Onomastica Uralica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

Estimation of Investment Attractiveness of the Mari El Republic

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2017- 4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 10-12 July 2017- Dubai, UAE ESTIMATION OF INVESTMENT ATTRACTIVENESS OF THE MARI EL REPUBLIC Nadezhda V. Kurochkina 1* and Ramziya K. Shakirova 2 1Senior Lecturer, Mari State University, Russia, [email protected] 2Assist. Prof. Dr., Mari State University, Russia, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract This article assesses the investment attractiveness of the Republic of Mari El in comparison with other regions of the Volga Federal District and the Russian Federation. The list of organizations providing active support to investors in the region is presented. The investment attractiveness of the key economic sectors of the region is grounded: agriculture, fuel and energy complex, small and medium business, education, foreign trade and other industries. Keywords: investments, estimation of investment attractiveness, branch of economy, small business, region, Republic of Mariy El. 1. INTRODUCTION Today, the question of assessing the investment attractiveness of individual constituent entities of the Russian Federation is becoming more and more important. Since before investing money an investor needs to evaluate all the advantages and disadvantages of a project so that it turns out to be really cost-effective. Only after a qualitative and comprehensive analysis of all factors, investors can be sure that the investment will be really effective. In this regard, there is a need for a whole system of methods that will enable us to assess the investment climate in the region, identify its strengths and weaknesses, make a forecast for future development and, most importantly, give investors confidence in the outcome. -

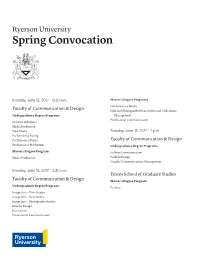

Ryerson University Spring Convocation

Ryerson University Spring Convocation Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Master’s Degree Programs Documentary Media Faculty of Communication & Design Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Undergraduate Degree Programs Management Professional Communication Creative Industries Media Production New Media Tuesday, June 13, 2017 • 1 p.m. Performance Acting Performance Dance Faculty of Communication & Design Performance Production Undergraduate Degree Programs Master’s Degree Program Fashion Communication Media Production Fashion Design Graphic Communications Management Monday, June 12, 2017 • 2:30 p.m. Yeates School of Graduate Studies Faculty of Communication & Design Master’s Degree Program Undergraduate Degree Programs Fashion Image Arts – Film Studies Image Arts – New Media Image Arts – Photography Studies Interior Design Journalism Professional Communication Convocation Program Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Eagle Staff Carrier Mace Carrier and Bedel Tracey King Cynthia Ashperger Aboriginal Human Resources Consultant Director Ryerson Aboriginal Student Services Acting Program School of Performance Convocation Ceremony Invocation Family and friends are requested to rise when the In the toil of thinking; in the serenity of books; in the academic procession enters, and remain standing until messages of prophets, the songs of poets and the wisdom the conclusion of the invocation. of interpreters; in discoveries of continents of truth whose margins we may see; we delight in free minds and in their Following the convocation address, the graduands will thinking. rise for the general presentation of candidates and then resume their seats. Afterwards, graduands will be called In the majesty of the moral order; in the faith that right and presented for the awarding of certificates, and will triumph; in the courage given us when we ally undergraduate and graduate degrees. -

TOTO: the Synth Statesmen of Progressive Pop Return Slideshow

Keyboard Guitar Player Bass Player Electronic Musician Guitar Aficianado Guitar World Mi Pro Music Week Revolver More... AV/PRO AUDIO Audio Media Audio Pro AV Technology Installation Mix Pro Sound News Pro Sound News Europe Residential Systems BROADCAST/RADIO/TV/VIDEO Broadcast & Production Digital Video Government Video Licensing.biz Radio Magazine Radio World CONSUMER ELECTRONICS/GAMING Bike Biz Develop MCV Mobile Entertainment PCR Toy News EDUCATION Edu Wire School CIO Tech & Learning Pubs Guitar Player Search Keyboardmag.com Search Keyboardmag.com Like 755 Follow @keyboardmag Gear Artists Lessons Blogs Video Store Subscribe! Search Keyboardmag.com Gear Artists Lessons Blogs Video Store Subscribe! Gear Keys and Synths Virtual Instruments Live and Studio Accessories News Contests! Native Instruments introduces Symphony Series Brass Console maker Harrison has a $79 DAW that goes up against the big boys MoMinstruments Elastic Drums app reviewed Artists Features Reviews News Martin Gore goes crazy for classic and modular synths on his new solo album TOTO: The Synth Statesmen of Progressive Pop Return Cameron Carpenter plays “Singing in the Rain” Lessons Play Like … Theory Technique How To Keyboard 101 Style Learn Gregg Allman’s classic rock organ style in 5 easy steps Get bigger, better synth pads with these 5 simple techniques 5 ways to play like Jimmy McGriff Blogs Video Store SUBSCRIBE! All Access Subscription Tablet Subscriptions Renew Customer Service Give a Gift Newsletter Subscription TOTO: The Synth Statesmen of Progressive Pop Return BY JERRY KOVARSKY July 13, 2015 Their stats are staggering. The members of Toto have collectively performed on over 500 albums over the course of 38 years, amassing over half a billion unit sales and 200 Grammy nominations. -

Toto – Toto XIV

Toto – Toto XIV (56:43, CD,Frontiers Music/Soulfood, 2015) Seit 1977 sind Toto nun am Start. Heuer kommt Ihr 14. Studioalbum auf den Markt. Schlicht und einfach mit der durchlaufenden römischen Ziffer betitelt: XIV. Acht Jahre sind seit „Falling In Between“ vergangen, dem letzten Studioalbum. Die lange Schaffenspause war der Kreativität nicht abträglich. Der Einstieg in diesen neuesten Output startet mit einem echten Hammer. Nach vorne gerichtete Beats in ‚Running Out Of Time‘ rocken richtig ab. Das ist ein wahrer Headbanger. Das macht Lust auf mehr. Allerdings war es das dann auch schon fast mit Stadionrock. Denn ab jetzt herrscht wieder gut gemachte Langeweile. Allerdings auf eine Art und Weise, die unnachahmlich ist. Toto haben sich die Kunst erarbeitet, Rocksongs in eine seichte Popdecke zu packen. Ab und an hauen Gitarrenriffs vonSteve Lukather dazwischen und Keith Carlock stampft die Trommeln. Das ist wohl das Geheimnis. Musikalisch wird das Album ziemlich aufgebauscht, Horn- Arrangements inklusive, um mit sanften Stimmen den Hörer einzulullen. Joseph Williams ist der Hauptsänger, der von drei Bandmitgliedern und fünf Backroundsänger/innen unterstützt wird. Gleich vier Bassspieler sind aufgeführt. David Hungate steht an erster Stelle. Er gehörte zu den Gründungsmitgliedern von Toto, verliess 1982 die Band und ist nun wieder dabei. Lee Sklar, das ist der Mann mit dem urigen Bartwuchs bis tief zum Bauchnabel, Tim Lefebvre und Tal Wilkenfeld, unter anderem Bassistin bei Jeff Beck, helfen dabei, einen fundierten Klangteppich zu entwickeln. XIV eignet sich hervorragend als Hintergrundmusik in phantastischer Aufnahmequalität, wie nicht anders zu erwarten. Wer noch keine Toto-Scheibe sein eigen nennt, sei zum Kauf dieser Veröffentlichung aufgefordert. -

TOTO Bio (PDF)

TOTO Bio Few ensembles in the history of recorded music have individually or collectively had a larger imprint on pop culture than the members of TOTO. As individuals, the band members’ imprint can be heard on an astonishing 5000 albums that together amass a sales history of a HALF A BILLION albums. Amongst these recordings, NARAS applauded the performances with 225 Grammy nominations. Band members were South Park characters, while Family Guy did an entire episode on the band's hit "Africa." As a band, TOTO sold 35 million albums, and today continue to be a worldwide arena draw staging standing room only events across the globe. They are pop culture, and are one of the few 70s bands that have endured the changing trends and styles, and 35 years in to a career enjoy a multi-generational fan base. It is not an exaggeration to estimate that 95% of the world's population has heard a performance by a member of TOTO. The list of those they individually collaborated with reads like a who's who of Rock & Roll Hall of Famers, alongside the biggest names in music. The band took a page from their heroes The Beatles playbook and created a collective that features multiple singers, songwriters, producers, and multi-instrumentalists. Guitarist Steve Lukather aka Luke has performed on 2000 albums, with artists across the musical spectrum that include Michael Jackson, Roger Waters, Miles Davis, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck, Don Henley, Alice Cooper, Cheap Trick and many more. His solo career encompasses a catalog of ten albums and multiple DVDs that collectively encompass sales exceeding 500,000 copies. -

FIFA World Cup 2022 Booking List Before European Qualifiers Matchday 5

FIFA World Cup 2022 Booking List before European Qualifiers Matchday 5 GROUP A PC European Qualifiers No Player 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Portugal 4 Dos Santos Gato Alves Días Rúben Y * 6 Da Rocha Fonte José Miguel Y No Match * No Match 7 Dos Santos Aveiro Cristiano Ronaldo Y Y 8 Borges Fernandes Bruno Miguel Y Y 16 Luz Sanches Renato Junior Y * 17 Teixeira Da Silva Diogo José Y * Serbia 2 Pavlovic Strahinja Y * 6 Maksimovic Nemanja Y No Match * No Match 9 Mitrovic Aleksandar Y * 4 Milenkovic Nikola R 5 Spajic Uros Y * 8 Gudelj Nemanja Y * Republic of Ireland 3 Stevens Enda Y * 7 Doherty Matthew No Match Y * No Match 13 Hendrick Jeffrey Y * 17 Cullen Joshua Jon Y * 20 O'Shea Dara Y * 21 Conolly Aaron Anthony Y * Luxembourg 2 Chanot Maxime R 4 Bohnert Florian No Match Y * No Match 8 Martins Pereira Christopher Y * 9 Sinani Danel Y * 15 Thill Olivier Y * 18 Jans Laurent Y * Azerbaijan No Match 10 Emreli Mahir Y No Match * 13 Huseynov Abbas Y * 18 Krivotsyuk Anton Y * 19 Khalilzade Tamkin Y * 20 Ozobic Filip Y * S Team staff All Cards from other competitions since last PC initialisation Y Booked R Dismissed Y+R Ordinary Yellow Card and Direct Red Card YP Booked during penalty kicks * Misses next match if booked ** Subject to appeal ### Suspended for at least one match Suspended OOC Out of Competition This list is destined for the press. It is given to the competing teams for information purposes only and therefore has no legal value. -

Symbolic Music Comparison with Tree Data Structures

Ph.D. Thesis Symbolic music comparison with tree data structures Author: Supervisor: David Rizo Valero Jos´eM. Inesta~ Quereda August 2010 The design of the cover by Henderson Bromsted is used under the permission of its owner, the Winston-Salem Symphony. Para Gloria, Pablo y Quique Agradecimientos La elaboraci´onde una tesis es un trabajo ilusionante y arduo, con momentos agradables y dif´ıciles,pero que sobre todo es extenso en el tiempo. Una tarea de estas dimensiones no puede llevarse a cabo por una sola persona aislada. Sin la gu´ıa, apoyo cient´ıfico, t´ecnico,econ´omicoy moral de todas las personas e instituciones que a continuaci´on detallo, esta tesis no habr´ıasalido adelante. Quiero dar gracias especialmente al director de esta tesis, Jos´eManuel I~nesta. El´ ha hecho posible que se estableciera y consolidara nuestro grupo de investigaci´onen inform´aticamusical, haciendo realidad mi sue~nopersonal de investigar en este campo, ha participado activamente en todos y cada uno de los trabajos de investigaci´onen los que he trabajado, ha facilitado la posibilidad de realizar las estancias de investigaci´on en el extranjero, y sobre todo, me ha hecho creer que esta tesis ten´ıasentido. La interacci´oncon los miembros del Grupo de Investigaci´ony Reconocimiento de Formas e Inteligencia Artificial del Departamento de Lenguajes y Sistemas Inform´aticos de la Universidad de Alicante ha enriquecido el contenido de esta investigaci´on. Jos´e Oncina, Mar´ıaLuisa Mic´o,Jorge Calera, Juan Ram´onRico, Rafael Carrasco y Paco Moreno han resuelto muchas de las dudas que se me han ido surgiendo durante este largo proceso. -

The Roots Report: Toto at Twin River

The Roots Report: Toto at Twin River Okee dokee folks… I went to Twin River in Lincoln the other night to check out the band Toto. There was a nearly full house in attendance and from the looks of the array of Toto t-shirts I saw folks wearing, a lot of big fans. I cannot be counted as a big fan. I am a casual listener, but I do enjoy a few of their songs. The lights went down right at 8pm and the backing band members took the stage and rocked a bit before the actual members of Toto — Steve Lukathar, David Paich, Steve Porcaro and Joseph Williams — arrived on stage. They launched into the song, “Only The Children.” Surprisingly, the second song was their debut hit “Hold The Line.” That brought the audience to their feet and they sang along encouraged by lead singer, Joseph Williams. They played three more songs, “Afraid of Love,” “Lovers in the Night” and “Pamela” before I recognized the “lite rock” favorite “I’ll Be Over You.” Williams encouraged fans to light up their phones and wave them in the air. The next song, “Chinatown,” was introduced as originally being written for the Toto I album, but over the years it was re-written and rearranged for the Toto XIV album. They talked about a recently discovered video that they came across of the band performing in Montreux and it inspired them to perform their version of Jimi Hendrix’s “Red House.” This featured a fiery guitar solo by Steve Lukathar. They introduced the band at this point, Lenny Castro (percussion), Warren Ham (saxophone), Shannon Forres (drums) and Shem von Schroeck (bass). -

Chart-Chronology Singles and Albums

www.chart-history.net vdw56 PDF-files with all chart-entries plus covers on https://chart-history.net/chart-chronologie/ TOTO Chart-Chronology Singles and Albums Germany United Kingdom From the 1950ies U S A to the current charts compiled by Volker Dörken Chart - Chronology The Top-100 Singles and Albums from Germany, the United Kingdom and the USA Toto Toto is an American rock band formed in 1976 in Los Angeles. Toto is known for a musical style that combines elements of pop, rock, soul, funk, progressive rock, hard rock, R&B, blues, and jazz. Singles 17 10 4 1 1 Longplay 27 20 8 --- B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 14 6 3 --- --- 4 27 20 7 --- 3 7 4 1 --- 4 7 2 1 --- 1 1 14 10 4 1 4 9 4 2 --- Singles D G B U S A 1 Hold The Line 03/1979 23 02/1979 14 10/1978 5 2 I'll Supply The Love 02/1979 45 3 Georgy Porgy 04/1979 48 4 99 12/1979 26 5 Rosanna 07/1982 24 04/1983 12 04/1982 2 6 Make Believe 03/1983 70 08/1982 30 7 Africa 09/1982 14 01/1983 3 10/1982 1 1 8 I Won't Hold You Back 06/1983 37 03/1983 10 9 Waiting For Your Love 07/1983 73 10 Stranger In Town 01/1985 100 10/1984 30 11 Holyanna 02/1985 71 12 I'll Be Over You 08/1986 11 13 Without Your Love 12/1986 38 14 Pamela 02/1988 22 15 Stop Loving You 03/1988 96 16 I Will Remember 10/1995 82 11/1995 64 17 Goin' Home 06/1998 99 Longplay D G B U S A 1 Toto 02/1979 8 03/1979 37 11/1978 9 2 Hydra 01/1980 38 11/1979 37 3 Turn Back 02/1981 39 02/1981 41 4 Toto IV 05/1982 12 02/1983 4 05/1982 4 5 Isolation 11/1984 15 11/1984 67 11/1984 42 6 Fahrenheit 09/1986 24 09/1986 -

North American History in Europe

North American History in Europe: A Directory of Academic Programs and Research Institutes Reference Guide 2 3 North 23 American Histor y in Europe Eckhardt Fuchs Janine S. Micunek Fuchs D e s i g n : U t GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE e S i e WASHINGTON D.C. w e r t German Historical Institute Reference Guides Series Editor: Christof Mauch German Historical Institute Deutsches Historisches Institut 1607 New Hampshire Ave. NW Washington, DC 20009 Phone: (202) 387-3377 Fax: (202) 483-3430 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.ghi-dc.org Library and Reading Room Hours: Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and by appointment Inquiries should be directed to the librarians [email protected] © German Historical Institute 2007 All rights reserved GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 23 NORTH AMERICAN HISTORY IN EUROPE: ADIRECTORY OF ACADEMIC PROGRAMS AND RESEARCH INSTITUTES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 INSTITUTIONS BY COUNTRY 5 AUSTRIA 5 University of Innsbruck Institute of Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte) ....................................................................... 5 University of Salzburg Departments of History and Political Science (Fachbereich Geschichts- und Politikwissenschaft) ......................................................... 6 University of Vienna Department of History (Institut für Geschichte): Working Group “History of the Americas” (AGGA) ....................... 7 BELGIUM 8 Royal Library of Belgium Center for American Studies (CAS) ..................................................... -

ULYANOVSK OBLAST: Tatiana Ivshina

STEERING COMMITTEE FOR CULTURE, HERITAGE AND LANDSCAPE (CDCPP) CDCPP (2013) 24 Strasbourg, 22 May 2013 2nd meeting Strasbourg, 27-29 May 2013 PRESENTATION OF THE CULTURAL POLICY REVIEW OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION DOCUMENT FOR INFORMATION AND DECISION Item 3.2 of the draft agenda Draft decision The Committee: – welcomed the conclusion of the Cultural Policy Review of the Russian Federation and congratulated the Russian Authorities and the joint team of Russian and independent experts on the achievement; – expressed its interest in learning about the follow-up given to the report at national level and invited the Russian Authorities to report back in this respect at the CDCPP’s 2015 Plenary Session. Directorate of Democratic Governance, DG II 2 3 MINISTRY OF CULTURE RUSSIAN INSTITUTE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH CULTURAL POLICY IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REVIEW 2013 4 The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the editors of the report and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. 5 EXPERT PANEL: MINISTRY OF CULTURE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: Kirill Razlogov Nina Kochelyaeva Tatiana Fedorova MINISTRY OF CULTURE, PRINT, AND NATIONAL AFFAIRS OF THE MARI EL REPUBLIC: Galina Skalina MINISTRY OF CULTURE OF OMSK OBLAST: Tatiana Smirnova GOVERNMENT OF ULYANOVSK OBLAST: Tatiana Ivshina COUNCIL OF EUROPE: Terry Sandell Philippe Kern COUNCIL OF EUROPE COORDINATOR Kathrin Merkle EDITORS AND CONTRIBUTORS Editors: Kirill Razlogov (Russian Federation) Terry Sandell (United Kingdom) Contributors: Tatiana Fedorova (Russian Federation) Tatiana Ivshina (Russian Federation) Philippe Kern (Belgium) Nina Kochelyaeva (Russian Federation) Kirill Razlogov (Russian Federation) Terry Sandell (United Kingdom) Tatiana Smirnova (Russian Federation) 6 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 10 CULTURE POTENTIAL INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER 1.