Acadia Maritime Cultural Resources Inventory Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Minutes

Gulf of Maine Seabird Working Group nd 32 Annual Summer Meeting Hog Island, Bremen, Maine August 12, 2016 Visit the website gomswg.org 1 Table of Contents Seabird Islands – Gulf of Maine (map).............................................................................................3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................4 Island and Site Reports .....................................................................................................................4 Canada.................................................................................................................................4 Country Island.......................................................................................................4 North Brother Island..............................................................................................6 Machias Seal Island ..............................................................................................8 Maine ..................................................................................................................................10 Eastern Brothers ...................................................................................................10 Petit Manan Island ..............................................................................................................13 Ship Island ..........................................................................................................................16 -

A Range and Distribution Study of the Natural European Oyster, Ostrea Edulis, Population in Casco Bay, Maine

A RANGE AND DISTRIBUTION STUDY OF THE NATURAL EUROPEAN OYSTER, OSTREA EDULIS, POPULATION IN CASCO BAY, MAINE By C.S. HEINIG and B.P. TARBOX INTERTIDE CORPORATION SOUTH HARPSWELL, MAINE 04079 1985 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to thank Dana Wallace, recently retired from the Department of Marine Resources, for his assistance in the field and his insight. We also wish to thank Walter Welsh and Laurice Churchill of the Department of Marine Resources for their help with background information and data. Thanks also go to Peter Darling, Cook's Lobster, Foster Treworgy, Interstate Lobster, Robert Bibber and Dain and Henry Allen for allowing us the use of their wharfs, docks, and moorings. Funding for this project was provided by the State Department of Marine Resources with equipment and facilities provided by INTERTIDE CORPORATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS AND MATERIALS.................................................................................................... 2 DATA AND OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................... 3 A. Geographic Range and Distribution...................................................................................... 3 Section 1. Cape Small to Harbor Island, New Meadows River............................................ -

History of the Bar Harbor Water Company: 1873-2004

HISTORY OF THE BAR HARBOR WATER COMPANY 1873-2004 By Peter Morrison Crane & Morrison Archaeology, in association with the Abbe Museum Prepared for the National Park Service November, 2005 Frontispiece ABSTRACT In 1997, the Bar Harbor Water Company’s oldest major supply pipe froze and cracked. This pipe, the iron 12" diameter Duck Brook line was originally installed in 1884. Acadia National Park owns the land over which the pipe passes, and the company’s owner, the Town of Bar Harbor, wishes to hand over ownership of this pipe to the Park. Before this could occur, the Maine Department of Environmental Testing performed testing of the soil surrounding the pipe and found elevated lead levels attributable to leaching from the pipe’s lead joints. The Park decided that it would not accept responsibility for the pipe until the lead problem had been corrected. Because the pipe lies on Federally owned land, the Park requested a study to determine if the proposed lead abatement would affect any National Register of Historic Places eligible properties. Specifically, the Park wished to know if the Water System itself could qualify for such a listing. This request was made pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. The research will also assist the Park in meeting obligations under Section 110 of the same act. Intensive historical research detailed the development of the Bar Harbor Water Company from its inception in the wake of typhoid and scarlatina outbreaks in 1873 to the present. The water system has played a key role in the growth and success of Bar Harbor as a destination for the east coast’s wealthy elite, tourists, and as a center for biological research. -

An Environmental Bibliography of Muscongus Bay, Maine

AN ENVIRONMENTAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MUSCONGUS BAY, MAINE by Morgan King & Michele Walsh Quebec-Labrador Foundation Atlantic Center for the Environment AN ENVIRONMENTAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MUSCONGUS BAY, MAINE BY MORGAN KING & MICHELE WALSH © QUEBEC-LABRADOR FOUNDATION/ATLANTIC CENTER FOR THE E NVIRONMENT IPSWICH, MA (REVISED ED. 2008) 2008 REVISIONS AMANDA LABELLE, C OORDINATOR, MUSCONGUS BAY PROJECT 2005 EDITION RESEARCHERS MORGAN KING, INTERN, QLF MARINE PROGRAM KATHLEEN G USTAFSON, INTERN, QLF MARINE PROGRAM 2005 EDITION EDITORS MICHELE WALSH, COORDINATOR, QLF MARINE PROGRAM JENNIFER ATKINSON, DIRECTOR, QLF MARINE PROGRAM 2008 MUSCONGUS BAY PROJECT STEERING COMMITTEE CHRIS DAVIS, PEMAQUID OYSTER C OMPANY JAY ASTLE, G EORGES RIVER LAND TRUST DEBORAH C HAPMAN, C REATIVE CONSENSUS SAM CHAPMAN, WALDOBORO SHAD HATCHERY DIANE C OWAN, THE LOBSTER CONSERVANCY HEATHER DEESE, UMAINE SCHOOL OF MARINE SCIENCES SCOTT HALL, NATIONAL AUDUBON SEABIRD RESTORATION PROGRAM BETSY HAM, MAINE C OAST HERITAGE TRUST SHERMAN HOYT, UMAINE C OOPERATIVE EXTENSION, K NOX & LINCOLN COUNTIES DONNA MINNIS, PEMAQUID WATERSHED ASSOCIATION SLADE MOORE, BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION, LTD. LIZ PETRUSKA, MEOMAK VALLEY LAND TRUST AMANDA RUDY, KNOX/LINCOLN SOIL & WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT RICHARD WAHLE, BIGELOW LABORATORY FOR OCEAN SCIENCES MADE POSSIBLE THROUGH SUPPORT FROM: AMERICORPS , JESSIE B. C OX CHARITABLE TRUST, SURDNA FOUNDATION UNIVERSITY OF MAINE COOPERATIVE EXTENSION, KNOX & LINCOLN COUNTIES, AND WALLIS FOUNDATION COVER PHOTO: JOHN ATKINSON, ELIOT, ME 1 WHERE IS MUSCONGUS BAY? Muscongus Bay is located at the midpoint of Maine’s coastline between Penobscot Bay to the east and the Damariscotta River to the west. Outlined by three peninsulas supporting ten small towns (Monhegan, St. George, South Thomaston, Thomaston, Warren, Cushing, Friendship, Waldoboro, Bremen, Bristol) straddling Knox and Lincoln counties, the bay has retained much of its traditional maritime culture and heritage. -

Biological Summary of Islands Within Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife

Maine Coastal Islands NWR Biological Summary of Islands within Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge December 2018 Maine Coastal Islands NWR Maine Coastal Islands NWR Maine Coastal Islands NWR Island Summary Contents Spectacle Island ..........................................................................................................................6 Cross Island ................................................................................................................................7 Scotch Island ...............................................................................................................................9 Outer Double Head Shot Island ................................................................................................. 10 Inner Double Head Shot Island .................................................................................................. 11 Mink Island ............................................................................................................................... 12 Old Man Island ......................................................................................................................... 13 Libby Island .............................................................................................................................. 15 Stone Island & Stone Island Ledge ............................................................................................ 17 Eastern Brothers ....................................................................................................................... -

Accessibility Guide

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Accessibility Guide Table of Contents Map of Popular Park Locations 2 General Information 3 Entrance Fees Service Animals For Your Health 3 Air Quality Medical Information Physical and Mobility Resources 4 Getting Around Parking Accessible Facilities and Areas 4 Visitor Centers Beaches 5 Campgrounds Picnic Areas Stores and Restaurants Within the Park 6 Activities 6 Trails Carriage Roads Other Sites of Interest 7 Park Ranger Programs Ranger-led Boat Cruises Scenic Driving Areas 8 Resources for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing 8 Park Ranger Programs Assistive Listening Devices Park Orientation Video Resources for the Blind and Low Vision 8 Park Orientation Video Audio Tour 1 Map of Popular Park Locations 3 3 Thompson Island Information Center 102 198 Hulls Cove Visitor Center Bar Island 3 BAR HARBOR 233 Park Headquarters 233 198 Sieur de Bear Brook Picnic Area Eagle Lake Monts Somesville Nature Center 102 S O Cadillac M E Mountain S 3 Bubble Pond S 3 O U 198 N Pretty Marsh D Ikes Picnic Area Jordan Pond Point e v i Sand Beach r one way D t Thunder Hole n Jordan Pond a e g r House a S Fabbri Picnic Area Echo 102 Lake Otter Point Blackwoods Campground 102 SEAL HARBOR NORTHEAST HARBOR 3 Seal Cove SOUTHWEST HARBOR Acadia National Park Park Loop Road Accessible Carriage Roads 102 North 0 2 Kilometers 0 2 Miles 102A Seawall Campground 102A BERNARD BASS HARBOR Bass Harbor Head Light 2 General Information Entrance Fees $ U.S. -

TREMONT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN NOVEMBER 2010 Draft

TREMONT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN NOVEMBER 2010 Draft SUBMITTED TO STATE PLANNING OFFICE IN RESPONSE TO NOVEMBER 15, 2010 LETTER TREMONT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN August 2010 DRAFT FOR STATE PLANNING OFFICE REVIEW Prepared by the Tremont Comprehensive Planning Committee: Chris Eaton Mary Jones Jim Keene Kathi Thurston Reva Weisenberg With technical assistance from the Hancock County Planning Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1 PART I INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS A. Population ............................................................................................................................3 1. Purpose .......................................................................................................................3 2. Key Findings and Issues ............................................................................................3 3. Highlights of the 1997 Plan .......................................................................................3 4. Public Opinion Survey Results ..................................................................................3 5. Trends Since 1990......................................................................................................3 6. Seasonal Population ...................................................................................................5 7. Projected Population ..................................................................................................7 -

In the New England District

HISTORICAL SUMMARY OF FEDERAL NAVIGATION STUDIES AUTHORIZATIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS & FEDERAL NAVIGATION PROJECT MAINTENANCE IN THE NEW ENGLAND DISTRICT MAINE MAINE LIST OF DOCUMENTS AND REPORTS ON RIVERS AND HARBORS IN THE NEW ENGLAND DISTRICT ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER, Brunswick A-1 aka; Brunswick Harbor AROOSTOCK RIVER, Fort Fairfield to Masardis A-2 ATKINS BAY, Phippsburg A-3 BACK COVE, Portland See Also; Portland Harbor B-1 BAGADUCE RIVER, Penobscot B-7 BANGOR HARBOR, Bangor & Brewer B-10 See: Penobscot River BAR HARBOR, Bar Harbor B-15 BASIN COVE, South Harpswell (See Also POTTS HARBOR) B-22 BASS HARBOR, Tremont B-23 BASS HARBOR BAR, Tremont B-25 BEALS HARBOR, Beals (Barneys Cove) B-26 BELFAST HARBOR, Belfast B-27 BIDDEFORD POOL, Biddeford (See WOOD ISLAND HARBOR) -- BIRCH HARBOR, Gouldsboro (No File) -- BLUE HILL HARBOR, Blue Hill B-32 BOOTHBAY HARBOR, Boothbay Harbor B-33 BRUNSWICK CANAL, Brunswick & Harpswell B-36 BRUNSWICK HARBOR, Brunswick (See ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER) -- BUCK HARBOR, South Brooksville (No File) -- BUCKS HARBOR, Machiasport B-37 BUCKSPORT HARBOR, Bucksport & Verona B-39 -i- MAINE LIST OF DOCUMENTS AND REPORTS ON RIVERS AND HARBORS IN THE NEW ENGLAND DISTRICT (Continued) BUNGANUC CREEK (Maquoit Bay), Harpswell & Brunswick B-42 BUNKER HARBOR, Gouldsboro B-43 CALF ISLAND HARBOR, Roque Bluffs (Johnsons Cove) C-1 CAMDEN HARBOR, Camden C-2 CAMPOBELLO INTERNATIONAL PARK, Deer Isle, New Brunswick, Canada Mulholland Point Lighthouse - Shore Protection along Lubec Channel C-7 CAPE NEDDICK HARBOR, York C-8 CAPE NEWAGON HARBOR, Southport -

Cranberry Isles Names

— 1 — Placenames of the Cranberry Isles, Maine Henry A. Raup, Mount Desert, Maine February, 2016 The accompanying gazetteer of the placenames of the Cranberry Isles is part of a larger project that will include the placenames of Mount Desert Island. It is presented here in a preliminary form with the hope that it will be found interesting and useful. Comments, corrections, and additions will be welcome ([email protected]). Gazetteer Format. Information for each feature noted in the text follows a standard format. Below is an example of a typical entry, and a guide to the individual elements contained in each entry (where applicable). An individual name entry will not necessarily include all elements. Entry Example: Spurling Cove Cranberry Isles (*) Bay on the north shore of Great Cranberry Island, east of Spurling Point at the present town landing. (44°15’29”N, 68°16’07”W). Common (Rand 1893; USGS 1942a, 1956a; NOAA 1978, 1979; BHT 8/11/1983, p. 2; 7/14/1987, p. B20). Origin: Surname of nearby resident (Fernald 1890b). More specifically, for Capt. Benjamin Spurling (Spurling, T. 1979; Smart 2010, p. 11). Variants: Spurlings Cove. Rare (Fernald 1890b; Komusin 2012). Sperlin Cove. Rare (Colby and Stuart 1887). Sperlins Cove. Occasional former use (USCS 1872; Colby 1881). Cranberry Cove. Rare (BHT 8/27/1987, p. B32). BGN decision: (BGN 1933, p. 716). Listing Elements: [A] Feature Name [B] Town (*) [C] Type of Feature. [D] (Elevation). [E] Location. [F] (Coordinates). [G] Usage Frequency. [H] Use citations; typically including the earliest recorded use followed by other examples of use. -

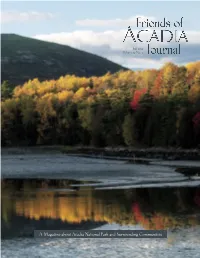

Fall 2014 Volume 19 No

Fall 2014 Volume 19 No. 2 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities Friends of Acadia Journal Fall 2014 1 PURCHASE YOUR PARK PASS! Whether driving, walking, bicycling, or riding the Island Explorer through the park, we all must pay the entrance fee. Eighty percent of all fees paid in Acadia stay in Acadia, to be used for projects that directly benefit park visitors and resources. The Acadia National Park $20 weekly pass and $40 annual pass are available seasonally at the following locations: Sand Beach Entrance Station Hulls Cove Visitor Center Bar Harbor Village Green Thompson Island Information Center Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds Acadia weekly passes are also available seasonally at: Cadillac Mountain Gift Shop Jordan Pond Gift Shop Some area businesses; call 207-288-3338 for an up-to-date list of locations For more information visit www.friendsofacadia.org President’s Message AcAdiA’s ExcEllEncE t the Friends of Acadia Annual Meet- remarkable relationship with the surround- ing in mid-July, Acadia National ing local communities. Acadia’s boundary APark Superintendent Sheridan Steele weaves in and out of more than a dozen shared the impressive news that Acadia had small fishing harbors, historic villages, recently earned top honors in a USA Today summer colonies, bustling sea-ports, tour- poll that asked readers to choose the best ist destinations, and offshore islands. This national park in the country. Just a few days porous, crooked boundary and Acadia’s re- later, we learned that Good Morning America lationships with its countless neighbors are conducted another poll in which Acadia complex—as is the charge to manage natu- again emerged on top—not only among ral and cultural resources across the check- national parks, but as “America’s Favorite er-board ownership—but ultimately, they Place.” We should not have been surprised are a large part of what makes the Acadia when the New York Times followed with its experience so rewarding and memorable. -

GSM B 01.Pdf

\ Stratigraphy and geology of the Bar Harbor Formation, Frenchman Bay, Maine WILLIAM J. METZGER Department of Geology, State University College, Fredonia, New York 14063 ABSTRACT The Bar Harbor Formation consists of more than 2000 feet of typically well-bedded, feldspathic siltstones and sand stones displaying well-developed graded bedding. These units were probably deposited by turbidity currents in relatively deep, quiet water. A minimum of 450 feet of boulder-bearing polymictic conglomerate constitutes the base of the section which rests unconformably on a previously undescribed green stone. Clasts found in the conglomerate are composed pri marily of the underlying greenstone, several types of acidic volcanic rocks, and quartz. 'I'he sequence of rock uni ts ex posed in Frenchman Bay is 1. Ellsworth Schist (oldest), 2. greenstone, 3. Bar Harbor Formation (youngest). The Bar Harbor Formation was intruded first by diorite in the form of sills and later by granitic plutons. l',) INTRODUCTION This paper outlines the relationships between the Bar Harbor Formation and adjacent geological units in the area of Frenchman Bay, Maine. The nature of the Bar Harbor sec tion, including a thick, basal, polymictic conglomerate, is described. The field evidence used to establish the rela tive age relationships among the several geologic units is critically reviewed. Finally, a possible environment of deposition is suggested for the Bar Harbor Formation. The name Bar Harbor Series was applied by Shaler (1889) to the bedded sedimentary sequence which crops out on the northern and northeastern shore of Mount Desert Island. Although Shaler was careful to point out that no evidence for the age of these rocks was known, he indicated that there were similarities between some of the stratified rocks on Mt. -

Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1989

Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1989 Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals 1989 Editor & Production Director SHERRY L. VERRILL Contributing Editor DIANE M. HOPKINS TABLE OF CONTENTS Index by Town 3 South Coast 4-8 Western Lakes and Mountains 9-17 Kennebec Valley/Moose River Valley 18-22 M id Coast 23-31 Acadia 3 2 -40 Sunrise County 4 1 -45 Katahdin/Moosehead 4 6 -52 Aroostook 53 Index of Advertisers 54-56 A PUBLICATION OF THE MAINE PUBLICITY BUREAU, INC. 97 Winthrop Street, Hallowell, Maine 04347 (207) 289-2423 THE MAINE PUBLICITY BUREAU, INC. A Private Non-Profit Corporation for the Promotion o f Maine’s Tourism Industry January 1989 Dear Friends of Maine: The State of Maine offers ideal opportunities for vacation, relaxation, and recreation, thanks in part to its wide variety of splendid accommo dations carefully designed to fulfill every individual desire. To assist with these many special needs, the Maine Publicity Bureau publishes a number of detailed publications in which the prospective Maine visitor can find information about hotels, motels, inns, sporting camps, restaurants, gift shops, as well as the countless other businesses catering to travelers. You’re presently reading from the “Maine Guide to Camp & Cottage Rentals”. This booklet is devoted, in its entirety, to listings of rental properties having housekeeping facilities. We would like to be able to tell you that we personally have inspected every property listed herein prior to publishing this booklet. Unfortu nately, however, this is not practical. For this reason, we’re obliged to inform our readers that we have urged our advertisers to be accurate and truthful in describing their properties.