Open PDF 176KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 290 – DECEMBER 2018 Extract from President Roosevelt’s, “Fireside Chat to the Nation”, 29 December 1940: “….we cannot escape danger by crawling into bed and pulling the covers over our heads……if Britain should go down, all of us in the Americas would be living at the point of a gun……We must produce arms and ships with every energy and resource we can command……We must be the great arsenal of democracy”. oOoOoOoOoOoOoOo The Poppies of four years ago at the Tower of London have been replaced by a display of lights. Just one of many commemorations around the World to mark one hundred years since the end of The Great War. Another major piece of art, formed a focal point as the UK commemorated 100 years since the end of the First World War. The ‘Shrouds of the Somme’ brought home the sheer scale of human sacrifice in the battle that came to epitomize the bloodshed of the 1914-18 war – the Battle of the Somme. Artist Rob Heard hand stitched and bound calico shrouds for 72,396 figures representing British Commonwealth servicemen killed at the Somme who have no known grave, many of whose bodies were never recovered and whose names are engraved on the Thiepval Memorial. Each figure of a human form, was individually shaped, shrouded and made to a name. They were laid out shoulder to shoulder in hundreds of rows to mark the Centenary of Armistice Day at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park from 8-18th November 2018 filling an area of over 4000 square metres. -

Saltash Heritage

SALTASH HERITAGE Newsletter No. 76 April 2020 Information Because of the problem with getting the April newsletter printed and distributed Saltash Heritage have decided to make it available to everyone via public media. Saltash Heritage produces a newsletter three times a year to keep our members updated and informed. A short film of the new exhibition can be seen at:- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wikpY4ovGP8&t=11s Enjoy - and come and see us when we finally open. www.saltash-heritage.org.uk e-mail [email protected] Forthcoming events Opening of museum Saltash Heritage Delayed Saltash Heritage AGM Delayed Contents Information 2 Stewards Party 15 From the chairman 3 Secrets of the museum 18 Sylvia’s Blog 4 Public houses 18 Major Naval Ships 1914 4 Back story – Monday 19 Warships called TAMAR 5 Back story – Rabbits 21 Bryony Robins The 9 Back story – The red step 23 art of dowsing 9 Appeals 25 Road over the RAB 10 The chains of Saltash 26 Memories of WWII 11 Station valance 28 Voices in the night 14 Make your own roof cat 30 Some of our helpers 32 www.saltash-heritage.org.uk e-mail [email protected] Editorial The April newsletter is usually the easiest to fill. The new exhibition has opened with lots of photographic opportunities of guests and visitors to fill the pages. Hopefully this will happen in time for the next newsletter. When we do open there will be lots of catching up to do. As I put this newsletter together I have no idea how we will distribute it. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Tactical Notes, However Circumstances Member at Large: Have Put That Off Till Next Month

January 2010 TTaacticcticaall NNoteotess The Changing of the Guard Next Meeting: Thursday, January 20th, 2011 7 p.m. Execution of deposed club officers. WWW.MMCL.ORG THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MILITARY MODELERS CLUB OF LOUISVILLE To contact MMCL: Editor’s Note 1 President: Dr. Stu “Mr. Chicken” Cox Hopefully, you attended our December meeting Email: [email protected] and Christmas Dinner. I think we had the larges attendance we’ve ever had at one of these. The Vice President: meeing saw much good modeling comraderie as Terry “The Man Behind the Throne” well as the election of new club officers. You can Hill see our new officers listed in the box at the left. Email:[email protected] You will notice some new members of the officer ranks as well as some officers who have changed Secretary: offices. David Knights Email: [email protected] I had intended to have a completely revamped look to Tactical Notes, however circumstances Member at Large: have put that off till next month. Speaking of Noel “Porche” Walker put off, the Yellow Wings smackdown has been Email: [email protected] pushed back to March due to some unforseen scheduling difficulties. (My daughter had her Treasurer: cleft palette surgery on Jan. 18th which prevents Alex “Madoff ” Restrepo me from attending the meeting this month.) Email: [email protected]. Thanks go out to Dennis Sparks whose article Webmangler: takes up the majority of this issue. It is a good Pete “The ghost” Gay & article and I hope folks draw inspiration from it. Mike “Danger Boy” Nofsinger Email: [email protected] “Tactical Notes” is the Newsletter of the Military Modelers Club of Louisville, Inc. -

Defence Acquisition

Defence acquisition Alex Wild and Elizabeth Oakes 17th May 2016 He efficient procurement of defence equipment has long been a challenge for British governments. It is an extremely complex process that is yet to be mastered with vast T sums of money invariably at stake – procurement and support of military equipment consumes around 40 per cent of annual defence cash expenditure1. In 2013-14 Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) spent £13.9bn buying and supporting military equipment2. With the House of Commons set to vote on the “Main Gate” decision to replace Trident in 2016, the government is set to embark on what will probably be the last major acquisition programme in the current round of the Royal Navy’s post-Cold War modernisation strategy. It’s crucial that the errors of the past are not repeated. Introduction There has been no shortage of reports from the likes of the National Audit Office and the Public Accounts Committee on the subject of defence acquisition. By 2010 a £38bn gap had opened up between the equipment programme and the defence budget. £1.5bn was being lost annually due to poor skills and management, the failure to make strategic investment decisions due to blurred roles and accountabilities and delays to projects3. In 2008, the then Secretary of State for Defence, John Hutton, commissioned Bernard Gray to produce a review of defence acquisition. The findings were published in October 2009. The following criticisms of the procurement process were made4: 1 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 2 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 3 https://www.nao.org.uk/report/reforming-defence-acquisition-2015/ 4 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120913104443/http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/78821960-14A0-429E- A90A-FA2A8C292C84/0/ReviewAcquisitionGrayreport.pdf 1 [email protected] Too many types of equipment are ordered for too large a range of tasks at too high a specification. -

Uk F-35B Srvl

8.)%659/ ,QIRUPDWLRQDW 'HF 23DJHVKDYHEHHQUHSULQWHGWRUHGXFHILOH VL]HWRXSORDGWRWKLVIRUXPPDNLQJWKHWH[W 85/VµGHDG¶KRZHYHUWKH85/WH[WUHPDLQV BRIEFING: SHIPBORNE have shown that the F-35B has a Sea State 6) requirement saw ROLLING VERTICAL LANDING critical vulnerability to deck mo- it ruled out on grounds of pilot tion for the SRVL manoeuvre. So workload and risk. So a stabi- [SRVL] c.2008 Richard Scott ZKLOHWKHUHLVFRQ¿GHQFHWKDW lised VLA quickly emerged as a SRVLs can he performed safely sine qua non. [SEA STATE 6: “4 to “...Landing aids in benign conditions with good 6 metres wave height - Very rough & With SRVL now likely to he used visibility, it was apparent that Surface Wind speed from Table can be as a primary recovery technique the real task drivers for the from 27-33 knots” Sea State Table: on board CVF, there is an addi- manoeuvre were higher sea http://www.syqwestinc.com/sup- tional requirement to augment states and night/poor weath- port/Sea%20State%20Table.htm the baseline landing aids suite er conditions.” & http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ with a landing aid appropriate to 6LPXODWRUÀ\LQJXQGHUWDNHQ Sea_state ] the SRVL approach manoeuvre. on both sides of the Atlantic, in- Existing systems were evalu- To this end QinetiQ has been cluding work at BAE Systems’ ated, including the US Navy’s contracted to research, concep- Warton Motion Dome Simulator Improved Fresnel Lens Optical tualise and prototype a new VLA in December 2007, had brought Landing System (IFOLS). “How- concept, known as the Bedford the problem into sharp relief. ever, the verdict on IFOLS was Array, which takes inputs “Quite simply, these simulations that it was reasonably expensive, from inertial references to showed that pilots would crash in not night-vision goggle compat- stabilise against deck mo- high sea state conditions without ible and, as a mechanical system, tions (pitch and heave). -

The Seven Seas Tattler Issue 4.9 – February 2021

The Seven Seas Tattler Issue 4.9 – February 2021 Hello fellow members and welcome to another edition of the Tattler. We trust that you are all looking after yourselves during these difficult times and we all fervently hope that there will be a return to normality in the near future! As always, any feedback is welcome ([email protected]) Tattler - Always great to hear from our members. We received this from Rhoda Moore and Ken Baker. “Dear Jonathan "Good day Jonathan, Once again, you have provided a newsletter full of Pardon me if I appear brazen to notify Tattler that my interesting information and I always look forward to February birthday see’s my 90th celebration – the big reading your “Tattler” issues. 9zero, Wow!! I value your efforts in putting these together especially Yours aye since I have avoided any club attendance due to Covid Ken Baker Lt Cdr (rtd)" because I am at my most vulnerable age. By receiving your newsletters and the wonderful bits of information keeps me involved with Club issues. The column on Pirates was especially interesting and I OS Baker 72 years ago hope that similar historical editorial will continue in the (posing) before joining SAS future. Rand to parade through City of Johannesburg. Wishing you an enjoyable and peaceful Christmas period and every good wish to you and yours for the coming “Those were the days …..Ken year! Kind wishes Tattler - Not brazen at all Ken, but even if it were, you Rhoda” have earned that right in our book! "May calm seas and bright sunshine define the rest of your voyage". -

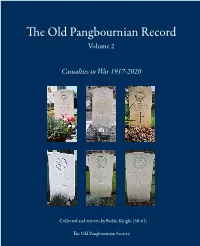

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Dyndal, Gjert Lage (2009) Land Based Air Power Or Aircraft Carriers? the British Debate About Maritime Air Power in the 1960S

Dyndal, Gjert Lage (2009) Land based air power or aircraft carriers? The British debate about maritime air power in the 1960s. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1058/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Land Based Air Power or Aircraft Carriers? The British debate about Maritime Air Power in the 1960s Gjert Lage Dyndal Doctor of Philosophy dissertation 2009 University of Glasgow Department for History Supervisors: Professor Evan Mawdsley and Dr. Simon Ball 2 Abstract Numerous studies, books, and articles have been written on Britains retreat from its former empire in the 1960s. Journalists wrote about it at the time, many people who were involved wrote about it in the immediate years that followed, and historians have tried to put it all together. The issues of foreign policy at the strategic level and the military operations that took place in this period have been especially well covered. However, the question of military strategic alternatives in this important era of British foreign policy has been less studied. -

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg (Minor editing by Alastair Donald) In preparing this Record I have consulted, wherever possible, the original reports, Battalion War and other Diaries, accounts in Globe and Laurel, etc. The War Office Official Accounts, where extant, the London Gazettes, and Orders in Council have been taken as the basis of events recounted, and I have made free use of the standard histories, eg History of the British Army (Fortescue), History of the Navy (Laird Clowes), Britain's Sea Soldiers (Field), etc. Also the Lives of Admirals and Generals bearing on the campaigns. The authorities consulted have been quoted for each campaign, in order that those desirous of making a fuller study can do so. I have made no pretence of writing a history or making comments, but I have tried to place on record all facts which can show the development of the Corps through the Nineteenth and early part of the Twentieth Centuries. H E BLUMBERG Devonport January, 1934 1 P A R T I 1837 – 1839 The Long Peace On 20 June, 1837, Her Majesty Queen Victoria ascended the Throne and commenced the long reign which was to bring such glory and honour to England, but the year found the fortunes of the Corps at a very low ebb. The numbers voted were 9007, but the RM Artillery had officially ceased to exist - a School of Laboratory and nominally two companies quartered at Fort Cumberland as part of the Portsmouth Division only being maintained. The Portsmouth Division were still in the old inadequate Clarence Barracks in the High Street; Plymouth and Chatham were in their present barracks, which had not then been enlarged to their present size, and Woolwich were in the western part of the Royal Artillery Barracks. -

Integrated Review: the Defence Tilt to the Indo-Pacific

BRIEFING PAPER Number 09217, 11 May 2021 Integrated Review: The defence tilt to the Indo- By Louisa Brooke-Holland Pacific In March 2021 the Government set out its security, defence, development and “Defence is an foreign policy and its vision of the UK’s role in the world over the next two essential part of the decades by publishing: Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated UK’s integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy and the offer to the command paper Defence in a Competitive Age. region.” These documents describe a “tilt to the Indo-Pacific.” A clear signal of this new Defence in a intent, and the Government’s commitment to “Global Britain”, is the first Competitive Age, deployment of the HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier strike group to the 22 March 2021 Indo-Pacific in 2021. This paper explores what this means for UK defence, explains the current UK defence presence in the Indo-Pacific and discusses some of the concerns raised about the tilt. It is one of a series that the Commons Library is publishing on the Integrated Review (hereafter the review) and the command paper. 1. Why tilt to the Indo-Pacific? The Government says the UK needs to engage with the Indo-Pacific more deeply for its own security. The review describes the region as being at the “centre of intensifying geopolitical competition with multiple potential flashpoints.” These flashpoints include unresolved territorial disputes in the South China Sea and East China Sea, nuclear proliferation, climate change as a potential driver of conflict, and threats from terrorism and serious organised crime.