Thioesterase Induction by 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-P-Dioxin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

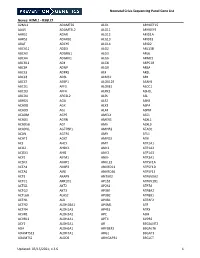

Targeted Genes and Methodology Details for Neuromuscular Genetic Panels

Targeted Genes and Methodology Details for Neuromuscular Genetic Panels Reference transcripts based on build GRCh37 (hg19) interrogated by Neuromuscular Genetic Panels Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and/or Sanger sequencing is performed Motor Neuron Disease Panel to test for the presence of a mutation in these genes. Gene GenBank Accession Number Regions of homology, high GC-rich content, and repetitive sequences may ALS2 NM_020919 not provide accurate sequence. Therefore, all reported alterations detected ANG NM_001145 by NGS are confirmed by an independent reference method based on laboratory developed criteria. However, this does not rule out the possibility CHMP2B NM_014043 of a false-negative result in these regions. ERBB4 NM_005235 Sanger sequencing is used to confirm alterations detected by NGS when FIG4 NM_014845 appropriate.(Unpublished Mayo method) FUS NM_004960 HNRNPA1 NM_031157 OPTN NM_021980 PFN1 NM_005022 SETX NM_015046 SIGMAR1 NM_005866 SOD1 NM_000454 SQSTM1 NM_003900 TARDBP NM_007375 UBQLN2 NM_013444 VAPB NM_004738 VCP NM_007126 ©2018 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research Page 1 of 14 MC4091-83rev1018 Muscular Dystrophy Panel Muscular Dystrophy Panel Gene GenBank Accession Number Gene GenBank Accession Number ACTA1 NM_001100 LMNA NM_170707 ANO5 NM_213599 LPIN1 NM_145693 B3GALNT2 NM_152490 MATR3 NM_199189 B4GAT1 NM_006876 MYH2 NM_017534 BAG3 NM_004281 MYH7 NM_000257 BIN1 NM_139343 MYOT NM_006790 BVES NM_007073 NEB NM_004543 CAPN3 NM_000070 PLEC NM_000445 CAV3 NM_033337 POMGNT1 NM_017739 CAVIN1 NM_012232 POMGNT2 -

Small Cell Ovarian Carcinoma: Genomic Stability and Responsiveness to Therapeutics

Gamwell et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2013, 8:33 http://www.ojrd.com/content/8/1/33 RESEARCH Open Access Small cell ovarian carcinoma: genomic stability and responsiveness to therapeutics Lisa F Gamwell1,2, Karen Gambaro3, Maria Merziotis2, Colleen Crane2, Suzanna L Arcand4, Valerie Bourada1,2, Christopher Davis2, Jeremy A Squire6, David G Huntsman7,8, Patricia N Tonin3,4,5 and Barbara C Vanderhyden1,2* Abstract Background: The biology of small cell ovarian carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT), which is a rare and aggressive form of ovarian cancer, is poorly understood. Tumourigenicity, in vitro growth characteristics, genetic and genomic anomalies, and sensitivity to standard and novel chemotherapeutic treatments were investigated in the unique SCCOHT cell line, BIN-67, to provide further insight in the biology of this rare type of ovarian cancer. Method: The tumourigenic potential of BIN-67 cells was determined and the tumours formed in a xenograft model was compared to human SCCOHT. DNA sequencing, spectral karyotyping and high density SNP array analysis was performed. The sensitivity of the BIN-67 cells to standard chemotherapeutic agents and to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and the JX-594 vaccinia virus was tested. Results: BIN-67 cells were capable of forming spheroids in hanging drop cultures. When xenografted into immunodeficient mice, BIN-67 cells developed into tumours that reflected the hypercalcemia and histology of human SCCOHT, notably intense expression of WT-1 and vimentin, and lack of expression of inhibin. Somatic mutations in TP53 and the most common activating mutations in KRAS and BRAF were not found in BIN-67 cells by DNA sequencing. -

ACAT) in Cholesterol Metabolism: from Its Discovery to Clinical Trials and the Genomics Era

H OH metabolites OH Review Acyl-Coenzyme A: Cholesterol Acyltransferase (ACAT) in Cholesterol Metabolism: From Its Discovery to Clinical Trials and the Genomics Era Qimin Hai and Jonathan D. Smith * Department of Cardiovascular & Metabolic Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-216-444-2248 Abstract: The purification and cloning of the acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) enzymes and the sterol O-acyltransferase (SOAT) genes has opened new areas of interest in cholesterol metabolism given their profound effects on foam cell biology and intestinal lipid absorption. The generation of mouse models deficient in Soat1 or Soat2 confirmed the importance of their gene products on cholesterol esterification and lipoprotein physiology. Although these studies supported clinical trials which used non-selective ACAT inhibitors, these trials did not report benefits, and one showed an increased risk. Early genetic studies have implicated common variants in both genes with human traits, including lipoprotein levels, coronary artery disease, and Alzheimer’s disease; however, modern genome-wide association studies have not replicated these associations. In contrast, the common SOAT1 variants are most reproducibly associated with testosterone levels. Keywords: cholesterol esterification; atherosclerosis; ACAT; SOAT; inhibitors; clinical trial Citation: Hai, Q.; Smith, J.D. Acyl-Coenzyme A: Cholesterol Acyltransferase (ACAT) in Cholesterol Metabolism: From Its 1. Introduction Discovery to Clinical Trials and the The acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT; EC 2.3.1.26) enzyme family Genomics Era. Metabolites 2021, 11, consists of membrane-spanning proteins, which are primarily located in the endoplasmic 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ reticulum [1]. -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

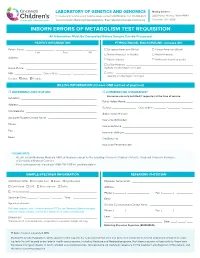

Inborn Errors of Metabolism Test Requisition

LABORATORY OF GENETICS AND GENOMICS Mailing Address: For local courier service and/or inquiries, please contact 513-636-4474 • Fax: 513-636-4373 3333 Burnet Avenue, Room R1042 www.cincinnatichildrens.org/moleculargenetics • Email: [email protected] Cincinnati, OH 45229 INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM TEST REQUISITION All Information Must Be Completed Before Sample Can Be Processed PATIENT INFORMATION ETHNIC/RACIAL BACKGROUND (Choose All) Patient Name: ___________________ , ___________________ , ________ European American (White) African-American (Black) Last First MI Native American or Alaskan Asian-American Address: ____________________________________________________ Pacific Islander Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry ____________________________________________________ Latino-Hispanic _____________________________________________ Home Phone: ________________________________________________ (specify country/region of origin) MR# __________________ Date of Birth ________ / ________ / _______ Other ____________________________________________________ (specify country/region of origin) Gender: Male Female BILLING INFORMATION (Choose ONE method of payment) o REFERRING INSTITUTION o COMMERCIAL INSURANCE* Insurance can only be billed if requested at the time of service. Institution: ____________________________________________________ Policy Holder Name: _____________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________ Gender: ________________ Date of Birth ________ / ________ / _______ -

Deciphering the Gene Expression Profile of Peroxisome Proliferator

Chen et al. J Transl Med (2016) 14:157 DOI 10.1186/s12967-016-0871-3 Journal of Translational Medicine RESEARCH Open Access Deciphering the gene expression profile of peroxisome proliferator‑activated receptor signaling pathway in the left atria of patients with mitral regurgitation Mien‑Cheng Chen1*, Jen‑Ping Chang2, Yu‑Sheng Lin3, Kuo‑Li Pan3, Wan‑Chun Ho1, Wen‑Hao Liu1, Tzu‑Hao Chang4, Yao‑Kuang Huang5, Chih‑Yuan Fang1 and Chien‑Jen Chen1 Abstract Background: Differentially expressed genes in the left atria of mitral regurgitation (MR) pigs have been linked to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway in the KEGG pathway. However, specific genes of the PPAR signaling pathway in the left atria of MR patients have never been explored. Methods: This study enrolled 15 MR patients with heart failure, 7 patients with aortic valve disease and heart failure, and 6 normal controls. We used PCR assay (84 genes) for PPAR pathway and quantitative RT-PCR to study specific genes of the PPAR pathway in the left atria. Results: Gene expression profiling analysis through PCR assay identified 23 genes to be differentially expressed in the left atria of MR patients compared to normal controls. The expressions of APOA1, ACADM, FABP3, ETFDH, ECH1, CPT1B, CPT2, SLC27A6, ACAA2, SMARCD3, SORBS1, EHHADH, SLC27A1, PPARGC1B, PPARA and CPT1A were significantly up-regulated, whereas the expression of PLTP was significantly down-regulated in the MR patients compared to normal controls. The expressions of HMGCS2, ACADM, FABP3, MLYCD, ECH1, ACAA2, EHHADH, CPT1A and PLTP were significantly up-regulated in the MR patients compared to patients with aortic valve disease. -

Functional Significance of the Two ACOX1 Isoforms and Their

Laboratory Investigation (2010) 90, 696–708 & 2010 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/10 $32.00 Functional significance of the two ACOX1 isoforms and their crosstalks with PPARa and RXRa Aurore Vluggens1,2,3, Pierre Andreoletti1,2, Navin Viswakarma3, Yuzhi Jia3, Kojiro Matsumoto3, Wim Kulik4, Mushfiquddin Khan5, Jiansheng Huang3, Dongsheng Guo3, Sangtao Yu3, Joy Sarkar3, Inderjit Singh5, M Sambasiva Rao3, Ronald J Wanders4, Janardan K Reddy3 and Mustapha Cherkaoui-Malki1,2 Disruption of the peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acox1) gene in the mouse results in the development of severe microvesicular hepatic steatosis and sustained activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-a (PPARa). These mice manifest spontaneous massive peroxisome proliferation in regenerating hepatocytes and eventually develop hepatocellular carcinomas. Human ACOX1, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the peroxisomal b-oxidation pathway, has two isoforms including ACOX1a and ACOX1b, transcribed from a single gene. As ACOX1a shows reduced activity toward palmitoyl-CoA as compared with ACOX1b, we used adenovirally driven ACOX1a and ACOX1b to investigate their efficacy in the reversal of hepatic phenotype in Acox1(À/À) mice. In this study, we show that human ACOX1b is markedly effective in reversing the ACOX1 null phenotype in the mouse. In addition, expression of human ACOX1b was found to restore the production of nervonic (24:1) acid and had a negative impact on the recruitment of coactivators to the PPARa-response unit, which suggests that nervonic acid might well be an endogenous PPARa antagonist, with nervonoyl-CoA probably being the active form of nervonic acid. In contrast, restoration of docosahexaenoic (22:6) acid level, a retinoid-X-receptor (RXRa) agonist, was dependent on the concomitant hepatic expression of both ACOX1a and ACOX1b isoforms. -

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

DYSREGULATION of LONG-CHAIN ACYL-Coa SYNTHETASES in CANCER and THEIR TARGETING STRATEGIES in ANTICANCER THERAPY Md Amir Hossain1, Jun Ma2, Yong Yang1 1

Hossain et al RJLBPCS 2020 www.rjlbpcs.com Life Science Informatics Publications Original Review Article DOI: 10.26479/2020.0603.06 DYSREGULATION OF LONG-CHAIN ACYL-CoA SYNTHETASES IN CANCER AND THEIR TARGETING STRATEGIES IN ANTICANCER THERAPY Md Amir Hossain1, Jun Ma2, Yong Yang1 1. Academic Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China. 2. Ningxia Baoshihua Hospital, Ningxia, China. ABSTRACT: Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, and the number of cases globally continues to increase. Cancer is caused by certain changes in genes that are involved in controlling cell functions and cell division. Notably, metabolic dysregulation is one the hallmarks of cancer, and increases in fatty acid metabolism have been demonstrated to promote the growth and survival of a variety of cancers. In human, fatty acids either can be breakdown into acetyl-CoA through catabolic metabolism and aid in ATP generation or in the anabolic metabolism they can incorporate into triacylglycerol and phospholipid. Importantly, both of these pathways need activation of fatty acids, and the key players in this activation of fatty acids are the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSLs) that are commonly dysregulated in cancer and associated with oncogenesis and survival. Therefore, it provides a rationale to target ACSLs in cancer. This review summarizes the current understanding of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases in cancer and their targeting opportunities. KEYWORDS: Acyl-CoA synthetases, cancer, fatty acid, lipid metabolism. Article History: Received: April 15, 2020; Revised: May 10, 2020; Accepted: May 30, 2020. Corresponding Author: Prof. Yong Yang* Academic Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China. -

High Throughput Computational Mouse Genetic Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.01.278465; this version posted January 22, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. High Throughput Computational Mouse Genetic Analysis Ahmed Arslan1+, Yuan Guan1+, Zhuoqing Fang1, Xinyu Chen1, Robin Donaldson2&, Wan Zhu, Madeline Ford1, Manhong Wu, Ming Zheng1, David L. Dill2* and Gary Peltz1* 1Department of Anesthesia, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; and 2Department of Computer Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA +These authors contributed equally to this paper & Current Address: Ecree Durham, NC 27701 *Address correspondence to: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.01.278465; this version posted January 22, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Background: Genetic factors affecting multiple biomedical traits in mice have been identified when GWAS data that measured responses in panels of inbred mouse strains was analyzed using haplotype-based computational genetic mapping (HBCGM). Although this method was previously used to analyze one dataset at a time; but now, a vast amount of mouse phenotypic data is now publicly available, which could lead to many more genetic discoveries. Results: HBCGM and a whole genome SNP map covering 53 inbred strains was used to analyze 8462 publicly available datasets of biomedical responses (1.52M individual datapoints) measured in panels of inbred mouse strains. As proof of concept, causative genetic factors affecting susceptibility for eye, metabolic and infectious diseases were identified when structured automated methods were used to analyze the output. -

Inflammatory Stimuli Induce Acyl-Coa Thioesterase 7 and Remodeling of Phospholipids Containing Unsaturated Long (C20)-Acyl Chains in Macrophages

Supplemental Material can be found at: http://www.jlr.org/content/suppl/2017/04/17/jlr.M076489.DC1 .html Inflammatory stimuli induce acyl-CoA thioesterase 7 and remodeling of phospholipids containing unsaturated long (C20)-acyl chains in macrophages Valerie Z. Wall,*,† Shelley Barnhart,* Farah Kramer,* Jenny E. Kanter,* Anuradha Vivekanandan-Giri,§ Subramaniam Pennathur,§ Chiara Bolego,** Jessica M. Ellis,§§,*** Miguel A. Gijón,††† Michael J. Wolfgang,*** and Karin E. Bornfeldt1,*,† Department of Medicine,* Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Nutrition, and Department of Pathology,† UW Medicine Diabetes Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Department of Internal Medicine,§ University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences,** University of Padova, Padova, Italy; Department of Nutrition Science,§§ Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN; Department of Biological Chemistry,*** Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; and Department of Pharmacology,††† University of Downloaded from Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO Abstract Acyl-CoA thioesterase 7 (ACOT7) is an intracel- containing unsaturated long (C20)-acyl chains in macro- lular enzyme that converts acyl-CoAs to FFAs. ACOT7 is in- phages, and, although ACOT7 has preferential thioesterase duced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS); thus, we investigated activity toward these lipid species, loss of ACOT7 has no ma- www.jlr.org downstream effects of LPS-induced induction of ACOT7 jor detrimental effect on macrophage inflammatory pheno- and its role in inflammatory settings in myeloid cells. Enzy- types.—Wall, V. Z., S. Barnhart, F. Kramer, J. E. Kanter, matic thioesterase activity assays in WT and ACOT7-deficient A. Vivekanandan-Giri, S. Pennathur, C. Bolego, J. M. Ellis, macrophage lysates indicated that endogenous ACOT7 con- M.