Bad Guys with Badges: a Vast Amount of Trouble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHEREAS, TMF As the Health Quality Institute

The State of Texas County of El Paso Know All Men By These Presents: WHEREAS, the last decade of the 19th Century saw El Paso and El Paso County labeled as the “Gun Fight Capital of the World.” As one of the last wide-open frontier communities, El Paso had the highest concentration of men with reputations with a gun; and, WHEREAS, on March 30th, 1895 the most famous gunman of them all, John Wesley Hardin arrived in El Paso to assist in prosecuting a case of attempted murder; and, WHEREAS, while serving in Huntsville for the murder of Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb, Hardin read law, and upon his pardon in 1894, passed the bar exam and was admitted to practice law in the State of Texas; and, WHEREAS, on the night of August 19th, 1895 Constable John Selman did shoot John Wesley Hardin as he played dice in the Acme Saloon on San Antonio Street, the body laying on the floor as many citizens of El Paso assembled to get a glimpse of the dead gunfighter; and, WHEREAS, John Wesley Hardin was buried at Concordia Cemetery, where his grave remains today, attracting tourists from around the world; and, WHEREAS, because of John Wesley Hardin, El Paso formed the first local Bar Association in the State of Texas in 1897, to prevent the likes of Hardin from practicing law in the county ever again. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED by the El Paso County Judge and Commissioners’ Court that true recognition be given that August 19th marks the 116th anniversary of the demise of famed Gunman, turned Attorney, John Wesley Hardin in El Paso. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Fort Bowie U.S

National Park Service Fort Bowie U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Bowie National Historic Site The Chiricahua Apaches Introduction The origin of the name "Apache" probably stems from the Zuni "apachu". Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of "nde", simply meaning "the people". By 1850, Apache culture was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and the Southwest, particularly the Pueblos, and as time progressed—Spanish, Mexican, and the recently arriving American settler. The Apache Tribes Chiricahua speak an Athabaskan language, relating Geronimo was a member of the Bedonkohe, who them to tribes of western Canada. Migration from were closely related to the Chihenne (sometimes this region brought them to the southern plains by referred to as the Mimbres); famous leaders of the 1300, and into areas of the present-day American band included Mangas Coloradas and Victorio. Southwest and northwestern Mexico by 1500. This The Nehdni primarily dwelled in northern migration coincided with a northward thrust of Mexico under the leadership of Tuh. the Spanish into the Rio Grande and San Pedro Valleys. Cochise was a Chokonen Chiricahua leader who rose to leadership around 1856. The Chockonen Chiricahuas of southern Arizona and New primarily resided in the area of Apache Pass and Mexico were further subdivided into four bands: the Dragoon Mountains to the west. Bedonkohe, Chokonen, Chihenne, and Nehdni. Their total population ranged from 1,000 to 1,500 people. Organization and Apache population was thinly spread, scattered of Apache government and was the position that Family Life into small groups across large territories, tribal chiefs such as Cochise held. -

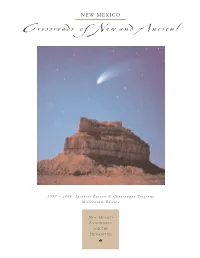

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

The SRAO Story by Sue Behrens

The SRAO Story By Sue Behrens 1986 Dissemination of this work is made possible by the American Red Cross Overseas Association April 2015 For Hannah, Virginia and Lucinda CONTENTS Foreword iii Acknowledgements vi Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Prologue Page One PART ONE KOREA: 1953 - 1954 Page 1 1955 - 1960 33 1961 - 1967 60 1968 - 1973 78 PART TWO EUROPE: 1954 - 1960 98 1961 - 1967 132 PART THREE VIETNAM: 1965 - 1968 155 1969 - 1972 197 Map of South Vietnam List of SRAO Supervisors List of Helpmate Chapters Behrens iii FOREWORD In May of 1981 a group of women gathered in Washington D.C. for a "Grand Reunion". They came together to do what people do at reunions - to renew old friendships, to reminisce, to laugh, to look at old photos of them selves when they were younger, to sing "inside" songs, to get dressed up for a reception and to have a banquet with a speaker. In this case, the speaker was General William Westmoreland, and before the banquet, in the afternoon, the group had gone to Arlington National Cemetery to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. They represented 1,600 women who had served (some in the 50's, some in the 60's and some in the 70's) in an American Red Cross program which provided recreation for U.S. servicemen on duty in Europe, Korea and Vietnam. It was named Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). In Europe it was known as the Red Cross center program. In Korea and Vietnam it was Red Cross clubmobile service. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

A Brave New World (PDF)

Dear Reader: In Spring 2005, as part of Cochise College’s 40th anniversary celebration, we published the first installment of Cochise College: A Brave Beginning by retired faculty member Jack Ziegler. Our reason for doing so was to capture for a new generation the founding of Cochise College and to acknowledge the contributions of those who established the College’s foundation of teaching and learning. A second, major watershed event in the life of the College was the establishment of the Sierra Vista Campus. Dr. Ziegler has once again conducted interviews and researched archived news paper accounts to create a history of the Sierra Vista Campus. As with the first edition of A Brave Beginning, what follows is intended to be informative and entertaining, capturing not only the recorded events but also the memories of those who were part of expanding Cochise College. Dr. Karen Nicodemus As the community of Sierra Vista celebrates its 50th anniversary, the College takes great pleas ure in sharing the establishment of the Cochise College Sierra Vista Campus. Most importantly, as we celebrate the success of our 2006 graduates, we affirm our commitment to providing accessible and affordable higher education throughout Cochise County. For those currently at the College, we look forward to building on the work of those who pio neered the Douglas and Sierra Vista campuses through the College’s emerging districtwide master facilities plan. We remain committed to being your “community” college – a place where teaching and learning is the highest priority and where we are creating opportunities and changing lives. Karen A. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Southern New Mexico Historical Review

ISSN 1076-9072 SOUTHERN NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW Pasajero del Camino Real Doña Ana County Historical Society Volume XV Las Cruces, New Mexico January 2008 Doña Ana County Historical Society Publisher Rick Hendricks Editor Board of Directors 2008 President: Roger Rothenmaier Vice President: George Helfrich Past President: Dr. Chuck Murrell Secretary: Donna Eichstaedt Treasurer: Xandy Church Historian: Karen George At Large Board Members Buddy Ritter Felix Pfaeffle Marcie Palmer Leslie Bergloff Frank Parrish Richard Majestic Barbara Jean Neal Mary Lou Pendergrass Ex-Officio: Webmaster – Mary Lou Pendergrass Liaison to Branigan Cultural Center – Garland Courts Typography and Printing Insta-Copy Imaging Las Cruces, New Mexico Cover Drawing by Jose Cisneros (Reproduced with permission of the artist) The Southern New Mexico Historical Review (ISSN-1076-9072) is looking for original articles concerning the Southwestern Border Region for future issues. Biography, local and family histories, oral history and well-edited documents are welcome. Charts, illustrations or photographs are encouraged to accompany submissions. We are also in need of book reviewers, proofreaders, and an individual or individuals in marketing and distribution. Copies of the Southern New Mexico Historical Review are available for $7.00. If ordering by mail, please include $2.00 for postage and handling. Correspon- dence regarding the Review should be directed to the Editor of the Southern New Mexico Historical Review at Doña Ana County Historical Society, 16045 Las Cruces, NM 88004. Click on Article to go There Table of Contents Articles Coeds at War: State College Woman Do Their Part in World War II Martha Shipman Andrews ..................................................................................... 1 William and John Hudgens: Double Trouble from Louisiana Roberta Key Haldane .......................................................................................... -

Hell on Wheels

MercantileEXCITINGSee section our NovemberNovemberNovember 2001 2001 2001 CowboyCowboyCowboy ChronicleChronicleChronicle(starting on PagepagePagePage 90) 111 The Cowboy Chronicle~ The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Shooting Society ® Vol. 21 No. 11 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. November 2008 . HELL ON WHEELS . THE SASS HIGH PLAINS REGIONAL By Captain George Baylor, SASS Life #24287 heyenne, Wyoming – The HIGHLIGHTS on pages 70-73 very name conjures up images of the Old West. chief surveyor for the Union Pacific C Wyoming is a very big state Railroad, surveyed a town site at with very few people in it. It has what would become Cheyenne, only 500,000 people in the entire Wyoming. He called it Cow Creek state, but about twice as many ante- Crossing. His friends, however, lope. A lady at Fort Laramie told me thought it would sound better as Cheyenne was nice “if you like big Cheyenne. Within days, speculators cities.” Cheyenne has 55,000 people. had bought lots for a $150 and sold A considerable amount of history them for $1500, and Hell on Wheels happened in Wyoming. For example, came over from Julesburg, Colorado— Fort Laramie was the resupply point the previous Hell on Wheels town. for travelers going west, settlers, and Soon, Cheyenne had a government, the army fighting the Indian wars. but not much law. A vigilance com- On the far west side of the state, mittee was formed and banishments, Buffalo Bill built his dream town in even lynchings, tamed the lawless- Cody, Wyoming. ness of the town to some extent. Cheyenne, in a way, really got its The railroad was always the cen- start when the South seceded from tral point of Cheyenne.