Udupi Hoteliers in Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Disaster Management Plan- Udupi

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN- UDUPI UDUPI DISTRICT 2015-16 -1- -2- Executive Summary The District Disaster Management Plan is a key part of an emergency management. It will play a significant role to address the unexpected disasters that occur in the district effectively. The information available in DDMP is valuable in terms of its use during disaster. Based on the history of various disasters that occur in the district, the plan has been so designed as an action plan rather than a resource book. Utmost attention has been paid to make it handy, precise rather than bulky one. This plan has been prepared which is based on the guidelines from the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM). While preparing this plan, most of the issues, relevant to crisis management, have been carefully dealt with. During the time of disaster there will be a delay before outside help arrives. At first, self-help is essential and depends on a prepared community which is alert and informed. Efforts have been made to collect and develop this plan to make it more applicable and effective to handle any type of disaster. The DDMP developed touch upon some significant issues like Incident Command System (ICS), In fact, the response mechanism, an important part of the plan is designed with the ICS. It is obvious that the ICS, a good model of crisis management has been included in the response part for the first time. It has been the most significant tool for the response manager to deal with the crisis within the limited period and to make optimum use of the available resources. -

612 Natural History Notes

612 NATURAL HISTORY NOTES ruber and Rhinella crucifer (Souza-Júnior et al. 1991. Rev. Brasil. Biol. 51:585–588). The specimens of G. chabaudi (males) identi- fied herein possess the diagnostic characters of this species, es- pecially three pairs of genital papillae: one preanal pair, another postanal, laterally projecting and a third ventral pair located in a short, subulated and coiled tail. In this note, the distribution of G. chabaudi is expanded and P. platensis is a new host record. We are grateful to Marissa Fabrezi (Instituto de Biología y Geociencias del NOA-Salta) for identifying the tadpoles. GABRIEL CASTILLO, Universidad Nacional de San Juan Argentina. Di- versidad y Biología de Vertebrados del Árido, Departamento de Biología, San Juan, Argentina (e-mail: [email protected]); GERALDINE RA- MALLO, Instituto de Invertebrados, Fundación Miguel Lillo, San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina (e-mail: [email protected]); CHARLES R. BURSEY, Pennsylvania State University, Department of Biology, Shenango Campus, Sharon, Pennsylvania 16146, USA (e-mail: [email protected]); STE- PHEN R. GOLDBERG, Whittier College, Department of Biology, Whittier, California 90608, USA (e-mail: [email protected]); JUAN CARLOS ACOSTA, Universidad Nacional de San Juan Argentina. Diversidad y Bi- ología de Vertebrados del Árido, Departamento de Biología, San Juan, Ar- gentina (e-mail: [email protected]). PSEUDOPHILAUTUS AMBOLI (Amboli Bush Frog). PREDA- TION BY TERRESTRIAL BEETLE LARVAE. Amphibians are im- portant prey for numerous arthropod taxa, including ground beetles (Toledo 2005. Herpetol. Rev. 36:395–399; Bernard and Samolg 2014. Entomol. Fennica 25:157–160). Previous studies have shown that Epomis larvae feed exclusively on amphibians and display a unique luring behavior in order to attract their prey FIG. -

A Dialogue on Managing Karnataka's Fisheries

1 A DIALOGUE ON MANAGING KARNATAKA’S FISHERIES Organized by College of Fisheries, Mangalore Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University (www. cofmangalore.org) & Dakshin Foundation, Bangalore (www.dakshin.org) Sponsored by National Fisheries Development Board, Hyderabad Workshop Programme Schedule Day 1 (8th December 2011) Registration Inaugural Ceremony Session 1: Introduction to the workshop and its objectives-Ramachandra Bhatta and Aarthi Sridhar(Dakshin) Management of fisheries – experiences with ‘solutions’- Aarthi Sridhar Group discussions: Identifying the burning issues in Karnataka’s fisheries. Presentation by each group Session 2: Community based monitoring – experiences from across the world- Sajan John (Dakshin) Discussion Day 2 (9th December 2011) Session 3: Overview of the marine ecosystems and state of Fisheries Marine ecosystems - dynamics and linkages- Naveen Namboothri (Dakshin) State of Karnataka Fisheries- Dinesh Babu (CMFRI, Mangalore) Discussion Session 4: Co-management in fisheries Co-management experiences from Kerala and Tamil Nadu- Marianne Manuel (Dakshin) Discussion: What role can communities play in the management of Karnataka’s fisheries? Day 3 (10th December 2011) Field session Field visit to Meenakaliya fishing village to experiment with the idea of 2-way learning processes in fisheries Group Discussion Feedback from the participants and concluding remarks 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Format of the workshop 4 Concerns with fisheries 5 Transitions in fishing technologies and methods -

Expectant Urbanism Time, Space and Rhythm in A

EXPECTANT URBANISM TIME, SPACE AND RHYTHM IN A SMALLER SOUTH INDIAN CITY by Ian M. Cook Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Daniel Monterescu CEU eTD Collection Professor Vlad Naumescu Budapest, Hungary 2015 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no material accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, November, 2015 CEU eTD Collection Abstract Even more intense than India's ongoing urbanisation is the expectancy surrounding it. Freed from exploitative colonial rule and failed 'socialist' development, it is loudly proclaimed that India is having an 'urban awakening' that coincides with its 'unbound' and 'shining' 'arrival to the global stage'. This expectancy is keenly felt in Mangaluru (formerly Mangalore) – a city of around half a million people in coastal south Karnataka – a city framed as small, but with metropolitan ambitions. This dissertation analyses how Mangaluru's culture of expectancy structures and destructures everyday urban life. Starting from a movement and experience based understanding of the urban, and drawing on 18 months ethnographic research amongst housing brokers, moving street vendors and auto rickshaw drivers, the dissertation interrogates the interplay between the city's regularities and irregularities through the analytical lens of rhythm. Expectancy not only engenders violent land grabs, slum clearances and the creation of exclusive residential enclaves, but also myriad individual and collective aspirations in, with, and through the city – future wants for which people engage in often hard routinised labour in the present. -

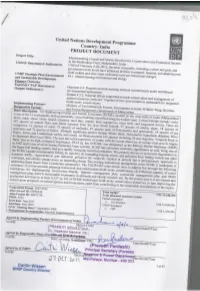

Project Document, and for the Use of Project Funds Through Effective Management and Well Established Project Review and Oversight Mechanisms

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... 3 1. SITUATION ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................... 5 PART 1A: CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Geographic and biodiversity context ..................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Demographic and socio-economic context ............................................................................................ 8 1.3 Legislative, policy, and institutional context ....................................................................................... 11 PART 1B: BASELINE ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................ 17 1.4 Threats to coastal and marine biodiversity of the SCME .................................................................... 17 1.5 Baseline efforts to conserve coastal and marine biodiversity of the SCME ......................................... 21 1.6 Desired long-term solution and barriers to achieving it...................................................................... 22 1.7 Stakeholder analysis ........................................................................................................................... -

Hindu Succession Act, 1956 ______

THE HINDU SUCCESSION ACT, 1956 ____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ____________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title and extent. 2. Application of Act. 3. Definitions and interpretation. 4. Overriding effect of Act. CHAPTER II INTESTATE SUCCESSION General 5. Act not to apply to certain properties. 6. Devolution of interest in coparcenary property. 7. Devolution of interest in the property of a tarwad, tavazhi, kutumba, kavaruorillom. 8. General rules of succession in the case of males. 9. Order of succession among heirs in the Schedule. 10. Distribution of property among heirs in class I of the Schedule. 11. Distribution of property among heirs in class II of the Schedule. 12. Order of succession among agnates and congnates. 13. Computation of degrees. 14. Property of a female Hindu to be her absolute property. 15. General rules of succession in the case of female Hindus. 16. Order of succession and manner of distribution among heirs of a female Hindu. 17. Special provisions respecting persons governed by marumakkattayam and aliyasantana laws. General provisions relating to succession 18. Full blood preferred to half blood. 19. Mode of succession of two or more heirs. 20. Right of child in womb. 21. Presumption in cases of simultaneous deaths. 22. Preferential right to acquire property in certain cases. 23. [Omitted.]. 24. [Omitted.]. 25. Murderer disqualified. 26. Convert’s descendants disqualified. 27. Succession when heir disqualified. 28. Disease, defect, etc., not to disqualify. Escheat 29. Failure of heirs. 1 CHAPTER III TESTAMENTARY SUCCESSION SECTIONS 30. Testamentary succession. CHAPTER IV REPEALS 31. [Repealed.]. THE SCHEDULE. 2 THE HINDU SUCCESSION ACT, 1956 ACT NO. -

A Geographical Analysis of Cashewnut Processing Industry in the Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra”

“A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF CASHEWNUT PROCESSING INDUSTRY IN THE SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA” A Thesis Submitted to TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE For the Degree of Ph.D. Doctor of Philosophy (Vidyawachaspati ) in GEOGRAPHY Under the Faculty of Moral and Social Sciences by PATIL RAJARAM BALASO Lect. & Head Dept. of Geography Arts & Commerce College, Phondaghat Tal : Kankavli Dist : Sindhudurg UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. PRAVEEN G. SAPATARSHI Professor of Sustainability Management Indian Institute of Cost & Management Studies and Research, Pune APRIL 2010 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF CASHEW NUT PROCESSING INDUSTRY IN THE SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA” completed and written by me has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title of this or any other University or examining body. Place: Pune ( Shri. Rajaram B. Patil ) Date: 28-04-2010 Research student ii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF CASHEWNUT PROCESSING INDUSTRY IN THE SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Vidyawachaspati (Ph.D.) in Geography of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of the original research work completed by Shri. Rajaram Balaso Patil under my supervision and guidance. To the best of knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. Place: Pune Dr. Praveen G. Saptarshi Date: 28-04-2010 Research Guide iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While preparing this research work, numerous memories rush through my mind which is full of gratitude to those who encouraged and helped me at various stages. -

Customs and Gender in the Context of Hindu Laws

International Journal of Law and Legal Jurisprudence Studies :ISSN:2348-8212:Volume 4 Issue 2 86 CUSTOMS AND GENDER IN THE CONTEXT OF HINDU LAWS Dr. Paroma Sen1 Abstract There has been an influence of customs in the evolution of Hindu Laws. Hindu laws at times confronted, in other instances incorporated and in few cases overrode customary laws of different regions, however it could not in in any way change the caste based social prejudices. With the context of Haryana in the backdrop this article looks into the influence of customs in the region in the construction of gender identity and to what extent could Hindu Law influence the customs followed. Key words: customary laws, gender, hindu, dayabhaga, mitakshara, inheritance Hindu Law in the Pre-colonial period Origin of Hinduism has given rise to various interpretations. However, there could not be any denying that the consciousness of Hinduism as a religion among its followers arose in countering the identity of Muslims or Islamic presence in different parts of the country with the rise of the Sultanate followed by the Mughal rule. The word Hindu is a Persian term which was used to refer to the inhabitants across river Indus. This reference, points out a strong ethno-geographic2 connotation attached to the rise, development and continuance of Hinduism.The distinctions separating one religion from the followers of the other finally culminated into the partition of the country and eventual division of land based on the religion of its followers. Against this backdrop of the political invasion of the country and conflict among the religious groups, there was also the presence of laws influencing the social spheres of the family and community. -

Detailed Project Report of Sawantwadi Coir Cluster District

Detailed Project Report of Sawantwadi Coir Cluster District: Sindhudurg Maharashtra Submitted to Coir Board Kochi Prepared by NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (An Organization of Ministry of MSME, Government of India) Yousufguda, Hyderabad – 500 045 (INDIA) Detailed Project Report of Sawantwadi Coir Cluster Content Project Summary Chapter 1: Cluster Profile 1.1. Background 1.2. SFURTI 1.3. History of Coir 1.4. Global scenario 1.5. National Scenario 1.6. Maharashtra scenario 1.7. Project Location 1.8. Coconut Cultivation 1.9. Project Overview 1.10. Infrastructure Available Chapter 2: Production Process and Cluster Products 2.1. Cluster Products 2.2. Production process 2.3. Operation process proposed in cluster 2.4. Cluster Map Chapter 3: Market Assessment and Demand Analysis Chapter 4: SWOT and Gap Analysis 4.1 SWOT analysis 4.2 Gap analysis Chapter 5: Profile of Implementing Agency Chapter 6: Project Concept and Strategy Framework 6.1 Project Rationale 6.2 Project Objectives 6.3 Focus Products/ Services 6.4 Project Strategy Chapter 7: Project Interventions Chapter 8: Project cost and Means of Finance Chapter 9: Plan for convergence Initiatives Chapter 10: Project Planning and Monitoring 10.1Project Planning 10.2 Implementation, Monitoring & Evaluation Chapter 1: Financials- Business Plan 11.1 Financials 11.2. Project cost 11.3 Financial structuring 11.4. Assumptions Chapter 12 Implementation Framework Chapter 13 Expected Outcome B List of Acronyms BDS: Business Development Service Providers CDP: Cluster Development -

District Disaster Management Authority Sindhudurg

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN SINDHUDURG UPDATED June 2020 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY SINDHUDURG Disaster Management Programme Govt.Of Maharashtra Executive Summary The District Disaster Management Plan is a key part of an emergency management. It will play a significant role to address the unexpected disasters that occur in the district effectively .The information available in DDMP is valuable in terms of its use during disaster. Based on the history of various disasters that occur in the district ,the plan has been so designed as an action plan rather than a resource book .Utmost attention has been paid to make it handy, precise rather than bulky one. This plan has been prepared which is based on the guidelines provided by the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM)While preparing this plan ,most of the issues ,relevant to crisis management ,have been carefully dealt with. During the time of disaster there will be a delay before outside help arrives. At first, self help is essential and depends on a prepared community which is alert and informed .Efforts have been made to collect and develop this plan to make it more applicable and effective to handle any type of disaster. The DDMP developed involves some significant issues like Incident Command System (ICS), India Disaster Resource Network (IDRN)website, the service of National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) in disaster management .In fact ,the response mechanism ,an important part of the plan is designed with the ICS, a best model of crisis management has been included in the response part for the first time. It has been the most significant tool to the response manager to deal with the crisis within the limited period and to make optimum use of the available resources. -

A Geographical Analysis of Major Tourist Attraction in Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra, India

Geoscience Research ISSN: 0976-9846 & E-ISSN: 0976-9854, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2013, pp.-120-123. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000215 A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF MAJOR TOURIST ATTRACTION IN SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA RATHOD B.L.1, AUTI S.K.2* AND WAGH R.V.2 1Kankawali College Kankawali- 416 602, MS, India. 2Art, Commerce and Science College, Sonai- 414 105, MS, India. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: October 12, 2013; Accepted: December 09, 2013 Abstract- Sindhudurg District has been declared as a 'Tourism District' on 30th April 1997. The natural resources, coastal lines, waterfalls, hot springs, temples, historical forts, caves, wild-life, hill ranges, scenery and amenable climate are very important resources of tourist attrac- tion. The various facilities available to the domestic and foreign tourists in Sindhudurg district. These include natural resources, transportation, infrastructure, hospitality resources and major tourist attractions. For the research work Sindhudurg District is selected. This district has at East Kolhapur district, at south Belgaum and Goa state at North Ratnagiri district and at west Arabian Sea. It is smallest district in Maharashtra state. It's area is 5207 sq.kms. Its geographical Location of Sindhudurg is 150 36' to 160 40' North latitudes as 730 19 to 740 18' East longitude. As per 2001 census it has 743 inhabited villages and 5 towns. The object of study region is, to highlight the attractive tourist destinations and religious places in the region. This study based on primary and secondary data. Tourist attractions in the district as is, natural beauty, waterfall, umala, caves, temples, beaches, ports, forts, mini garden, rock garden, tracking, rock climbing, boating, valley crossing, wild life, festival's fairs, arts, handicrafts, creeks, lakes etc. -

Request for Ceo Endorsement/Approval Project Type: Full Sized Project the Gef Trust Fund

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: FULL SIZED PROJECT THE GEF TRUST FUND Submission Date: May 19, 2011 PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Expected Calendar GEFSEC PROJECT ID: 3941 Milestones Dates Work Program (for FSP) Nov 2009 GEF AGENCY PROJECT ID: 4242 COUNTRY: India CEO Endorsement/ Approval June 2011 PROJECT TITLE: Mainstreaming Coastal and Marine Biodiversity GEF Agency Approval August 2011 Conservation into Production Sectors in the Sindhudurg (Malvan) Implementation Start August 2011 Coast, Maharashtra State, India Mid-term Evaluation March 2014 GEF AGENCY: UNDP OTHER EXECUTING PARTNER: Ministry of Environment & Implementation Completion August 2016 Forests (MoEF), Government of India / Wildlife Wing, Revenue and Forest Department, State Government of Maharashtra GEF FOCAL AREA: Biodiversity GEF-4 STRATEGIC PROGRAM: SO-2, SP-4 Strengthening policy and regulatory frameworks for mainstreaming biodiversity NAME OF PARENT PROGRAM/ UMBRELLA PROJECT: India GEF Coastal and Marine Program (IGCMP) A. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: To mainstream biodiversity conservation considerations into those production sectors that impact coastal and marine ecosystems of the Sindhudurg Coastal and Marine Ecosystem (SCME) Project Type Expected Outcomes Expected Outputs GEF financing Cofinancing Total ($) Components ($) % ($) % 1. Cross-sectoral TA Pressures on the coastal and Landscape-level land use and 386,200 22% 1,400,000 78% 1,786,200 planning marine biodiversity of SCME marine use zoning plan framework that (primarily from commercial and (referred to as the Landscape mainstreams subsistence fisheries and other Plan or LP) that identifies biodiversity production sectors) are areas critical for conservation, conservation significantly reduced and enabling and areas where production considerations environment created for activities can take place and mitigating the impacts of with special requirements for production sectors on the ensuring sustainability.