Constantinople Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Enargeia of Music in Theory and Practice Although in Aristotle's

CHAPTER SIXTEEN THE ENARGEIA OF MUSIC IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Although in Aristotle’s Poetics music is not considered a mimetic art, musical rhetoric also makes use of the enargeia of representation, albeit not primarily under this label. The German humanist Joachim Burmeis- ter (1566–1629) defines the terminological equivalent hypotyposis in his Musica Poetica (1606) as follows: Hypotyposis est illud ornamentum, quô textus significatio ita deumbratur, ut ea, quæ textui subsunt & animam vitamq; non habent, vita esse prædita, videantur. Hoc ornamentum usitatißimum est apud authenticos Artifices. Vti- nam eâdem dexteritate ab omnibus adhiberetur Componistis.1 Hypotyposis is that ornament through which the meaning of a (song) text is elucidated in such a way that the basic words, which have no soul and no life, seem to become filled with life. This ornament is commonly used by authentic artists. If only it were skillfully applied by all composers! For Burmeister therefore hypotyposis is an important figure for giving a song text a sensory presence. As an example he cites a composition by Orlando di Lasso: “Benedicam Domino [. .]”, and in doing so claims that pathopoeia is particularly suited to producing affects: “Pathopoeia [. .] est figura apta ad affectus creandos.”2 Other music theorists of the time do 1 Joachim Burmeister, Musica Poetica: Definitionibus et divisionibus breviter delineata. Rostochii Excudebat Stephanus Myliander, Anno M.DC.VI. Facsimile ed. with introd. by Ph. Kallenberger. Laaber: Laaber-Verlag, 22007, p. 62.—Dietrich Bartel, Musica Poetica: Musical-Rhetorical Figures in German Baroque Music. Lincoln / London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p. 307 makes on this figure the following comment: “The hypotyposis is given the same task in music as in rhetoric: to vividly and realistically illustrate a thought or image found in the text. -

Nocturno 12:00:00A 04:26 Misa

SÁBADO 23 DE AGOSTO DE 2014 12:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 23 de agosto de 2014 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00a 04:26 Misa "In illo tempore" a 6 (1610) Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Los 16 12:28:26a 21:29 Entsetze dich, natur Johann Rosenmüller (1654-1682) Konrad Junghänel Concerto Palatino 12:49:55a 05:54 Te ame un gran tiempo Stefano Landi (ca1586-1639) Christina Pluhar Ensamble "L'Arpeggiata" Marco Beasley-tenor 12:55:49a 00:50 Identificación estación 01:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 23 de agosto de 2014 1AM NO - Nocturno 01:00:00a 03:38 Ricercar del 1er. tono del Zazzerino Jacopo Peri (1561-1633) Andrew Lawrence King, arpa doble 01:03:38a 04:54 La despedida Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Philippe Herreweghe Ensamble música Oblicua Birgit Remmert-soprano 01:32:32a 22:14 Sinfonietta Leos Janacek (1854-1928) Frantisek Jilek Filarmónica del Estado de Brno 01:54:46a 00:50 Identificación estación 02:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 23 de agosto de 2014 2AM NO - Nocturno 02:00:00a 23:13 La flecha del elfo op.30 Niels Wilhelm Gade (1817-1890) Dimiti Kitajenko Coro y Sinf. Radio nacional Danesa Eva Johansson-sop./Anne Gjevang-alto./Poul Elming-ten. 02:47:13a 10:48 Aria "¡Pueblos de Tesalia!..." K.316/300b Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756- Franz Brüggen Del siglo XVIII Cyndia Seiden-soprano 02:58:01a 00:50 Identificación estación 03:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 23 de agosto de 2014 3AM NO - Nocturno 03:00:00a 17:48 Motete alemán Op.62 Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Stefan Parkman Coro Radio nal. -

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

International Journal of Education Humanities and Social Science

International Journal of Education Humanities and Social Science ISSN: 2582-0745 Vol. 2, No. 04; 2019 EARLY MELODRAMA, EARLY TRAGICOMIC Roberto Gigliucci Sapienza University of Rome Piazzale (Square) Aldo Moro, 5, Rome 00185, Italy [email protected] ABSTRACT This essay tries to demonstrate that the tragicomic blend, typical of Baroque Melodrama, has born much earlier than what is commonly believed. Just in the Jesuitical play “Eumelio” (1606) the hellish characters are definitely comical; a year later, in the celebrated “Orfeo” by Striggio jr. and Monteverdi, we think to find droll, if not grotesque, elements. The article ends considering the opera “La morte d’Orfeo” by S. Landi (1619), particularly focusing on the character of Charon. Key Words: Tragicomic, Melodrama, Orpheus’ myth. INTRODUCTION An excellent scholar as Gloria Staffieri, in a recent historical frame of Melodrama from its birth up to Metastasio, reaffirms a widespread statement: the “invention” of tragicomic blend in the Opera is due to Rospigliosi, during the Barberini age [1], starting from 1629 (Sant’Alessio) and developing increasingly during the Thirties [2]. A quite late birth, therefore, of the tragicomic element, which is universally considered one of the most identitarian – strongly peculiar – feature of Baroque Melodrama [3]. In our short speech, we would demonstrate that this fundamental trait of Operatic mood was born at the very inception of the genre itself. Rinuccini If we skip now the case of Dafne [4] (where Rinuccini puts himself in line with the experiment of satira scenica by Giraldi Cinzio, the Egle [5], with its sad metamorphic ending), we may consider Euridice as a happy ending tragedy. -

Martha Jane Gilreath Submi Tted As an Honors Paper in the Iartment Of

A STTJDY IN SEV CENT1 CHESTRATIO>T by Martha Jane Gilreath SubMi tted as an Honors Paper in the iartment of Jiusic Voman's College of the University of Xorth Carolina Greensboro 1959 Approved hv *tu£*l Direfctor Examining Committee AC! ' IKTS Tt would be difficult to mention all those who have in some way helped me with this thesis. To mention only a few, the following have mv sincere crratitude: Dr. Franklyn D. Parker and members of the Honors -fork Com- mittee for allowing me to pursue this study; Dr. May ". Sh, Dr. Amy Charles, Miss Dorothy Davis, Mr. Frank Starbuck, Dr. Robert Morris, and Mr, Robert Watson for reading and correcting the manuscript; the librarians at Woman's College and the Music Library of the University of North Carolina through whom I have obtained many valuable scores; Miss Joan Moser for continual kindness and help in my work at the Library of the University of North Carolina; mv family for its interest in and financial support of my project; and above all, my adviser, Miss Elizabeth Cowlinr, for her invaluable assistance and extraordinary talent for inspiring one to higher scholastic achievenent. TAm.E OF COKTB 1 1 Chapter I THfcl 51 NTURY — A BACKGROUND 3 Chapter II FIRST RUB OR( 13 Zhapter III TT*rn: fTIONS IN I] 'ION BY COMPOSERS OF THE EARLY SEVE TORY 17 Introduction of nasso Continuo 17 thods of Orchestration 18 Duplication of Instruments 24 Pro.gramatic I'ses of Scoring .25 id Alternation between Instruments. .30 Introduction of Various Instrumental devices 32 Dynamic Contrasts 32 Rowing Methods 33 Pizzicato -

39 39 Basler Beiträge Zur Historischen Musikpraxis

BASLER BEITRÄGE ZUR HISTORISCHEN MUSIKPRAXIS 39 BASLER BEITRÄGE Herausgegeben von Thomas Drescher ZUR HISTORISCHEN und Martin Kirnbauer MUSIKPRAXIS BASLER BEITRÄGE BEITRÄGE BASLER HISTORISCHEN ZUR MUSIKPRAXIS Groß Geigen um 1500 Orazio Michi und die Harfe um 1600 Der Band versammelt Forschungsbeiträge zur nordalpinen Groß Geige um 1500 und zur Harfe in Rom um 1600. Sie entstanden im Rahmen des SNF-Forschungsprojekts « Groß Geigen, Vyolen, Rybeben – nordalpine Streichinstrumente um 1500 und ihre Praxis » und aus Vorträgen am Studientag « Orazio Michi dell’Arpa », der im April 2015 an der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis stattfand. Beide Projekte verbindet die Herange- hensweise an ihren Gegenstand : Um zu neuen Erkenntnissen zu gelangen, wurden Instrument, Repertoire und Spielweise praktisch erprobt und auch nicht-musikalische Quellen ausgewertet. Die Herausgeberin Martina Papiro studierte Kunst- und Musikwissenschaft in Basel, Berlin und Florenz. Seit 2016 ist sie wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin der Schola Canto- rum Basiliensis / FHNW. Sie promovierte über die Bilddrucke der Florentiner Festkul- tur ; ihr Forschungsinteresse gilt dem Zusammen spiel der Künste. Die Basler Beiträge zur Historischen Musikpraxis setzen das seit 1977 erscheinende Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis fort. Die von der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis / 1500 Geigen um Groß 1600 um die Harfe und Orazio Michi FHNW herausgegebenen Beiträge dokumentieren die wissenschaftliche Auseinander- setzung mit allen Bereichen der Historischen Musikpraxis. Jeder Band präsentiert MARTINA PAPIRO (HG.) Themenschwerpunkte aus Tagungen der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, ergänzt durch freie Beiträge. 39 Groß Geigen um 1500 Orazio Michi und die Harfe um 1600 www.schwabeverlag.ch ® MIX Papier aus verantwor- tungsvollen Quellen ® www.fsc.org FSC C083411 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. -

Cremona Baroque Music 2018

Musicology and Cultural Heritage Department Pavia University Cremona Baroque Music 2018 18th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music A Programme and Abstracts of Papers Read at the 18th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music Crossing Borders: Music, Musicians and Instruments 1550–1750 10–15 July 2018 Palazzo Trecchi, Cremona Teatro Bibiena, Mantua B Crossing Borders: Music, Musicians and Instruments And here you all are from thirty-one countries, one of Welcome to Cremona, the city of Monteverdi, Amati and the largest crowds in the whole history of the Biennial Stradivari. Welcome with your own identity, to share your International Conference on Baroque Music! knowledge on all the aspects of Baroque music. And as we More then ever borders are the talk of the day. When we do this, let’s remember that crossing borders is the very left Canterbury in 2016, the United Kingdom had just voted essence of every cultural transformation. for Brexit. Since then Europe—including Italy— has been It has been an honour to serve as chair of this international challenged by migration, attempting to mediate between community. My warmest gratitude to all those, including humanitarian efforts and economic interests. Nationalist the Programme Committee, who have contributed time, and populist slogans reverberate across Europe, advocating money and energy to make this conference run so smoothly. barriers and separation as a possible panacea to socio- Enjoy the scholarly debate, the fantastic concerts and political issues. Nevertheless, we still want to call ourselves excursions. Enjoy the monuments, the food and wine. European, as well as Italian, German, French, Spanish, And above all, Enjoy the people! English etc. -

Various the Age of Humanism (1540-1630) (Volume IV of the History of Music in Sound) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various The Age Of Humanism (1540-1630) (Volume IV Of The History Of Music In Sound) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: The Age Of Humanism (1540-1630) (Volume IV Of The History Of Music In Sound) Country: UK Style: Renaissance MP3 version RAR size: 1892 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1651 mb WMA version RAR size: 1820 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 632 Other Formats: ADX DTS MP1 RA FLAC AUD AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Capriccio Sopra Un Soggetto A Band 1 –Girolamo Frescobaldi Harpsichord – Thurston Dart Ricercar Arioso No. I A Band 2 –Andrea Gabrieli Organ – Suzi Jeans Ach Gott, Vom Himmel Sieh' Darein A Band 3 –Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck Organ – Suzi Jeans Orfeo, Act IV A Band 4 –Claudio Monteverdi Conductor – Jack Allan Westrup A Band 5 –Stefano Landi Bevi, Bevi Companies, etc. Published By – E.M.I. Records Limited Credits Edited By – J. A. Westrup Edited By [General Editor, Series] – Gerald Abraham Related Music albums to The Age Of Humanism (1540-1630) (Volume IV Of The History Of Music In Sound) by Various 1. All Saved Freak Band - Harps on Willows Best of the All Saved Freak Band Volume One 2. Various - The History Of Jazz, Volume Four: Enter The Cool 3. Gap Band, The - Gap Band V - Jammin' 4. Fifth Avenue Dance Band, Allan Selby & his Band - You're Always In My Arms / Rio Rita 5. Girolamo Frescobaldi, Ferruccio Vignanelli - Classical Favourites 6. Ferko String Band - The Best Of Ferko String Band 7. Giovanni Gabrieli / Girolamo Frescobaldi / Giovanni Trabaci / Bernardo Pasquini / Domenico Zippoli Organo E. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 03:30:09PM Via Free Access 96 Chapter Two

chapter two MAFFEO BARBERINI—URBAN VIII, THE POET-POPE, OR: THE POWER OF POETIC PROPAGANDA Introduction In the early years of the pontificate of Paul V (1605–1621), an anony- mous avvisatore assembled a series of short biographies outlining the characters and characteristics of the various cardinals who would take part in the conclave if the Pope were to die. About Maffeo Barberini he wrote, after a brief sketch of his career: ‘he is a man of great talent, well versed in Italian letters, in Latin and in Greek; though more assiduous than brilliant, he is of an honourable nature, without any baseness’, which was praise indeed in view of the judgement he passed on some other eminent candidates. It also shows that, already as a cardinal, Bar- berini was known as a writer, a poet.1 Some twenty years later, when Maffeo had become Urban, the well- known literato Fulvio Testi described to a friend an evening he had spent with the Pope. Apologizing to Urban for not having written any poetry recently due to his increased work load, Testi was gently reprimanded when the Pope remarked: ‘We, too, have some business to attend to, but nevertheless for Our recreation sometimes We compose a poem’. Urban went on to tell that he had lately written some Latin poems and would like Testi to read them. ‘And hence, retreating into the next room where he sleeps, he fetched some sheets and started to read to me an ode written after the manner of Horace, which really was very beautiful. I have lauded it and praised it to the stars because certainly as to Latin compositions the Pope has few or none who equal him.’2 1 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (BAV), Manoscritti Boncompagni-Ludovisi,Vol.C20,f.167v: “è signore d’ingegno grande, di belle lettere vulgari, latine e greche, e piutosto asseg- nato che splendido, ma honorato, senza sordidezza”. -

The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family In

The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family (Rome, 1632-1643) Virginia Christy Lamothe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Tim Carter, chair Annegret Fauser Anne MacNeil John Nádas Jocelyn Neal © 2009 Virginia Christy Lamothe ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Virginia Christy Lamothe: “The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family (Rome, 1632-1643)” (Under the direction of Tim Carter) In a time of religious war, plague, and reformation, Pope Urban VIII and his cardinal- nephews Antonio and Francesco Barberini sought to establish the authority of the Catholic Church by inspiring audiences of Rome with visions of the heroic deeds of saints. One way in which they did this was by commissioning operas based on the lives of saints from the poet Giulio Rospigliosi (later Pope Clement IX), and papal musicians Stefano Landi and Virgilio Mazzocchi. Aside from the merit of providing an in-depth look at four of these little-known works, Sant’Alessio (1632, 1634), Santi Didimo e Teodora (1635), San Bonifatio (1638), and Sant’Eustachio (1643), this dissertation also discusses how these operas reveal changing ideas of faith, civic pride, death and salvation, education, and the role of women during the first half of the seventeenth century. The analysis of the music and the drama stems from studies of the surviving manuscript scores, libretti, payment records and letters about the first performances. -

STEFANO LANDI's ARIE a UNA VOCE and EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN GUITAR MUSIC with ALFABETO NOTATION by NICHOLAS ALEXANDE

STEFANO LANDI’S ARIE A UNA VOCE AND EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN GUITAR MUSIC WITH ALFABETO NOTATION by NICHOLAS ALEXANDER GALFOND B.M. University of Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Scott Warfield © 2015 Nicholas Galfond ii ABSTRACT In the first few decades of the seventeenth century countless songbooks were published in Italy, more than 300 of which included the notation system for guitar accompaniment known as alfabeto. This early repertoire for the five-course Spanish guitar was printed mostly in Naples, Rome, and Florence, and was a pivotal precursor to our modern tonal musical understanding. The very nature of both the instrument and its characteristic dance-song accompaniment style led composers to create block harmonies in diatonic progressions long before such concepts bore any semblance to a functioning theory. This paper uses the 1620 publication Arie a una voce by Roman composer Stefano Landi as a case study through which to examine the important roles that both alfabeto and the guitar played in the development of monody. The ongoing debates over the practicality, authorship, and interpretation of alfabeto notation are all addressed in reference to the six pieces marked “per la chitara Spag.” found near the end of Landi’s first songbook. This will provide an understanding of the alfabeto notation system as well as the role of the guitar in the rise of monody, provide more specific answers concerning the viability of accompanying these specific songs on the guitar, and provide a means for constructing an informed interpretation and recording of these examples of a long-overlooked repertoire. -

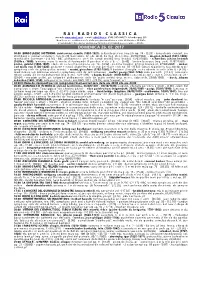

R a I R a D I O 5 C L a S S I C a Domenica 26. 02. 2017

RAI RADIO5 CLASSICA sito web: www.radio5.rai.it e-mail: [email protected] SMS: 347 0142371 televideo pag. 539 Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto DOMENICA 26. 02. 2017 00:00 EUROCLASSIC NOTTURNO: saint-saëns, camille (1835-1921): saltarello per voci masch op. 74 - [5.33] - lamentabile consort: jan stromberg e gunnar andersson, ten; bertil marcusson, br; olle sköld, bs (reg. stoccolma, 29/10/1984) - wagner, richard (1813-1883): tannhäuser: ouverture - [14.36] - BBC philharmonic orch dir. vassily sinaisky (reg. kendal, 12/02/2000) - schmelzer, johann heinrich (1620ca.-1680): lamento sopra la morte di ferdinando III per due vl vla e b. c. - [6.45] - london baroque (reg. york, 11/07/1998) - pierné, gabriel (1863-1937): étude de concert pour piano op. 13 - [3.52] - paloma kouider, pf (reg. budapest, 07/04/2008) - weber, carl maria von (1786-1826): andante e rondò ungherese in do min per fag e orch op. 35 - [9.54] - juhani tapaninen, fag; finnish radio symphony orch dir. jukka-pekka saraste - rossini, gioachino (1792-1868): il barbiere di siviglia: ecco ridente in cielo (atto I) - [4.59] - mark dubois, ten; kitchener waterloo symphony orch dir. raffi armenian - muffat, georg (1653-1704): suite per orch - [11.37] - armonico tributo austria dir. lorenz duftschmid (reg. herne, 14/11/99) - chopin, frédéric (1810-1849): concerto per pf e orch n. 2 in fa min op. 21 - [29.04] - maurizio pollini, pf; belgrade philharmonic orch dir. zubin mehta (reg. mono, dubrovnik, 23/08/1968) - bach, johann sebastian (1685-1750): suite per vcl n.