Adaptive Significance of Ear Tufts in Owls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of Neuromorphology, and the Co-Localization of Glial Related Markers in the Brains of Striped Owl (Asio Clamator) from North East Nigeria

Niger. J. Physiol. Sci. 35 (June 2020): 109 - 113 www.njps.physiologicalsociety.com Research Article Some Aspects of Neuromorphology, and the Co-localization of Glial Related Markers in the Brains of Striped Owl (Asio clamator) from North East Nigeria Karatu A.La., Olopade, F.Eb., Folarin, O.Rc., Ladagu. A.Dd., *Olopade, J.Od and Kwari, H.Da aDepartment of Veterinary Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria bDepartment of Anatomy, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria cDepartment of Biomedical Laboratory Medical Science, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria dDepartment of Veterinary Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Summary: The striped owl (Asio clamator) is unique with its brownish white facial disc and they are found in the north eastern part of Nigeria. Little is known in the literature on the basic neuroanatomy of this species. This study focuses on the histology and glial expression of some brain regions of the striped owl. Five owls were obtained in the wild, and their brains were routinely prepared for Haematoxylin and Eosin, and Cresyl violet staining. Immunostaining was done with anti- Calbindin, anti MBP, anti-GFAP, and anti-Iba-1 antibodies; for the expression of cerebellar Purkinje cells and white matter, cerebral astrocytes and microglia cells respectively. These were qualitatively described. We found that the hippocampal formation of the striped owl, though unique, is very similar to what is seen in mammals. The cerebellar cortex is convoluted, has a single layer of Purkinje cells with profuse dendritic arborization, a distinct external granular cell layer, and a prominent stem of white matter were seen in this study. -

Tc & Forward & Owls-I-IX

USDA Forest Service 1997 General Technical Report NC-190 Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere Second International Symposium February 5-9, 1997 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Editors: James R. Duncan, Zoologist, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Department of Natural Resources Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB CANADA R3J 3W3 <[email protected]> David H. Johnson, Wildlife Ecologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA, USA 98501-1091 <[email protected]> Thomas H. Nicholls, retired formerly Project Leader and Research Plant Pathologist and Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN, USA 55108-6148 <[email protected]> I 2nd Owl Symposium SPONSORS: (Listing of all symposium and publication sponsors, e.g., those donating $$) 1987 International Owl Symposium Fund; Jack Israel Schrieber Memorial Trust c/o Zoological Society of Manitoba; Lady Grayl Fund; Manitoba Hydro; Manitoba Natural Resources; Manitoba Naturalists Society; Manitoba Critical Wildlife Habitat Program; Metro Propane Ltd.; Pine Falls Paper Company; Raptor Research Foundation; Raptor Education Group, Inc.; Raptor Research Center of Boise State University, Boise, Idaho; Repap Manitoba; Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada; USDI Bureau of Land Management; USDI Fish and Wildlife Service; USDA Forest Service, including the North Central Forest Experiment Station; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; The Wildlife Society - Washington Chapter; Wildlife Habitat Canada; Robert Bateman; Lawrence Blus; Nancy Claflin; Richard Clark; James Duncan; Bob Gehlert; Marge Gibson; Mary Houston; Stuart Houston; Edgar Jones; Katherine McKeever; Robert Nero; Glenn Proudfoot; Catherine Rich; Spencer Sealy; Mark Sobchuk; Tom Sproat; Peter Stacey; and Catherine Thexton. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

February/March 2021 NYS Conservationist Magazine

NEW YORK STATE $3.50 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2021 MovingMa\,inga a MMOOSEQOSE Getting Outdoors in Winter Counting the Fish in the Sea Winter’s Beauty CONSERVATIONIST Dear Readers, Volume 75, Number 4 | February/March 2021 During these challenging times, Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor of New York State I encourage you to take advantage DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION of the opportunities we have to Basil Seggos, Commissioner enjoy nature. For some people, Erica Ringewald, Deputy Commissioner for Public Affairs Harold Evans, Director of Office of Communication Services this time of year provides a THE CONSERVATIONIST STAFF chance to enjoy various outdoor Eileen C. Stegemann, Managing Editor winter adventures, while others Peter Constantakes, Assistant Editor look forward to the coming Tony Colyer-Pendas, Assistant Editor Megan Ciotti, Business Manager change of season, with warming Jeremy J. Taylor, Editor, Conservationist for Kids temperatures, the disappearance Rick Georgeson, Contributing Editor of snow, and di˜erent ways to get outside. DESIGN TEAM In this issue, we highlight some amazing photos of Andy Breedlove, Photographer/Designer Jim Clayton, Chief, Multimedia Services New°York’s winter beauty and celebrate a great winter Mark Kerwin, Art Director/Graphic Designer sport—snowmobiling—which can be enjoyed on more than Robin-Lucie Kuiper, Photographer/Designer 10,000 miles of trails throughout the state (pg. 12). You can Mary Elizabeth Maguire, Graphic Designer Jennifer Peyser, Graphic Designer also read about a native Floridian who moved to New York Maria VanWie, Graphic Designer and learned to cross country ski – and how that changed his EDITORIAL OFFICES view of the heavy snowfall we experienced this winter. -

Birds New Zealand No. 11

No. 11 September 2016 Birds New Zealand The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NO. 11 SEPTEMBER 2016 Proud supporter of Birds New Zealand Proud supporter of 3 President’s Report Birds New Zealand 5 New Birdwatching Location Maps We are thrilled with our decision 7 Subantarctic Penguins’ Marathon ‘Migration’ to support Birds New Zealand. Fruzio’s aim is to raise awareness of the dedicated 8 Laughing Owl related to Morepork work of Birds New Zealand and to enable wider public engagement with the organisation. We have 9 Fiordland Crested Penguin Update re-shaped our marketing strategy and made a firm commitment of $100,000 to be donated over the 11 Ancient New Zealand Wrens course of the next 3 years. Follow our journey on: www.facebook/fruzio. 12 Are Hihi Firing Blanks? 13 Birding Places - Waipu Estuary PUBLISHERS Hugh Clifford Tribute Published on behalf of the members of the Ornithological Society of 14 New Zealand (Inc). P.O. Box 834, Nelson 7040, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] 15 Minutes of the 77th AGM Website: www.osnz.org.nz Editor: Michael Szabo, 6/238, The Esplanade, Island Bay, Wellington 6023. Phone: (04) 383 5784 16 Regional Roundup Email: [email protected] ISSN 2357-1586 (Print) ISSN 2357-1594 (Online) 19 Bird News We welcome advertising enquiries. Free classified ads are available to members at the editor’s discretion. Articles and illustrations related to birds, birdwatching or ornithology in New Zealand and the South Pacific region for inclusion in Birds New Zealand are welcome in electronic form, including news about about birds, COVER IMAGE members’ activities, bird studies, birding sites, identification, letters to the editor, Front cover: Fiordland Crested Penguin or Tawaki in rainforest reviews, photographs and paintings. -

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Gu

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Guajira, Boyacá, Distrito Capital de Bogotá, Caldas These comments are provided to help independent birders traveling in Colombia, particularly people who want to drive themselves to birding sites rather than taking public transportation and also want to book reservations directly with lodgings and reserves rather than using a ground agent or tour company. Many trip reports provide GPS waypoints for navigation. I used GoogleEarth/ Maps, which worked fine for most locations (not for El Paujil reserve). I paid $10/day for AT&T to hook me up to Claro, Movistar, or Tigo through their Passport program. Others get a local SIM card so that they have a Colombian number (cheaper, for sure); still others use GooglePhones, which provide connection through other providers with better or worse success, depending on the location in Colombia. For transportation, I used a rental 4x4 SUV to reach places with bad roads but also, in northern Colombia, a subcompact rental car as far as Minca (hiked in higher elevations, with one moto-taxi to reach El Dorado lodge) and for La Guajira. I used regular taxis on few occasions. The only roads to sites for Fuertes’s Parrot and Yellow-eared Parrot could not have been traversed without four-wheel drive and high clearance, and this is important to emphasize: vehicles without these attributes would have been useless, or become damaged or stranded. Note that large cities in Colombia (at least Medellín, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) have restrictions on driving during rush hours with certain license plate numbers (they base restrictions on the plate’s final numeral). -

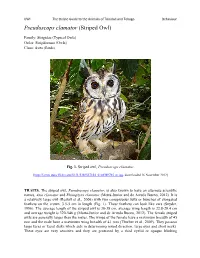

Pseudoscops Clamator (Striped Owl)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Pseudoscops clamator (Striped Owl) Family: Strigidae (Typical Owls) Order: Strigiformes (Owls) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Striped owl, Pseudoscops clamator. [http://farm6.staticflickr.com/5131/5389557854_01083b97b5_m.jpg, downloaded 16 November 2012] TRAITS. The striped owl, Pseudoscops clamator, is also known to have an alternate scientific names, Asio clamator and Rhinoptynx clamator (Motta-Junior and de Arruda Bueno, 2012). It is a relatively large owl (Restall et al., 2006) with two conspicuous tufts or bunches of elongated feathers on the crown, 3.5-5 cm in length (Fig. 1). These feathers can look like ears (Snyder, 1996). The average length of the striped owl is 30-38 cm, average wing length is 22.8-29.4 cm and average weight is 320-546 g (Motta-Junior and de Arruda Bueno, 2012). The female striped owls are generally larger than the males. The wings of the female have a maximum breadth of 45 mm and the male have a maximum wing breadth of 41 mm (Thurber et al., 2009). They possess large faces or facial disks which aids in determining sound direction, large eyes and short necks. These eyes are very sensitive and they are protected by a third eyelid or opaque blinking UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour membrane. They have two ear openings, one on each side of the head that are slightly different in size from each other. A majority of their bodies, including the lower legs and toes, are covered with long, soft feathers. -

Distributions of New Zealand Birds on Real and Virtual Islands

JARED M. DIAMOND 37 Department of Physiology, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, California 90024, USA DISTRIBUTIONS OF NEW ZEALAND BIRDS ON REAL AND VIRTUAL ISLANDS Summary: This paper considers how habitat geometry affects New Zealand bird distributions on land-bridge islands, oceanic islands, and forest patches. The data base consists of distributions of 60 native land and freshwater bird species on 31 islands. A theoretical section examines how species incidences should vary with factors such as population density, island area, and dispersal ability, in two cases: immigration possible or impossible. New Zealand bird species are divided into water-crossers and non-crossers on the basis of six types of evidence. Overwater colonists of New Zealand from Australia tend to evolve into non-crossers through becoming flightless or else acquiring a fear of flying over water. The number of land-bridge islands occupied per species increases with abundance and is greater for water-crossers than for non-crossers, as expected theoretically. Non-crossers are virtually restricted to large land-bridge islands. The ability to occupy small islands correlates with abundance. Some absences of species from particular islands are due to man- caused extinctions, unfulfilled habitat requirements, or lack of foster hosts. However, many absences have no such explanation and simply represent extinctions that could not be (or have not yet been) reversed by immigrations. Extinctions of native forest species due to forest fragmentation on Banks Peninsula have especially befallen non-crossers, uncommon species, and species with large area requirements. In forest fragments throughout New Zealand the distributions and area requirements of species reflect their population density and dispersal ability. -

Typical Owls Subfamily BUBONINAE Vigors: Hawk-Owls and Allies

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 264 & 266. Order STRIGIFORMES: Owls Regarding the following nomina dubia, see under genus Aegotheles Vigors & Horsfield: Strix parvissima Ellman, 1861: Zoologist 19: 7465. Nomen dubium. Strix parvissima Potts, 1871: Trans. N.Z. Inst. 3: 68 – Rangitata River, Canterbury. Nomen dubium. Athene (Strix) parvissima Potts; Potts 1873, Trans. N.Z. Inst. 5: 172. Nomen dubium Family STRIGIDAE Leach: Typical Owls Strigidae Leach, 1819: Eleventh room. In Synopsis Contents British Museum 15th Edition, London: 64 – Type genus Strix Linnaeus, 1758. Subfamily BUBONINAE Vigors: Hawk-owls and Allies Bubonina Vigors, 1825: Zoological Journal 2: 393 – Type genus Bubo Dumeril, 1805. Genus † Sceloglaux Kaup Sceloglaux Kaup, 1848: Isis von Oken, Heft 41: col. 768 – Type species (by monotypy) Athene albifacies G.R. Gray, 1844 = Sceloglaux albifacies (G.R. Gray). As a subgenus of Ninox. A monotypic genus endemic to New Zealand. König et al. (1999) noted that the laughing owl and the fearful owl Nesasio solomonensis of the Solomon Islands were very similar species but whether this is due to a relationship or convergence is unknown. † Sceloglaux albifacies (G.R. Gray) Laughing Owl Extinct. Known from North and South Islands and Stewart Island / Rakiura. Fossils of this owl, especially at sites where they accumulated food remains, are abundant in drier eastern regions of both main islands (Worthy & Holdaway 2002). -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

From-Moa-To-Dinosaurs-Short-Blad.Pdf

For my brother Andrew, who found the best fossil — GC For Graham, always a source of inspiration — NB Gillian Candler is an award-winning author who brings her knowledge and skills in education and publishing to her passion for the natural world. She has always been intrigued by how New Zealand must have looked to the very first people who set foot here, and wanted to find out more about what animals lived here then. She found her first fossil when she was 5 years old – an experience she’ll never forget – and it opened up a whole new world of interest. contents Ned Barraud is an illustrator with a keen passion for the natural world. For him, this book was a perfect opportunity Travel back in time 4 to put on paper some of the most bizarre and fascinating creatures from New Zealand’s past. Ned lives in Wellington The changing land 6 with his wife and three children. Around 1000 years ago 8 The forest at night 10 other books in the explore & discover series In the mountains 12 All about moa 14 Many thanks to Alan Tennyson for his advice on the text Other extinct birds 16 and illustrations. The maps on pages 6–7 are based on those in George Gibbs’ book, Ghosts of Gondwana: A history of life in Survivors from the past 18 New Zealand. Around 19 million years ago 20 First published in 2016 by Animals of Lake Manuherikia 22 Potton & Burton 98 Vickerman Street, PO Box 5128, Nelson, The seas of Zealandia 24 New Zealand www.pottonandburton.co.nz Ancient sea creatures 26 Illustrations © Ned Barraud; text © Gillian Candler Around 80 million years ago 28 ISBN PB 978 0 947503 09 3; HB 978 0 947503 10 9 Dinosaurs and more 30 Printed in China by Midas Printing International Ltd Life on Gondwana 32 This book is copyright.