John Marshall Harlan and the Constitutional Rights of Negroes: the Transformation of a Southerner*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE CALL of the ROLL Iilaho.-Henry C

<tongrrssional1Rcrord· United States PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 85th CONGRESS,. SECOND SESSION of America SENATE CALL OF THE ROLL Iilaho.-Henry C. Dworshak and Mr. MANSFIELD. I suggest the ab Frank Church. Illinois.-Paul H. Douglas and Everett TUESDAY, JANUARY 7, 1958 sence of a quorum. The VICE PRESIDENT. The Secre McKinley Dirksen. The 7th day of January being the day tary will call the roll. Indiana.-Homer E. Capehart and prescribed by Public Law 290, 85th The Chief Clerk <Emery L. Frazier) William E. Jenner. Congress, 1st session, for the m-eeting of <mlled the roll, and the following Sena· I owa.-Bourke B. Hiekenlooper and the 2d session of the 85th Congress, the Thos. E. Martin. tors answered to their names: Kansas.-Andrew F. Scboeppel and Senate assembled in its Chamber at the Aiken Goldwater Morse Capitol · Allott Gore Mundt Frank Carlson. RICHARD .M. NIXON, of California, Anderson Green Murray Kentucky.-John s. c ·ooper and Barrett Hayden Neely Thruston B. Morton. Vice President of the United States, Beall .Hennings Neuberger called the Senate to order at 12 o•clock 13ennett Hicken1ooper O'Mahoney Louisiana.-Allen J. Ellender and meridian. .Bible Hill Pastore Russell B. Long. .Bricker Holla;nd Payne Maine.-Margaret Chase Smith and The Chaplain, Rev. Frederick Brown Bush Hruska. Potter Harris, D. D., of the city of Washington, Butler .Humphrey Proxmire Frederick G. Payne. offered the following prayer; 13yrd Ives Purtell Maryland.-John Marshall Butler and Capehart Jackson Revercomb J. Glenn Beall. Our Father God, in the stillness of Carlson Javits Robertson Carroll Jenner Russell Massachusetts.-Leverett Saltonstall this hushed moment, in this solemn hour Oase, s. -

Harlan Record No. 55, Fall 2019

NO. 55 www.harlanfamily.org Fall 2019 SHE TOOK A WAGON BUT WE TOOK A BUS CUZ AIN’T GOT TIME FOR THAT This haiku describes very briefly what took place in late June of this year in Missouri. Here’s the rest of the story! William J. and Dora Adams “On Wednesday morning, September 13, Harlan 1899, with sad hearts we bade farewell to a host of between 1929 and 1953 friends and our dear old home in the northeast have enjoyed an unusual closeness throughout their corner of Randolph County, the Eden of Missouri.” lives, despite being geographically scattered. From her death bed in November of 1957, Dora exacted a This was the opening line penned by my promise from her children that they would carry on great-grandmother, at the age of 20, in a journal she the tradition of annual family reunions. kept during an eleven-day covered wagon trip with Her children not only kept their promise but her parents, siblings, and the family dog, as they kept actual records of the ensuing reunions! Their relocated to what she described as “the Land of son William M. Harlan (1 Oct 1910 - 23 Mar 1995) Promise” in southern Missouri’s Howell County. kept detailed documentation showing the family The journal has been passed down through held reunions annually between 1958 and 1985, generations of Harlans. Its author, Dora Anna nearly all of them in Salisbury. Though locations Adams (22 Nov 1878 - 20 Nov 1957), would marry changed and a few years were skipped after 1985, William J. -

Justice Sherman Minton and the Protection of Minority Rights, 34 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 34 | Issue 1 Article 6 Winter 1-1-1977 Justice Sherman Minton And The rP otection Of Minority Rights David N. Atkinson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation David N. Atkinson, Justice Sherman Minton And The Protection Of Minority Rights, 34 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 97 (1977), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol34/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE SHERMAN MINTON AND THE PROTECTION OF MINORITY RIGHTS* DAVID N. ATKINSON** Discrimination in education, in housing, and in employment brought cases before the Vinson Court which were often resolved by a nearly unanimous vote, but they frequently raised constitutional and institutional dilemmas of agonizing dimensions. A fundamental commitment of the Court at this time was accurately reflected by Justice Jackson's off-the-Court admonition to his colleagues on the inadvisability of seizing "the initiative in shaping the policy of the law, either by constitutional interpretation or by statutory construc- tion."' There were strong voices within the Vinson Court which held rigorously to Justice Holmes' dictum that "judges do and must legis- late, but they can do so only interstitially; they are confined from molar to molecular motions." Institutional caution, theoretically at * This is the fifth and final of a series of articles written by Professor Atkinson dealing with the Supreme Court career of Justice Sherman Minton. -

DID the FIRST JUSTICE HARLAN HAVE a BLACK BROTHER? James W

Western New England Law Review Volume 15 15 (1993) Article 1 Issue 2 1-1-1993 DID THE FIRST JUSTICE HARLAN HAVE A BLACK BROTHER? James W. Gordon Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation James W. Gordon, DID THE FIRST JUSTICE HARLAN HAVE A BLACK BROTHER?, 15 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 159 (1993), http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview/vol15/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Review & Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western New England Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 15 Issue 2 WESTERN NEW ENGLAND 1993 LAW REVIEW DID THE FIRST JUSTICE HARLAN HAVE A BLACK BROTHER? JAMES W. GORDON· INTRODUCTION On September 18, 1848, James Harlan, father of future Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, appeared in the Franklin County Court for the purpose of freeing his mulatto slave, Robert Harlan.! This appearance formalized Robert's free status and exposed a re • Professor of Law, Western New England College School of Law; J.D., University of Kentucky, 1974; Ph.D., University of Kentucky, 1981; B.A., University of Louisville, 1971. The author wishes to thank Howard I. Kalodner, Dean of Western New England College School of Law, for supporting this project with a summer research grant. The author also wishes to thank Catherine Jones, Stephanie Levin, Donald Korobkin, and Arthur Wolf for their detailed critiques and helpful comments on earlier drafts of this Article. -

The Honorable John Marshall Butler United States Senate Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce Washington 25, D

The Honorable John Marshall Butler United States Senate Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce Washington 25, D. C. Dear Senator Butler: This will acknowledge receipt of your letter of June 24, 1957 enclosing a copy of a letter received by you from Mr. L. P. Hubbard of Baltimore, Maryland. Mr. Hubbard suggests that corporations be required to make available to a central committee of its stockholders a list of all stockholders in order that they may arrange regional meetings to discuss matters of common interest and to send delegates to a national committee with instructions to attend annual meetings and vote their proxies for them. As you know some of the States have laws which require corporations to make a list of stockholders available for inspection by stockholders. Rule X-14A-7 of the Commission’s proxy rules under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 requires listed companies which intend to solicit proxies either to furnish stockholders, upon request, a reasonably current list of stockholders or to mail for such stockholders any proxy material which they may wish to transmit to other stockholders. In some cases, corporations will elect to mail the material in lieu of furnishing a list of stockholders and in other cases they will elect to turn over to the stockholders a list of stockholders. In addition to the above requirement, Rule X-14A-8 of the proxy rules requires an issuer to include in its proxy material proposals which are proper matters for stockholder action and which a stockholder wishes to submit to a vote of his fellow stockholders. -

The Attorney General's Ninth Annual Report to Congress Pursuant to The

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S NINTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AND THIRD ANNUALREPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVEDCIVIL RIGHTS CRIMES REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2016 March 1, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is the ninth annual Report (Report) submitted to Congress pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007 (Till Act or Act), 1 as well as the third Report submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (Reauthorization Act). 2 This Report includes information about the Department of Justice's (Department) activities in the time period since the eighth Till Act Report, and second Reauthorization Report, which was dated June 2019. Section I of this Report summarizes the historical efforts of the Department to prosecute cases involving racial violence and describes the genesis of its Cold Case Int~~ative. It also provides an overview ofthe factual and legal challenges that federal prosecutors face in their "efforts to secure justice in unsolved Civil Rights-era homicides. Section II ofthe Report presents the progress made since the last Report. It includes a chart ofthe progress made on cases reported under the initial Till Act and under the Reauthorization Act. Section III of the Report provides a brief overview of the cases the Department has closed or referred for preliminary investigation since its last Report. Case closing memoranda written by Department attorneys are available on the Department's website: https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-division-emmett till-act-cold-ca e-clo ing-memoranda. -

The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 28 Number 2 Symposium on Civility and Judicial Ethics in the 1990s: Professionalism in the pp.583-646 Practice of Law Symposium on Civility and Judicial Ethics in the 1990s: Professionalism in the Practice of Law The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility Edward McGlynn Gaffney Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward McGlynn Gaffney Jr., The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility, 28 Val. U. L. Rev. 583 (1994). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol28/iss2/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Gaffney: The Importance of Dissent and the Imperative of Judicial Civility THE IMPORTANCE OF DISSENT AND THE IMPERATIVE OF JUDICIAL CIVILITY EDWARD McGLYNN GAFFNEY, JR.* A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the errorinto which the dissentingjudge believes the court to have been betrayed... Independence does not mean cantankerousness and ajudge may be a strongjudge without being an impossibleperson. Nothing is more distressing on any bench than the exhibition of a captious, impatient, querulous spirit.' Charles Evans Hughes I. INTRODUCTION Charles Evans Hughes served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1910 to 1916 and as Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. -

Daniel D. Pratt: Senator and Commissioner

Daniel D. Pratt: Senator and Commissioner Joseph E. Holliday* The election of Daniel D. Pratt, of Logansport, to the United States Senate in January, 1869, to succeed Thomas A. Hendricks had come after a bitter internal struggle within the ranks of the Republican members of the Indiana General Assembly. The struggle was precipitated by James Hughes, of Bloomington, who hoped to win the honor, but it also uncovered a personal feud between Lieutenant Governor Will E. Cumback, an early favorite for the seat, and Governor Conrad Baker. Personal rivalries threatened party harmony, and after several caucuses were unable to reach an agreement, Pratt was presented as a compromise candidate. He had been his party’s nominee for a Senate seat in 1863, but the Republicans were then the minority party in the legislature. With a majority in 1869, however, the Republicans were able to carry his election. Pratt’s reputation in the state was not based upon office-holding ; he had held no important state office, and his only legislative experience before he went to Washington in 1869 was service in two terms of the general assembly. It was his character, his leadership in the legal profession in northern Indiana, and his loyal service as a campaigner that earned for him the esteem of many in his party. Daniel D. Pratt‘s experience in the United States Senate began with the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant in March, 1869. Presiding over the Senate was Schuyler Colfax, another Hoosier, who had just been inaugurated vice-president of the United States. During the administration of President Andrew Johnson, the government had been subjected to severe stress and strain between the legislative and executive branches. -

A University Microfilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2020 No. 181 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, October 23, 2020, at 11:30 a.m. Senate THURSDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2020 (Legislative day of Monday, October 19, 2020) The Senate met at 12 noon, on the ex- man, of Ohio, to be United States Dis- haven’t made the same tough decisions piration of the recess, and was called to trict Judge for the Southern District of and weren’t ready before the pandemic. order by the President pro tempore Ohio. Now Democrats want Iowans’ Federal (Mr. GRASSLEY). The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mrs. tax money to bail out irresponsible FISCHER). The President pro tempore. f State governments and somehow this Mr. GRASSLEY. Madam President, I is worth holding up relief for strug- PRAYER ask to speak for 1 minute as in morn- gling families. Come on. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- ing business. I yield the floor. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without fered the following prayer: RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY LEADER objection, it is so ordered. Let us pray. The PRESIDING OFFICER. The ma- FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY Lord of Heaven’s Army, we find our jority leader is recognized. Mr. GRASSLEY. Madam President, joy from trusting You. Today we are what we have seen over the last week ELECTION SECURITY trusting Your promise to supply all our are attempts to get COVID relief up Mr. -

Badges of Slavery : the Struggle Between Civil Rights and Federalism During Reconstruction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction. Vanessa Hahn Lierley 1981- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lierley, Vanessa Hahn 1981-, "Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 831. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/831 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Liedey B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Lierley B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Benjamin Harrison Jasmine Farrier ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband Pete Lierley who always showed me support throughout the pursuit of my Master's degree. -

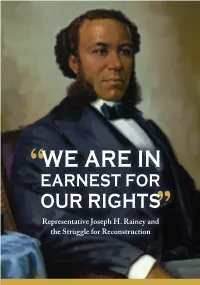

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill.