'Toward a Modern Reasoned Approach to the Doctrine of Restraint of Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOLUME 7 No. 7 July 2014 ISSN 1835-7628 DIARY July Saturday

VOLUME 7 No. 7 July 2014 ISSN 1835-7628 FROM THE EDITOR ed. There is too, something from the event that must lift Australian pride - the faith, trust and peaceful enjoyment. Jim Boyce, our President, has spent some time in hospital Where else in the world does the first Minister attend a in the past week. We all wish him the very best and a public event where it was hard to identify the presence of speedy recovery. escort or security? As you will surely have noticed, Jim is a major contributor Warringah Australia Remembers, held under peerless blue to our newsletters and his absence creates a substantial sky, the Sun so bright the cheeks cried out for relief whilst gap. There is no President’s Report this month and there the body rejoiced in the near summer warming. We will not be a monthly meeting during July. would not have had it otherwise; idyllic for this annual outdoor event that the media and wider public let slip. Thank you to the authors of the various articles in this There are few opportunities to take the children of today issue - Keith Amos, George Champion, Shelagh Champion, to glimpse the world of long ago, when peace in our time Rose Cullen and Jim (I had two of his articles in the was the goal of our leaders. pipeline). I welcome all contributions - small or large - so please send them in. The service, held on Friday 30 May, commemorated Syd- As has been mentioned previously, there is a lot of work ney becoming a target for attack by enemy forces in a (and expense) in producing and mailing hard copies of the world that was yet to come to terms with the futility of Newsletter. -

Chillout an Oxford Cold Storage Publication

Chillout An Oxford Cold Storage publication Issue 18 – December 2013 Message from Management In this issue : Paul Fleiszig Message from Management New Activities and skills Transport & Training reports Achievements Welcome to the 2013 Oxford newsletter. This year has been O H & S Hatched and Matched another successful year for the Oxford Logistics Group. We have all Years of Service, and more ! met many challenges and taken a number of opportunities. This newsletter will cover some of the commercial and personal highlights for our ‘Oxford family’ for the year. 2013 has seen Oxford grow again. We completed our 13B extension in October on budget and with minimal delay. The new store holds about 23,000 pallets in two rooms. The 13B complex is built using the latest energy saving & operating technology. The key new feature is the implementation of mobile racking. This is a first for Oxford. The implementation gave us many challenges, which our engineering & IT teams in conjunction with our builders Vaughan Construction and racking providers & contractors Dematic, Storax, Barpro & One Stop Shelving overcame brilliantly. More details regarding the mobile racking & the other new features built into our new store can be found within this newsletter. We commenced 2013 with storage at capacity. We struggled to handle the storage volumes our customers wanted us to hold for them. Our Store Management and Staff managed the ‘over capacity’ issues extremely well. We maintained high levels of service for all our customers in very difficult circumstances. It is a credit to the professionalism & dedication of all our staff. We ran most of our stores at near capacity for a large part of the year. -

Definition of Consideration

Weekly Information Sheet 06 Consideration Definition of Contract: “An agreement between two or more parties creating obligations that are enforceable or otherwise recognizable at law.” Elements of a Contract include: • Agreement, • Between Competent Parties, • Based on Genuine Assent, • Supported by Consideration, • for Lawful Purpose Subject Matter, • in Legal Form. Definition of Consideration: “Something (such as an act, a forbearance or a return promise) bargained for and received by a promisor from a promise, that motivates a person to do something.” It’s a “Bargained-for-Exchange” and requires “Mutuality of Promises” Purpose and Function of Consideration: • The purpose of consideration is to distinguish between those promises that are enforceable, and those promises that are not. • Promises to make a gift are unenforceable because they lack consideration. • There are two primary functions of consideration – evidentiary and cautionary. Measure and Adequacy of Consideration: Measure of Consideration: Legal Detriment and Bargained for Exchange Adequacy of Consideration: • Amount of Consideration Considered Immaterial • Sufficiency of Consideration Not Reviewable • Exceptions – o Past Consideration, Pre-existing Legal Obligations and Moral Obligations Sham, Incidental, Unconscionable or Fraudulent Consideration o Forbearance, Illusory and Conditional Promises Consideration Forbearance – Positive Consideration and Forbearance Consideration Illusory Promises – Not Consideration because not a Promise Bilateral Contracts - To be enforceable, there must be mutuality of obligation. Conditional Promises: Depends on the occurrence of a future specified condition in order for the promise to be binding. Such promises are enforceable. Exceptions: • Charitable Subscriptions - A charity’s reliance on the pledge, will be a substitute for consideration • Uniform Commercial Code - In some situations, UCC abolishes the requirement of consideration. -

Breach of Employment Contracts: Restraints of Trade and The

BACKGROUND CASE UPDATE 23 May 2019 HT is a security technology company, which provides “offensive security technology” to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Its BREACH OF software is designed to access data on target devices, including hacking mobile phones or EMPLOYMENT computers, to monitor “terrorist and/or criminal” communications. CONTRACTS: One such software was the “Remote Control RESTRAINTS OF System” (“RCS”), which allowed secret access to data on target devices, without the user’s knowledge. The version at the material time was TRADE AND THE named “Galileo”. IMPORTANCE OF Woon was a former employee of HT, and had been employed as a security specialist. In January PROVING 2015, he resigned from HT and joined another company (“ReaQta”) which developed and sold DAMAGES defensive software that allowed users to detect HT SRL v Wee Shuo Woon [2019] SGHC 96 and prevent intrusive threats. This defensive software was named “ReaQta-Core”. SUMMARY HT commenced proceedings against Woon, and The Plaintiff (“HT”) sued a former employee alleged that he had breached his employment (“Woon”) for breach of his employment contract, contract by engaging in ReaQta’s business while and breach of an implied duty of good faith and still employed by HT. It further alleged that Woon fidelity. HT alleged that while Woon was still breached a non-compete clause which prohibited employed by HT, he breached Clauses 10(a) and him from being employed by a competitor within 12 10(b) of his employment contract and his implied months after termination of his employment. duty of good faith and fidelity by engaging in the business of a competitor without HT’s consent. -

DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition

Dairy Industry Association of Australia DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition 2017 Results DUCT C ODUCT C RO ROM OM P P P P Y Y E E R T IR I T I I A A T T D D I I O O N N N N A A 2 2 I I 0 0 R R 1 1 O O 7 7 T T C C I I V V R E L D V GO SIL RESULTS – 2017 Results Booklet 2017 DIAA Victorian Dairy Product Competition n n Butter ................................................................................. 4 n n Cheese ............................................................................... 5 n n Dips ...................................................................................11 n n Powder .............................................................................11 n n Yoghurt ............................................................................12 n n Milk ...................................................................................15 n n Cream ...............................................................................18 n n Dairy desserts ................................................................19 n n Innovation ......................................................................19 n n Ice-cream, gelati, frozen yoghurt ...........................19 n n Non-bovine product ...................................................23 n n Organic products .........................................................24 n n Other ................................................................................24 The DIAA thanks its National Partners DIAA VICTORIAN DAIRY PRODUCT COMPETITION INDUSTRY-SPONSORED -

Contracts—Restraint of Trade Or Competition in Trade—Forum-Selection Clauses & Non-Compete Agreements: Choice-Of-Law

CONTRACTS—RESTRAINT OF TRADE OR COMPETITION IN TRADE—FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES & NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS: CHOICE-OF-LAW AND FORUM-SELECTION CLAUSES PROVE UNSUCCESSFUL AGAINST NORTH DAKOTA’S LONGSTANDING BAN ON NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., 2017 ND 288, 904 N.W.2d 34 (2017) ABSTRACT North Dakota’s prohibition on trade restriction has been described by the North Dakota Supreme Court as “one of the oldest and most continuous ap- plications of public policy in contract law.” In a unanimous decision, the court upheld North Dakota’s longstanding public policy against non-compete agreements by refusing to enforce an employment contract’s choice-of-law and form-selection provisions. In Osborne v. Brown & Saenger, Inc., the court held: (1) as a matter of first impression, dismissal for improper venue on the basis of a forum-selection clause is reviewed de novo; (2) employment contract’s choice-of-law and forum-selection clause was unenforceable to the extent the provision would allow employers to circumvent North Dakota’s strong prohibition on non-compete agreements; and (3) the non-competition clause in the employment contract was unenforceable. This case is not only significant to North Dakota legal practitioners, but to anyone contracting with someone who lives and works in North Dakota. This decision affirms the state’s enduring ban of non-compete agreements while shutting the door on contracting around the issue through forum-selection provisions. 180 NORTH DAKOTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. 95:1 I. FACTS ............................................................................................ 180 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND .............................................................. 182 A. BROAD HISTORY OF NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS ................ 182 B. -

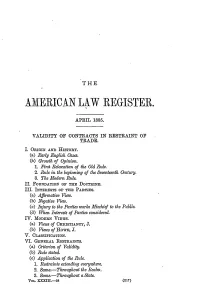

Validity of Contracts in Restraint of Trade

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. APRIL 1885. VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS IN RESTRAINT OF TRADE. I. ORIGIN AND HISTORY. (a) Early English Cases. (b) Growth of Opinion. 1. First Relaxation of the Old Rule. 2. Rule in the beginning of the Seventeenth Century. 3. The Modern Rule. II. FOUNDATION OF THE DOCTRINE. III. INTERESTS OF THE PARTIES. (a) Affrmative View. (b) Negative View. (c) Injury to the Partiesworks Mischief to the Public. (d) When Interests of Parties considered. IV. MODERN VIEWS. (a) Views of CHRISTIANCY, J. (b) Views of HowE, J. V. CLASSIFICATION. 'U. GENERAL RESTRAINTS. (a) Griterionof Validity. (b) Rule stated. (c) Application of the Rule. 1. Restraints extending everywhere. 2. 8ame.-Throughout the Realm. 3. Same.-Throughout a State. VoL. XXXII.-28 (217) VALIDITY OF CONTRACTS 4. Same.-Throughout a large portion of a State or Country. 5. Same.-Commerce upon the High Seas. 6. Same.- Confined to Locality, but sulect to Covenantees selection. 7. 1ime. 8. Restraints removable at Option of Party bound. (d) Exceptions to the Rule. I.Classification of Exceptions. ii. Exceptions considered. 1. Where the Vendee requires the Protection secured by the Restraint. (a) Scope of the Principle. (b) Cases where applied. 2. Restraints to put an end to ruinous Competition. 3. Where the Benefits secured by the Contract are lfutual. (a) Agreements of Joint-Inventors.' (b) To secure Benefits of an Invention. (c) To Labor exclusively for a particularPerson.. 4. Contracts to protect Patents, Trade-Marks and Secret Processes of Manufacture. 5. Where Business Restrained is contrary to the Policy of the Law. VII. PARTIAL RESTRAINTS. -

Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions John F

Marquette Law Review Volume 17 Article 9 Issue 3 April 1933 Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions John F. Savage Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation John F. Savage, Employment Contracts - Restraint of Trade - Injunctions, 17 Marq. L. Rev. 230 (1933). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol17/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW he has a contract and that he has acquired contract rights. It were better public policy to prohibit entirely the issuance of such contracts. * * * I suggest that the matter may well receive the serious consideration of the legislature." VINCENT T. HARTNETT EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS-RESTRAINT OF TRADE-INJUNCTIONS. - Defendant had been employed as driver of the plaintiff's wagon, collecting and delivering towels on one of the plaintiff's routes for eleven years. In 1930 he was made route foreman, and thereupon he entered into a contract with the plaintiff whereby the latter agreed to pay him a stated wage, and the defendant agreed that he would not within two years after leaving plaintiff's employ in any way carry on a similar business with the plaintiff's customers. The contract could be terminated by either party by a two weeks' notice. In 1932 the defendant was discharged. -

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery Chs 55 Peters Foods Pty Ltd Collection

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 55 PETERS FOODS PTY LTD COLLECTION Ice Cream, Launceston Food Production Establishments, Launceston INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.Record Books 2.Minutes of Meetings 3.Correspondence 4.Publications 5.Newspaper Cuttings 6.Sample Books, Product Wrappers 7.Miscellaneous Records 8.Ephemera OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION Peters Ice Cream (Vic.), which commenced operations in Melbourne in 1929, began distributing its products in Tasmania in 1932. Distribution was undertaken by Johnstone & Wilmot Pty Ltd until 1947, when Peters’ York Street premises took over. Later the York Street building became Peters frozen foods store. Airfreight from Victoria replaced sea transport in 1949. Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) Pty Ltd, a subsidiary company of Peters Ice Cream (Vic.), was established in 1954 to conduct Peters operations in Tasmania. The company built a factory on a 12 acre site at 89- 99 Talbot Road, Launceston (previously an apple orchard) and on 11 July 1955 the factory made its first ice cream in Tasmania. Full production began in June 1956. Several houses were built on the property for key staff. Set in landscaped grounds, the factory became a popular tourist attraction. In Peters Ice Cream (Vic.) Ltd 1962 annual report it was noted that the manufacture and distribution of crumpets had started on an experimental basis in Launceston as an added line for winter months. That year Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) acquired the Tasmanian Ice Cream Co. Pty Ltd. By 1964 Peters Ice Cream (Tas.) had depots in Hobart, Devonport, Burnie, Ulverstone, Queenstown and St Marys. In addition to making ice cream, the company marketed products from the northwest coast under the Birdseye, Farmer Ed and Hy. -

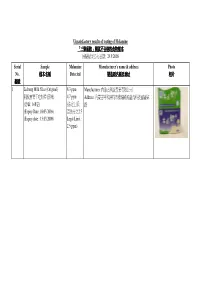

List of Food Samples for Testing of Melamine IO 29.9.2008 V3

Unsatisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試不合格的食物樣本」測試不合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Melamine Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 Detected 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 1 Licheng Milk Slice (Original) 8.3 ppm Manufacturer: 內蒙古利誠實業有限公司 利誠實業干吃奶片(原味) 4.7 ppm Address: 內蒙古呼和浩特市機塲路鴻盛高科技園區緯二 (淨重: 168 克) (法定上限: 路 (Expiry Date: 10.03.2009) 百萬分之2.5 (Expiry date : 13.03.2009) Legal Limit : 2.5 ppm) Satisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試合格的食物樣本」測試合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 1 Meiji Hohoemi Milkpowder Cube (Net Weight: Manufacturer: Meiji Dairies Corporation 108 g) Address: 1-2-10, Shinsuna, Koto-ku, Tokyo (Expiry date : 21.6.2009) 明治乳業株式會社KS 東京都江東區新砂1-2-10 2 Icero Follow Momo Milk Powder Above 9 Month Manufacturer: Icero Co., Ltd. (Net Weight: 900 g) Address: 16-23, Minato 4-Shibaura, Minato-ku, (Expiry date : 14.10.2009) Tokyo, Japan 3 Gerber Graduates Finger Foods Biter Biscuits Manufacturer: Gerber Products Company (Net weight 5 oz (142g)) Address: Fremont, MI 49413, USA (Expiry date : 25.4.2010) Satisfactory results of testing of Melamine 「「「三聚氰胺「三聚氰胺」」」測試合格的食物樣本」測試合格的食物樣本 抽驗結果公布日期: 29.9.2008 Serial Sample Manufacturer’s name & address Photo No. 樣本名稱 製造商名稱及地址 相片 編號 4 Heinz Smooth Strawberry Yoghurt Dessert (110g Manufacturer: H.J. Heinz Company Australia Limited Net) Address: 105 Camberwell Road, Hawthorn East, Victoria 3123 (All ages from 6 months) Australia (Expiry date : 24.3.2010) 5 Kameda Haihain (Weight 53g) Manufacturer: Kameda Seika Company Limited (Expiry date : 22.12.2008) Address: 3-1-1 Kamedakogyodanch Konan Nigata Nigata, Japan Product of Japan 6 Takara Animal Mate Biscuits (Net Weight 340g) Manufacturer: Takara Confectionery Co., Ltd. -

Tradestaff & Co. V. Nogiec, 77 Va. Cir. 77 (Chesapeake 2008)

Positive As of: June 10, 2014 7:25 PM EDT TradeStaff & Co. v. Nogiec Circuit Court of the City of Chesapeake, Virginia September 4, 2008, Decided Case No. CL08-1512 Reporter: 77 Va. Cir. 77; 2008 Va. Cir. LEXIS 226 TradeStaff & Co., d/b/a 1800SKILLED.com v. outside the statute of frauds and need not be in Seth Nogiec, Chipton Ross, Inc., and C. A. writing. The court also found that the Jones, Inc. non-compete agreement was overly broad and would not be enforced by the court. The court Core Terms reasoned that although the employer had a legitimate business interest in keeping its demurrer, non-compete, restrictive covenant, customer lists and relationships intact, the conspiracy, geographic, covenants, statute of non-compete agreement was unlimited in both frauds, allegations, termination, conspire, its geographic and functional scope. Next, the contractual relationship, former employee, court found that the employer did not allege that common law conspiracy, unenforceable, any of its customers had breached their contracts enforceable, tortious interference, overly broad, with the employer due to the actions of customers, serviced, parties, pleaded, cause of defendants, nor had they asserted a decrease in action, provides, legitimate business, former revenue. Finally, the court found that parties employer, particularity, competitive, indirectly, could not conspire to violate an unenforceable functions, alleged conspiracy contract because to do so would not be a criminal or unlawful purpose. Case Summary Outcome Procedural Posture The demurrer was sustained as to Count I with Plaintiff former employer filed suit against prejudice. The demurrer was sustained as to defendants, former employee and a competitor, Counts II, III, IV, and V; however counsel was alleging five causes of action including (I) granted leave to amend within thirty days. -

Non-Compete Clauses: Protection Or Restraint?

Non-compete clauses: protection or restraint? Back to Corporate and M&A Law Committee publications Alipak Banerjee Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Saumy Ramakrishnan Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Yashasvi Tripathi Nishith Desai Associates, New Delhi [email protected] Imagine: Before the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, Company B, a private limited company, acquired Company A, another private company, with both companies incorporated in India. John Doe was the promoter of Company A, and as part of the acquisition, he signed up to a non-compete obli- gation that does not permit him to start a new business, or to take up employment, consultancy or enter into any other engagement with any entity competing with the business of Company A. His association with Company B and the non-compete restriction is contractually valid until December 2021. However, in the present times, as part of austerity measures, he has been asked to discontinue his services. Due to the pandemic, the market has become volatile and jobs are difficult to come by. Now, he has received an offer from a competing entity. John Doe is in a dilemma: he needs to take up the offer with the competitor, as his skills and expertise are limited to this sector; however, the possibility of Company B pursuing legal action against him for breach of contract is troubling him. What does non-compete mean? Non-compete clauses are standard in employment agreements, especially with senior executives, and also in M&A deals. Through non-compete clauses, founders and key executives exiting the business are bound by certain restrictions.