Burris Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017

Annual Report and Accounts 2016 / 2017 The Annual Report and Accounts are part of the Health Board’s public annual reporting and set out our service delivery, environmental and financial performance for the year and describe our management and governance arrangements. The Annual Governance Statement, which is provided as an Appendix to this document, forms part of the Accountability Report section of this Annual Report, and provides a detailed report on our governance, arrangements for managing risk and systems of internal control. The Annual Quality Statement, published separately, provides information on the quality of care across our services and illustrates the improvements and developments we have taken forward over the last year to continuously improve the quality of the care we provide. Copies of all these documents can be downloaded from the Health Board’s website at www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/861/page/40903 or are available on application to the Health Board’s Communications Team at BCUHB, Block 5, Carlton Court, St Asaph Business Park, St Asaph, LL17 0JG, by telephone on 01248 384776 or by e-mail to [email protected] . 2 “To improve health and provide excellent care” Contents Chairman's Foreword .................................................................................................................. 4 PART ONE - PERFORMANCE REPORT Overview ................................................................................................................................. 5 Chief Executive’s Statement .............................................................................................. -

Aubrey Lewis, Edward Mapother and the Maudsley

Aubrey Lewis, Edward Mapother and the Maudsley EDGAR JONES Aubrey Lewis was the most influential post-war psychiatrist in the UK. As clinical director of the Maudsley Hospital in Denmark Hill, London, and professor of psy- chiatry from 1946 until his retirement in 1966, he exercised a profound influence on clinical practice, training and academic research. Many junior psychiatrists, whom he had supervised or taught, went on to become senior clinicians and academics in their own right. Although not a figure widely known to the public (indeed, Lewis shunned personal publicity), he commanded respect in other medical disciplines and among psychiatrists throughout the world. A formidable and sometimes intimidating figure, he had a passion for intellectual rigour and had little patience with imprecision or poorly thought-out ideas. More than any other individual, Lewis was responsible for raising the status of psychiatry in the UK such that it was considered fit for academic study and an appropriate career for able and ambitious junior doctors. Comparatively little has been written of Aubrey Lewis's formative professional life, and, indeed, the Maudsley Hospital itself has been somewhat neglected by historians during the important interwar years. This essay is designed to address these subjects and to evaluate the importance of Edward Mapother not only in shaping the Maudsley but in influencing Lewis, his successor. The Maudsley Hospital The Maudsley Hospital was dfficially opened by the Minister of Health, Sir Arthur Griffith-Boscawen, on 31 January 1923.1 The construction had, in fact, been completed Edgar Jones, PhD, Institute of Psychiatry & Guy's King's and St Thomas' School of Medicine, Department of Psychological Medicine, 103 Denmark Hill, London SE5 8AZ. -

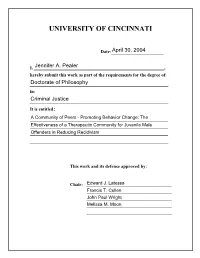

Complete Copy Pealer Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A COMMUNITY OF PEERS – PROMOTING BEHAVIOR CHANGE: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF A THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY FOR JUVENILE MALE OFFENDERS IN REDUCING RECIDIVISM A Dissertation Submitted to the: Division of Research and Advance Studies Of the University of Cincinnati In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) In the Division of Criminal Justice Of the College of Education April 2004 by Jennifer A. Pealer, M.A. B.A., East Tennessee State University, 1997 M.A., East Tennessee State University, 1999 Dissertation Committee: Edward J. Latessa, Ph.D. (Chair) Francis T. Cullen, Ph.D. John Paul Wright, Ph.D. Melissa M. Moon, Ph.D. A COMMUNITY OF PEERS – PROMOTING BEHAVIOR CHANGE: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF A THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY FOR JUVENILE MALE OFFENDERS IN REDUCING RECIDIVISM One avenue that has received considerable attention for the substance abusing adult population is a therapeutic community; however, research examining the effectiveness of this popular treatment modality for juveniles is scarce. While some studies have found a reduction in criminal behavior and substance abuse, others have found null results concerning the effectiveness of therapeutic communities. Furthermore, the literature on therapeutic communities has been criticized on the following points: 1) studies fail to incorporate multiple outcome criteria to measure program success; 2) follow-up time frames have been inadequate; 3) comparison groups often fail to account for important differences between groups that are likely to impact program outcome; and 4) insufficient attention that is given to the measure of program quality. -

Posted Online

Oral History Workshops: 1-80 The American Psychoanalytic Association, 1974-2018 Transcripts are missing for italicized workshops OHW # 1 Film Screening: Some Basic Concepts of Psychoanalysis May, 1974 and their Development: An Interview with Dr. Rene Spitz Denver, CO By Maria Piers Chair: Arcangelo D’Amore, OHW # 2 Psychoanalysis in Vienna, 1918-1939 December, 1974 Chair: Arcangelo D’Amore New York, NY Panelists: Sandor Lorand, and Richard Sterba Participants: M. Ralph Kaufman and Elise Pappenheim OHW # 3 Psychoanalysis Comes to the West Coast May 1975 Chair: Arcangelo D’Amore Los Angeles, CA Panelists: Douglass W. Orr, Ralph Greenson, Emanuel Windholz, Sigmund Gabe and Bernhard Berliner 1 OHW # 4 American Abroad: Psychoanalytic Training in Europe December, 1975 Before World War II New York, NY Chair: Sanford Gifford Panelists: Muriel Gardiner, Marie Briehl, Rosetta Hurwitz, Helen Tartakoff, Walter Langer (in absentia) OHW # 5 Psychoanalytic Education in the Eastern United States: May 1976 1911-1945 Baltimore, MD Panelists: Samuel Atkin, M. Ralph Kaufman, O. Spurgeon English, R.S. Bookhammer, Kenneth E. Appel, Douglas Noble, Sarah S. Tower and Helen Ross OHW # 6 European Refugee Psychoanalysts Come to the United December, 1976 States New York, NY Chair: Arcangelo D’Amore, Reporter: Robert J. Nathan Panelists: Edith Jacobson (New York), Edward Kronold, (New York), Bettina Warburg, (New York) Historical comments: Kurt R. Eissler and Martin Wangh 2 OHW # 7 Psychoanalysis in the Midwest April 1977 Chair: Frank H. Parcells, Coordinator: Douglas W. Orr Quebec Panelists: Harry E. August, Paul A. Dewald, Justin Krent Irwin C. Rosen and Brandt F. Steele OHW # 8 Research in Psychoanalysis in the United States, Part I December 1977 Drs. -

Draft - Site Development Brief

Draft - Site Development Brief Former North Wales Hospital Denbigh February 2014 Content 1. Introduction 4 2. Status and Stages in Preparation 4 3. Historic Background 4 4. Planning Policy and Conserving the Historic Environment 9 5. Site Description 11 6. Site Vision 13 7. Masterplan Framework 13 8. Access and Movement 16 9. Design Principles 16 10. Planning Obligations and Contributions towards Infrastructure 19 provision 11. Further Considerations 19 12. Contacts / Sources 21 Appendix 1: Planning History 22 Figure 1 Location of the Former North Wales Hospital Denbigh 3 Figure 2 Land at the Former North Wales Hospital in 1875 5 Figure 3 Land at the Former North Wales Hospital in 1899 6 Figure 4 Land at the Former North Wales Hospital in 1912 7 Figure 5 Land at the Former North Wales Hospital in 1967 8 Figure 6 Aerial view of the site development brief area in 2009 11 Figure 7 Masterplan 15 Picture 1 Rear view of original Hospital Building (Listed Building: Grade II*) 10 Picture 2 View towards the site from the junction of B4501 and Ystrad Road 12 Picture 3 Key historic building: former Chapel (Listed Building: Grade II) 17 - 2 - Figure 1: Location of the Former North Wales Hospital Denbigh - 3 - 1. Introduction 1.1 This site development brief is one of a series of Supplementary Planning Guidance notes (SPGs) amplifying Denbighshire Local Development Plan 2006 – 2021 (LDP) policies or principles of development for individual site allocations in a format which aims to guide the process, design and quality of new development. These notes are intended to offer detailed guidance to assist members of the public, Members of the Council, potential developers and Officers in discussions prior to the submission of and, consequently, in determination of future planning applications. -

Restore North Wales Hospital Denbighshire County Council To

P-04-381: Restore North Wales Hospital Denbighshire County Council to Deputy Clerk Dear Kayleigh, Thanks for your email. I've attached my last email to the petitioners which was shortly after the site visit by your Committee. You will note that I refer to previous correspondence with them but despite this they felt it necessary to submit a petition. Whenever they have contacted us we have responded quickly and as openly as possible. I have met them in a local pub with the local councillor to explain our strategy and future plans but despite all this they seem to misunderstand our intentions. Since the visit to the site by the Committee we have updated our own Cabinet, the local Members Area Group which comprises the County Councillors for the area and we have updated the Town Council in an open forum. We have commissioned a DVD which we use to inform members of the public. It was on a loop in the town library over the Open Heritage Weekend in September last year. We have now informed the owner of the hospital that it is our intention to serve a Repairs Notice and if not complied with we will begin compulsory purchase proceedings. The Urgent Works which were ongoing at the time of the Committee's visit are now completed. The total cost of these works were £930k. We are continuing with our efforts to save the building despite all the difficulties we face. Regards, Phil. Phil Ebbrell Pensaer Cadwraeth / Conservation Architect Gwasanaethau Cynllunio a Gwarchod y Cyhoedd /Planning and Public Protection Dear Mr Morales, Thank you for you email. -

William Pember Reeves, Writing the Fortunate Isles

WILLIAM PEMBER REEVES, WRITING THE FORTUNATE ISLES MEG TASKER Federation University, Ballarat In all its phases, the career of William Pember Reeves was shaped by overlapping social and cultural identities. From his childhood as an English migrant in New Zealand being groomed to join the colonial ruling class, to his advocacy of Greek independence and chairmanship of the Anglo-Hellenic League in his last decades, Reeves illustrates the kind of mobility across social as well as national and geographical borders that calls for the use of the term ‘transnational colonial’ rather than ‘expatriate.’1 He has this in common with many Australasian writers at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This paper will focus on how he ‘wrote New Zealand,’ particularly after his move to London in 1896 as Agent-General. The expression ‘transnational colonial,’ coined by Ken Gelder in relation to popular fiction (Gelder 1), conveys the cultural hybridity of the late nineteenth century Australasian abroad without imposing a rigidly ‘centre/margins’ structure of imperial power relations. The term ‘transnational’ stresses the existence of two-way or multiple exchanges of influences and ideas between colonial and metropolitan writers, publishers, readers, and markets. Such an approach to colonial/imperial cultural relationships has been developed by postcolonial critics and historians such as John Ball in Imagining London: Postcolonial Fiction and the Transnational Metropolis (2004), Angela Woollacott in To Try Her Fortune in London (2001), and Andrew Hassam, in Through Australian Eyes: Colonial Perceptions of Imperial Britain (2000). Similarly, in their excellent study of late colonial writing, Maoriland: New Zealand Literature 1872-1914, Jane Stafford and Mark Williams argue that ‘empire was an internationalising force in ways not often recognised. -

The Uncanny and Unhomely in the Poetry of RS T

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY '[A] shifting/identity never your own' : the uncanny and unhomely in the poetry of R.S. Thomas Dafydd, Fflur Award date: 2004 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 "[A] shifting / identity never your own": the uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas by Fflur Dafydd In fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The University of Wales English Department University of Wales, Bangor 2004 l'W DIDEFNYDDIO YN Y LLYFRGELL YN UNIG TO BE CONSULTED IN THE LIBRARY ONLY Abstract "[A] shifting / identity never your own:" The uncanny and the unhomely in the writing of R.S. Thomas. The main aim of this thesis is to consider R.S. Thomas's struggle with identity during the early years of his career, primarily from birth up until his move to the parish of Aberdaron in 1967. -

THE COUNCIL and OFFICERS, 1940 41. Officers. Non-Official Members

THE COUNCIL AND OFFICERS, 1940 41. Officers. President. —-THOMAS C. GRAVES, B.Sc., M.D., F.R.C.S. , T. LINDSAY, M.D., F.R.C.S.E., D.P.M. (South-Eastern). J. F. W. LEECH, B.A., M.D., B.C11., D.P.M. (South-Western). Vice-Presidents and H. D O VE COR.MAC, M.B., M.S., D.P.M. (S'orthern and Midland). Divisional Chairmen D. CHAMBERS, M.A., M.D., Ch.B., F.R.C.P.E. (Scottish). I C. B. MOLONEY, M B., Ch.B.N.U.L, D.P.M. (Irish). \ C. J. LODGE PATCH, -U.C., L. R.C.P.&S.Ed., L.R.F.P.S.Glas. (Indian). President-Elect.— A. A. W. PETRIE, M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.C.S.Eu. Ex-President.— A. HELEN BOYLE, M.D., L.R.C.I’.&S. Treasurer.— GEORGE WILLIAM SMITH, O .B.E., M.B. Hon. General Secretary.— W. GORDON MASEFIELD, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., D.P.M. Registrar.—H. G. L. HAYNES, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Hon. Librarian.— J . R. WHITYVELL, M.B. South-Eastern.— R. M. MACFARLANE, M.D., Ch.B., D.P.H., D.P.M. South-Western.— S. E. MARTIN, M.B. Divisional Northern and Midland.—J. IVISON RUSSELL, M.D., F.R.F.P.S.G. Secretaries '' < „ i J w - M- McALISTER, M.A., M.B., Ch.B., F.R.C.P.E. Secretaries , Scothsh. | c A CR1CHL 0 \V, M.B., Cn.B. Irish.—PATRICK MORAN, M.B., B.Ch., D.P.M. -

Michael Shepherd on Epidemiology in Psychiatry Leonardo Tondo

1 Programs (Interviews) December 24, 20155 Interviews with Pioneers Michael Shepherd On Epidemiology in Psychiatry Leonardo Tondo CONTENTS: Biographic sketch About the interview The Interview Endnotes Acknowledgements Biographical sketch Michael Shepherd (1923–1995) was born in Cardiff to a Jewish family originating in Odessa and Poland. He married Margaret Rock in 1947, who died in 1992, after a long illness. They had four children.1 He obtained his bachelor medical degree at the Oxford University, where he was influenced by John Ryle,2 a professor of social medicine, to pursue the social implications of mental disorders. In 1952, he started his career at the Maudsley Hospital and Institute of Psychiatry3 and obtained a doctorate in medicine from Oxford University, in 1954. In 1955–56, he trained at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore and visited several psychiatric centers in the United States to obtain material for a critical survey of American psychiatry.4 He documented a major difference in psychiatry in the US and UK as an emphasis on public services in the UK and dominant private office practice in the US. He noted 2 that “nearly 3,000 of the 7,500 recognised [American] psychiatrists in 1951–1952 listed private practice as their major activity…one-quarter of them were engaged in the practice of psychotherapy and were not considered to meet the traditional criteria of the practice of medicine.” Moreover, he found that American psychiatrists seemed to have a “distaste for the tracts of detailed knowledge dismissed -

Who Was Aubrey Lewis?

WHO WAS AUBREY LEWIS? Robert D Goldney AO, MD Emeritus Professor, Discipline of Psychiatry University of Adelaide Acknowledgements University of Adelaide personnel: Maureen Bell, Research Librarian Cheryl Hoskin, Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian Andrew Cook, Archives Officer Lee Kersten, Visiting Research Fellow in German Studies Obituaries/Biographies Australian Dictionary of Biography Michael Shepherd Brian Barraclough Edgar Jones David Goldberg Thomas Bewley “The man Adelaide forgot” The Advertiser, 10/3/90 “Had Aubrey Lewis gone to St Peter’s College and been interested in field sports his name would probably be well known to generations of South Australians. But he was Jewish, went to a catholic school, his father was a nobody and he lived up the East end of Rundle St – definitely the wrong side of the tracks for a prejudicial, parochial Adelaide of the 1920’s”. Foyer of Adelaide Medical school, 2016 Plaque presented 1981 Aubrey Lewis Born, Adelaide, 8 November 1900 Excelled at Christian Brothers College Adelaide University Medical graduate 1923 Anthropological Research with Wood Jones, 1925 Rockefeller Foundation fellowship 1926/27 Maudsley Hospital London, 1928 – 1966 MRCP 1928 Fellow 1938 MD (Adelaide) 1931 Clinical Director, Maudsley, 1936 Chair of Psychiatry 1946 Knighted 1959 – first psychiatrist Retired 1966 Died, London, 21 January 1975 CBC Literary Society “The judge specially complimented Master Aubrey Lewis, who, as an honorary member, made his first appearance, and, without notes of any kind, discussed Shakespeare -

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS in the UK in the 1960S

PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS IN THE UK IN THE 1960s Witness Seminar 11 October 2019 Claire Hilton and Tom Stephenson, convenors and editors 1 © Royal College of Psychiatrists 2020 This witness seminar transcript is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. Please cite this source as: Claire Hilton and Tom Stephenson (eds.), Psychiatric Hospitals in the UK in the 1960s (Witness Seminar). London: RCPsych, 2020. Contents Abbreviations 3 List of illustrations 4 Introduction 5 Transcript Welcome and introduction: Claire Hilton and Wendy Burn 7 Atmosphere and first impressions: Geraldine Pratten and David Jolley 8 A patient’s perspective: Peter Campbell 16 Admission and discharge: 20 Suzanne Curran: a psychiatric social work perspective Professor Sir David Goldberg: The Mental Health Act 1959 (and other matters) Acute psychiatric wards: Malcolm Campbell and Peter Nolan 25 The Maudsley and its relationship with other psychiatric hospitals: Tony Isaacs and Peter Tyrer 29 “Back” wards: Jennifer Lowe and John Jenkins 34 New roles and treatments: Dora Black and John Hall 39 A woman doctor in the psychiatric hospital: Angela Rouncefield 47 Leadership and change: John Bradley and Bill Boyd 49 Discussion 56 The contributors: affiliations and biographical details