Pseudoscops Clamator (Striped Owl)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of Neuromorphology, and the Co-Localization of Glial Related Markers in the Brains of Striped Owl (Asio Clamator) from North East Nigeria

Niger. J. Physiol. Sci. 35 (June 2020): 109 - 113 www.njps.physiologicalsociety.com Research Article Some Aspects of Neuromorphology, and the Co-localization of Glial Related Markers in the Brains of Striped Owl (Asio clamator) from North East Nigeria Karatu A.La., Olopade, F.Eb., Folarin, O.Rc., Ladagu. A.Dd., *Olopade, J.Od and Kwari, H.Da aDepartment of Veterinary Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria bDepartment of Anatomy, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria cDepartment of Biomedical Laboratory Medical Science, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria dDepartment of Veterinary Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Summary: The striped owl (Asio clamator) is unique with its brownish white facial disc and they are found in the north eastern part of Nigeria. Little is known in the literature on the basic neuroanatomy of this species. This study focuses on the histology and glial expression of some brain regions of the striped owl. Five owls were obtained in the wild, and their brains were routinely prepared for Haematoxylin and Eosin, and Cresyl violet staining. Immunostaining was done with anti- Calbindin, anti MBP, anti-GFAP, and anti-Iba-1 antibodies; for the expression of cerebellar Purkinje cells and white matter, cerebral astrocytes and microglia cells respectively. These were qualitatively described. We found that the hippocampal formation of the striped owl, though unique, is very similar to what is seen in mammals. The cerebellar cortex is convoluted, has a single layer of Purkinje cells with profuse dendritic arborization, a distinct external granular cell layer, and a prominent stem of white matter were seen in this study. -

Tc & Forward & Owls-I-IX

USDA Forest Service 1997 General Technical Report NC-190 Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere Second International Symposium February 5-9, 1997 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Editors: James R. Duncan, Zoologist, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Department of Natural Resources Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB CANADA R3J 3W3 <[email protected]> David H. Johnson, Wildlife Ecologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA, USA 98501-1091 <[email protected]> Thomas H. Nicholls, retired formerly Project Leader and Research Plant Pathologist and Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN, USA 55108-6148 <[email protected]> I 2nd Owl Symposium SPONSORS: (Listing of all symposium and publication sponsors, e.g., those donating $$) 1987 International Owl Symposium Fund; Jack Israel Schrieber Memorial Trust c/o Zoological Society of Manitoba; Lady Grayl Fund; Manitoba Hydro; Manitoba Natural Resources; Manitoba Naturalists Society; Manitoba Critical Wildlife Habitat Program; Metro Propane Ltd.; Pine Falls Paper Company; Raptor Research Foundation; Raptor Education Group, Inc.; Raptor Research Center of Boise State University, Boise, Idaho; Repap Manitoba; Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada; USDI Bureau of Land Management; USDI Fish and Wildlife Service; USDA Forest Service, including the North Central Forest Experiment Station; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; The Wildlife Society - Washington Chapter; Wildlife Habitat Canada; Robert Bateman; Lawrence Blus; Nancy Claflin; Richard Clark; James Duncan; Bob Gehlert; Marge Gibson; Mary Houston; Stuart Houston; Edgar Jones; Katherine McKeever; Robert Nero; Glenn Proudfoot; Catherine Rich; Spencer Sealy; Mark Sobchuk; Tom Sproat; Peter Stacey; and Catherine Thexton. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

February/March 2021 NYS Conservationist Magazine

NEW YORK STATE $3.50 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2021 MovingMa\,inga a MMOOSEQOSE Getting Outdoors in Winter Counting the Fish in the Sea Winter’s Beauty CONSERVATIONIST Dear Readers, Volume 75, Number 4 | February/March 2021 During these challenging times, Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor of New York State I encourage you to take advantage DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION of the opportunities we have to Basil Seggos, Commissioner enjoy nature. For some people, Erica Ringewald, Deputy Commissioner for Public Affairs Harold Evans, Director of Office of Communication Services this time of year provides a THE CONSERVATIONIST STAFF chance to enjoy various outdoor Eileen C. Stegemann, Managing Editor winter adventures, while others Peter Constantakes, Assistant Editor look forward to the coming Tony Colyer-Pendas, Assistant Editor Megan Ciotti, Business Manager change of season, with warming Jeremy J. Taylor, Editor, Conservationist for Kids temperatures, the disappearance Rick Georgeson, Contributing Editor of snow, and di˜erent ways to get outside. DESIGN TEAM In this issue, we highlight some amazing photos of Andy Breedlove, Photographer/Designer Jim Clayton, Chief, Multimedia Services New°York’s winter beauty and celebrate a great winter Mark Kerwin, Art Director/Graphic Designer sport—snowmobiling—which can be enjoyed on more than Robin-Lucie Kuiper, Photographer/Designer 10,000 miles of trails throughout the state (pg. 12). You can Mary Elizabeth Maguire, Graphic Designer Jennifer Peyser, Graphic Designer also read about a native Floridian who moved to New York Maria VanWie, Graphic Designer and learned to cross country ski – and how that changed his EDITORIAL OFFICES view of the heavy snowfall we experienced this winter. -

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Gu

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Guajira, Boyacá, Distrito Capital de Bogotá, Caldas These comments are provided to help independent birders traveling in Colombia, particularly people who want to drive themselves to birding sites rather than taking public transportation and also want to book reservations directly with lodgings and reserves rather than using a ground agent or tour company. Many trip reports provide GPS waypoints for navigation. I used GoogleEarth/ Maps, which worked fine for most locations (not for El Paujil reserve). I paid $10/day for AT&T to hook me up to Claro, Movistar, or Tigo through their Passport program. Others get a local SIM card so that they have a Colombian number (cheaper, for sure); still others use GooglePhones, which provide connection through other providers with better or worse success, depending on the location in Colombia. For transportation, I used a rental 4x4 SUV to reach places with bad roads but also, in northern Colombia, a subcompact rental car as far as Minca (hiked in higher elevations, with one moto-taxi to reach El Dorado lodge) and for La Guajira. I used regular taxis on few occasions. The only roads to sites for Fuertes’s Parrot and Yellow-eared Parrot could not have been traversed without four-wheel drive and high clearance, and this is important to emphasize: vehicles without these attributes would have been useless, or become damaged or stranded. Note that large cities in Colombia (at least Medellín, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) have restrictions on driving during rush hours with certain license plate numbers (they base restrictions on the plate’s final numeral). -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help. -

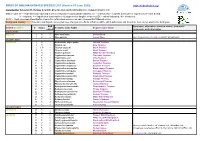

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Adaptive Significance of Ear Tufts in Owls

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 383 Condor 83:383-384 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1981 ADAPTIVE SIGNIFICANCE OF of a broken vertical branch. This effect is possible be- cause owls sit upright and most are colored in gray- EAR TUFTS IN OWLS browns and grays. The camouflage effect can occur only if owls with ear tufts roost on branches in daylight. Diurnal owls MICHAEL PERRONE, JR. often would lose the camouflage effect because of their activity. Furthermore, they roost chiefly at night when darkness itself hides them from visually directed ani- About 50 of the worlds’ 132 species of owls have on mals and makes ear tufts superfluous as camouflage. their heads tufts of feathers commonly called “ears” or Thus the camouflage hypothesis predicts the presence “horns.” The adaptive value of ear tufts has been con- of conspicuous ear tufts only on nocturnal owls that strued in two ways. First, the presence or absence of roost in trees or shrubs and predicts their absence on tufts may help distinguish species at short range all diurnal species. (Sparks and Soper 1970, Burton 1973). That is, tufts The species recognition hypothesis likewise pre- provide a silhouette which, when combined with dicts the absence of ear tufts on diurnal owls, since voice, facilitates species recognition; owls can see well such species presumably need not rely on silhouettes enough at night to distinguish head shapes, and tufted for identification. Thus, if diurnal species have con- and untufted species are often sympatric. spicuous ear tufts, both the camouflage and species Mysterud and Dunker (1979) proposed that ear tufts recognition hypotheses are weakened. -

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World

Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World EUGENE M. McCARTHY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World This page intentionally left blank Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World EUGENE M. MC CARTHY 3 2006 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugual Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McCarthy, Eugene M. Handbook of avian hybrids of the world/Eugene M. McCarthy. p. cm. ISBN-13 978-0-19-518323-8 ISBN 0-19-518323-1 1. Birds—Hybridization. 2. Birds—Hybridization—Bibliography. I. Title. QL696.5.M33 2005 598′.01′2—dc22 2005010653 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Rebecca, Clara, and Margaret This page intentionally left blank For he who is acquainted with the paths of nature, will more readily observe her deviations; and vice versa, he who has learnt her deviations, will be able more accurately to describe her paths. -

Readingsample

Owls (Strigiformes) Annotated and Illustrated Checklist Bearbeitet von Friedhelm Weick 1. Auflage 2006. Buch. XXXIV, 350 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 540 35234 1 Format (B x L): 17,8 x 25,4 cm Gewicht: 1008 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Biowissenschaften allgemein > Ökologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Uroglaux 231 Genus Remarks: Formerly regarded as closely allied to genus Uroglaux Mayr 1937 Ninox, but with rounded instead of pointed wings. Uroglaux Uroglaux Mayr 1937, Am. Mus. Novit. 939: 6. Type by Relationship to genus Sceloglaux questionable; Athene dimorpha Salvadori 1874 both are probably relict species! Wing length: 200–225 mm Uroglaux dimorpha (Salvadori) 1874 Tail length: 145–156 mm Papuan Hawk Owl · Rundflügelkauz · Chouette ou Ninoxe Tarsus length: 32 and 33 mm papoue · Ninox Hálcon Length of bill: 30 mm Athene dimorpha Salvadori, 1874, Ann. Mus. Civ. Genova, 6: 308; Body mass: ? Terra typica: Sorong, New Guinea Illustration: W. Hart in Gould 1875–1888, vol 1: Pl. 7; Length: 300–340 mm T. Medland in Iredale 1956: Pl. 7; Grossman and Body mass: ? Hamlet 1965: 439 (b/w); D. Zimmerman in Beehler et al. 1986: 131 (b/w line drawing); T. Boyer in Boyer Distribution: Northwest New Guinea: Irian Jaya. South- and Hume 1991: 111; J.