Foreign Ownership in Australian Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOLUME 7 No. 7 July 2014 ISSN 1835-7628 DIARY July Saturday

VOLUME 7 No. 7 July 2014 ISSN 1835-7628 FROM THE EDITOR ed. There is too, something from the event that must lift Australian pride - the faith, trust and peaceful enjoyment. Jim Boyce, our President, has spent some time in hospital Where else in the world does the first Minister attend a in the past week. We all wish him the very best and a public event where it was hard to identify the presence of speedy recovery. escort or security? As you will surely have noticed, Jim is a major contributor Warringah Australia Remembers, held under peerless blue to our newsletters and his absence creates a substantial sky, the Sun so bright the cheeks cried out for relief whilst gap. There is no President’s Report this month and there the body rejoiced in the near summer warming. We will not be a monthly meeting during July. would not have had it otherwise; idyllic for this annual outdoor event that the media and wider public let slip. Thank you to the authors of the various articles in this There are few opportunities to take the children of today issue - Keith Amos, George Champion, Shelagh Champion, to glimpse the world of long ago, when peace in our time Rose Cullen and Jim (I had two of his articles in the was the goal of our leaders. pipeline). I welcome all contributions - small or large - so please send them in. The service, held on Friday 30 May, commemorated Syd- As has been mentioned previously, there is a lot of work ney becoming a target for attack by enemy forces in a (and expense) in producing and mailing hard copies of the world that was yet to come to terms with the futility of Newsletter. -

Chillout an Oxford Cold Storage Publication

Chillout An Oxford Cold Storage publication Issue 18 – December 2013 Message from Management In this issue : Paul Fleiszig Message from Management New Activities and skills Transport & Training reports Achievements Welcome to the 2013 Oxford newsletter. This year has been O H & S Hatched and Matched another successful year for the Oxford Logistics Group. We have all Years of Service, and more ! met many challenges and taken a number of opportunities. This newsletter will cover some of the commercial and personal highlights for our ‘Oxford family’ for the year. 2013 has seen Oxford grow again. We completed our 13B extension in October on budget and with minimal delay. The new store holds about 23,000 pallets in two rooms. The 13B complex is built using the latest energy saving & operating technology. The key new feature is the implementation of mobile racking. This is a first for Oxford. The implementation gave us many challenges, which our engineering & IT teams in conjunction with our builders Vaughan Construction and racking providers & contractors Dematic, Storax, Barpro & One Stop Shelving overcame brilliantly. More details regarding the mobile racking & the other new features built into our new store can be found within this newsletter. We commenced 2013 with storage at capacity. We struggled to handle the storage volumes our customers wanted us to hold for them. Our Store Management and Staff managed the ‘over capacity’ issues extremely well. We maintained high levels of service for all our customers in very difficult circumstances. It is a credit to the professionalism & dedication of all our staff. We ran most of our stores at near capacity for a large part of the year. -

DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition

Dairy Industry Association of Australia DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition 2017 Results DUCT C ODUCT C RO ROM OM P P P P Y Y E E R T IR I T I I A A T T D D I I O O N N N N A A 2 2 I I 0 0 R R 1 1 O O 7 7 T T C C I I V V R E L D V GO SIL RESULTS – 2017 Results Booklet 2017 DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition n n Butter ................................................................................. 4 n n Cheese ............................................................................... 5 n n Dips ...................................................................................11 n n Powder .............................................................................11 n n Yoghurt ............................................................................12 n n Milk ...................................................................................15 n n Cream ...............................................................................18 n n Dairy desserts ................................................................19 n n Innovation ......................................................................19 n n Ice-cream, gelati, frozen yoghurt ...........................19 n n Non-bovine product ...................................................23 n n Organic products .........................................................24 n n Other ................................................................................24 The DIAA thanks its National Partners DIAA VICTORIAN DAIRY PRODUCT COMPETITION INDUSTRY-SPONSORED -

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery Chs 55 Peters Foods Pty Ltd Collection

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 55 PETERS FOODS PTY LTD COLLECTION Ice Cream, Launceston Food Production Establishments, Launceston INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.Record Books 2.Minutes of Meetings 3.Correspondence 4.Publications 5.Newspaper Cuttings 6.Sample Books, Product Wrappers 7.Miscellaneous Records 8.Ephemera OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION Peters Ice Cream (Vic.), which commenced operations in Melbourne in 1929, began distributing its products in Tasmania in 1932. Distribution was undertaken by Johnstone & Wilmot Pty Ltd until 1947, when Peters’ York Street premises took over. Later the York Street building became Peters frozen foods store. Airfreight from Victoria replaced sea transport in 1949. Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) Pty Ltd, a subsidiary company of Peters Ice Cream (Vic.), was established in 1954 to conduct Peters operations in Tasmania. The company built a factory on a 12 acre site at 89- 99 Talbot Road, Launceston (previously an apple orchard) and on 11 July 1955 the factory made its first ice cream in Tasmania. Full production began in June 1956. Several houses were built on the property for key staff. Set in landscaped grounds, the factory became a popular tourist attraction. In Peters Ice Cream (Vic.) Ltd 1962 annual report it was noted that the manufacture and distribution of crumpets had started on an experimental basis in Launceston as an added line for winter months. That year Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) acquired the Tasmanian Ice Cream Co. Pty Ltd. By 1964 Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) had depots in Hobart, Devonport, Burnie, Ulverstone, Queenstown and St Marys. In addition to making ice cream, the company marketed products from the northwest coast under the Birdseye, Farmer Ed and Hy. -

List of Food Samples for Testing of Melamine IO 29.9.2008 V3

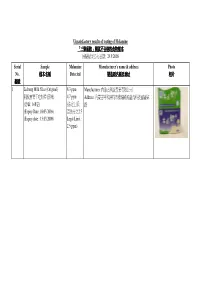

Unsatisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試不合格的食物樣本」測試不合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Melamine Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 Detected 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 1 Licheng Milk Slice (Original) 8.3 ppm Manufacturer: 內蒙古利誠實業有限公司 利誠實業干吃奶片(原味) 4.7 ppm Address: 內蒙古呼和浩特市機塲路鴻盛高科技園區緯二 (淨重: 168 克) (法定上限: 路 (Expiry Date: 10.03.2009) 百萬分之2.5 (Expiry date : 13.03.2009) Legal Limit : 2.5 ppm) Satisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試合格的食物樣本」測試合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 1 Meiji Hohoemi Milkpowder Cube (Net Weight: Manufacturer: Meiji Dairies Corporation 108 g) Address: 1-2-10, Shinsuna, Koto-ku, Tokyo (Expiry date : 21.6.2009) 明治乳業株式會社KS 東京都江東區新砂1-2-10 2 Icero Follow Momo Milk Powder Above 9 Month Manufacturer: Icero Co., Ltd. (Net Weight: 900 g) Address: 16-23, Minato 4-Shibaura, Minato-ku, (Expiry date : 14.10.2009) Tokyo, Japan 3 Gerber Graduates Finger Foods Biter Biscuits Manufacturer: Gerber Products Company (Net weight 5 oz (142g)) Address: Fremont, MI 49413, USA (Expiry date : 25.4.2010) Satisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試合格的食物樣本」測試合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 4 Heinz Smooth Strawberry Yoghurt Dessert (110g Manufacturer: H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited Net) Address: 105 Camberwell Road, Hawthorn East, Victoria 3123 (All ages from 6 months) Australia (Expiry date : 24.3.2010) 5 Kameda Haihain (Weight 53g) Manufacturer: Kameda Seika Company Limited (Expiry date : 22.12.2008) Address: 3-1-1 Kamedakogyodanch Konan Nigata Nigata, Japan Product of Japan 6 Takara Animal Mate Biscuits (Net Weight 340g) Manufacturer: Takara Confectionery Co., Ltd. -

One Year to Go

NEWS 10TH EDITION APRIL 2005 CHAIRMAN’S ONE YEAR TO GO MESSAGE As we celebrate one year to go until the Opening Ceremony of the Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games, it is timely to reflect on signifcant milestones that have occurred in the first few months of 2005. During January, Federal Treasurer the Hon. Peter Costello launched the Melbourne 2006 Volunteer Program at Melbourne’s Federation Square. The program received an overwhelming response, with applications closing just a week later as subscription levels of 20,000 were reached. The Volunteer launch in January was followed by the unveiling of the Queen’s Baton Relay international route by Prime Minister John Howard and Victorian Premier Steve Bracks in Canberra on 10 February. At Buckingham Palace, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II presided over the ceremony that launched the innovative Baton on the longest, most inclusive relay in Commonwealth Games history, covering over 180,000 km and every ocean and continent in the world. We were also delighted to welcome several new sponsors to the Commonwealth Games Family. Telstra became the fourth M2006 Partner, while Nestlé Peters were welcomed as a Games Sponsor. Yakka and the Royal Australian Mint jointed the team as Official Providers. Our media family has Above: More than 1000 stakeholders gather at Rod Laver Arena to celebrate the milestone. Participants included athletes, also expanded, with Southern Cross sponsors, emergency service workers and government representatives. Broadcasting and ABC Radio joining as our official radio broadcasters. The Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games ‘family’ celebrated one year to go until the And last, but far from least, the Games Opening Ceremony of the Melbourne Games by creating a giant ‘1’ at Rod Laver Arena ticket ballot opened on 13 March. -

222 Results Found for Your Search Criteria

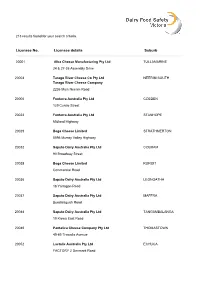

213 results found for your search criteria. Licensee No. Licensee details Suburb 20001 Alba Cheese Manufacturing Pty Ltd TULLAMARINE 24 & 27-35 Assembly Drive 20003 Tarago River Cheese Co Pty Ltd NEERIM SOUTH Tarago River Cheese Company 2236 Main Neerim Road 20006 Fonterra Australia Pty Ltd COBDEN 129 Curdie Street 20023 Fonterra Australia Pty Ltd STANHOPE Midland Highway 20029 Bega Cheese Limited STRATHMERTON 5096 Murray Valley Highway 20032 Saputo Dairy Australia Pty Ltd COBRAM 90 Broadway Street 20035 Bega Cheese Limited KOROIT Commercial Road 20036 Saputo Dairy Australia Pty Ltd LEONGATHA 18 Yarragon Road 20037 Saputo Dairy Australia Pty Ltd MAFFRA Bundalaguah Road 20044 Saputo Dairy Australia Pty Ltd TANGAMBALANGA 19 Kiewa East Road 20046 Pantalica Cheese Company Pty Ltd THOMASTOWN 49-65 Trawalla Avenue 20052 Lactalis Australia Pty Ltd ECHUCA FACTORY 2 Denmark Road Licensee No. Licensee details Suburb 20055 Regal Cream Products Pty Ltd COLAC Bulla Dairy Foods 43-49 Connor Street 20057 Tatura Milk Industries Ltd TATURA Tatura Milk Industries Pty Ltd 236 Hogan Street 20066 Warrnambool Cheese & Butter Factory Company ALLANSFORD Holdings Ltd 5330-5331 Great Ocean Road 20068 Marca Trinacria Pty Ltd HEIDELBERG WEST 32 Kylta Road 20070 Yea Brand Pty Ltd YEA Yea Brand Dairy 10 Melaleuca Street 20073 Lactalis Jindi Pty Ltd JINDIVICK Jindi Cheese Old Telegraph Road 20086 Monde Nissin (Australia) Pty Ltd CLAYTON Black Swan Foods 532-534 Clayton Road 20099 Lactalis Australia Pty Ltd BENDIGO 93 Bannister Street 20100 Lactalis Australia Pty Ltd ROWVILLE 842 Wellington Road 20108 BDD Milk Pty Ltd CHELSEA HEIGHTS 150 Wells Road 20111 Jalna Dairy Foods Pty Ltd THOMASTOWN 31 Commercial Drive Licensee No. -

Aip News National Food Waste December 2018 Strategy Halving Australia’S Food Waste by 2030

AIP NEWS NATIONAL FOOD WASTE DECEMBER 2018 STRATEGY HALVING AUSTRALIA’S FOOD WASTE BY 2030 November 2017 AIP NATIONAL TECHNICAL FORUM MARK THIS DATE MOVING ALONGSIDE IN YOUR DIARY 2019 PACKAGINGNational Food Waste Strategy INNOVATION & DESIGN AWARDS TUESDAY 30 APRIL 2019 SOFITEL WENTWORTH, SYDNEY, NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA ith 2018 nearing an end it is time to reflect on what was one of the most successful and action- packed year the Australian Institute of Packaging (AIP) has ever had in its 55 year history. We started the year by hosting the 2018 AIP National Conference, 2018 Packaging Innovation & Design Awards, 2018 WorldStar Packaging Awards, the 100th World Packaging Organisation WBoard Meeting and the inaugural Women in Industry Forum and we just kept going for the rest of the year. We have tried to highlight some of the key events and initiatives that the AIP undertook this year in this our final newsletter for 2018. Please don’t forget the submissions are now open for the 2019 Australasian Packaging Innovation & Design Awards and the 2019 Scholarships; we encourage all of you to enter as many categories as you can. Our Awards program is the exclusive entry point for the prestigious international WorldStar Packaging Awards for Australia and New Zealand. I would also like to remind you that the biennial AIP National Technical Forum is now moving to be held on the same day as the annual Packaging Innovation & Design (PIDA) Awards and will be designed to focus on showcasing best-practice and award-winning Save Food & Sustainable Packaging Designs and Innovative packaging across Food, Beverage, Pharmaceutical and Domestic Household. -

Public Competition Assessment 31 January 2005 Fonterra Co

Public Competition Assessment 31 January 2005 Fonterra Co-operative Ltd’s proposed acquisition of National Foods Ltd The Australian Competition and Consumer ACCC (‘ACCC’) announced on 18 January 2005 that it would not intervene in the proposed acquisition by Fonterra Co-operative Ltd (‘Fonterra’) of all the shares in National Foods Ltd (‘NFL’) after accepting court-enforceable undertakings pursuant to s87B of the Trade Practices Act 1974, which require Fonterra to divest certain assets upon achieving control of NFL. The ACCC made its decision on the basis of information provided by the parties and from information arising from market inquiries. The parties The Acquirer – Fonterra Co-operative Limited (Fonterra) Fonterra is a New Zealand co-operative owned by more than 12,000 New Zealand dairy farmers and as a substantial exporter of dairy products is one of the top ten dairy companies in the world. It exports close to 95% of New Zealand’s dairy production and is responsible for almost 40% of international dairy trade. Fonterra is also a leading manufacturer of consumer dairy products in Australia. Those products include ice-cream, butter, cheese, cream, yoghurt and dairy desserts and, to a more limited extent, fresh and flavoured milk in Western Australia. Fonterra’s product portfolio also includes processed meats and convenience foods. Fonterra participates in the dairy industry in Australia through a wholly owned subsidiary, PB Foods, which owns the “Peters” and “Brownes” brands in Western Australia. Fonterra also owns Bonland Dairies as well as part of Bonlac. PB Foods Peters & Brownes or PB Foods is based in Western Australia and has a long-established history of producing quality dairy products in Australia for the Australian and overseas markets. -

HC Determination

Heritage Council Registrations and Reviews Committee Petersville Factory Administration Building (H2394) 254–294 Wellington Road, Mulgrave, City of Monash Hearing – 17 September 2019 Members – Ms Lucinda Peterson (Chair), Ms Louise Honman, Prof Andrew May DETERMINATION OF THE HERITAGE COUNCIL Inclusion in the Victorian Heritage Register – After considering the Executive Director’s recommendation, all submissions received, and conducting a hearing into the matter, the Heritage Council has determined, pursuant to section 49(1)(a) of the Heritage Act 2017, that the Petersville Factory Administration Building located at 254– 294 Wellington Road, Mulgrave is of State-level cultural heritage significance and is to be included as a Registered Place in the Victorian Heritage Register. Lucinda Peterson (Chair) Louise Honman Andrew May Decision Date – 13 December 2019 13 December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT As a peak Heritage body, the Heritage Council is proud to acknowledge the Traditional Owners as the original custodians of the land and waters on which we meet, and to acknowledge the importance and significance of Aboriginal cultural heritage in Victoria. We honour Elders past and present whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. HEARING PARTICIPANTS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, HERITAGE VICTORIA (‘THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’) Submissions were received from the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria (‘the Executive Director’). Ms Clare Chandler, Heritage Officer – Assessments, and Mr Geoff Austin, Manager - Heritage Register and Permits, appeared and made verbal submissions on behalf of the Executive Director. CIP ALZ (WELLINGTON ROAD) PTY LTD (‘THE OWNER’) Submissions were received from King & Wood Mallesons on behalf of CIP ALZ (Wellington Road) Pty Ltd, the owner of the Petersville Factory Administration Building located at 254–294 Wellington Road, Mulgrave (‘the Place’). -

Collection Name

PETERS (WA) LIMITED An American, Frederick A B Peters, formed the Peters American Delicacy Company in WA in July 1929. In 1948, it became Peters Ice Cream (WA) Limited. In 1981, an amalgamation with Peters Foods (WA) Pty Limited (successor to the Western Ice Company that was acquired by Peters in 1929) formed Peters (WA) Limited. Edward Browne started a dairy in the Shenton Park area in the late 1880s and in 1915 he purchased the Wholesale Farmers Co-op Dairy Co. and developed Brownes Dairy Ltd. This company was totally acquired by Peters in 1962 after having some co-operative ventures since 1949. The Peters and Brownes Group was taken over by Fonterra Brands (Australia (P&B) Pty. Ltd in 2005. PRIVATE ARCHIVES MANUSCRIPT NOTE (MN 2560; ACC 6851A; 8218A, 9818A, 10433A) SUMMARY OF CLASSES ADVERTISING LISTS ALBUMS MANUSCRIPT ANNUAL REPORTS MEMORANDA APPLICATIONS MINUTE BOOK ARTICLES NEWSLETTERS BIOGRAPHIES NEWSPAPER CUTTINGS CALENDARS PACKAGING CATALOGUE PHOTOGRAPHS CORRESPONDENCE POSTERS DIARIES PRICE LISTS DRAFTS PRINTING PLATE EXTRACTS PUBLICATIONS FILES RECORD BOOKS FINANCIAL INFORMATION REPORTS HISTORIES STOCK SALES INDUCTION KITS SCRAP BOOKS INSURANCE POLICIES SHARE REGISTERS INVITATIONS SIGNS LEAFLETS SOUND RECORDINGS LEDGERS STICKERS LEGAL DOCUMENTS TRIBUTES Acc. No. DESCRIPTION ADVERTISING 6851A/50 n.d. OSM Collection of wall and freezer posters, and promotional material for Peters ice cream products. 31 items MN 2560 1 Acc. No. DESCRIPTION 6851A/51 n.d. Collection of wall and freezer posters for Pauls ice cream products. Also a promotional file given to retailers for the new “Alf” ice cream. 25 items 6851A/52 Date range: 1950s? - 1976 OSM Brownes. -

Douglas Dc-6 & Dc-6B in Australian Service (Part 2

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN AVIATION MUSEUM SIGNIFICANT AIRCRAFT PROFILES DOUGLAS DC-6 & DC-6B IN AUSTRALIAN SERVICE (PART 2) Introduction The Douglas DC-6 was introduced to Australian domestic routes in December 1953 in the livery of ANA (Australian National Airways). This brief history outlines the aircraft’s selection, service life and involvement of Sir Ivan Holyman, co-founder and chief executive of ANA. Part 1 of this series tells the story of the DC-6’s introduction to Australian international services with British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines in 1948. Pre-WWII Background In 1854, William Holyman arrived in northern Tasmania where he settled following a voyage from England. There he established a small coastal shipping company that over the following decades expanded considerably. Agreements with shipping companies Union Steamship Company of New Zealand and Huddart Parker & Co of Melbourne in 1902-1904 saw Holyman vessels operating to Adelaide and Melbourne. As the 20th Century dawned, so had a third generation of the Holyman family, most of whom were employed in the family shipping business. The advent of WWI would eventually lead two members of this generation into the realm of aviation. Victor Holyman trained and qualified as a Royal Naval Air Service pilot, serving in France and as a test pilot in England, before returning to Australia and rejoining Holyman as a sea captain. His younger brother Ivan (born in 1896) served throughout the war from Gallipoli to France. Entering as a private, rising to captain, he was wounded four times and awarded the Military Cross. On his return to Tasmania and Holyman, he shared his brother’s interest in aviation though never learnt to fly.