Naturally Disturbed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Chapter Five

Chapter Five The Heroic Years of Mildura Part II: 1975 – 1978 Introduction In Australia, as in much of the western world, including England and the United States, the period between 1975 and 1978 was one of economic and political turbulence. The ongoing stagflation, severe cuts to government spending and high rates of unemployment were common and signalled the end of the post-war boom and the beginning of a period of economic volatility and austerity. As discussed in chapter three, the Whitlam Labor Government was voted in with substantial majorities in both the 1972 and 1974 elections, the latter being a double dissolution election with an even balance of power between Labor and the Liberal-National Country Party in the Senate. Although committed to implementing major social policies and administrative reforms that required significant government investment, Australia’s increasingly precarious economic circumstances throughout 1975 – highlighted by an overseas loans scandal and resulting in the resignation of two cabinet ministers – led to the Senate blocking the supply bill. The deadlock was broken with the Governor-General’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government and the installation of Malcolm Fraser and the Liberal-National Country Party coalition as the caretaker government on Remembrance Day, 11 November 1975. The controversy surrounding the constitutional crisis that emanated from this action had powerful reverberations throughout the Australian art world. Although the coalition won the 1975 238 and 1977 elections with overwhelming -

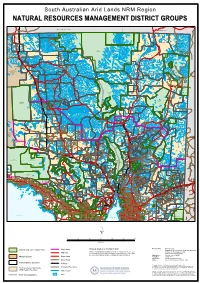

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications

M01 Mineral Exploration Licence Applications 27 September 2021 Resources and Energy Group L4 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide SA 5000 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/minerals GPO Box 320, ADELAIDE, SA 5001 http://energymining.sa.gov.au/energy_resources Phone +61 8 8463 3000 http://map.sarig.sa.gov.au Email [email protected] Earth Resources Information Sheet - M1 Printed on: 27/09/2021 M01: Mineral Exploration Licence Applications Year Lodged: 1996 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1996/00118 NiCul Minerals Limited Mount Harcus area - Approx 400km 2,415 Lindsay, WNW of Marla Woodroffe 1996/00185 NiCul Minerals Limited Willugudinna Hill area - Approx 823 Everard 50km NW of Marla 1996/00260 Goldsearch Ltd Ernabella South area - Approx 519 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00262 Goldsearch Ltd Marble Hill area - Approx 80km NW 463 Abminga, of Marla Alberga 1996/00340 Goldsearch Ltd Birksgate Range area - Approx 2,198 Birksgate 380km W of Marla 1996/00341 Goldsearch Ltd Ayliffe Hill area - Approx 220km NW 1,230 Woodroffe of Marla 1996/00342 Goldsearch Ltd Musgrave Ranges area - Approx 2,136 Alberga 180km NW of Marla 1996/00534 Caytale Pty Ltd Bull Hill area - Approx 240km NW of 1,783 Woodroffe Marla Year Lodged: 1997 File Ref. Applicant Locality Fee Zone Area (km2 ) 250K Map 1997/00040 Minex (Aust) Pty Ltd Bowden Hill area - Approx 300 WNW 1,507 Woodroffe of Marla 1997/00053 Mithril Resources Limited Mt Cooperina Area - approx. 360 km 1,013 Mann WNW of Marla 1997/00055 Mithril Resources Limited Oonmooninna Hill Area - approx. -

Sasa Naturally Disturbed

NATURALLY DISTURBED NATURALLY DISTURBED6 APRIL - 7 MAY 2010 6 APRIL -7 MAY 2010 SASA GALLERYSASA GALLERY NATURALLY DISTURBED Artist Sue Kneebone Curators Sue Kneebone & Dr Philip Jones External Scholar Dr Philip Jones, Senior Curator Anthropology Department, South Australian Museum Editor Mary Knights, Director, SASA Gallery Catalogue design Keith Giles Front image: Sue Kneebone, For better or for worse, 2009, giclèe print Inside cover: Sue Kneebone, Hearing Loss (detail), 2009, native pine telegraph pole, sound, furniture Back cover: Sue Kneebone, A delicate menace, 2008, giclèe print Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia. SLSA : C949 (detail) Part of South Australia Shewing the Recent Discoveries, Surveyor-General’s Office, 1859 2 Contents 5 Introduction Mary Knights 7 A Yardea frontier Philip Jones 14 Inland Memories Sue Kneebone 21 Acknowledgements 3 Sue Kneeebone, Yardea Station, photograph, 2008 4 Introduction Naturally Disturbed is the result of an interdisciplinary The SASA Gallery supports a program of exhibitions collaboration between Sue Kneebone and Philip Jones. focusing on innovation, experimentation and The exhibition engages with the complex history, performance. With the support of the Division of intersecting narratives and unexplained absences that Education, Art and Social Sciences and the Division relate to Yardea, a pastoral property in the Gawler Research Performance Fund, the SASA Gallery is being Ranges in South Australia, once managed by Sue developed as a leading contemporary art space Kneebone’s great grandfather. The exhibition is publishing and exhibiting high-quality research based underpinned by research into family, history and place, work, and as an active site of teaching and learning. The and considers the roles that environmental philosophy SASA Gallery showcases South Australian artists, and fieldwork play in contextualising histories. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia 2001 ______

____________________________________________________ A VEGETATION MAP OF THE WESTERN GAWLER RANGES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 2001 ____________________________________________________ by T. J. Hudspith, A. C. Robinson and P.J. Lang Biodiversity Survey and Monitoring National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia 2001 ____________________________________________________ i Research and the collation of information presented in this report was undertaken by the South Australian Government through its Biological Survey of South Australia Program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the South Australian Government or the Minister for Environment and Heritage. The report may be cited as: Hudspith, T. J., Robinson, A. C. and Lang, P. J. (2001) A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia (National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia, Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia). ISBN 0 7590 1029 3 Copies may be borrowed from the library: The Housing, Environment and Planning Library located at: Level 1, Roma Mitchell Building, 136 North Terrace (GPO Box 1669) ADELAIDE SA 5001 Cover Photograph: A typical Triodia covered hillslope on Thurlga Station, Gawler Ranges, South Australia. Photo: A. C. Robinson. ii _______________________________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia ________________________________________________________________________________ PREFACE ________________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Western Gawler Ranges, South Australia is a further product of the Biological Survey of South Australia The program of systematic biological surveys to cover the whole of South Australia arose out of a realisation that an effort was needed to increase our knowledge of the distribution of the vascular plants and vertebrate fauna of the state and to encourage their conservation. -

![OH (Yardea) Page 1 of 3, A3, 23/06/2016 Mahanewo [Varied by Court Order 06/04/2018] Lake Everard Pastoral Lease Pastoral Lease](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3496/oh-yardea-page-1-of-3-a3-23-06-2016-mahanewo-varied-by-court-order-06-04-2018-lake-everard-pastoral-lease-pastoral-lease-2463496.webp)

OH (Yardea) Page 1 of 3, A3, 23/06/2016 Mahanewo [Varied by Court Order 06/04/2018] Lake Everard Pastoral Lease Pastoral Lease

135°0'E 135°15'E 135°30'E 135°45'E 136°0'E 136°15'E 136°30'E NNTR attachment: SCD2016/001 Schedule 2 - Part B - OH (Yardea) Page 1 of 3, A3, 23/06/2016 Mahanewo [varied by court order 06/04/2018] Lake Everard Pastoral Lease Pastoral Lease OH (Gairdner) OH (Childara) Moonaree Mahanewo South OH (Torrens) Pastoral Lease Lake Gairdner Pastoral Lease Yarna Pastoral Lease 32°0'S 32°0'S Lake Acraman Lake Gairdner Kondoolka National Park Beacon Hill Pastoral Lease Pastoral Lease Hiltaba Pastoral Lease Koweridda Barngarla Determination Area Pastoral Lease Mt Ive SAD6011/1998 Pastoral Lease 32°15'S 32°15'S Schedule 2 - Part B Yardea Pastoral Lease OH (StreakyBay) Siam Pastoral OH (Yardea) Lease Pt Hiltaba Unalla PL Pastoral Lease Mapsheet 1 of 3 Nonning Kolendo Pastoral Lease 0 10 20 30 Pastoral Lease kilometres Thurlga Map Datum : GDA94 Lockes Claypan Pastoral Lease Pastoral Lease 32°30'S Mt Ive 32°30'S Pastoral Lease Native Title Exists Hundred of Augusta)OH (Port Bockelberg Exclusive Native Title Exists Gawler See See Gawler Ranges Ranges OH (Yardea) OH (Yardea) National Park Native Title Extinguished Mapsheet 2 Mapsheet 3 Hundred of Hundred of Kaldoonera Kaldoonera Conservation Park Native Title Exists by application of s47 or s47A NTA Pt Thurlga Native Title Status to be confirmed in ILUA Pastoral Lease Hundred of S82 Buckleboo Hundred of Pildappa Pastoral Lease Condada D59476A501 (portion) External Boundary of Determination Area Karcultaby Karcultaby Hundred of Hundred of Bungeroo 32°45'S PL 32°45'S NPWA Reserve Yeltana former former Pastoral -

Celebrating 25 Years of Across the Outback

April 2015 Issue 73 ACROSS THE OUTBACK Celebrating 25 years of 01 BOARD NEWS 02 Kids share what they love about their place Across The Outback 03 Act locally – join your NRM Group 04 Seasonal conditions report Welcome to the first edition of Across The Outback 05 LAND MANAGEMENT for 2015. 05 Commercial camel grazing This 73rd edition marks 25 years since The page is about natural resources on pastoral properties Across The Outback first rolled off the management in its truest sense – it’s 06 THREATENED SPECIES press as Outback, published by the about promoting healthy communities then Department of Lands on behalf and sustainable industries as much as 07 Idnya update of the Pastoral Board for the South environment and conservation news. 07 ABORIGINAL NRM NEWS Australian pastoral industry. Think community events, tourism 08 WATER MANAGEMENT The publication has seen changing news, information about road and covers and faces, and changes to park closures, and items for pastoralists 08 Sharing knowledge on the government and departments, but its on improving their (sustainable) Diamantina River Channel Country commitment to keep the SA Arid Lands production. 09 PEST MANAGEMENT community informed of government Continued on page 02… activities which affect them has 09 Buffel Grass declared in South Australia remained the same. And it remains the only publication 10 NRM GROUP NEWS that covers and centres on the SA Arid 12 PLANNING FOR WILD DOGS Lands region. Across The Outback is mailed to 14 NATIONAL PARKS about 1500 subscribers – through 14 A new management plan for email and via snail mail – and while Innamincka Regional Reserve its readership is many and varied, and includes conservation, recreation and 15 ANIMAL HEALTH tourist groups, its natural resources 16 OUTBACK COMMUNITY management focus has meant its core readership remains the region’s pastoral community. -

Data on Significant Wilderness Areas in the Alinytjara Wilurara and South Australian Arid Lands NRM Regions

Data on significant wilderness areas in the Alinytjara Wilurara and South Australian Arid Lands NRM Regions Wilderness Advisory Committee November 2014 Acknowledgments The Wilderness Advisory Committee acknowledges the invaluable work of the late Dr Rob Lesslie. His work forms the basis of much of this report, with the Wilderness Advisory Committee holding responsibility for the report. We thank the staff of the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources for their assistance, in particular Jason Irving and Ian Sellar. i | Data on significant wilderness areas in the Alinytjara Wilurara and South Australian Arid Lands NRM Regions Contents 1. Purpose of the report 1 2. The significance of wilderness 1 3. Wilderness surveys 3 4. Adequacy of formal protection 3 5. Management principles for the arid environment 4 6. Conclusion 5 Appendix 1. Wilderness Areas of Potential 6 National Significance: description Appendix 2. Climate change priority actions 26 Appendix 3 Maps 28 Map 1 Wilderness Areas of Potential 29 National Significance: Bioregions Map 2 Wilderness Areas of Potential 31 National Significance: Land Ownership Map 3 Wilderness Areas of Potential 33 National Significance: Watercourses and wetlands Map 4 Wilderness Areas of Potential 35 National Significance: Waterpoints Map 5 National Wilderness Inventory 37 Map 6 Wilderness Areas of Potential 39 National Significance: Conservation Area Type Map 7 Bioregional Distribution of Highly 41 Protected Areas (IUCN Category Ia, Ib, II and III) Map 8 Predicted Temperature Increase 42 for South Australia, 2030, 2050 and 2070 Data on significant wilderness areas in the Alinytjara Wilurara and South Australian Arid Lands NRM Regions | ii Left and right image: Nullabor Plains, South Australia 1. -

Full Programme of Abstracts and Biographies

AAANZ 2019 Ngā Tūtaki – Encounter/s: Agency, Embodiment, Exchange, Ecologies AAANZ Conference, Auckland, 3-6 December, 2019 Owen G. Glenn Building, The University of Auckland 12 Grafton Road, Auckland 1010 & Te Noho Kotahitanga Marae, Unitec Institute of Technology 139 Carrington Road, Mount Albert, Auckland 1025 & Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Corner Kitchener and Wellesley Streets, Auckland 1010 Full Programme of Abstracts and Biographies The AAANZ Conference 2019 is supported by the Te Noho Kotahitanga Marae, and the School of Architecture, Unitec Institute of Technology, Waipapa Marae, Elam School of Fine Arts and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Auckland, ST PAUL St Gallery and the Faculty of Design and Creative Technologies at Auckland University of Technology, Whitecliffe College of Art and Design, the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and the Chartwell Trust. The University of Auckland is proud to acknowledge Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei as mana whenua and the special relationship they have with the University of Auckland City Campus. Mana whenua refers to the iwi and hapū who have traditional authority over land. We respect the tikanga (customs) of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei as mana whenua and recognise their kaitiakitanga (stewardship) role over the land the City Campus is located on. 1 AAANZ 2019 Ngā Tūtaki – Encounter/s: Agency, Embodiment, Exchange, Ecologies NAU MAI HAERE MAI! Welcome to AAANZ 2019 Ngā Tūtaki – Encounter/s: Agency, Embodiment, Exchange, Ecologies in Tāmaki Makaurau! The theme for this year’s conference had as its starting point a critique of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage’s Tuia Encounters 250th commemorations taking place in Aotearoa in 2019: the notion of encounter was one to conjure with.