An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Selective Breeding of Egg-Laying Hens for Productivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry

A GROWING PROBLEM SELECTIVE BREEDING IN THE CHICKEN INDUSTRY: THE CASE FOR SLOWER GROWTH A GROWING PROBLEM SELECTIVE BREEDING IN THE CHICKEN INDUSTRY: THE CASE FOR SLOWER GROWTH TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. 2 SELECTIVE BREEDING FOR FAST AND EXCESSIVE GROWTH ......................... 3 Welfare Costs ................................................................................. 5 Labored Movement ................................................................... 6 Chronic Hunger for Breeding Birds ................................................. 8 Compromised Physiological Function .............................................. 9 INTERACTION BETWEEN GROWTH AND LIVING CONDITIONS ...................... 10 Human Health Concerns ................................................................. 11 Antibiotic Resistance................................................................. 11 Diseases ............................................................................... 13 MOVING TO SLOWER GROWTH ............................................................... 14 REFERENCES ....................................................................................... 16 COVER PHOTO: CHRISTINE MORRISSEY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In an age when the horrors of factory farming are becoming more well-known and people are increasingly interested in where their food comes from, few might be surprised that factory farmed chickens raised for their meat—sometimes called “broiler” -

PLANT BREEDING David Luckett and Gerald Halloran ______

CHAPTER 4 _____________________________________________________________________ PLANT BREEDING David Luckett and Gerald Halloran _____________________________________________________________________ WHAT IS PLANT BREEDING AND WHY DO IT? Plant breeding, or crop genetic improvement, is the production of new, improved crop varieties for use by farmers. The new variety may have higher yield, improved grain quality, increased disease resistance, or be less prone to lodging. Ideally, it will have a new combination of attributes which are significantly better than the varieties already available. The new variety will be a new combination of genes which the plant breeder has put together from those available in the gene pool of that species. It may contain only genes already existing in other varieties of the same crop, or it may contain genes from other distant plant relatives, or genes from unrelated organisms inserted by biotechnological means. The breeder will have employed a range of techniques to produce the new variety. The new gene combination will have been chosen after the breeder first created, and then eliminated, thousands of others of poorer performance. This chapter is concerned with describing some of the more important genetic principles that define how plant breeding occurs and the techniques breeders use. Plant breeding is time-consuming and costly. It typically takes more than ten years for a variety to proceed from the initial breeding stages through to commercial release. An established breeding program with clear aims and reasonable resources will produce a new variety regularly, every couple of years or so. Each variety will be an incremental improvement upon older varieties or may, in rarer circumstances, be a quantum improvement due to some novel gene, the use of some new technique or a response to a new pest or disease. -

Born to Run: EVOLUTION: Variation and Natural Selection Artificial Selection Lab Two Versions of This Lesson by Theodore Garland, Jr., Ph.D

Born to Run: EVOLUTION: Variation and Natural Selection Artificial Selection Lab Two versions of this lesson by Theodore Garland, Jr., Ph.D. have been tested with 7th (University of California, Riverside) grade students by the second and Tricia Radojcic, Ph.D. author, and it has been used (Bella Vista Middle School, Murrieta, California) once at the Riverside STEM academy. SYNOPSIS Students are introduced to the field of experimental evolution by evaluating skeletal changes in mice that have been artificially selected over many generations for the behavioral trait of voluntary exercise wheel running. A video presentation by Dr. Theodore Garland, Jr. of the University of California, Riverside discusses the experimental design and presents the results of the collaborative research on the structural, metabolic, and neural changes in the selected lines of mice. In an inquiry-based activity, students develop hypotheses about the skeletal changes that might occur in the legs of the selected mouse populations and design an investigation using measurements taken from photographed femurs (thigh bones) of mice from both selected lines and non- selected control lines. PRINCIPAL CONCEPT Experimental evolution allows the processes of evolution to be modeled and observed in the laboratory with real organisms. ASSOCIATED CONCEPTS 1. A population of animals can be changed dramatically by selective breeding over successive generations. 2. Selective breeding for a behavioral trait also causes changes in neurobiology, body structures (e.g., limb bones), metabolism, and biochemistry. 3. Variation in behavioral traits and any other associated biological traits can be passed on from parents to their offspring. ASSESSABLE OBJECTIVES Students will.... 1. -

Science Worksheets Selective Breeding of Farm Animals; Food Chains and Farm Animals

Teachers’ Notes: Science Worksheets Selective Breeding of Farm Animals; Food Chains and Farm Animals Selective breeding and food Use with Farm Animals chains worksheets & Us films. We The Selective Breeding of Farm Animals worksheet recommend the first film Farm Animals & explains the basic process using chickens as an example. Us for students aged The worksheet also reinforces other biological concepts up to 14 or 15 and including genetic and environmental causes of variation, the more detailed mutations and natural selection. Farm Animals & Us 2 for abler and older The Food Chains and Farm Animals worksheet discusses students. energy losses in human food chains and pyramids of numbers. The DVD-ROM with these films is available Both worksheets raise ethical issues relating to science free to schools and and technology and encourage students to formulate can be ordered at their own opinions, especially in relation to the different ciwf.org/education. ways we use animals in producing food. The films can also be viewed online at ciwf.org/students. Selective breeding worksheet – suggested lesson plan: 1. Introduction. Explain an example of selective breeding, Crossword solution eg wheat plants have been selectively bred for yield, protein content, resistance to disease, flavour, to be good for making biscuits etc. Discuss the advantages of some of these. (2-3 minutes) 2. Discuss (small groups, then whole class) what chickens might be selected for (meat, fast growth, more breast meat, eggs, higher egg production, colour of eggs, larger or smaller eggs etc). (5-8 minutes) 3. Hand out worksheet. Read in silence, but allow discussion when they reach ethical points. -

Exploring Food Agriculture and Biotechnology 1

SCIENCE AND SCIENCE AND OUR FOOD SUPPLY Investigating Food Safety from FAR to OUR FOOD SUPPLYTABLE Simplified Steps of Plasmid DevelopmentExploring Food Agriculture and Biotechnology 1. Plasmid Cut with a 2. Plasmid and Desired Gene 3. Plasmid with Desired Restriction Enzyme Joined Using DNA Ligase Gene Inserted X P F1 X Selection Marker Gene Desired Gene That Sticky F2 Ligase was Cut with Same Restriction End Enzyme Restriction Enzyme Enzyme as the Plasmid Teacher’s Guide for High School Classrooms 1st Edition SCIENCE AND OUR FOOD SUPPLY Exploring Food Agriculture and Biotechnology Dear Teacher, You may be familiar with Science and Our Food Supply, the award-winning supplemental curriculum developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA). It uses food as the springboard to engage students in inquiry-based, exploratory science that also promotes awareness and proper behaviors related to food safety. FDA has developed a new component to the program: Science and Our Food Supply: Exploring Food Agriculture and Biotechnology —Teacher’s Guide for High School Classrooms, 1st edition. Designed to be used separately or in conjunction with the original program, this curriculum aims to help students understand traditional agricultural methods and more recent technologies that many farmers use today. The United States has long benefited from a successful agriculture system. However, with fewer people working on farms today compared to 100, or even 50, years ago, many American students do not fully understand how agriculture directly affects such aspects of their lives as food, health, lifestyles, and the environment. -

How Selective Breeding Has Changed the Morphology of the American Mink (Neovison Vison)—A Comparative Analysis of Farm and Feral Animals

animals Article How Selective Breeding Has Changed the Morphology of the American Mink (Neovison vison)—A Comparative Analysis of Farm and Feral Animals Anna Mucha 1, Magdalena Zato ´n-Dobrowolska 1,* , Magdalena Moska 1, Heliodor Wierzbicki 1 , Arkadiusz Dziech 1 , Dariusz Bukaci ´nski 2 and Monika Bukaci ´nska 2 1 Department of Genetics, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, 51-631 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 Institute of Biological Sciences, Cardinal Stefan Wyszy´nskiUniversity in Warsaw, 01-938 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71-320-5920 Simple Summary: Decades of selective breeding carried out on fur farms have changed the mor- phology, behavior and other features of the American mink, thereby differentiating farm and feral animals. The uniqueness of this situation is not only that we can observe how selective breeding phenotypically and genetically changes successive generations, but also that it enables a comparison of farm minks with their feral counterparts. Such a comparison may thus provide valuable infor- mation regarding differences in natural selection and selective breeding. In our study, we found significant morphological differences between farm and feral minks as well as changes in body shape: trapezoidal in feral minks and rectangular in farm minks. Such a clear differentiation between the two populations over a period of several decades highlights the intensity of selective breeding in Citation: Mucha, A.; shaping the morphology of these animals and gives an indication of the speed of phenotypic changes Zato´n-Dobrowolska, M.; Moska, M.; and the species’ plasticity. -

Biology 164 Laboratory Artificial Selection In

Biology 164 Laboratory Artificial Selection in Brassica, Part I (Based on a lab exercise originally developed by Bruce Fall, Univ. of Minnesota and revised by Tim Christensen, Colby College) I. Objectives 1. Understand the process of artificial selection. 2. Become familiar with some plant cultivars in the genus Brassica, which are the products of artificial selection. 3. Participate in an on-going artificial selection study involving three related cultivars of Brassica rapa in which you will: a. quantify the variability of a specific trait in the three cultivars, b. measure how the expression of the specific trait has responded to varying numbers of rounds of artificial selection, c. subject one of the cultivars to another round of artificial selection, and d. determine if there is evidence for an upper limit having been reached in the expression of the specific trait as additional rounds of artificial selection were employed. II. Introduction A visit to a farm, supermarket, pet store or plant nursery will offer many examples of selective breeding of plants and animals by humans. Over hundreds and even thousands of years, humans have altered various species of plants and animals for our own use by selecting individuals for breeding that possessed certain desirable traits. This selective breeding process was continued for generation after generation. Often the products of such selective breeding are remarkable. Quite diverse domestic dog breeds, from chihuahuas and miniature poodles to Newfoundlands and Irish wolfhounds are all related to a common wild ancestor, the wolf (Canis lupus). Domestic chickens are all derived from the wild Jungle Fowl (Gallus gallus). -

Lesson 6: Extend

27 Lesson 6: Extend Big Idea: Artificial selection is not a new or natural process. Artificial selection plays a large role in our agriculture production today. Lesson Objective: Students will justify if their design process was natural selection or artificial selection. Lesson Essential Question: When designing your organism to be the best suited for its environment was that natural selection or was it artificial selection? Materials Needed: Artificial Selection Reading Vocabulary: Lesson Flow: 1. Assessing Prior Knowledge (Engage) a. Teacher shows students pictures of wild strawberries vs store bought strawberries. i. http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-fDQBm9NDQI0/UbZ_0V- 4MoI/AAAAAAAADr0/F2rjZKgt8o4/s1600/strawberry+comparison.jpg b. Teacher poses the question “Why are these strawberries so different?” c. Students answer using prior knowledge and knowledge of natural selection. 2. Artificial Selection Reading (Explore) a. As students read they will use text tags to talk with the text. b. Students must use at least 5 text tags. c. Students will explain 3 of their text tags using the sentence starters. 3. Class Discussion (Explain) a. Discuss with students: i. Techniques for artificial selection 1. Crossbreeding 2. Genetic modification ii. Positives and Negatives to the environment iii. Positives and Negatives to the human race 4. What have we done? (Evaluate) a. Teacher poses the question “Think back to when we designed organisms to be best suited for their environment. Was this natural selection or artificial selection? Provide evidence to support your claim.” 28 Artificial Selection at Work http://www.learner.org/courses/essential/life/session5/closer1.html What is artificial selection? Artificial selection is the intentional reproduction of individuals in a population that have desirable traits. -

Selective Breeding

Selective Breeding Selective Breeding by ReadWorks Charles Darwin, a British naturalist who lived in the 19th century, is best known for his book On the Origin of Species. In it, Darwin established the idea of evolution that is widely accepted today. He proposed that all species alive have evolved through adaptation to their surroundings. Natural selection, the process by which varied traits that increase survival and enable reproduction are passed down from generation to generation, is probably the most famous principle from the book. Darwin's book also addresses the perhaps less well-known concept of artificial selection. Today artificial selection is more often called "selective breeding." Selective breeding involves breeding animals or plants for a specific, typically desirable trait. By doing so, the desired genes from the plant or animal will be passed on to its offspring. Dog breeding is one of the most common examples of artificial selection. You need only to tune into a dog show on TV to see the power of selective breeding at work. Crossbreeds, for example, are dogs born from parents of two different breeds. Mixed breeds are born from parents of more than two breeds, and pure breeds are born from a single breed. All three varieties are featured in most dog shows. Many of these dogs were bred to achieve certain desirable physical or behavioral traits. Beyond the context of dog shows, dogs are a particularly interesting example of selective breeding. After all, we call dogs "man's best friend" for a reason. Dogs originally evolved from wolves. Eventually, humans were breeding different types of dogs to accomplish certain jobs. -

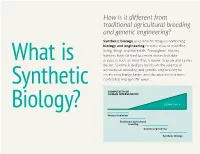

How Is It Different from Traditional Agricultural Breeding and Genetic

How is it different from traditional agricultural breeding and genetic engineering? Synthetic biology uses new techniques combining biology and engineering to make new or modified living things and materials. Throughout history, humans have strived to create more desirable What is products such as food that is easier to grow and tastes better. Synthetic biology builds on the science of agricultural breeding and genetic engineering to create new things faster and cheaper in even more Synthetic controlled and specific ways. COMPLEXITY OF HUMAN INTERVENTION Biology? COMPLEXITY Natural evolution Traditional agricultural breeding Genetic engineering Synthetic biology Genes & DNA The building blocks of all life Genes are a set of instructions that determine how a living organism forms and grows. Genes influence what we look like on the outside and how we work on the inside. Genes are made of a chemical called DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA molecules are located inside a cell nucleus; DNA carries information and can copy itself. Adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G) are the four nucleotides found in DNA. CELL GENE DNA CHROMOSOME Timeline How genetic manipulation has evolved 10,000 LATE YEARS 1859: 1980s: 1990s: 2013: AGO: Charles Darwin First genetically Genetically Synthetic Humans publishes "The engineered engineered biology begin using Origin of the plants developed foods (GMOs) scientists raise selective Species” on the are available in funds using breeding theory of grocery stores Kickstarter to improve evolution by in -

Progress Over 20 Years of Selective Breeding

The Quagga project: progress over 20 years of selective breeding Eric H. Harley1*, Michael H. Knight2, Craig Lardner3, Bernard Wooding4 & Michael Gregor4 1Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, University of Cape Town, Observatory, 7925 South Africa 2South African National Parks, P.O. Box 20419, Humewood, Port Elizabeth, 6013 South Africa, and Department of Zoology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 3Far Horizons Wine Estate, Windmeul, 7630 South Africa 4Elandsberg Farms, Hermon, 7308 South Africa Received 22 July 2008. Accepted 13 July 2009 The quagga project has now been in progress for over 20 years. Its aim, given conclusive molecular evidence that the quagga and the plains zebra, Equus quagga, are conspecific, is the retrieval of the pelage characteristics of the quagga by selective breeding from a selected panel of plains zebra individuals. The programme has now over 25 third generation progeny, and is starting to produce individuals with a degree of striping reduction shown by none of the original founders and which approximate the striping pattern shown by at least some of the known museum specimens of quagga. These results indicate that by the fourth generation the project should have largely succeeded in its aim, and will form the basis of a herd of individuals which can be displayed in the Western Cape as an illustration of a phenotype which had disappeared from extant populations of plains zebra. Key words: plains zebra, quagga, selective breeding. INTRODUCTION 1999). However, it needs to be borne in mind that it The quagga (Equus quagga quagga) belongs was easier for collectors to send a skin to a mu- to the mammalian order Perissodactyla, which seum than the whole animal or the skeleton. -

Keystone Biology Remediation B2: Genetics

Keystone Biology Remediation B2: Genetics Assessment Anchors: • to describe and/or predict observed patterns of inheritance (i.e. dominant, recessive, co- dominance, incomplete dominance, sex-linked, polygenic, and multiple alleles) (B.2.1.1) • to describe the processes that can alter composition or number of chromosomes (i.e. crossing-over, nondisjunction, duplication, translocation, deletion, insertion, and inversion). (B.2.1.2) • to describe how the processes of transcription and translation are similar in all organisms (B.2.2.1) • to describe the role of ribosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and the nucleus in the production of specific types of proteins (B.2.2.2) • to describe how genetic mutations alter the DNA sequence and may or may not affect phenotype (e.g. silent, nonsense, frameshift) (B.2.3.1) • to describe how genetic engineering has impacted the fields of medicine, forensics, and agriculture (e.g. selective breeding, gene splicing, cloning, genetically modified organisms, gene therapy) (B.2.4.1) Unit Vocabulary: agriculture gene splicing nondisjunction biotechnology gene therapy nonsense mutation chromosomal mutation genetic engineering phenotype cloning genetically modified organism point mutation co-dominance genetics polygenic trait crossing-over genotype protein synthesis deletion Golgi apparatus recessive inheritance dominant inheritance incomplete dominance ribosome duplication (mutation) inheritance selective breeding endoplasmic reticulum insertion sex-linked trait forensics inversion silent mutation frameshift mutation missense mutation transcription gene expression multiple alleles translation gene recombination mutation translocation Assessment Anchor: Describe and/or predict observed patterns of inheritance (i.e. dominant, recessive, co-dominance, incomplete dominance, sex- linked, polygenic, and multiple alleles) (B.2.1.1) Dominant / Recessive Description: Two alleles exist for the gene.