIABÁ, 17 A 23 DE NOVEMBRO DE 2011 www.circuitomt.com.br evento dos festeiros de São Benedito de exalando, se mesclando numa sociedade na capital que compram joias caríssimas 2012, cujo cardápio será a deliciosa competitiva, mesquinha na qual o Real num valor bem alto só para aparições gastronomia árabe que reunirá boa parte fala mais alto. Com as senhoras com sociais e, muitas vezes, as peças não da cuiabania e da colônia árabe sob o quem convivi, aprendemos a respeitar ao fazem jus ao seu tipo físico. Joias de valor olhar atento de São Benedito. As famílias próximo, ter humildade e nos orientaram a é só de celebridade, que muitas vezes árabes que residem na capital têm uma dar umas alfinetadas de vez em quando fazem leilões para instituições filantrópicas. BALANÇO grande simpatia pelo Santo negro. nesta nova safra de emergentes que surge Contamos com a presença de todas as sem traquejo social, despreparados, hoje DA ÁGUA POTÁVEL DE famílias que contribuíram e até hoje tudo mudou, tendo dinheiro nas colunas O córrego da Prainha permitia a continuam contribuindo para o sociais só é aplausos e mais aplausos. entrada de pequenas embarcações até a desenvolvimento desse Estado. Praça do Iracatu, atual Ipiranga, ladeada Informações (65) 3322-5473/ (65)9208- VALOR SÓ NA VITRINE pelo córrego Cruz das Almas, em cujas 8512/(65)8115-9551. Ligue já. convites Nós estamos nos referindo às joias margens os homens vendiam seus limitados. Que o Santo negro abençoe a Por Carlinhos Alves Corrêa Por que encantam o ego humano e muitas pescados à população. -

College Voice Vol. 31 No. 11

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2006-2007 Student Newspapers 12-8-2006 College Voice Vol. 31 No. 11 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2006_2007 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 31 No. 11" (2006). 2006-2007. 12. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2006_2007/12 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2006-2007 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ... ~ First Class U.S. Postage PAID Permit #35 New London. cr PUBUSHED WEEKLY BYTNE STUDENTS OF CONNECTICUT COLLEGE VOLUME XXXI • NUMBER 11 FRIDAY,DECEMBER 8, 2006 CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LoNDON, CT Visiting Vet Discusses Need For US Policy Change In Iraq BY DASHA LAVRENNIKOV position and began to speak openly Iraq and provoked sectarian vio- against the war. He noted that it was lence. Iraqi casualties have reached newswrlter also at this time that the administra- 655,000, more than 500 people a tion of the United States announced day since the United States led inva- In a lecture organized by CC its lack of evidence of weapons of sion. Furthermore, this war has Left on Tuesday December 5th in mass destruction in Iraq. given the Iraqi people a common the Ernst Common Room, Charlie Anderson discussed the govern- enemy: the United States. There is a Anderson of Iraq Veterans Against ment's failure in properly preparing major confusion between the war the War spoke about his experiences soldiers for combat. -

O POP COMO TRANSGRESSÃO Luiza Vilela

O POP COMO TRANSGRESSÃO Luiza Vilela Março / 2012 PUC-Rio O POP COMO TRANSGRESSÃO CAETANO, TROPICÁLIA E EXÍLIO Luiza Vilela é produtora editorial e tradutora formada pela PUC-RIO. Passou um ano de sua graduação na University of Leeds e pesquisa poesia contemporânea no mestrado, também na PUC-RIO. E-mail: [email protected] Resumo Como seria possível resgatar o potencial transgressor da cultura pop? No presente artigo, volto aos anos de 1960 para entender como o pop, o popular e a cultura de massa foram misturados à alta cultura para gerar aquilo que foi a última vanguarda cultural brasileira, a Tropicália. Interesso-me menos pelo movimento em si, e mais pela maneira como Caetano conseguiu construir uma persona que resumia e teatralizava todas as influências, nacionais e estrangeiras, que corroboraram para aumentar o potencial transgressor da Tropicália. Esse retorno tem como objetivo buscar na música contemporânea indícios desse potencial transgressor, e tentar pensar como algumas bandas da cena atual releram essas influências. Abstract How would it be possible to redeem the transgressive potential of pop culture? In this article I look back to the 1960’s in order to understand how the pop, the popular and mass culture were blended together with high culture in order to create what was the last of the Brazilian avant-garde movements: the Tropicália. I am less interested in the movement itself than in the ways Caetano Veloso manages to build a persona who both summarized and theatricalized all of the influences – national and foreign – which helped boost Tropicália’s transgressive potential. -

The Ithacan, 2008-09-04

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 2008-09 The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 9-4-2008 The thI acan, 2008-09-04 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2008-09 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 2008-09-04" (2008). The Ithacan, 2008-09. 2. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2008-09/2 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 2008-09 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. OPINION STRAIGHT TALK NEEDED FROM SGA, PAGE 10 FALL FASHION HITS ITHACA SPORTS ITHACA STUDENTS INTERN AT OLYMPICS, PAGE 23 PlanPlan foforr brights,brigh plaids and lots of accessories, page 13 SPORTS FOUR BACKS VIE FOR STARTING POSITION, PAGE 24 Thursdayhursday Ithaca, N.Y. Septemberember 4,4 20082008 The Ithacan Volume 76, Issue 2 Investigation Questioning of reported rape continues BY ERICA R. HENDRY SPECIAL PROJECTS MANAGER An Ithaca College student study- ing in Los Angeles was arrested last week after a fellow student from the college filed a rape complaint against him. Dave Maley, associate director of media relations, said the col- lege’s program administration re- ceived the report last Tuesday, and the report may have been made to the Los Angeles Police Department and the college’s Los Angeles pro- gram staff and administration last Monday night. The student was charged under thedrinking Initiative sparks public the college’s student conduct code, Maley said. -

Titles Sep 28, 2021

All titles Sep 28, 2021 Name Description Rating Price ...By Request Boyzone Used £3.50 Dancefloor Anthems Various Artists Used £4.00 100 Greatest 90s / Various (Cd) Various Artists New £9.94 Dangerous Dancing Various Artists Used £3.50 100 Hits: 80s Essentials Various Artists Used £5.50 Dare To Dream Rebecca Newman Used £3.50 100% Clubland X-Treme Various Artists New £11.94 Dark Hope Renee Fleming Used £3.50 21 Adele Used £4.50 Dave Pearce Dance Anthems 2003 Various Used £5.00 2nd To None Elvis Presley Used £4.50 David Foster David Foster Used £2.50 3 Years 5 Months & 2 Days In The Life Of... Arrested Development Used £4.00 Decadance Bass In Yer Face Used £15.00 5 Classic Albums Bob Marley & The Wailers Used £20.00 Decadence Head Automatica Used £4.00 50 Lovely Irish Songs Shamrock Man Used £4.00 Dedicated Lemar Used £3.50 60's Beat Various Artists Used £5.00 Definitive Collection The Delfonics Used £3.50 7 Enrique Enrique Iglesias Used £3.00 Destination Ronan Keating Used £4.50 A Break In The Weather Ginger Used £17.50 Destiny Fulfilled Special Tour Edition Destiny's Child Used £4.50 A Funk Odyssey Jamiroquai Used £3.50 Diary Of Alicia Keys The Used £4.50 A Thousand Suns Linkin Park Used £5.00 Different Class Pulp New £8.94 Aaliyah Aaliyah Used £9.50 Dirty Dancing OST Various Artists Used £3.00 Abstract Innovations Q-Tip Used £16.50 Dis.Neyl.An.Daft.Erd.Ark D-A-D Used £13.50 Acting My Age The Academic Used £7.50 Documentary, The The Game New £11.94 After The Fire Cody Jinks New £14.94 Dream On Craig Chalmers Used £1.50 All Hope Is Gone -

Canciones De La Película

Octubre 2013 THE DICTATORS of NYC Dictators Forever CRÓNICAS: Texas Ten years after Stacie Collins Siniestro Total Los Rebeldes... Premier Metallica 3D Through the Never Entrevistas: Ariel Rot, La Fuga, J.Teixi Band 1 Portada de : Alex García THE DICTATORS OF NYC (Manitoba) Esta revista ha sido posible gracias a: Alex García Alfonso Camarero Caperucita Rock Chema Pérez David Collados Héctor Checa Jackster Javier G. Espinosa José Luis Carnes José Ángel Romera Kristina Espina Natalia Gürtner Nestor Daniel Carrasco Rafael Mozun Santiago Cerezo Victor Martín www.solo-rock.com se fundó en 2005 con la intención de contar a nuestra manera qué ocurre en el mundo de la música, poniendo especial atención a los conciertos. Desde entonces hemos cubierto la información de más de dos mil con- ciertos, además de informar de miles de noticias relacionadas con el Rock y la música de calidad en general. Solamente en los dos últimos años hemos estado en más de 600 conciertos, documentados de forma fotográfica y escrita. Los redactores de la web viven el Rock, no del Rock, por lo que sus opi- niones son libres. La web no se responsabiliza de los comentarios que haga cada colaborador si no están expresamente firmados por la misma. Si quieres contactar con nosotros para mandarnos información o promo- cional, puedes hacerlo por correo electrónico o por vía postal. Estas son las direcciones: Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Dirección Postal: Aptdo. Correos 50587 – 28080 Madrid 2 Sumario Crónicas de conciertos Pág. 4 Texas+Holy Bouncer+Girl Called Johnny Pág. 5 Ten Years After Pág. -

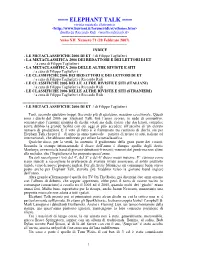

Classifiche 2006

=== ELEPHANT TALK === rivista musicale elettronica <http://www.burioni.it/forum/ridi/et/ethome.htm> diretta da Riccardo Ridi <mailto:[email protected]> -------------------------------------------------- Anno XII Numero 71 (28 Febbraio 2007) -------------------------------------------------- INDICE - LE METACLASSIFICHE 2006 DI ET / di Filippo Tagliaferri - LA METACLASSIFICA 2006 DEI REDATTORI E DEI LETTORI DI ET / a cura di Filippo Tagliaferri - LA METACLASSIFICA 2006 DELLE ALTRE RIVISTE E SITI / a cura di Filippo Tagliaferri - LE CLASSIFICHE 2006 DEI REDATTORI E DEI LETTORI DI ET / a cura di Filippo Tagliaferri e Riccardo Ridi - LE CLASSIFICHE 2006 DELLE ALTRE RIVISTE E SITI (ITALIANI) / a cura di Filippo Tagliaferri e Riccardo Ridi - LE CLASSIFICHE 2006 DELLE ALTRE RIVISTE E SITI (STRANIERI) / a cura di Filippo Tagliaferri e Riccardo Ridi -------------------------------------------------- - LE METACLASSIFICHE 2006 DI ET / di Filippo Tagliaferri Tanti, secondo qualcuno troppi. Secondo più di qualcuno, nessuno eccezionale. Questi sono i dischi del 2006 per Elephant Talk. Già l’anno scorso, in sede di consuntivo, constatavamo l’enorme quantità di dischi votati sia dalle riviste che dai lettori, complice senza dubbio la grande facilità con cui oggi si può accedere all’ascolto di un elevato numero di produzioni. E il voto di fatto si è frantumato tra centinaia di dischi, sia per Elephant Talk che per il – di anno in anno mutevole – paniere di riviste (e siti), italiane ed internazionali, che abbiamo utilizzato per stilare la metaclassifica. Qualche disco, per la verità, ha ottenuto il gradimento della gran parte dei votanti. Secondo la stampa internazionale il disco dell’anno è dunque quello degli Arctic Monkeys, ovverosia la band di giovani-debuttanti-frizzanti,-memori del punk-ma non alieni alla melodia, che l’Inghilterra ci ha proposto quest’anno.