Hs/S3/09/1/A Health and Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

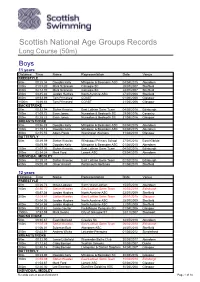

Scottish National Age Groups Records

Scottish National Age Groups Records Long Course (50m) Boys 11 years Distance Time Name Representation Date Venue FREESTYLE 50m 00:28.34 Douglas Kelly Milngavie & Bearsden ASC 04/04/2015 Aberdeen 100m 01:01.20 Mark Szaranek Carnegie SC 25/07/2007 Sheffield 200m 02:12.70 Mark Szaranek Carnegie SC 24/07/2007 Sheffield 400m 04:45.46 Jordan Hughes North Ayrshire ASC 27/07/2008 Sheffield 800m 09:53.99 Tom Primavesi COAST 01/04/2006 Glasgow 1500m 18:46.44 Tom Primavesi COAST 21/03/2006 Glasgow BACKSTROKE 50m 00:32.94 Stefan Krawiec East Lothian Swim Team 04/02/2018 Edinburgh 100m 01:09.72 Evan Jones Nuneaton & Bedworth SC 29/05/2016 Coventry 200m 02:28.22 Evan Jones Nuneaton & Bedworth SC 31/03/2016 Glasgow BREASTSTROKE 50m 00:36.28 Douglas Kelly Milngavie & Bearsden ASC 03/04/2015 Aberdeen 100m 01:19.12 Douglas Kelly Milngavie & Bearsden ASC 04/04/2015 Aberdeen 200m 02:55.55 Adam Poole Warrington Warriors 11/04/2010 Glasgow BUTTERFLY 50m 00:29.59 Stefan Krawiec Windygoul Primary School 27/01/2018 East Kilbride 00:29.95 Douglas Kelly Milngavie & Bearsden ASC 01/04/2015 Aberdeen 100m 01:07.36 Stefan Krawiec East Lothian Swim Team 04/02/2018 Edinburgh 200m 02:34.24 Mark Ford Lanark ASC 03/04/2015 Aberdeen INDIVIDUAL MEDLEY 200m 02:29.37 Stefan Krawiec East Lothian Swim Team 02/02/2018 Edinburgh 400m 05:20.39 Oliver Kincart Portsmouth Northsea 01/08/2010 Sheffield 12 years Distance Time Name Representation Date Venue FREESTYLE 50m 00:26.73 Myles Lapsley Swim West Lothian 15/07/2016 Aberdeen 100m 00:56.77 Stefan Krawiec East Lothian Swim Team 10/02/2019 -

4-12-2011 Event 1 Men, 400M Freestyle Jeugd/Senioren 02-12

Open Nederlandse Kampioenschappen Zwemmen Eindhoven, 2- - 4-12-2011 Event 1 Men, 400m Freestyle Jeugd/Senioren 02-12-2011 Results World Record 3:40.07 Paul Biedermann Rome (ITA) 26-07-2009 European Record 3:40.07 Paul Biedermann Rome (ITA) 26-07-2009 Nederlands Record Senioren 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband Amersfoort 20-04-2002 Nederlands Record Jeugd 3:55.65 Dion Dreesens Belgrado (SRB) 06-07-2011 Limiet OS 2012 Londen 3:47.90 Richttijd EK 2012 Antwerpen 3:51.49 Richttijd EJK 2012 Antwerpen 3:58.01 rank name club name time RT pts Jeugd 1 en 2 provisional results Louis Croenen ShaRK SHARK/133/94 4:00.24 +0,74 50m: 28.06 28.06 150m: 1:28.92 30.52 250m: 2:29.75 30.31 350m: 3:30.59 30.29 100m: 58.40 30.34 200m: 1:59.44 30.52 300m: 3:00.30 30.55 400m: 4:00.24 29.65 Lander Hendrickx BEST BEST/241/94 4:00.38 +0,73 50m: 28.04 28.04 150m: 1:28.85 30.61 250m: 2:29.60 30.31 350m: 3:30.64 30.46 100m: 58.24 30.20 200m: 1:59.29 30.44 300m: 3:00.18 30.58 400m: 4:00.38 29.74 Maarten Brzoskowski EIFFELswimmersPSV 199500769 4:05.97 +0,71 50m: 28.10 28.10 150m: 1:30.50 31.51 250m: 2:34.00 31.28 350m: 3:36.48 31.30 100m: 58.99 30.89 200m: 2:02.72 32.22 300m: 3:05.18 31.18 400m: 4:05.97 29.49 Lowie Vandamme Kon.Brugse Zwemkring BZK/463/94 4:08.38 +0,76 50m: 27.70 27.70 150m: 1:29.35 31.14 250m: 2:32.37 31.71 350m: 3:36.68 32.44 100m: 58.21 30.51 200m: 2:00.66 31.31 300m: 3:04.24 31.87 400m: 4:08.38 31.70 Conor Turner Aer Lingus 1994turn 4:10.39 +0,70 50m: 29.25 29.25 150m: 1:32.87 32.16 250m: 2:36.52 31.65 350m: 3:40.19 31.70 100m: 1:00.71 31.46 200m: -

Summer Newsletter2011

PENGUIN INTERNATIONAL RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB Rugby Football Union Kent County RFU SUMMER NEWSLETTER2011 HSBC PENGUINS TRIUMPH IN THE LONDON TENS! We win the inaugural London 10s Rugby Festival on 5th June at The Athletic Ground in Richmond. Also in this issue: an, HSBC ARFU Rugby Coaching Tour + Coaching in Dubai John Kirw wini and Dean Here + The 2011 Oxford and Cambridge University matches Frank Haddenwn at an scrum do Coaching in Malaysia The Hong Kong 10s ARFU + + HSBC . + King Penguins in Kowloon + Upcoming fixtures + lots more! Coaching Clinic Welcome to the PIRFC Summer Newsletter for 2011. In the pages that follow you will find details of our 2011 coaching HSBC, Grove Industries and Tsunami - and playing trips and details of future events. our sponsors So far this year we have beaten both Oxford and I am sure all members will join with us Cambridge Universities and reached the semi-final of the Hong in expressing our thanks to HSBC, Kong Football Club 10s in March. We also participated in the Grove Industries and Tsunami for their continued support, interest and sponsorship of the Club. London 10s Rugby Festival at the Richmond Athletic Ground, where we managed to prevail against a number of very strong specialist tens outfits. But more of that later. First, we’ll look at what the HSBC Penguin International Coaching Academy has been getting up to in 2011... HSBC Penguin International Coaching Academy News: HSBC Asian 5 Nations Support Coaching 2011 During 2011, the HSBC Penguin International Coaching Academy will be assisting the HSBC Asian 5 Nations and the Asian Rugby Football Union grassroots development programme with visits to many Asian countries. -

IRB World Seven Series)

SEVEN Circuito Mundial de Seven 2007/08 (IRB World Seven Series) Seven de Dubai 31 de noviembre y 1º de diciembre (1st leg WSS 07/08) vs. Fiji 19-31; vs. Australia 19-12; vs. Zimbabwe 12-7; vs. Nueva Zelanda 7-40 (cuartos de final Copa de Oro); vs. Kenia 17-14 (semifinal Copa de Plata); vs. Samoa 15-14 (final Copa de Plata). Plantel: ABADIE, Alejandro (San Fernando - U.R.B.A); AMELONG, Federico (Jockey Club de Rosario - Rosario); BRUZZONE, Nicolás Ariel (S.I.C. - U.R.B.A); CHERRO, Adrián (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); DEL BUSTO, Ramiro José (Los Matreros - U.R.B.A); GOMEZ CORA, Pablo Marcelo (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); GOMEZ CORA, Santiago (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); GONZALEZ AMOROSINO, Lucas Pedro (Pucará - U.R.B.A); GOSIO, Agustín (Club Newman - U.R.B.A.); LALANNE, Alfredo (S.I.C - U.R.B.A.); MERELLO, Francisco José (Regatas de Bella Vista - U.R.B.A); ROMAGNOLI, Andrés Sebastián (San Fernando - U.R.B.A). Staff: Manager: Buenaventura Mínguez Entrenador: Pablo Aprea Fisioterapeuta: Maximiliano Marticorena Seven de George 7 y 8 de diciembre (2nd leg WSS 07/08) vs. Sudáfrica 7-24; vs. Gales 24-14; vs. Uganda 38-7; vs. Samoa 22-19 (cuartos de final Copa de Oro); vs. Nueva Zelanda (semifinal Copa de Oro). Plantel: ABADIE, Alejandro (San Fernando - U.R.B.A); AMELONG, Federico (Jockey Club de Rosario - Rosario); BRUZZONE, Nicolás Ariel (S.I.C. - U.R.B.A); CHERRO, Adrián (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); DEL BUSTO, Ramiro José (Los Matreros - U.R.B.A); GOMEZ CORA, Pablo Marcelo (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); GOMEZ CORA, Santiago (Lomas Athletic - U.R.B.A); GONZALEZ AMOROSINO, Lucas Pedro (Pucará - U.R.B.A); GOSIO, Agustín (Club Newman - U.R.B.A.); LALANNE, Alfredo (S.I.C - U.R.B.A.); MERELLO, Francisco José (Regatas de Bella Vista - U.R.B.A); ROMAGNOLI, Andrés Sebastián (San Fernando - U.R.B.A). -

2000/2012 - L'ovale Azzurro

2000/2012 - L'OVALE AZZURRO Il romanzo del Sei nazioni L’OVALE AZZURRO Della stessa collana 2013 - CENERENTOLA NON ABITA PIU’ QUI Ideazione e coordinamento editoriale: Stefano Tamburini A cura di: Fabrizio Zupo Copertina e progetto grafico: Federico Deidda Realizzazione tecnica: Fabio Di Donna Foto: Archivio Corbis e La Presse Finegil Editoriale Spa Direttore Editoriale: Luigi Vicinanza © Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso, via Cristoforo Colombo, 98 - 00147 Roma Tutti i diritti di Copyright sono riservati. Ogni violazione sarà perseguita a termini di legge Finito di realizzare il 13 febbraio 2014 2 2000/2012 - L'OVALE AZZURRO Il romanzo del Sei nazioni La nazionale di rugby e le sue avventure nel torneo più bello del mondo 2000-2012 L’ovale azzurro a cura di Fabrizio Zupo 3 2000/2012 - L'OVALE AZZURRO 4 2000/2012 - L'OVALE AZZURRO A Piero Rinaldi, compagno di lunghi viaggi rugbistici e fotoreporter. Questo libro è dedicato a Piero Rinaldi, scomparso a Padova il 4 febbraio all'età di 65 anni, da oltre 40 anni fotografo di cronaca con la sua agenzia Candid Camera per quotidiani e fedele documentatore di rugby per diversi quotidiani veneti, riviste specializzate e libri. Rinaldi ha seguito quattro coppe del mondo di rugby a partire dalla prima edizione nel 1987 in Nuovo Zelanda, oltre a mondiali under 20 e universitari, e per tre decenni la nazionale italiana di rugby nei test in Italia e in tour in Europa e nel mondo. Dal 2000 ha seguito il torneo delle Sei nazioni. È tra i fondatori del club ad inviti del XV della Colonna di Padova, selezione veneta che ha incontrato i maggiori club continentali sino a sfidare gli All Blacks di John Kirwan nel 1991. -

Luca Bigi E Ai Suoi Compagni Il Più Sincero E Saranno Sfide Difficili, Anche Rugbistico Degli “In Bocca Al Lupo”

2 SALUTI ISTITUZIONALI 7 CALENDARIO SEI NAZIONI 2021 8 ALBO D’ORO SEI NAZIONI 10 TUTTI I RISULTATI DEL SEI NAZIONI 12 LE CLASSIFICHE DEL SEI NAZIONI 15 LA NAZIONALE 16 STAFF AZZURRO 20 IL CAPITANO AZZURRO 21 GLI AZZURRI 38 IL MINUTAGGIO DEGLI AZZURRI 40 LE STATISTICHE DELLA NAZIONALE 42 LE STATISTICHE DELL’ITALIA AL SEI NAZIONI 46 L’ITALIA AL SEI NAZIONI 47 I TABELLINI DELL’ITALIA DI FRANCO SMITH 49 LE AVVERSARIE 50 LA SCHEDA DELLA FRANCIA 52 LA SCHEDA DEL GALLES 54 LA SCHEDA DELL’INGHILTERRA 56 LA SCHEDA DELL’IRLANDA 58 LA SCHEDA DELLA SCOZIA 60 GLI ARBITRI DELL’ITALIA 64 FORSE NON TUTTI SANNO CHE... NEW HOME KIT INDICE 2020 - 2021 1 67 PROGRAMMA STAMPA SHOP.FEDERUGBY.IT Un anno fa approcciavamo il Guinness Un anno per rilanciarci, un Torneo Sei Nazioni del ventennale con un per tornare ad essere protagonisti. 2 nuovo staff tecnico e le speranze Il 6 febbraio riparte l’avventura degli che sempre accompagnano L’edizione 2021 che, per noi, parte azzurri nel Guinness Six Nations, GLIIL SALUTO ALTRI DEL i nuovi inizi. Nessuno di noi il 6 febbraio all’Olimpico di Roma in un’edizione che assume un AZZURRIPRESIDENTE F.I.R. poteva nemmeno lontanamente contro la Francia, dev’essere un particolare valore, dopo un 2020 prevedere gli stravolgimenti sociali, segnale di speranza per tutti. Per che ha stravolto le nostre vite e lo culturali, economici che avrebbero gli atleti, i tecnici, gli sponsor che ci sport mondiale. Il Sei Nazioni, con caratterizzato il 2020, cambiando per sono rimasti vicini in questi mesi, il suo prestigio, i suoi campioni e sempre il mondo e, di riflesso, il nostro ma soprattutto per gli appassionati, l’attenzione mediatica che è capace sport. -

Amsterdam Swim Cup 2013 Amsterdam, 7 - 8 December 2013

Amsterdam Swim Cup 2013 Amsterdam, 7 - 8 december 2013 Event 17 Women, 50m Freestyle Senioren Open 08-12-2013 - 9:06 Entry list Prelim World Record 23.73 Britta Steffen Rome (ITA) 02-08-2009 European Record 23.73 Britta Steffen Rome (ITA) 02-08-2009 Nederlands Record Senioren 23.96 Marleen Veldhuis Amsterdam 19-04-2009 Nederlands Record Jeugd 25.74 Ranomi Kromowidjojo Palma de Mallorca (ESP) 09-07-2006 Nederlands Record Junioren 26.47 Marrit Steenbergen Utrecht 19-07-2013 Sloterparkbad Record 23.96 Marleen Veldhuis Amsterdam 19-04-2009 Kwalificatietijd EK 2014 Berlijn 25.23 Limiet EJK 2014 Dordrecht meisjes 1998 26.32 Limiet EJK 2014 Dordrecht meisjes 1999 26.61 Richttijd Jeugd OS 2014 Nanjing 25.90 rank name club name entry time 1 Ranomi Kromowidjojo KNZB-NTC 199002156 24.05 L 04-08-2013 Barcelona (ESP) 2 Clarissa van Rheenen PSV 199108270 25.43 L 30-06-2013 Luxembourg (LUX) 3 Tamara van Vliet KNZB-NTC 199403562 25.53 L 04-04-2013 Eindhoven (NED) 4 Maud van der Meer KNZB-NTC 199201180 25.70 L 07-06-2013 Eindhoven (NED) 5 Ilse Kraaijeveld Orca 199002110 25.82 L 02-03-2013 Sindelfingen (GER) 6 Manon Minneboo PSV 199301548 26.05 L 06-07-2012 Paris (FRA) 7 Chantal Senden GZVN GZVN/492/93 26.07 L 29-07-2012 Antwerpen (BEL) 8 Laura Moolenaar AZ&PC 199600656 26.15 L 07-07-2012 Antwerp (BEL) 9 Ally Ponson PSV 199506854 26.27 L 03-08-2013 Barcelona (ESP) 10 Amy de Langen KNZB-RTC 199702046 26.33 L 07-07-2012 Antwerp (BEL) 11 Nelly Velthuijs PSV 199404028 26.43 L 07-06-2013 Eindhoven (NED) 12 Marrit Steenbergen KNZB-RTC 200000086 26.47 L 19-07-2013 Utrecht (NED) 13 Lucy Hope B.E.S.T. -

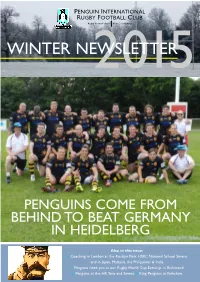

Winter Newsletter2015

PENGUIN INTERNATIONAL RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB Rugby Football Union Kent County RFU WINTER NEWSLETTER2015 PENGUINS COME FROM BEHIND TO BEAT GERMANY IN HEIDELBERG Also in this issue: + Coaching in London at the Rosslyn Park HSBC National School Sevens and in Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines & India + Penguins need you at our Rugby World Cup Evenings in Richmond + Penguins at the HK Tens and Sevens + King Penguins in Yorkshire Many thanks to HSBC who are once again sponsoring the HSBC Penguin Coaching Academy. Welcome to the PIRFC Newsletter for Winter 2015 Going forward, in an agreement that includes World Rugby, HSBC Penguin coaches will be travelling the world to help develop our game through grass roots, development and Since the publication of the last Newsletter the HSBC Penguin coach education activities. International Coaching Academy have coached at the Rosslyn HSBC is a long-term investor in rugby around the world. Park HSBC National School Sevens and paid highly successful Through key partnerships such as the HSBC Sevens World visits to Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines and India. You can read all Series, Australian Rugby Union and the Hong Kong Rugby teams, the bank is helping to develop and grow rugby at all about these events on pages 3 - 8. levels of the game. On the playing front, the Penguin International RFC At the heart of all of their partnerships is HSBC's reached the semi-finals of the GFI Hong Kong Football Club Tens commitment to helping develop the grassroots level of (read CEO Craig Brown’s tournament report on pages 9-11), the game and the HSBC Penguins are a key part of this support.The Penguins are aligned with the bank’s focus on and also played the German Development XV in Heidelberg encouraging youngsters around the world to play rugby, (read Manager Tim Steven’s report on pages 12-14). -

Bravehearts Bound for Pune

COMMONWEALTH YOUTH GAMES SPECIAL EDITION OCTOBER 2008 Congratulating the team, Michael Cavanagh, Chairman Bravehearts bound for Pune of CGS said: “l am confident that we have In August, in the shadow of the Wallace Monument in Stirling, Commonwealth selected an outstanding Games Scotland (CGS) announced the 44 athletes selected to represent Scotland Youth Games Team to compete in Pune, at the third Commonwealth Youth Games in Pune, India 12-18 October 2008. with the standards Michael Cavanagh continuing to rise with Pune 2008 is the first As a result of the global expansion of the every Games cycle. Youth Games to which Games, each country has been allocated all 71 Commonwealth a fixed number of places and qualification “Whilst winning medals is important, the countries have been standards were set accordingly. In a major benefit of the Commonwealth Youth invited to take part number of sports more Scottish athletes Games is exposing young athletes to with 351 medals to met the standards than there were places this level of competition in a multi-sport be won. Scotland available. This is an encouraging sign of environment. It is the ideal preparation will compete in athletes rising to the challenge of meeting event for the Commonwealth Games in eight sports with increasingly tough standards. Delhi in 2010 and Glasgow in 2014. the following number of athletes in each: Based on previous Youth Games results, “I wish them every success and look forward to cheering them on in Pune.” Athletics 10 it is anticipated that many of the Scottish Badminton 4 athletes, all of whom are 18 years of age Boxing 6 or under, who win medals in Pune will Shooting 5 go on to compete for Scotland at the Swimming 10 Commonwealth Games in Delhi in 2010 Table tennis 2 and Glasgow 2014, when they should be at Weightlifting 3 their competitive peak. -

Annual Business Document 2012 Index Item 1 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Welcome to the Annual Report for 2011-2012

SCOTTISH SWIMMING AGM 2012 AGENDA BUSINESS DOCUMENT The Pathfoot Building, University of Stirling 25 th February 2012 11.00 am Scottish Swimming AGM 2012 The Lecture Theatre, Pathfoot Building, University of Stirling Saturday 25th February 2012 List of Acronyms used in this Report ASA Amateur Swimming Association BS British Swimming CEO Chief Executive Officer CPD Continuing Professional Development CPO Child Protection Officer FINA Federation Internationale de Natation LEN Ligue Europeenne de Natation STO Swimming Technical Officials Scottish Swimming AGM The Pathfoot Building, University of Stirling Saturday 25th February 2012 – 11.00am A G E N D A 1. President’s Address 2. Minutes of the Meeting of 26th February 2011 3. Business from Minutes 4. Correspondence 5. Address 5.1 Address by Company Chair 5.2 Company’s Annual Report, which will include reports from National Committees 6. Attendance & Apologies for Absence 7. Financial Report 2010/11 & Budget for 2011/12 8. Company Fees and Fines for 2012/13 9. Alterations to the Governance Documentation 9.1 SASA Constitution 9.2 SASA Articles 9.3 Company Rules 10. Matters the SASA needs to consider as sole member of the Company 11. Notices of Motion 12. Appointment of Members of SASA Council 13. Endorsement of Members of National Committees 14. Confirmation of Appointments 15. Installation of President 16. Presentation of SASA Life Membership: • Neil Valentine Scottish Swimming Annual Business Document 2012 Index Item 1 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Welcome to the Annual Report for 2011-2012. Scottish Swimming continues to be the foremost sport governing body in Scotland, and that is reflected in the continued excellent relationship with sport scotland and their commitment to stable funding until 2014. -

Tuesday 14 January 2014 the Committee Will Meet At

HS/S4/14/1/A HEALTH AND SPORT COMMITTEE AGENDA 1st Meeting, 2014 (Session 4) Tuesday 14 January 2014 The Committee will meet at 9.45 am in Committee Room 2. 1. Support for Community Sport: The Committee will take evidence, in round- table format, from— Morag Arnot, Executive Director, Winning Scotland Foundation; Christine Scullion, Head of Development, The Robertson Trust; Scott Cuthbertson, Community Development Coordinator, Equality Network; Gavin Macleod, Chief Executive Officer, Scottish Disability Sport; Stuart Younie, Service Manager, Sport and Active Recreation, Perth and Kinross Council, Voice of Culture and Leisure; John Howie, Health Improvement Programme Manager – Physical Activity, NHS Health Scotland; Charlie Raeburn, Independent Sports Consultant; Nigel Holl, Chief Executive Officer, scottishathletics; Kim Atkinson, Policy Director, Scottish Sports Association; George Thomson, Chief Executive Officer, Volunteer Scotland. 2. Children and Families Bill (UK Parliament legislation): The Committee will take evidence on legislative consent memorandum LCM(S4) 21.2 from— Michael Matheson, Minister for Public Health, and Kenneth Htet-Khin, Senior Principal Legal Officer, Scottish Government. HS/S4/14/1/A 3. Work programme (in private): The Committee will consider its work programme. Eugene Windsor Clerk to the Health and Sport Committee Room T3.60 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5410 Email: [email protected] HS/S4/14/1/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda Item 1 PRIVATE PAPER HS/S4/14/1/1 (P) Written Submissions HS/S4/14/1/2 Agenda Item 2 Note by the Clerk HS/S4/14/1/3 Agenda Item 3 PRIVATE PAPER HS/S4/14/1/4 (P) HS/S4/14/1/2 Support for Community Sport – One Year On The Robertson Trust Since our response to the original Inquiry in August 2012 The Robertson Trust continues to recognise Community Sport as a priority theme. -

Nr 3, September 2002

Stänk från TÄBY SIM Nr 3, September 2002 1 Stänk från TÄBY SIM TÄBY SIM - Föreningen för simsport och motion - Adress: Simhallen, 183 34 TÄBY Tel/fax: 768 15 44 Hemsida/ E-post: www.idrott.nu/tabysim (hemsida), [email protected] (tävl. simning), [email protected] (simskola,Plask o Lek). Postgiro: 14 77 00 - 9 (medlemsavg), 81 55 5-5 (ekonomi) Kansli: I simhallen, bakom spärrarna, på entréplan Stänkbidrag: I informationskommitténs fack i kansliet eller via E-post. Arbete Bostad Huvudtränare: Gunnar Fornander 768 63 27 Simskola & kansli: Anki Fagerberg 768 15 44 511 87 505 Plask & lek ansvarig: Carl Johan Hellman 788 80 18 756 24 34 Ansvarig - konstsim: Elisabeth Andersson 758 82 06 MBK ansvarig: Sven Sahlström 758 87 41 Mastersansvarig: Stefan Eriksson 630 21 71 756 65 98 Revisorer: Philip von Schoultz (ordinarie) 0708-307657 756 47 84 Jonas Lögdberg (ordinarie) 0709-253231 623 17 23 Björn Eklöf (suppleant) 756 25 07 Valberedning: Gunnar Fornander (ordf) 768 63 27 Ann-Christin Fagerberg 768 15 44 Lennart Andersson 758 82 06 STYRELSEN Ledamöter: Ordförande: Carl Johan Hellman 756 24 34 Kassör: Febe Thulin 070-7820099 Sekreterare: Marie Håkansson 758 10 87 Simkommitté: Lennart Eklöf 510 119 97 Konstsimskommitté: Lena Björkestam 510 119 90 Utbildningskommitté: Elisabeth Andersson 758 82 06 Infokommitté/vice ordf.: Johan Finnved 070-849 99 12 768 82 55 Resurskommitté: Christer Pellfolk Stödkommitté: Margit Eklöf 510 119 97 Suppleanter: Simkommitté: Mats Johansson, 768 64 38 Agneta Timbäck 540 230 81 Konstsimskommitté: Susanne Shelley