Treasure Island the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson adapted for the stage by Stewart Skelton Stewart E. Skelton 6720 Franklin Place, #404 Copyright 1996 Hollywood, CA 90028 213.461.8189 [email protected] SETTING: AN ATTIC A PARLOR AN INN A WATERFRONT THE DECK OF A SHIP AN ISLAND A STOCKADE ON THE ISLAND CAST: VOICE OF BILLY BONES VOICE OF BLACK DOG VOICE OF MRS. HAWKINS VOICE OF CAP'N FLINT VOICE OF JIM HAWKINS VOICE OF PEW JIM HAWKINS PIRATES JOHNNY ARCHIE PEW BLACK DOG DR. LIVESEY SQUIRE TRELAWNEY LONG JOHN SILVER MORGAN SAILORS MATE CAPTAIN SMOLLETT DICK ISRAEL HANDS LOOKOUT BEN GUNN TIME: LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TREASURE ISLAND/Skelton 1 SCENE ONE (A treasure chest sits alone on plank flooring. We hear the creak of rigging on a ship set adrift. As the lights begin to dim, we hear menacing, thrilling music building in the background. When a single spot is left illuminating the chest, the music comes to a crashing climax and quickly subsides to continue playing in the background. With the musical climax, the lid of the chest opens with a horrifying groan. Light starts to emanate from the chest, and the spotlight dims. Voices and the sounds of action begin to issue forth from the chest. The music continues underneath.) VOICE OF BILLY BONES (singing) "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum! Drink and the devil had done for the rest - Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!" VOICE OF BLACK DOG Bill! Come, Bill, you know me; you know an old shipmate, Bill, surely. -

Treasure Island

School Radio Treasure Island 6. The stockade and the pirates attack Narrator: On Treasure Island you might be forgiven for thinking a war was taking place. Anchored in the bay, the Hispaniola is firing her cannon deep into the woods. And through the trees, the pirates advance, muskets blazing. Oblivious to the danger, young Jim Hawkins races through the undergrowth heading for the Union Jack that flies bravely atop the trees. When he gets there, it’s a relief to find there’s shelter. A tall wooden stockade stands in a clearing - and inside it, his old friends Squire Trelawney, Doctor Livesey, Captain Smollett and a handful of faithful sailors, are fending off a full-blown attack from the pirates. Jim: Doctor! Squire! Captain! Let down the drawbridge! It’s me! Dr Livesey: Quickly, men, let the boy in! Squire: Jim - we thought we’d lost you! Hunter: Happen as still might unless we keep them muskets firing. Squire: Ah, yes, good thinking my man. Repel the blackguards! A sovereign for every man we put down! Narrator: But the pirates give up the fight - for now. Jim and the others exchange news. It turns out that the stockade they’re in was built many years ago by Captain Flint as a stronghold if ever he should be attacked. Squire Trelawney and the others just beat Silver and the pirates to it - though they lost a couple of good men in so doing. They managed to salvage enough guns, ammunition and food from the ship to keep them going for a couple of weeks but not much more. -

Treasure Island

UNIT: TREASURE ISLAND ANCHOR TEXT UNIT FOCUS Students read a combination of literary and informational texts to answer the questions: What are different types of treasure? Who hunts for treasure and how? Why do people Great Illustrated Classics Treasure Island, Robert Louis search for treasure? Students also discuss their personal treasures. Students work to Stevenson understand what people are willing to do to get treasure and how different types of treasure have been found, lost, cursed, and stolen over time. RELATED TEXTS Text Use: Describe characters’ changing motivations in a story, read and apply nonfiction Literary Texts (Fiction) research to fictional stories, identify connections of ideas or events in a text • The Ballad of the Pirate Queens, Jane Yolen Reading: RL.3.1, RL.3.2, RL.3.3, RL.3.4, RL.3.5, RL.3.6, RL.3.7, RL.3.10, RI.3.1, RI.3.2, RI.3.3, • “The Curse of King Tut,” Spencer Kayden RI.3.4, RI.3.5, RI.3.6, RI.3.7, RI.3.8, RI.3.9, RI.3.10 • The Stolen Smile, J. Patrick Lewis Reading Foundational Skills: RF.3.3d, RF.3.4a-c • The Mona Lisa Caper, Rick Jacobson Writing: W.3.1a-d, W.3.2a-d, W.3.3a-d, W.3.4, W.3.5, W.3.7, W.3.8, W.3.10 Speaking and Listening: SL.3.1a-d, SL.3.2, SL.3.3, SL.3.4, SL.3.5, SL.3.6 Informational Texts (Nonfiction) • “Pirate Treasure!” from Magic Tree House Fact Language: L.3.1a-i; L.3.2a, c-g; L.3.3a-b; L.3.4a-b, d; L.3.5a-c; L.3.6 Tracker: Pirates, Will Osborne and Mary Pope CONTENTS Osborne • Finding the Titanic, Robert Ballard Page 155: Text Set and Unit Focus • “Missing Mona” from Scholastic • -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

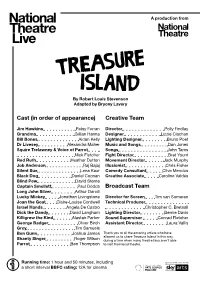

Cast (In Order of Appearance) Creative Team

A production from By Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery Cast (in order of appearance) Creative Team Jim Hawkins Patsy Ferran Director Polly Findlay Grandma Gillian Hanna Designer Lizzie Clachan Bill Bones Aidan Kelly Lighting Designer Bruno Poet Dr Livesey Alexandra Maher Music and Songs Dan Jones Squire Trelawney & Voice of Parrot Songs John Tams Nick Fletcher Fight Director Bret Yount Red Ruth Heather Dutton Movement Director Jack Murphy Job Anderson Raj Bajaj Illusionist Chris Fisher Silent Sue Lena Kaur Comedy Consultant Clive Mendus Black Dog Daniel Coonan Creative Associate Caroline Valdés Blind Pew David Sterne Captain Smollett Paul Dodds Broadcast Team Long John Silver Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey Jonathan Livingstone Director for Screen Tim van Someren Joan the Goat Claire-Louise Cordwell Technical Producer Israel Hands Angela De Castro Christopher C. Bretnall Dick the Dandy David Langham Lighting Director Bernie Davis Killigrew the Kind Alastair Parker Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher George Badger Oliver Birch Assistant Director Laura Vallis Grey Tim Samuels Ben Gunn Joshua James Thank you to all the amazing artists who have allowed us to share Treasure Island in this way, Shanty Singer Roger Wilson during a time when many theatre fans aren’t able Parrot Ben Thompson to visit their local theatre. Running time: 1 hour and 50 minutes, including a short interval BBFC rating: 12A for cinema Help Jim Hawkins find the buried gold! Can you trace your way from the ship to X marks the spot and the treasure? Image: Freepik.com Image: Did you know? Excerpts from Treasure Island show programme articles by Andrew Lambert, David Cordingly and Tristan Gooley. -

TREASURE ISLAND SQUIRE TRELAWNEY, Dr. Livesey, and the Rest of These Gentlemen Having Asked Me to Write Down the Whole Particula

A Ria Press Edition of Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Page 1 of 53. TREASURE ISLAND call me? You mought call me captain. Oh, I see what you’re at— there”; and he threw down three or four gold pieces on the by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1883 threshold. “You can tell me when I’ve worked through that,” Ria Press says he, looking as fierce as a commander. To S.L.O., an American gentleman in accordance with whose And indeed bad as his clothes were and coarsely as he spoke, classic taste the following narrative has been designed, it is now, he had none of the appearance of a man who sailed before the in return for numerous delightful hours, and with the kindest mast, but seemed like a mate or skipper accustomed to be obeyed wishes, dedicated by his affectionate friend, the author. or to strike. The man who came with the barrow told us the mail TO THE HESITATING PURCHASER had set him down the morning before at the Royal George, that If sailor tales to sailor tunes, he had inquired what inns there were along the coast, and hearing Storm and adventure, heat and cold, ours well spoken of, I suppose, and described as lonely, had cho- If schooners, islands, and maroons, sen it from the others for his place of residence. And that was all And buccaneers, and buried gold, we could learn of our guest. And all the old romance, retold He was a very silent man by custom. All day he hung round Exactly in the ancient way, Can please, as me they pleased of old, the cove or upon the cliffs with a brass telescope; all evening he The wiser youngsters of today: sat in a corner of the parlour next the fire and drank rum and wa- —So be it, and fall on! If not, ter very strong. -

Odds on Treasure Island William H

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 5 1996 Odds on Treasure Island William H. Hardesty III. David D. Mann Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hardesty, William H. III. and Mann, David D. (1996) "Odds on Treasure Island," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol29/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William H Hardesty, III David D. Mann Odds on Treasure Island Knowledge of a writer's life can often help readers glimpse how that writer crafted fictional worlds. Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island (1883) is a case in point. 1 Because Treasure Island is an imaginative work of fiction specifically designed for younger readers, contemporary audiences seldom see the relevance of Stevenson's life to the novel they read. Yet an examination of what Stevenson was doing in 1881, when he wrote the original narrative, provides us with some understanding of how it was written and why Stevenson used certain fictive elements in the fabric of the nove1. 2 Knowing that Stevenson wrote part of the novel in Scotland and part in Switzerland-with a long interruption between the efforts-forces us to consider the differences between these two parts. Stevenson began the novel in late August 1881, basing the setting on a map he had drawn to entertain his stepson (Samuel) Lloyd Osbourne (the S. -

9Th Grade Summer Reading 2020

SUMMER 2020 SUMMER READING 9th Grade Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Ninth grade students are required to read Treasure Island, and they should be prepared to take a written test on it during the first week of school. SEE ATTACHED PAGES FOR MORE INFORMATION. Study Guide for Treasure Island 9th Grade English As you read Treasure Island this summer, you should pay attention to four main areas: characters, plot, setting and vocabulary. The following study guide will help as you read the book and study for the test. However, this guide does NOT cover every question on the test. Read for comprehension, and enjoy reading Treasure Island. The test will be given during the first week of school. Characters: Describe each character. How did each character help to advance the plot? ✴ Jim Hawkins - ✴ Mrs. Hawkins - ✴ Squire Trelawney - ✴ Billy Bones - ✴ Long John Silver - ✴ Captain Smollett - ✴ Dr. Livesey - ✴ Israel Hands – ✴ Black Dog - ✴ Alan - ✴ Ben Gunn - ✴ Mr. Arrow - ✴ Capt’n Flint - ✴ Tom Redruth - ✴ Abraham Gray - Setting: Describe the following places found in the book: ✴ “Admiral Benbow” - ✴ Bristol - ✴ The Hispaniola – ✴ Setting ✴ Stockade - ✴ Treasure Island - ✴ Cape of the Woods - ✴ Spy-Glass - Plot: Short answer questions concerning the plot of the story: ✴ Why does Billy Bones pay Jim? ✴ Why did Jim and his mother search for the sea-chest? ✴ Who did Jim see at the Inn? ✴ Who bought and outfitted the Hispaniola? ✴ What was Silver’s job on the Hispaniola? ✴ How did Jim discover Silver’s plan? ✴ When did Captain Smollett realize -

Treasure Island the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Treasure Island The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: J. Todd Adams (left) as Ben Gunn and Sceri Sioux Ivers as Jim Hawkins in the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s 2017 production of Treasure Island. Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersTreasure Island 5 Playwrights 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play A Recipe for Gleeful Romance 9 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Treasure Island Mrs. Hawkins runs the Admiral Benbow Inn where Captain Billy Bones comes to stay, hiding from a “seafarin’ man with one leg.” The townspeople flock to hear his stories, though Dr. -

The Poetics of Talk in Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship Fall 2014 The Poetics of Talk in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island Amy Wong University of California, Los Angeles, [email protected] https://doi.org/10.1353/sel.2014.0048 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wong, Amy, "The Poetics of Talk in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island" (2014). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 296. https://doi.org/10.1353/sel.2014.0048 DOI http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/sel.2014.0048 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 “I am Not a Novelist Alone”: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Adventures in Talk In “Talk and Talkers” (1882), a two-part critical essay that first appeared in the popular monthly, Cornhill, Robert Louis Stevenson elevates the phenomenon of talk over and above any kind of literary endeavor: “Literature in many of its branches is no other than the shadow of good talk.”1 This particular statement—and his broader advocacy of talk in this essay—demonstrates that Stevenson, near the start of his career, had concluded that “good talk” presented a significant challenge to the artistic preeminence conventionally accorded to literary print. In “Talk and Talkers,” Stevenson ascribes to “good talk” an unmatchable vitality, such that “the excitement of a good talk lives for a long while after in the blood, the heart still hot within you,” while in stark contrast, “written words remain fixed, become idols even to the writer, found wooden dogmatisms” (pp. -

Long Joan Silver Long Joan Silver

LONG JOAN SILVER __________________________ A full-length comedy by Arthur M. Jolly Based on the novel Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson This script is for evaluation only. It may not be printed, photocopied or distributed digitally under any circumstances. Possession of this file does not grant the right to perform this play or any portion of it, or to use it for classroom study. www.youthplays.com [email protected] 424-703-5315 Long Joan Silver © 2013 Arthur M. Jolly All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-62088-361-7. Caution: This play is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, Canada, the British Commonwealth and all other countries of the copyright union and is subject to royalty for all performances including but not limited to professional, amateur, charity and classroom whether admission is charged or presented free of charge. Reservation of Rights: This play is the property of the author and all rights for its use are strictly reserved and must be licensed by his representative, YouthPLAYS. This prohibition of unauthorized professional and amateur stage presentations extends also to motion pictures, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video and the rights of adaptation or translation into non-English languages. Performance Licensing and Royalty Payments: Amateur and stock performance rights are administered exclusively by YouthPLAYS. No amateur, stock or educational theatre groups or individuals may perform this play without securing authorization and royalty arrangements in advance from YouthPLAYS. Required royalty fees for performing this play are available online at www.YouthPLAYS.com. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice.