ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Garson Kanin's Born Yesterday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre

917-854-2086 American and Canadian citizen Member of SSDC www.joelfroomkin.com [email protected] Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre Artistic Director The New Huntington Theatre, Huntington Indiana. The Supper Club (upscale cabaret venue housing musical revues) Director/Creator Productions include: Welcome to the Sixties, Hooray For Hollywood, That’s Amore, Sounds of the Seventies, Hoosier Sons, Puttin’ On the Ritz, Jekyll and Hyde, Treasure Island, Good Golly Miss Dolly, A Christmas Carol, Singing’ The King, Fly Me to the Moon, One Hit Wonders, I’m a Believer, Totally Awesome Eighties, Blowing in the Wind and six annual Holiday revues. Director (Page on Stage one-man ‘radio drama’ series): Sleepy Hollow, Treasure Island, A Christmas Carol, Jekyll and Hyde, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, Different Stages (320 seat MainStage) The Sound of Music (Director/Scenic & Projection Design) Moonlight and Magnolias (Director/Scenic Design) Les Misérables (Director/Co-Scenic and Projection Design) Productions Lord of the Flies (Director) Manchester University The Laramie Project (Director) Manchester University The Foreigner (Director) Manchester University Infliction of Cruelty (Director/Dramaturg) Fringe NYC, 2006 *Winner of Fringe 2006 Outstanding Excellence in Direction Award Thumbs, by Rupert Holmes (Director) Cape Playhouse, MA *Cast including Kathie Lee Gifford, Diana Canova (Broadway’s Company, They’re Playing our Song), Sean McCourt (Bat Boy), and Brad Bellamy The Fastest Woman Alive (Director) Theatre Row, NY *NY premiere of recently published play by Outer Critics Circle nominee, Karen Sunde *published Broadway Musicals of 1928 (Director) Town Hall, NYC *Cast including Tony-winner Bob Martin, Nancy Anderson, Max Von Essen, Lari White. -

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21St- Century Actress

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2009 Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bealer, Marcie Danae, "Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress" (2009). Honors Theses. 24. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/24 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Honors Thesis Ouachita Baptist University Spring 2009 Bealer 2 Finding a place to begin, discussing the role Tennessee Williams has played in the American Theatre is a daunting task. As a playwright Williams has "sustained dramatic power," which allow him to continue to be a large part of American Theatre, from small theatre groups to actor's workshops across the country. Williams holds a central location in the history of American Theatre (Roudane 1). Williams's impact is evidenced in that "there is no actress on earth who will not testify that Williams created the best women characters in the modem theatre" (Benedict, par 1). According to Gore Vidal, "it is widely believed that since Tennessee Williams liked to have sex with men (true), he hated women (untrue); as a result his women characters are thought to be malicious creatures, designed to subvert and destroy godly straightness" (Benedict, par. -

The Glorious Career of Comedienne Judy Holliday Is Celebrated in a Complete Nine-Film Retrospective

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1996 Contact: Graham Leggat 212/708-9752 THE GLORIOUS CAREER OF COMEDIENNE JUDY HOLLIDAY IS CELEBRATED IN A COMPLETE NINE-FILM RETROSPECTIVE Series Premieres New Prints of Born Yesterday and The Marrying Kind Restored by The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday December 27,1996-January 4,1997 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Special Premiere Screening of the Restored Print of Born Yesterday Introduced in Person by Betty Comden on Monday, December 9,1996, at 6:00 p.m. Judy Holliday approached screen acting with extraordinary intelligence and intuition, debuting in the World War II film Winged Victory (1944) and giving outstanding comic performances in eight more films from 1949 to 1960, when her career was cut short by illness. Beginning December 27, 1996, The Museum of Modern Art presents Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday, a complete retrospective of Holliday's short but exhilarating career. Holliday's experience working with director George Cukor on Winged Victory led to a collaboration with Cukor, Garson Kanin, and Kanin's wife Ruth Gordon, resulting in Adam's Rib (1949), Born Yesterday (1950), The Marrying Kind (1952), and // Should Happen To You (1952). She went on to make Phffft (1954), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956), Full of Life (1956), and, for director Vincente Minnelli, Bells Are Ringing (1960). -more- 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Entertainment are restoring the six films that Holliday made at Columbia Pictures from 1950 to 1956. -

12-13 Season Brochure.Indd

2012 2013 SEASON The Department of Theatre Arts has a strong tradition of excellence in graduate training, preparing professional stage directors and theatre scholars through MFA and MA programs. With small classes and strong mentorship by professors, our graduate programs offer graduate education with intensive and Gruesome Playground Injuries personalized training. directed by John Michael Sefel Baylor theatre audiences experience the work of graduate students in the MFA Directing program who direct regularly in our theatre season. Join us this season as we jet off to the French Riviera for a “dirty, The “MIDSUMMER SEASON” rotten” musical, followed by an ancient Greek tragedy. In the At the end of the first year of study, MFA Directing students are spring, we’ll laugh along with an required to design and direct a full-length play for our summertime “Midsummer Season.” Recent summer shows include Eleemosynary, American comedy classic, hang OTMA, and Circle Mirror Transformation. The summer productions on for an outrageously funny for 2012 were Rajiv Joseph’s Gruesome Playground Injuries directed Hitchcock thriller, and end the by John Michael Sefel, a graduate student from New Hampshire, season in the twilight of and Kenny Finkle’s Indoor/Outdoor directed by Nathan Autrey who communist rule on the eve of came to Baylor’s graduate program from the Dallas area. the Romanian Revolution. Thesis Shows The 2012–2013 Baylor Theatre season has it all. To complete the MFA in Directing, third-year graduate students must serve as a director in Stan Denman our mainstage season of shows, leading a Baylor Theatre production team of faculty, staff, and students throughout the production process from Chair research to rehearsal to performance. -

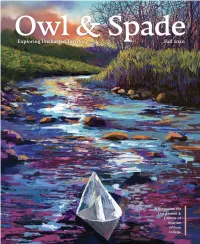

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

From from Reverence to Rape Female Stars of the 1940S

MOLLY HASKELL IIIIIIIIHIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIRIIIIII"Itlltottllllllnlta�rt111111111111J1HIIIIIIIIII1IIIIIl&IMWIIIIIIII1k.ll-611111lll"lltltiiiiii111111111111HHIIIIIIHIIIIIIIIII1niiiiiiiiii1Uit111111111HIIUIHIIIIIIIIIIIIIIJ111UIIIIIIIIUUIII&IIIIII,.IIIIatlllll From From Reverence to Rape Female Stars of the 1940s Molly Haskell's From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women m the MoVIes (197311S a p oneenng examination of the roles p ayed by women n film and what these ro es tell us about the place of women 1n society, changmg gender dynam ics, and shiftmg def1mt1ons of love and fam1ly Haskell argues that women were berng tncreas ngly ob1ecttf1ed and v1hfled tn the films of the 1960s and 1970s. Tttrs femrntst perspective informs a I of Haskell's work, whtch takes a nuanced vtew of the complex relation of men and women to ftlm and power. Holdmg My Own m No Man's Land Women and Men. Ftlm and Femimsts (1997) includes essays and mtervrews on femimst issues surroundmg ftlm and literature. Haskell prov'des analyses and apprec1at1ons of proto-femimst f1lms of the th1rtres, fortres, and frfttes, celebrating actresses hke Mae West and Doris Day for the1r umque forms of empowerment. She continues to write rev1ews for Town and Country and The Vlllage Votce. The preoccupation of most movies of the fo rties, particularly the "masculine" genres, is with man's soul and salvation, rather than with woman's. It is man's prerogative to fo llow the path from blindness to discovery, which is the principal movement of fiction. In the bad-girl films like Gilda and Om cifthe Past, it is the man who is being corrupted, his soul which is in jeopardy. -

Hollywood's Image of the Working Woman

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1995 Hollywood's image of the working woman Jody Elizabeth Dawson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Dawson, Jody Elizabeth, "Hollywood's image of the working woman" (1995). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 516. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/f1nc-wwio This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

032343 Born Yesterday Insert.Indd

among others. He is a Senior Fight Director with OUR SPONSORS ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY Dueling Arts International and a founding member of Dueling Arts San Francisco. He is currently Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the Center REP is the resident, professional theatre CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY teaching combat related classes at Berkeley Rep leading corporate sponsor of Center REP and company of the Lesher Center for the Arts. Our season Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director School of Theatre. the Lesher Center for the Arts for the past nine consists of six productions a year – a variety of musicals, LYNNE SOFFER (Dialect Coach) has coached years. In fact, Chevron has been a partner of dramas and comedies, both classic and contemporary, over 250 theater productions at A.C.T., Berkeley the LCA since the beginning, providing funding that continually strive to reach new levels of artistic presents Rep, Magic Theatre, Marin Theater Company, for capital improvements, event sponsorships excellence and professional standards. Theatreworks, Cal Shakes, San Jose Rep and SF and more. Chevron generously supports every Our mission is to celebrate the power of the human Opera among others including ten for Center REP. Center REP show throughout the season, and imagination by producing emotionally engaging, Her regional credits include the Old Globe, Dallas is the primary sponsor for events including Theater Center, Arizona Theatre Company, the intellectually involving, and visually astonishing Arena Stage, Seattle Rep and the world premier the Chevron Family Theatre Festival in July. live theatre, and through Outreach and Education of The Laramie Project at the Denver Center. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills.