By Jessi Streib a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

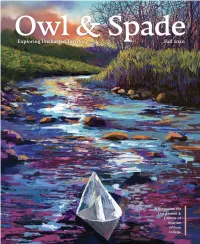

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

2018 GSOC Highest Awards Girl Scout Yearbook

Melanoma Recognizing Orange County 2018 Highest Awards Girl Scouts: Bronze Award Girl Scouts, Silver Award Girl Scouts, and Gold Award Girl Scouts Earned between October 2017 - September 2018 1 The Girl Scout Gold Award The Girl Scout Gold Award is the highest and most prestigious award in the world for girls. Open to Girl Scouts in high school, this pinnacle of achievement recognizes girls who demonstrate extraordinary leadership by tackling an issue they are passionate about – Gold Award Girl Scouts are community problem solvers who team up with others to create meaningful change through sustainable and measurable “Take Action” projects they design to make the world a better place. Since 1916, Girl Scouts have been making meaningful, sustainable changes in their communities and around the world by earning the Highest Award in Girl Scouting. Originally called the Golden Eagle of Merit and later, the Golden Eaglet, Curved Bar, First Class, and now the Girl Scout Gold Award, this esteemed accolade is a symbol of excellence, leadership, and ingenuity, and a testament to what a girl can achieve. Girl Scouts who earn the Gold Award distinguish themselves in the college admissions process, earn scholarships from a growing number of colleges and universities across the country, and immediately rise one rank in any branch of the U.S. military. Many have practiced the leaderships skills they need to “go gold” by earning the Girl Scout Silver Award, the highest award for Girl Scout Cadettes in grade 6-8, and the Girl Scout Bronze Award, the highest award for Girl Scout Juniors in grades 4-5. -

“The Social Cut of Black and Yellow Female Hip Hop” Erick Raven

“The Social Cut of Black and Yellow Female Hip Hop” Erick Raven University of Texas at Arlington May 2020 Abstract Korean female hip hop artists are expanding the definition of femininity in South Korea through hip hop. In doing so, they are following a tradition first established by Black female musical performers in a new context. Korean artists are conceiving and expressing, through rap and dance, alternative versions of a “Korean woman,” thus challenging and attempting to add to the dominant conceptions of “woman.” This Thesis seeks to point out the ways female Korean hip hop artists are engaging dominant discourse regarding skin tone, body type, and expression of female sexuality, and creating spaces for the development of new discourses about gender in South Korean society. Contents Introduction – Into the Cut ................................................ 1 Chapter I – Yoon Mi-rae and Negotiating the West and East of Colorism ............................................................. 12 Chapter II – The Performing Black and Yellow Female Body ................................................................................ 31 Chapter III – Performing Sexuality ................................. 47 Chapter IV – Dis-Orientation .......................................... 59 Conclusion .................................................................... 67 Works Cited .................................................................... 70 Introduction – Into the Cut Identities are performed discourse; they are formed when those who identify as a particular personality perform and establish a discourse in a particular social context. As George Lipsitz states, “improvisation is a site of encounter” (61). In South Korea, female Korean hip hop is the site of a social cut in dominant culture and has become a space of improvisation where new, counter-hegemonic identities are constructed and performed. In this Thesis, I argue that Korean female hip hop artists are enacting a social rupture by performing improvised identities. -

Hip-Hop and Cultural Interactions: South Korean and Western Interpretations

HIP-HOP AND CULTURAL INTERACTIONS: SOUTH KOREAN AND WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS. by Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Sociology May 2017 Committee Members: Nathan Pino, Chair Rachel Romero Rafael Travis COPYRIGHT by Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina 2017 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. DEDICATION To Frankie and Holly for making me feel close to normal. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to acknowledge my mom, dad, and sister first and foremost. Without their love and support over the years, I would not have made it this far. They are forever my cheerleaders, no matter how sassy I may be. Professor Nathan Pino was my chosen mentor who took me under his wing when I chose him like a stray cat. His humor and dedication to supporting me helped me keep my head up even when I felt like I was drowning. Professor Rachel Romero was the one to inspire me to not only study sociology, but also to explore popular culture as a key component of society. -

I S S U E 4 - M a S S M E D I a Finxerunt Issue 5 - Mass Media

I S S U E 4 - M A S S M E D I A FINXERUNT ISSUE 5 - MASS MEDIA S T A F F J O U R N A L I S T S M A G A Z I N E E D I T O R S - i - Imagine, Create, Elevate is a bi-monthly student publication at Finxerunt Policy Institute of which analytically deepens the focus on a vast array socioeconomic issues are the world. Through journalism, the mission of Imagine, Create, Elevate is to elevate student voices as a part of Finxerunt's Student Civic Engagement campaign. In Latin, Finxerunt means to imagine and create. And it’s been a word that has inspired hundreds of students to take initiative around the world since 2017. As a growing non-profit organization, our mission is to go beyond passive activism by empowering the youth to address socio- economic issues and lead tangible change to build a sustainable future with the philosophy that anyone can make a positive difference regardless of race or gender. F I N X E R U N T N O N - P R O F I T L L C T A X I D : 8 5 - 3 5 2 7 1 0 2 I N F O @ F I N X E R U N T . O R G - i i - Table of Contents Article Name Page Number Investigative Articles: The Ascendancy of the News. ....................................................................................................... 01 Did Social Media Determine Our Electoral Results?.....................................................................04 Social Media has Greatly Influenced our Social Skills.................................................................07 Pandemic Perfection?................................................................................................................... -

Congratulations to the Cedars-Sinai Caregivers Mary C

Congratulations to the Cedars-Sinai caregivers Mary C. Adams, RN 1 listed below on being honored through the Circle of Friends program. We thank them for their Mecca Adams, RN 1 outstanding care and concern for our patients and Melinda A. Adams, RN, BSN, RNC 3 their families. Natasha Adamski 2 Stephanie Abad, RN 1 Kenneth W. Adashek, MD, FACS 48 Shirley B. Abatay, RN 3 Christina L. Adberg, MD 3 Sadeea Q. Abbasi, MD 1 Gabrielle L. Adem, RN, BSN 2 Shadi Abdelnour, MD 1 Myriam N. Affognon, RN 1 Coleen J. Abelarde, RN, BC, BSN 2 Elham Afghani, MD, MPH 2 Roland Abella, RN 1 Afshin Afrashteh, MD 2 Nara Abouchian, LVN 1 Hamed Afshari, RN 1 Azieb T. Abraham, CP 1 David E. Aftergood, MD 13 Harmik Abrahamian, RN 1 Massoud H. Agahi, MD 5 Cheryl L. Abrazado, RN 3 Keith L. Agre, MD 20 Tatiana T. Abrekov, RN, BSN 1 Kevin M. Aguila, RN 1 Krystianne N. Abrenica, RN 6 Edward P. Aguilar 1 Rachel Abuav, MD 18 Eloisa R. Aguilar, CP 2 Irene A. Abutin, CP 1 Ericson A. Aguilar, Sr. 1 Emelia Achampong, CP 2 Janice M. Aguilar, RN 1 Anne L. Ackerman, MD, PhD 3 Mil Mirasol L. Aguilar 1 Marie K. Acorda Reece, RN, MSN, 9 ANP-BC, CCTC Nelson D. Aguilar 1 Felicitas M. Acosta 6 Paul Y. Aguilar 1 Frank L. Acosta, Jr., MD 2 Tatiana Aguilar 1 Monique R. Acosta, RN 2 Margarito G. Aguirre 1 Prince Acquah, RN 1 David B. Agus, MD 1 Bessie Adams 3 Daniel D. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study One of The

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study One of the most popular and widely used social media for young people today is Instagram (Smart Insight, 2016, as cited in (Fardouly, et al, 2017). More than 1 billion active monthly users in the world (Instagram Statistics, 2019). As is generally known Instagram social media is a photo and video-based social network that shares an average of 95 million photos and videos per day (Pew Research Center, 2018; Fardouly et al, 2017). Because the existence of Instagram is increasingly popular, Instagram adds several new features that are characteristic of the application, these features are IGTV and Instagram Stories. Instagram features are features that are suitable for content creators and marketers on Instagram. As mentioned before, Instagram users are diverse from every class of young people including celebrities. In addition to communicating and posting their activities with their fans, these celebrities also use Instagram as a platform to promote something of their own, can be in the form of goods, or even their works. Thus, Instagram is an important social media platform because many celebrities prefer to use Instagram to communicate with their fans compared to other social media platforms. 2 Many celebrities from all over the world use Instagram, as well as South Korean celebrities who also choose to use Instagram. In addition to communicating with their fans, South Korean celebrities also use Instagram as a place to spread Korean pop culture throughout the world or can be called as the "Korean Wave". It was stated that the spread of the Korean Wave had begun around the 1990s outside South Korea, and began to become increasingly known around the 2000s. -

UTD Syllabus PSY4344 Fall15

Course CLDP 4344 – 001 CHILD PSYCHOPATHOLOGY PSY 4344 –-- 001 CHILD PSYCHOPATHOLOGY Professor Dr. Jessi Harkins Term Fall 2015 Meetings GR 4.301 on Tu/Th 1:00 – 2:15 pm Professor’s Contact Information Office Phone TBD Office Location JO 4.314 Email Address [email protected] Office Hours 11:30-12:30 Tues/Thurs by appointment; Additional office hours by appointment, only Teaching Assistant Brittany Boyer [email protected] GR 4.604 Office Hours: 10-11am Mon/Wed Additional office hours by appointment, only General Course Information Pre-requisites, CLDP/PSY 2314 or CLDP/PSY 3310 or Co-requisites, CLDP/PSY 3339 or equivalent & other restrictions Course This course introduces and identifies mental disorders and maladaptive Description behaviors in infants, children and adolescents. Students will be introduced to theories of child psychopathology, to diseases of the mind, and to the etiology, treatment, and prevention of these diseases. The impact of genetics and the environment will be discussed and how the maladaptive behaviors can influence family and social relationships. PSY 4344 FALL 2015 Page 1 Learning After completing the course, students should have a better understanding Outcomes and comprehension of the multiple factors that affect and determine psychopathology and maladaptive behaviors in infants, children, and adolescents. The students will: • Learn about theoretical issues that explain the origins of child psychopathology and maladaptive behaviors. • Understand the biological influences and the impact of the environment on childhood mental disorders. This information includes how these factors affect the origins of mental pathology, and how the disorders can be treated and prevented. • Know the most frequently occurring mental disorders and how these disorders influence a child’s development and family and social relationships. -

Flowsik Dating Anyone Right Now and Who at Renuzap.Podarokideal.Ruality: American

Flowsik was born in the borough of Queens, New York City on April 5, He was interested in music from a young age, and played both the trumpet and baritone horn while growing up. He graduated from Queens College with a degree in English literature in Career to. May 15, · Flowsik is a 35 years old Rapper, who was born in April, in the Year of the Ox and is a Aries. His life path number is 5. Flowsik’s birthstone is Diamond and birth flower is Sweet Pea/Daisy. Find out is Flowsik dating anyone right now and who at renuzap.podarokideal.ruality: American. Flowsik dating - Want to meet eligible single man who share your zest for life? Indeed, for those who've tried and failed to find the right man offline, rapport can provide. Find single man in the US with mutual relations. Looking for romance in all the wrong places? Now, try the right place. Register and search over 40 million singles: voice recordings. Flowsik Profile And Facts Flowsik (플로우식) is a Korean-American rapper and singer under South Paw Records. He debuted in as a member of the hip-hop trio Aziatix. He released his first solo single, ‘The Calling’ in Stage Name: Flowsik (플로우식) Birth Name: Jay Pak Korean Name: Pak Dae-sik (박대식) Birthday: April 5, Zodiac Sign: Aries Nationality: [ ]. Mar 30, · Rapper Flowsik denied he and Jessi had sparks outside of the studio. The two rappers collaborated for Flowsik's new single "All I Needs", and in the . Oct 19, · Flowsik, who was born and raised in Queens, New York, began his music career as an underground rapper. -

Fatal Remedies: Child Sexual Abuse and Education Policy in Liberia by Jessi Hanson-Defusco Bachelor of Arts, Colorado State

Title Page Fatal Remedies: Child Sexual Abuse and Education Policy in Liberia by Jessi Hanson-DeFusco Bachelor of Arts, Colorado State University, 2003 Master of Education, Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS This dissertation was presented by Jessi Hanson-DeFusco It was defended on March 3, 2020 and approved by Louis A. Picard, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Paul J. Nelson, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Maureen McClure, Professor, School of Education and Institute for International Studies in Education Gilberto Mendez, PhD and Education Consultant, University of New Mexico Thesis Advisor/Dissertation Director: William Dunn, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs ii Copyright © by Jessi Hanson-DeFusco 2020 iii Abstract Fatal Remedies: Child Sexual Abuse and Education Policy in Liberia Jessica Hanson-DeFusco, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 One of the unintended consequences of international education policy is the misunderstanding of the relationship between child sexual abuse and girls’ schooling. Development research indicates that education is associated with decreased rates of early childhood marriage. Yet education also exposes female pupils to sexual violence within schools. Nevertheless, international agencies and national governments are often unaware that the very policy of putting young girls in the classroom may also expose them to various forms of child sexual abuse. The relationship between schooling and sexual violence has not been well- established in development research. -

Circle of Friends Zahra Aghaalian Dastjerdi 1 Program

Elham Afghani, MD 2 Afshin Afrashteh, MD 3 Hamed Afshari, RN 1 David E. Aftergood, MD 25 Congratulations to the Cedars-Sinai caregivers listed Massoud H. Agahi, MD 5 below on being honored through the Circle of Friends Zahra Aghaalian Dastjerdi 1 program. We thank them for their outstanding care and Keith L. Agre, MD 24 concern for our patients and their families. Kevin M. Aguila, RN 1 Edward P. Aguilar 1 Stephanie Abad, RN 1 Eloisa R. Aguilar, CP 2 Oscar F. Abarca 1 Ericson A. Aguilar, Sr. 1 Shirley B. Abatay, RN 3 Janice M. Aguilar, RN 1 Sadeea Q. Abbasi, MD 1 Mil Mirasol L. Aguilar 1 Shadi Abdelnour, MD 3 Nelson D. Aguilar 1 Ryan Abdul-Haqq, MD 5 Patricia Y. Aguilar 1 Coleen J. Abelarde, RN, BC, BSN 2 Paul Y. Aguilar 1 Roland Abella, RN 1 Tatiana Aguilar 1 Ramona L. Abney, CN III 1 Lourdes Aguirre 2 Nara Abouchian, LVN 1 Margarito G. Aguirre 1 Azieb T. Abraham, CP 1 David B. Agus, MD 1 Harmik Abrahamian, RN 1 Lilibeth A. Agustin, CN IV 1 Cheryl L. Abrazado, RN 3 Daniel D. Agyemang 1 Tatiana T. Abrekov, RN, BSN 1 Julianne Ahdout 1 Krystianne N. Abrenica, RN 6 Sonu S. Ahluwalia, MD 14 Rachel Abuav, MD 25 Maryam Ahmadian, RN, NP 6 Irene A. Abutin, CP 1 Jamil Ahmed, CP 3 Emelia Achampong, CP 2 Shahzad Ahmed, MD 1 A. Lenore Ackerman 5 Betty S. Ahn, MD 1 Mary Alice J. Ackerman, NP 1 Esther S. Ahn, MD 1 Marie K. Acorda Reece, RN, MSN, ANP-BC, CCTC 9 Thomas G. -

The Impact of African-American Musicianship on South Korean Popular Music: Adoption, Appropriation, Hybridization, Integration, Or Other?

The Impact of African-American Musicianship on South Korean Popular Music: Adoption, Appropriation, Hybridization, Integration, or Other? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Gardner, Hyniea. 2019. The Impact of African-American Musicianship on South Korean Popular Music: Adoption, Appropriation, Hybridization, Integration, or Other?. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004187 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Impact of African-American Musicianship on South Korean Popular Music: Adoption, Appropriation, Hybridization, Integration, or Other? Hyniea (Niea) Gardner A Thesis in the Field of Anthropology and Archaeology for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2019 © May 2019 Hyniea (Niea) Gardner Abstract In 2016 the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) reported that the Korean music industry saw an overseas revenue of ₩5.3 trillion ($4.7 billion) in concert tickets, streaming music, compact discs (CDs), and related services and merchandise such as fan meetings and purchases of music artist apparel and accessories (Kim 2017 and Erudite Risk Business Intelligence 2017). Korean popular music (K-Pop) is a billion-dollar industry. Known for its energetic beats, synchronized choreography, and a sound that can be an amalgamation of electronica, blues, hip-hop, rock, and R&B all mixed together to create something that fans argue is “uniquely K-Pop.” However, further examination reveals that producers and songwriters – both Korean and the American and European specialists contracted by agencies – tend to base the foundation of the K-Pop sound in hip-hop and R&B, which has strong ties to African-American musical traditions.