FINAL REPORT a Critical Review of the Current Evidence for the Use Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glycymeris Longior (Sowerby, 1832) Clam at the Southern Edge of Its Distribution (Argentine Sea) Lucas H

Gimenez et al. Helgol Mar Res (2020) 74:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s10152-020-0534-x Helgoland Marine Research ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Age and growth of Glycymeris longior (Sowerby, 1832) clam at the southern edge of its distribution (Argentine Sea) Lucas H. Gimenez1,2†, María del Socorro Doldan1,3,4*† , Paula C. Zaidman1,3,4 and Enrique M. Morsan1,3 Abstract Even though Glycymeris longior is a clam widely distributed in the SW Atlantic Ocean, little is known about its biology and life history. The present study assessed the periodicity of the internal growth increments of G. longior using thin shell sections. Each internal growth increment was composed of two alternating bands: a translucent band (light- coloured when viewed with transmitted light) and an opaque band (dark-coloured). Annual formation for each pair of bands was demonstrated. The formation of the annual growth increments was synchronous among individuals. Growth was determined from live clams collected at El Sótano, Argentine Sea (age range 29 to 69 years). Accord- ing to the growth model, G. longior grows fast during the frst 5 years of life and then growth= becomes slower in later years; individuals reached 50% and 90% of maximum size at 5 and 13 years of age, respectively. High variability was found in shell height for the frst 10 years: diferences up to 5–7 mm among individuals were registered for the frst 2 years of age, and up to 11 mm between the ages of 3 and 9 years. The growth performance index phi-prime (φ′) and the index of growth performance (P) of G. -

COMPLETE LIST of MARINE and SHORELINE SPECIES 2012-2016 BIOBLITZ VASHON ISLAND Marine Algae Sponges

COMPLETE LIST OF MARINE AND SHORELINE SPECIES 2012-2016 BIOBLITZ VASHON ISLAND List compiled by: Rayna Holtz, Jeff Adams, Maria Metler Marine algae Number Scientific name Common name Notes BB year Location 1 Laminaria saccharina sugar kelp 2013SH 2 Acrosiphonia sp. green rope 2015 M 3 Alga sp. filamentous brown algae unknown unique 2013 SH 4 Callophyllis spp. beautiful leaf seaweeds 2012 NP 5 Ceramium pacificum hairy pottery seaweed 2015 M 6 Chondracanthus exasperatus turkish towel 2012, 2013, 2014 NP, SH, CH 7 Colpomenia bullosa oyster thief 2012 NP 8 Corallinales unknown sp. crustous coralline 2012 NP 9 Costaria costata seersucker 2012, 2014, 2015 NP, CH, M 10 Cyanoebacteria sp. black slime blue-green algae 2015M 11 Desmarestia ligulata broad acid weed 2012 NP 12 Desmarestia ligulata flattened acid kelp 2015 M 13 Desmerestia aculeata (viridis) witch's hair 2012, 2015, 2016 NP, M, J 14 Endoclaydia muricata algae 2016 J 15 Enteromorpha intestinalis gutweed 2016 J 16 Fucus distichus rockweed 2014, 2016 CH, J 17 Fucus gardneri rockweed 2012, 2015 NP, M 18 Gracilaria/Gracilariopsis red spaghetti 2012, 2014, 2015 NP, CH, M 19 Hildenbrandia sp. rusty rock red algae 2013, 2015 SH, M 20 Laminaria saccharina sugar wrack kelp 2012, 2015 NP, M 21 Laminaria stechelli sugar wrack kelp 2012 NP 22 Mastocarpus papillatus Turkish washcloth 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 NP, SH, CH, M 23 Mazzaella splendens iridescent seaweed 2012, 2014 NP, CH 24 Nereocystis luetkeana bull kelp 2012, 2014 NP, CH 25 Polysiphonous spp. filamentous red 2015 M 26 Porphyra sp. nori (laver) 2012, 2013, 2015 NP, SH, M 27 Prionitis lyallii broad iodine seaweed 2015 M 28 Saccharina latissima sugar kelp 2012, 2014 NP, CH 29 Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii sea noodles 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016 NP, CH, M, J 30 Sargassum muticum sargassum 2012, 2014, 2015 NP, CH, M 31 Sparlingia pertusa red eyelet silk 2013SH 32 Ulva intestinalis sea lettuce 2014, 2015, 2016 CH, M, J 33 Ulva lactuca sea lettuce 2012-2016 ALL 34 Ulva linza flat tube sea lettuce 2015 M 35 Ulva sp. -

Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220)

Reprint as at 1 October 2017 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 (SR 1986/220) Paul Reeves, Governor-General Order in Council At Wellington this 2nd day of September 1986 Present: The Right Hon G W R Palmer presiding in Council Pursuant to section 89 of the Fisheries Act 1983, His Excellency the Governor-Gener- al, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. Contents Page 1 Title, commencement, and application 4 2 Interpretation 4 Part 1 Southland area Total prohibition 3 Total prohibitions 15 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this official reprint. Note 4 at the end of this reprint provides a list of the amendments incorporated. These regulations are administered by the Ministry for Primary Industries. 1 Fisheries (Southland and Sub-Antarctic Areas Reprinted as at Commercial Fishing) Regulations 1986 1 October 2017 Certain fishing methods prohibited 3A Certain fishing methods prohibited in defined areas 16 3AB Set net fishing prohibited in defined area from Slope Point to Sand 18 Hill Point Minimum set net mesh size 3B Minimum set net mesh size 19 3BA Minimum net mesh for queen scallop trawling 20 Set net soak times 3C Set net soak times 20 3D Restrictions on fishing in paua quota management areas 21 3E Labelling of containers for paua taken in any PAU 5 quota 21 management area 3F Marking of blue cod pots and fish holding pots [Revoked] 21 Trawling 4 Trawling prohibited -

Marine Bivalve Molluscs

Marine Bivalve Molluscs Marine Bivalve Molluscs Second Edition Elizabeth Gosling This edition first published 2015 © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd First edition published 2003 © Fishing News Books, a division of Blackwell Publishing Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

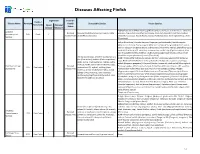

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

The Effect of Parasite Infection on Clam (Austrovenus Stutchburyi) Growth Rate and Body Condition in an Environment Modified by Commercial Harvesting

The effect of parasite infection on clam (Austrovenus stutchburyi) growth rate and body condition in an environment modified by commercial harvesting Sorrel O’Connell-Milne A thesis submitted for the degree of Masters of Science (Marine Science) University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand May 2015 iii Abstract Commercial fishing often reduces densities and changes the structure of target populations. Within these target populations, the transmission dynamics of parasites are usually strongly dependent on host densities. Because parasites have direct impacts on their host and also indirect effects on interspecific interactions and ecosystem function, harvest-induced reductions in host density can have wide repercussions. The present research investigates the effect of commercial harvesting on echinostome parasite infection within the Otago clam fishery. Clams (Austrovenus stutchburyi) have been commercially harvested from Blueskin Bay since 1983, and since 2009, experimental harvesting has extended to beds within Otago Harbour. Parasite loads (numbers of echinostome metacercariae per clam) within areas of high fishing pressure were compared to adjacent unharvested areas to assess the effects of harvesting on parasite abundance in clams. At 14 sites within Blueskin Bay and Otago Harbour, a subset of shellfish of varying age and sizes were analysed for parasite load. Unparasitised juvenile clams were also collected and caged in situ over a winter and summer period to monitor spatial and temporal patterns of parasite infection. Finally, the effect of parasite load on the growth rate of clams was monitored both in situ and in a laboratory experiment, in which juvenile clams were infected with varying levels of parasite and mortality, body condition and foot length was quantified. -

Venerupis Philippinarum)

INVESTIGATING THE COLLECTIVE EFFECT OF TWO OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ADAPTATION STRATEGIES ON JUVENILE CLAMS (VENERUPIS PHILIPPINARUM) Courtney M. Greiner A Swinomish Indian Tribal Community Contribution SWIN-CR-2017-01 September 2017 La Conner, WA 98257 Investigating the collective effect of two ocean acidification adaptation strategies on juvenile clams (Venerupis philippinarum) Courtney M. Greiner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2017 Committee: Terrie Klinger Jennifer Ruesink Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Marine and Environmental Affairs ©Copyright 2017 Courtney M. Greiner University of Washington Abstract Investigating the collective effect of two ocean acidification adaptation strategies on juvenile clams (Venerupis philippinarum) Courtney M. Greiner Chair of Supervisory Committee: Dr. Terrie Klinger School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthropogenic CO2 emissions have altered Earth’s climate system at an unprecedented rate, causing global climate change and ocean acidification. Surface ocean pH has increased by 26% since the industrial era and is predicted to increase another 100% by 2100. Additional stress from abrupt changes in carbonate chemistry in conjunction with other natural and anthropogenic impacts may push populations over critical thresholds. Bivalves are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of acidification during early life-history stages. Two substrate additives, shell hash and macrophytes, have been proposed as potential ocean acidification adaptation strategies for bivalves but there is limited research into their effectiveness. This study uses a split plot design to examine four different combinations of the two substratum treatments on juvenile Venerupis philippinarum settlement, survival, and growth and on local water chemistry at Fidalgo Bay and Skokomish Delta, Washington. -

The Ecological and Socio-Cultural Values of Estuarine Shellfisheries in Hawai`I and Aotearoa New Zealand

‘Mauka makai’ ‘Ki uta ki tai’: The ecological and socio-cultural values of estuarine shellfisheries in Hawai`i and Aotearoa New Zealand. Ani Alana Kainamu Murchie Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu ki Whangaroa, Cunningham Clan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, The University of Canterbury 2017 Abstract Estuaries rank among the most anthropogenically impacted aquatic ecosystems on earth. There is a growing consensus on anthropogenic impacts to estuarine and coastal environments, and consequently the ecological, social, and cultural values. The protection of these values is legislated for within the U.S. and Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). The respective environmental catchment philosophy ‘Mauka Makai’ and ‘Ki Uta Ki Tai’ (lit. inland to sea) of Indigenous Hawaiian and Ngāi Tahu forms the overarching principle of this study. The scientific component of this study measured shellfish population indices, condition index, tissue and sediment contamination which was compared across the landscape development index, physico-chemical gradient and management regimes. Within the socio-cultural component of this study, Indigenous and non-Indigenous local residents, ‘beach-goers’, managers, and scientists were interviewed towards their perception and experience of site and catchment environmental condition, resource abundance and changes, and management effectiveness of these systems. Both the ecological and cultural findings recognised the land as a source of anthropogenic stressors. In Kāne`ohe Bay, Hawai`i, the benthic infaunal shellfish density appears to be more impacted by anthropogenic conditions compared with the surface dwelling Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. The latter was indicative of environmental condition. Although the shellfish fishery has remained closed since the 1970s, clam densities have continued to decline. -

AEBR 114 Review of Factors Affecting the Abundance of Toheroa Paphies

Review of factors affecting the abundance of toheroa (Paphies ventricosa) New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 114 J.R. Williams, C. Sim-Smith, C. Paterson. ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-0-478-41468-4 (online) June 2013 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-resources/publications.aspx http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright - Ministry for Primary Industries TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 2. METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 3 3. TIME SERIES OF ABUNDANCE .................................................................................. 3 3.1 Northland region beaches .......................................................................................... 3 3.2 Wellington region beaches ........................................................................................ 4 3.3 Southland region beaches ......................................................................................... -

Recent Trends in Marine Phycotoxins from Australian Coastal Waters

Review Recent Trends in Marine Phycotoxins from Australian Coastal Waters Penelope Ajani 1,*, D. Tim Harwood 2 and Shauna A. Murray 1 1 Climate Change Cluster (C3), University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 2 Cawthron Institute, The Wood, Nelson 7010, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61‐02‐9514‐7325 Academic Editor: Lucio G. Costa Received: 6 December 2016; Accepted: 29 January 2017; Published: 9 February 2017 Abstract: Phycotoxins, which are produced by harmful microalgae and bioaccumulate in the marine food web, are of growing concern for Australia. These harmful algae pose a threat to ecosystem and human health, as well as constraining the progress of aquaculture, one of the fastest growing food sectors in the world. With better monitoring, advanced analytical skills and an increase in microalgal expertise, many phycotoxins have been identified in Australian coastal waters in recent years. The most concerning of these toxins are ciguatoxin, paralytic shellfish toxins, okadaic acid and domoic acid, with palytoxin and karlotoxin increasing in significance. The potential for tetrodotoxin, maitotoxin and palytoxin to contaminate seafood is also of concern, warranting future investigation. The largest and most significant toxic bloom in Tasmania in 2012 resulted in an estimated total economic loss of ~AUD$23M, indicating that there is an imperative to improve toxin and organism detection methods, clarify the toxin profiles of species of phytoplankton and carry out both intra‐ and inter‐species toxicity comparisons. Future work also includes the application of rapid, real‐time molecular assays for the detection of harmful species and toxin genes. -

Physiological Effects and Biotransformation of Paralytic

PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS AND BIOTRANSFORMATION OF PARALYTIC SHELLFISH TOXINS IN NEW ZEALAND MARINE BIVALVES ______________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Sciences in the University of Canterbury by Andrea M. Contreras 2010 Abstract Although there are no authenticated records of human illness due to PSP in New Zealand, nationwide phytoplankton and shellfish toxicity monitoring programmes have revealed that the incidence of PSP contamination and the occurrence of the toxic Alexandrium species are more common than previously realised (Mackenzie et al., 2004). A full understanding of the mechanism of uptake, accumulation and toxin dynamics of bivalves feeding on toxic algae is fundamental for improving future regulations in the shellfish toxicity monitoring program across the country. This thesis examines the effects of toxic dinoflagellates and PSP toxins on the physiology and behaviour of bivalve molluscs. This focus arose because these aspects have not been widely studied before in New Zealand. The basic hypothesis tested was that bivalve molluscs differ in their ability to metabolise PSP toxins produced by Alexandrium tamarense and are able to transform toxins and may have special mechanisms to avoid toxin uptake. To test this hypothesis, different physiological/behavioural experiments and quantification of PSP toxins in bivalves tissues were carried out on mussels ( Perna canaliculus ), clams ( Paphies donacina and Dosinia anus ), scallops ( Pecten novaezelandiae ) and oysters ( Ostrea chilensis ) from the South Island of New Zealand. Measurements of clearance rate were used to test the sensitivity of the bivalves to PSP toxins. Other studies that involved intoxication and detoxification periods were carried out on three species of bivalves ( P. -

For the Determination of Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins In

toxins Article A Comparative Analysis of Methods (LC-MS/MS, LC-MS and Rapid Test Kits) for the Determination of Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins in Oysters, Mussels and Pipis Penelope A. Ajani 1,* , Chowdhury Sarowar 2, Alison Turnbull 3 , Hazel Farrell 4, Anthony Zammit 4, Stuart Helleren 5, Gustaaf Hallegraeff 3 and Shauna A. Murray 1 1 School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, P.O. Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia; [email protected] 2 Sydney Institute of Marine Science, 19 Chowder Bay Road, Mosman, NSW 2088, Australia; [email protected] 3 Institute for Marine and Antarctic Science, University of Tasmania, 15-21 Nubeena Crescent, Taroona, TAS 7053, Australia; [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (G.H.) 4 NSW Food Authority, NSW Department of Primary Industries, P.O. Box 232, Taree, NSW 2430, Australia; [email protected] (H.F.); [email protected] (A.Z.) 5 Dalcon Environmental, Building 38, 3 Baron-Hay Ct, South Perth, WA 6151, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Rapid methods for the detection of biotoxins in shellfish can assist the seafood industry and safeguard public health. Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins (DSTs) are produced by species of the dinoflagellate genus Dinophysis, yet the comparative efficacy of their detection methods has not been systematically determined. Here, we examined DSTs in spiked and naturally contaminated shellfish– Citation: Ajani, P.A.; Sarowar, C.; Sydney Rock Oysters (Saccostrea glomerata), Pacific Oysters (Magallana gigas/Crassostrea gigas), Blue Turnbull, A.; Farrell, H.; Zammit, A.; Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Pipis (Plebidonax deltoides/Donax deltoides), using LC-MS/MS Helleren, S.; Hallegraeff, G.; Murray, and LC-MS in 4 laboratories, and 5 rapid test kits (quantitative Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent S.A.