'THE @UFC and THIRD WAVE FEMINISM? WHO WOULDA THOUGHT?': GENDER, FIGHTERS, and FRAMING on TWITTER by ALLYSON QUINNEY B.A., T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

Brian Sandoval Governor STATE OF

Bruce Breslow Brian Sandoval STATE OF NEVADA Department Director Governor DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY ATHLETIC COMMISSION Bob Bennett Executive Director Chairman: Anthony A. Marnell III Members: Francisco V. Aguilar, Skip Avansino, Pat Lundvall, Michon Martin TO THE COMMISSION AND THE PUBLIC: AGENDA A duly authorized meeting of the Nevada State Athletic Commission will be held on Wednesday, February 17, 2016, at 9:00 a.m. at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Room 4500 Las Vegas, NV 89101. 1. Call to order. 2. Roll Call. 3. Public Comment. 4. Approval of the minutes of the meetings of December 17, 2015 and February 4, 2016 for possible action. 5. Adoption of the agenda for this meeting, for possible action. 6. Disclosures per NRS 281/281A. OLD BUSINESS: 1. Re‐hearing on appropriate discipline against mixed martial artist Wanderlei Silva, for possible action. CONSENT AGENDA: a. Date Requests 1. Request by Roy Englebrecht Promotions for the date of March 12, 2016 to promote a boxing event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on CBS Sports Network with a maximum of 7 fights and pending Executive Director Bob Bennett’s approval of the venue’s outdoor facilities, for possible action. 2. Request by World Series of Fighting for the date of April 2, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on NBC Sports Network, for possible action. 3. Request by Zuffa, LLC for the date of April 23, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas to be televised on PPV, for possible action. -

Political Views an Unjust Reason to Cancel

Page 8 FORUM Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Political views an unjust reason to cancel Today’s and criticism to Disney and Reporter, a source from Generation contributed to recent debates Lucasfilms said, “They have Hallie Funk on “cancel culture.” been looking for a reason to fire Several celebrities, actors, her for two months, and today and political figures have been was the final straw.” The “final Last October, actress Gina involved in these series of straw” was when Carano posted Carano stepped onto the “cancelling,” including Ellen a tweet that compared Jewish Disney+ screen as Cara Dune, DeGeneres, J.K. Rowling, and people in the Holocaust to the new female lead of the Johnny Depp. An individual is Republicans in America’s current hit show, The Mandalorian. typically “canceled” when the political climate. Although this As the season started, many public or media disagrees with is an extreme comparison that praised her acting abilities and a certain decision or belief the is not truly accurate, it is not accepted Carano as the perfect person has and chooses to stop a fireable offense. Her general cast for the role. She brought supporting them. It can be a point was not inappropriate, body positivity to the screen, result of accusations, negative but the Holocaust comparison and portrayed women as strong media coverage, or social media was. Which brings to question, and independent. But as of last posts, as in Carano’s case. are inappropriate comparisons month, she will no longer be a The controversy began back fireable offenses? part of Disney or her employing in November when Carano In June 2018, Pedro Pascal, agency. -

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Match Results

Match Results Date: 4/19/2014 Venue/Location: Amway Center -- Orlando, FL Promoter: UFC Commissioners Judge: Richard Bertrand Referee: John McCarthy Physician: Dr. Adam Brunson Commissioners Judge: Chris Lee Referee: Jorge Alonso Physician: Dr. George Panagakos Dr. Mark Williams, Chairman Judge: Jean Warring Referee: Jorge Ortiz Knockdown Timekeeper: Dr. Wayne Kearney Judge: Eliseo Rodriguez Referee: Herb Dean Alternate Referee Mr. Antonius DeSisto Judge: Hector Gomez Referee: Commissioners Present: Mr. Marco Lopez Judge: Tim Vannatta Referee: Mr. Tirso Martinez Judge: Derek Cleary Referee: Referee: Executive Director: Cynthia Hefren Asst. Executive Director: Frank Gentile Timekeeper(s): James Chittenden; Roy Silbert Event Type: MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Participants Federal ID Hometown Weight DOB Sch Rds Results Officials Suspensions and Remarks Claim form, knee, indefinite susp, neruo Referee: John McCarthy; Jack May 110-622 Costa Mesa, CA 252.5 lbs 4/14/1981 clearance 3 Judges: Jean Warring; Chris 1 Winner TKO 4:23 1st Lee; Richard Bertrand Referee stoppage from strikes Derrick Lewis 116-645 Houston, TX 256.0 lbs 2/7/1985 Rd Referee: Jorge Ortiz; Judges: Chas Skelly 101-842 Keller, TX 145.0 lbs 5/11/1985 2 3 Eliseo Rodriguez; Tim Winner by Majority Vannatta; Richard Green Suspension 180 days or Facial CT Marsid Bektic 105-060 Coconut Creek, FL 146.0 lbs 2/11/1991 Decision clearance Referee: Jorge Alonso; Ray Borg 127-020 Albuquerqu, NM 125.5 lbs 8/4/1993 3 3 Judges: Chris Lee; Hector Winner by Split Gomez; Derek Cleary Dustin Ortiz 121-691 -

The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Abysmal Brute, by Jack London This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Abysmal Brute Author: Jack London Illustrator: Gordon Grant Release Date: November 12, 2017 [EBook #55948] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ABYSMAL BRUTE *** Produced by Jeroen Hellingman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net/ for Project Gutenberg (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) THE ABYSMAL BRUTE Original Frontispiece. Original Title Page. THE ABYSMAL BRUTE BY JACK LONDON Author of “The Call of the Wild,” “The Sea Wolf,” “Smoke Bellew,” “The Night Born,” etc. NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1913 Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. Copyright, 1911, by STREET & SMITH. New York Published, May, 1913 THE ABYSMAL BRUTE I Sam Stubener ran through his mail carelessly and rapidly. As became a manager of prize-fighters, he was accustomed to a various and bizarre correspondence. Every crank, sport, near sport, and reformer seemed to have ideas to impart to him. From dire threats against his life to milder threats, such as pushing in the front of his face, from rabbit-foot fetishes to lucky horse-shoes, from dinky jerkwater bids to the quarter-of-a-million-dollar offers of irresponsible nobodies, he knew the whole run of the surprise portion of his mail. -

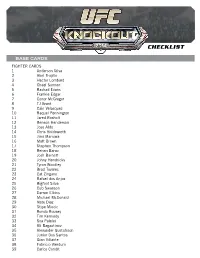

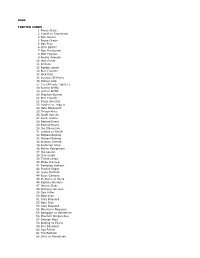

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 [email protected] PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype After a five-month hiatus, the legendary promotion Pancrase sets off the summer fireworks with a stellar mixed martial card. Studio Coast plays host to 8 main card bouts, 3 preliminary match ups, and 12 bouts in the continuation of the 2020 Neo Blood Tournament heats on July 24th in the first event since February. Reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, Isao Kobayashi headlines the main event in a non-title bout against Akira Okada who drops down from Featherweight to meet him. The Never Quit gym ace and Bellator veteran, Kobayashi is a former Pancrase Lightweight Champion. The ripped and powerful Okada has a tough welcome to the Featherweight division, but possesses notoriously frightening physical power. “Isao” the reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, has been unstoppable in nearly three years. He claimed the interim title by way of disqualification due to a grounded knee at Pancrase 295, and following orbital surgery and recovery, he went on to capture the undisputed King of Pancrase belt from Nazareno Malagarie at Pancrase 305 in May 2019. Known to fans simply as “Akira”, he is widely feared as one of the hardest hitting Pancrase Lightweights, and steps away from his 5th ranked spot in the bracket to face Kobayashi. The 33-year-old has faced some of the best from around the world, and will thrive under the pressure of this bout. A change in weight class could be the test he needs right now. The co-main event sees Emiko Raika collide with Takayo Hashi in what promises to be a test of skills and experience, mixed with sheer will-to-win guts and determination. -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical REGISTRAR’S PERIODICAL, DECEMBER 15, 2011 SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 007 CONSULTING INC. Named Alberta Corporation 1634710 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Incorporated 2011 NOV 10 Registered Address: 523, Corporation Incorporated 2011 NOV 07 Registered 10333 SOUTHPORT ROAD SW, CALGARY Address: 4500, 855 - 2ND STREET S.W., CALGARY ALBERTA, T2W 3X6. No: 2016406684. ALBERTA, T2P 4K7. No: 2016347102. 0912233 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1636354 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2011 NOV 09 Registered Address: 1700, 530 Corporation Incorporated 2011 NOV 09 Registered - 8TH AVENUE S.W., CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P Address: 5224-50TH STREET, NITON JUNCTION 3S8. No: 2116402633. ALBERTA, T0E 1S0. No: 2016363547. 0923688 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1636738 ALBERTA ULC Numbered Alberta Registered 2011 NOV 01 Registered Address: BOX 1, Corporation Incorporated 2011 NOV 02 Registered SITE 21, RR1, BOWDEN ALBERTA, T0M 0K0. No: Address: 4500, 855 - 2ND STREET S.W., CALGARY 2116386059. ALBERTA, T2P 4K7. No: 2016367381. 0924508 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1636759 ALBERTA ULC Numbered Alberta Registered 2011 NOV 07 Registered Address: 1900, 736 Corporation Incorporated 2011 NOV 02 Registered - 6TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P Address: 4500, 855 - 2ND STREET S.W., CALGARY 3T7. No: 2116396538. ALBERTA, T2P 4K7. No: 2016367597. 0924556 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1637247 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2011 NOV 09 Registered Address: 1600, 205 Corporation Incorporated 2011 NOV 04 Registered - 5TH AVENUE S.W., CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P Address: 81 WEST COACH PLACE S.W., CALGARY 2V7. -

Jasmina and Frida

Lund University International Marketing and Brand Management Master Thesis June 2021 Distancing From Dirt A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting By: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Abstract Title: Distancing From Dirt: A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting Course: BUSN39: Degree Project in Global Marketing Authors: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Keywords: Identity Construction, Consumer Identity, Framing, Cancel Culture, Oatly, DisneyPlus Thesis Purpose: With this research we aim to understand the dynamics of consumers' use of cancel culture as a resource for their identity construction online. Theoretical Framework: Theories included were surrounding framing, morality, consumers as moral protagonists, purity and dirt as well as distaste and symbolic violence. These theories were selected to aid with the analysis of the empirical material and to add new insight to the concept of identity construction by negatively distancing from brands. Methodology: This study was conducted with a foundation of a relativist and social constructivist worldview. The research design used is qualitative and the netnography was conducted with an inductive approach. For the analysis, the method of content analysis was used to unfold underlying codes and patterns in the empirical material. Main Findings: This research found that consumers use cancel culture as a resource for identity construction in an online setting. By analysing the empirical material it was found that the constant use of viscous, satirical, emotional and political framing is a way for consumers to negatively distance themselves from brands and other consumers in order to build on their identities. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 10, 2012 to Sun. September 16, 2012 Monday September 10, 2012

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 10, 2012 to Sun. September 16, 2012 Monday September 10, 2012 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Nothing But Trailers IMAX - Grand Canyon Adventure - River at Risk Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So HDNet presents a half hour of Noth- Narrated by Academy Award®-winning filmmaker, actor, and noted environmentalist Robert ing But Trailers. See the best trailers, old and new in HDNet’s collection. Redford. Follow the great Colorado River as it reveals the most pressing environmental story of our time - the world’s growing shortage of fresh water. 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Hustle 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT Mickey and the team are thrust into a daring daylight heist to retrieve stolen diamonds that Hustle are hidden beneath a police station and wanted back by the owner. Mickey and the team are thrust into a daring daylight heist to retrieve stolen diamonds that are hidden beneath a police station and wanted back by the owner. 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT JAG 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Fighting Words - While respected and decorated Marine General Earl Watson has been as- Honky Tonk TV: Your Country signed to lead the joint task force charged with capturing all the remaining high-value targets This week we’ve got Lee Brice and Colt Ford. Our girl Roxy chats with JT Hodges and he in Iraq, a troubling revelation surfaces.