Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panel Survey

UK Data Archive Study Number 1614 - British Election Study, 1974, 1975, 1979: Panel Survey THE BRITISH ELECTION STUDY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX 3 mrRomoN The Bmtish Electlm Studyhaa threegemral amra: (a) the pmw..sionof an accurate,comprehensive,histomcal recordof tie att~ttiesand behamour of tie Brntlshelectorateat the GeneralEkctIms; (b) tie studyof long-termpahtlcal and electoralchangein Britain,.md (c) tie cmtinkd accmulatim of a data archiveon the po~tmal atiitudes and behatiourof the Britishelectors= over tim for the benefitof tie academicccmmNNty at large. Afterthe GeneralElectlm.sof Februaryand Octcber1974 the British Ele&on Study conductedfour mtemsw surveys. These surveysestabhshed five sepmate smples of electors:(1) a samplemtervie=d aftertie electronsof June 1970 and February1974; (2) a representatlwcmss- sectmn sanpleinterviewedaftertie electlcnof February1974; (3) a representativeCress-sectmnsamplemterwiewe~ aftertie ekction of Oct&er l!l74, (4) a panel sarplemtermewed afterboth tie 1974 el.ectlons, (5) a spemal Scottishsanplemtervmwed after tie electlm of Octcber1974. A total of a?umzt5,003ltividuals M urmlved in all thesesan’pies. Amng the speclflcthems exploredwere: the magnitudeand @roes of tie eroslm of erdu’mg supportfor tie two m] or parties,the dmngmg rela~cmhlp betweensccials~atlflcatim and electoml behamour; ad changesm the supportsecuredby tie m] or partiesas a resultof short- tenn factors,espaally issues. In cm] unc’honwith tie electlonstuckesthe Essex team also conducteda pstal surwy aftertie Referendm m Jme 1975. 1 4 The 1970 - February1974 PanelSurvey The samplefor Um surveywas mterlted frctntie 1970 Butlerend Stokes electlonstudy. OrI@nally 30 mnstituencleshad been selectedwith probabill~ prqmrtlonateto size of electoratefrcm a hst of 613 consti+menmesthroughout@at Bmtam (excludingNorthernIrelandand omstituenaes mrth of tie Caledcrum Canal). -

LPM No 20 (PDF)

Labour Party Marxists labourpartymarxists.org.uk Free - donations welcome James Linney denounces the the Tories and their ongoing programme of privatisation uly 5 marks 70 years since the reported to have cut care packages for NHS at 70 foundation of the national health seriously ill children.After failing to secure service, but anyone who values the a contract to provide children’s health principle of healthcare provision services across Surrey, worth £82 million, Jthat is free of the influence of profit will Virgin also decided to sue the local clinical surely feel little enthusiasm to join the commissioning groups - the NHS settled official celebrations: open days, high out of court for an undisclosed amount, street exhibitions, staff awards, glittering said to be in the millions of pounds. services at Westminster Abbey and York Suing an already crisis-ridden NHS is Minster. In fact the NHS’s 70th year has bad enough, but this is nothing compared possibly been the most difficult since its to the potential harm that would result creation in 1948. from a health company like Virgin pulling Yet, as the suffering of those people out of an ACO if it was deemed no longer who use the NHS, or are employed by it, profitable or if the company collapsed. multiplied during another harsh winter, Despite his talent for accumulating vast there are noticeably some who will be sums of money for himself, Richard celebrating; because for them that suffering Branson has left plenty of failed business is simply an opportunity to open the NHS ventures in his wake: Virgin Cola, Virgin up to greater privatisation. -

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report Investigationreport April 2018

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale and Rochdale View Knowl House, Cambridge Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report Investigation ReportInvestigation April 2018 HC 954-III 2018 Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 25 April 2018 A report of the Inquiry Panel HC 954-III © Crown copyright 2018 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] or Freepost IICSA INDEPENDENT INQUIRY. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications ISBN 978-1-5286-0290-7 CCS0318279676 04/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Executive Summary iii Images, maps and plans vii Part A: Introduction 1 The background to the investigation 2 Cyril Smith 3 Knowl View School 5 Reasons for investigating Rochdale and issues considered 8 Standards and terminology -

The Culture of Queers

THE CULTURE OF QUEERS For around a hundred years up to the Stonewall riots, the word for gay men was ‘queers’. From screaming queens to sensitive vampires and sad young men, and from pulp novels and pornography to the films of Fassbinder, The Culture of Queers explores the history of queer arts and media. Richard Dyer traces the contours of queer culture, examining the differ- ences and continuities with the gay culture which succeeded it. Opening with a discussion of the very concept of ‘queers’, he asks what it means to speak of a sexual grouping having a culture and addresses issues such as gay attitudes to women and the notion of camp. Dyer explores a range of queer culture, from key topics such as fashion and vampires to genres like film noir and the heritage film, and stars such as Charles Hawtrey (outrageous star of the Carry On films) and Rock Hudson. Offering a grounded historical approach to the cultural implications of queerness, The Culture of Queers both insists on the negative cultural con- sequences of the oppression of homosexual men and offers a celebration of queer resistance. Richard Dyer is Professor of Film Studies at The University of Warwick. He is the author of Stars (1979), Now You See It: Studies in Lesbian and Gay Film (Routledge 1990), The Matter of Images (Routledge 1993) and White (Routledge 1997). THE CULTURE OF QUEERS Richard Dyer London and New York First published 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Candidates West Midlands

Page | 1 LIBERAL/LIBERAL DEMOCRAT CANDIDATES in PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS in the WEST MIDLAND REGION 1945-2015 ALL CONSTITUENCIES WITHIN THE COUNTIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE SHROPSHIRE STAFFORDSHIRE WARWICKSHIRE WORCESTERSHIRE INCLUDING SDP CANDIDATES in the GENERAL ELECTIONS of 1983 and 1987 COMPILED BY LIONEL KING 1 Page | 2 PREFACE As a party member since 1959, based in the West Midlands and a parliamentary candidate and member of the WMLF/WMRP Executive for much of that time, I have been in the privileged position of having met on several occasions, known well and/or worked closely with a significant number of the individuals whose names appear in the Index which follows. Whenever my memory has failed me I have drawn on the recollections of others or sought information from extant records. Seven decades have passed since the General Election of 1945 and there are few people now living with personal recollections of candidates who fought so long ago. I have drawn heavily upon recollections of conversations with older Liberal personalities in the West Midland Region who I knew in my early days with the party. I was conscious when I began work, twenty years ago, that much of this information would be lost forever were it not committed promptly to print. The Liberal challenge was weak in the West Midland Region over the period 1945 to 1959 in common with most regions of Britain. The number of constituencies fought fluctuated wildly; 1945, 21; 1950, 31; 1951, 3; 1955 4. The number of parliamentary constituencies in the region averaged just short of 60, a very large proportion urban in character. -

1 the UNIVERSITY of HULL Power and Persuasion: the London West India Committee, 1783-1833 Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Power and Persuasion: The London West India Committee, 1783-1833 Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Hull by Angelina Gillian Osborne BA (American International College) MA (Birkbeck College, University of London) September 2014 1 Abstract In 1783 the West India interest – absentee planters, merchants trading to the West Indies and colonial agents - organised into a formal lobbying group as a consequence of the government’s introduction of colonial and economic policies that were at odds with its political and economic interests. Between 1783 and 1833, the London West India Committee acted as political advocates for the merchant and planter interest in Britain, and the planters residing in the West Indies, lobbying the government for regulatory advantage and protection of its monopoly. This thesis is a study of the London West India Committee. It charts the course of British anti-abolition through the lens of its membership and by drawing on its meeting minutes it seeks to provide a more comprehensive analysis of its lobbying strategies, activities and membership, and further insight into its political, cultural and social outlook. It explores its reactions to the threat to its political and commercial interests by abolitionist agitation, commercial and colonial policy that provoked challenges to colonial authority. It argues that the proslavery position was not as coherent and unified as previously assumed, and that the range of views on slavery and emancipation fractured consensus among the membership. Rather than focus primarily on the economic aspects of their lobbying strategy this thesis argues for a broader analysis of the West India Committee’s activities, exploring the decline of the planter class from a political perspective. -

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018 2018 Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018 Report of the Inquiry Panel © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernment-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.iicsa.org.uk. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. Contents Executive Summary iii Images, maps and plans vii Part A: Introduction 1 The background to the investigation 2 Cyril Smith 3 Knowl View School 5 Reasons for investigating Rochdale and issues considered 8 Standards and terminology 10 References 10 Part B: Cambridge House 11 Background and Cyril Smith’s involvement 12 Allegations made to Lyndon Price in 1965 16 The Lancashire Constabulary investigation 1969–70 17 The Director of Public Prosecutions 20 The office and powers of the Director of Public Prosecutions in 1970 20 The decision of the Director of Public Prosecutions 21 The 1979 Rochdale Alternative Paper articles 25 The Director of Public Prosecutions and the press in 1979 28 Cyril Smith’s knighthood 30 The decisions by the Crown Prosecution Service in 1998 and 1999, and the review in 2012 32 The Greater Manchester Police investigation 1998–99 35 Local rumours -

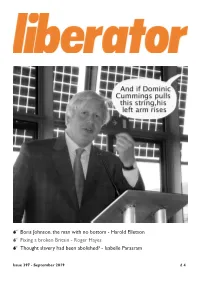

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

Jo Grimond: an Appreciation Jo Grimond Brought the Liberal Party Back from the Brink of Extinction

Jo Grimond: an appreciation Jo Grimond brought the Liberal Party back from the brink of extinction. Michael Meadowcroft, former MP for Leeds West, who worked for Grimond in the 1960s, remembers the man and his achievements. Leaving aside any additional influence from his The death of Jo Grimond on 24th October had a marriage into the Asquith family, the answer was to curious impact on friend and opponent alike. For Liberals who lived through the heady days of Jo's be found in a succinct phrase of another Liberal candidate of the period: "We couldn't stand the leadership his affectionate obituaries were more than a tribute to the man. In reality the Grimond era had Tories and we didn't trust the state." In many long since passed but, whilst its figurehead was still respects this is the constant thread of all Jo's writing around, part of one's mind had somehow retained a and places him in the direct succession to T H Green, sense of connection and a willing self deceit that his Maynard Keynes, ~amsa~Muir and Elliott Dodds. As period of leadership was somehow far more recent for the leadership question, one must not mistake Jo's than it was. Jo's death brings a sense of sad finality mischievous self-deprecation for humility: he had to a vivid chapter of political history. The words and considerable vanity and never appeared to lack faith in ideas remain on the page but, much more than with his ability to recreate a relevant Liberal Party. There most leaders, it was the spark of the personality is even a sense in which, for all the many 1970s behind them that gave them the added inspiration that Liberals' regrets that he was before his time, he would causes many fifty pluses still to call themselves have found the later Liberal Party more difficult to "Grimond Liberals". -

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018

Cambridge House, Knowl View and Rochdale Investigation Report April 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 25 April 2018 A report of the Inquiry Panel HC 954-III © Crown copyright 2018 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] or Freepost IICSA INDEPENDENT INQUIRY. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications ISBN 978-1-5286-0290-7 CCS0318279676 04/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Executive Summary iii Images, maps and plans vii Part A: Introduction 1 The background to the investigation 2 Cyril Smith 3 Knowl View School 5 Reasons for investigating Rochdale and issues considered 8 Standards and terminology 10 References 10 Part B: Cambridge House 11 Background and Cyril Smith’s involvement 12 Allegations made to Lyndon Price in 1965 16 The Lancashire Constabulary investigation 1969–70 17 The Director of -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

MINOR: j!", MINOR: j!", 'A4 x 14, ................... LP lit, fn Al, Northwestern University Library Evanston, Illinois 60201 Ott1 L SOUTH AFRICA AT WAR SOUTH AFRICA AT WAR White Power and the Crisis in Southern Africa RICHARD LEONARD LAWRENCE HILL & COMPANY WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT 06880 To the memory of my father Copyright © 1983 by Richard Leonard All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by Lawrence Hill & Company, Publishers, Inc. 520 Riverside Avenue Westport, Connecticut 06880 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Leonard, Richard. South Africa at war. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. South Africa-Race relations. 2. South AfricaPolitics and government-1961- 1978. 3. South AfricaPolitics and government-1978- . 4. South AfricaForeign relations-1961- . 5. Guerrillas-South Africa. 6. Guerrillas-Africa, Southern. 7. Africa, Southern-Politics and government-1975I. Title. DT763.L46 1983 305.8'00968 82-23405 ISBN 0-88208-108-X ISBN 0-88208-109-8 (pbk.) 123456789 Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgments x 1 From Police Repression to Military Power 3 2 The Black Struggle for Freedom 21 3 The War in Namibia and Regional Aggression 59 4 Military, Police, and Security Forces 98 5 Arms for Apartheid 131 6 The Propaganda War 161 7 The Total Strategy 198 8 The Crisis in American Policy 222 Appendix A The Freedom Charter 242 Appendix B Secret Propaganda Projects 245 Appendix C The Crocker Documents 248 Notes 261 Index 275 Preface For decades there have been warnings that South Africa is a tinderbox, ready to explode in a racial conflagration. -

Chiswick Book Festival

CHISWICK BOOK FESTIVAL MAKE A LONG WEEKEND OF IT 14-18 SEPTEMBER 2017 St Michael and All Angels Church and Parish Hall, Bath Road, London, W4 1TX, by Turnham Green tube station Other venues include Chiswick House, Chiswick Library, The Tabard Theatre (and pub), Ginger Whisk and the Andrew Clare Balding David Baddiel Cathy Rentzenbrink Lloyd Webber Foundation Theatre at the Arts Educational Schools (ArtsEd) John O’Farrell Jo Malone Nicholas Crane Director: Torin Douglas Author Programme Director: Jo James Production Manager: Vicky Taylor Festival Co-ordinator: Victoria Morley St Michael & Angels Jeremy Vine Hunter Davies Parish Office, W4 1TX www.chiswickbookfestival.net [email protected] Jeremy Vine Maggie O’Farrell Hunter Davies Follow us @W4BookFest and #ChiswickBookFest. Book now and see full updated programme at www.chiswickbookfestival.net WELCOME TO THE CHISWICK BOOK FESTIVAL 2017 PRE-FESTIVAL EVENTS th The 9 Chiswick Book Festival brings together top authors and their readers for an inspiring and entertaining Tuesday 12 September, long weekend of fiction, history, politics, memoir, crime, gardening, music, food, wine, the environment, 11am, The Happy Birth workshops, children’s books & more. Book - Beverley Turner Since 2009, the Chiswick Book Festival has raised more than £60,000 for charities which support reading Join LBC’s Beverley and literacy and for St Michael & All Angels Church, which hosts the Festival. This year the Festival will Turner (seen here continue to support: with husband James Cracknell at the launch RNIB Talking Books Service and Books for Children, supporting blind and partially sighted people. The of The Happy Birth Book) Festival has sponsored the recording of many Talking Books, including The Story of My Life by Helen Keller, and a panel of experts Parade’s End by Ford Madox Ford and Keeping On, Keeping On by Alan Bennett.