Report on Work with the Bamum Script in Cameroon Source: Bamum Scripts & Archives Project, Charles Riley Date: 2006-09-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 by Ellen Ndeshi Namhila 1. Africa Has a Rich and Unique Oral

THE AFRICAN PERPECTIVE: MEMORY OF THE WORLD By Ellen Ndeshi Namhila1 PREPARED FOR UNESCO MEMORY OF THE WORLD 3RD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA 19 TO 22 FEBRUARY 2008 1. INTRODUCTION Africa has a rich and unique oral, documentary, musical and artistic heritage to offer to the world, however, most of this heritage was burned down or captured during the wars of the scramble for Africa, and what had survived by accident was later intentionally destroyed or discontinued during the whole period of colonialism. In spite of this, the Memory of the World Register has so far enlisted 158 inscriptions from all over the world, out of which only 12 come from 8 African countries2. Hope was restored when on 30th January 2008, the Africa Regional Committee for Memory of the World was formed in Tshwane, South Africa. This paper will attempt to explore the reasons for the apathy from the African continent, within the framework of definitions and criteria for inscribing into the register. It will illustrate the breakdown and historical amnesia of memory and remembrance of the African heritage within the context of colonialism and its processes that have determined what was considered worth remembering as archives of enduring value, and what should be forgotten deliberately or accidentally. The paper argues that the independent African societies emerging from the colonial regimes have to make a conscious effort to revive their lost cultural values and identity. 2. A CASE STUDY: THE RECORDS OF BAMUM African had a rich heritage, well documented and well curated long before the Europeans came to colonise Africa. -

Universal Scripts Project: Statement of Significance and Impact

Universal Scripts Project: Statement of Significance and Impact The Universal Scripts Project expands the capabilities of the Internet by providing digital access to text materials from a variety of modern and historical cultures whose writing systems are not currently included in the international standard for electronic representation of scripts, known as Unicode. People who write in these scripts find it difficult to use email, compose and send documents electronically, and post documents on the World Wide Web, without relying on nonstandard fonts or other cumbersome workarounds, and are therefore left out of the “technological revolution.” About 66 scripts are currently included in the Unicode standard, but over 80 are not. Some 40 of these missing scripts belong to modern linguistic minorities in Africa, the Indian subcontinent, China, and other countries in Southeast Asia; about 40 are scripts of historical importance. The project’s goal for 2007–2008 is to provide the standards bodies overseeing character sets with proposals for 15 scripts to be included in the Unicode standard. The scripts selected for inclusion include 9 modern minority scripts and 6 historical scripts. The need is urgent, because the entire process, from first proposal to acceptance, typically takes from 2 to 5 years, and support among corporations and national bodies for adding more scripts to Unicode is uncertain. If the proposals are not submitted soon, these user communities will not be able to use their scripts in the near future. The scripts selected for this grant have established scholarly and user-community connections, which will help guarantee that the proposals meet the users' needs. -

A History of Language

A History of Language STEVENROGERFISCHER a history of language globalities Series editor: Jeremy Black globalities is a series which reinterprets world history in a concise yet thoughtful way, looking at major issues over large time-spans and political spaces; such issues can be political, ecological, scientific, technological or intellectual. Rather than adopting a narrow chronological or geographical approach, books in the series are conceptual in focus yet present an array of historical data to justify their arguments. They often involve a multi-disciplinary approach, juxtaposing different subject-areas such as economics and religion or literature and politics. In the same series Why Wars Happen Jeremy Black A History of Language steven roger fischer reaktion books Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 79 Farringdon Road, London ec1m 3ju, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 1999, reprinted 2000 First published in paperback 2001 Copyright © Steven Roger Fischer, 1999 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in Great Britain by St Edmundsbury Press, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: Fischer, Steven R. A history of language. – (Globalities) 1. Linguistic change 2. Sociolinguistics 3. Linguistic change – Social aspects I. Title 417.7 isbn 1 86189 051 6 (hbk) 1 86189 080 x (pbk) Contents preface 7 1 Animal Communication and ‘Language’ 11 2 Talking Apes 35 3 First Families 60 4 Written Language 86 5 Lineages 112 6 Towards a Science of Language 139 7 Society and Language 172 8 Future Indicative 204 references 221 select bibliography 232 index 236 Preface This book is an introduction to a history of language. -

Vai (Also Vei, Vy, Gallinas, Gallines) Is a Western Mande Langu

Distribution of complexities in the Vai script Andrij Rovenchak1, Lviv Ján Mačutek2, Bratislava Charles Riley3, New Haven, Connecticut Abstract. In the paper, we analyze the distribution of complexities in the Vai script, an indigenous syllabic writing system from Liberia. It is found that the uniformity hypothesis for complexities fails for this script. The models using Poisson distribution for the number of components and hyper-Poisson distribution for connections provide good fits in the case of the Vai script. Keywords: Vai script, syllabary, script analysis, complexity. 1. Introduction Our study concentrates mainly on the complexity of the Vai script. We use the composition method suggested by Altmann (2004). It has some drawbacks (e. g., as mentioned by Köhler 2008, letter components are not weighted by their lengths, hence a short straight line in the letter G contributes to the letter complexity by 2 points, the same score is attributed to each of four longer lines of the letter M), but they are overshadowed by several important advantages (it is applicable to all scripts, it can be done relatively easily without a special software). And, of course, there is no perfect method in empirical science. Some alternative methods are mentioned in Altmann (2008). Applying the Altmann’s composition method, a letter is decomposed into its components (points with complexity 1, straight lines with complexity 2, arches not exceeding 180 degrees with complexity 3, filled areas4 with complexity 2) and connections (continuous with complexity 1, crisp with complexity 2, crossing with complexity 3). Then, the letter complexity is the sum of its components and connections complexities. -

The Invention, Transmission and Evolution of Writing

THE INVENTION, TRANSMISSION AND EVOLUTION OF WRITING: INSIGHTS FROM THE NEW SCRIPTS OF WEST AFRICA Note to editors: • Please install the following fonts: Dukor (http://www.evertype.com/fonts/vai/); New Gardiner (https://mjn.host.cs.st- andrews.ac.uk/egyptian/fonts/newgardiner.html) • Both maps require minor revisions. Map 1: Bamum label should be ca. 1896- 1910; Map 2: Bamum label should be ca. 1896-1910 and Kikakui label should be ca. 1917. I will supply revised maps as soon as I can. ABSTRACT West Africa is a fertile zone for the invention of new scripts. As many as twenty-seven have been devised since the 1830s (Dalby 1967, 1968, 1969; Rovenchak, Glavy 2011, inter alia) including one created as recently as 2010 (Ibekwe 2012, 2016). Talented individuals with no formal literacy are likely to have invented at least three of these scripts, suggesting that they had reverse-engineered the ‘idea of writing’ on the same pattern as the Cherokee script, i.e. with minimal external input. Influential scholars like E. B. Tylor, A. L. Kroeber and I. J. Gelb were to approach West African scripts as naturalistic experiments in which the variable of explicit literacy instruction was eliminated. Thus, writing systems such as Vai and Bamum were invoked as productive models for theorising the dynamics of cultural evolution (Tylor [1865] 1878, Crawford 1935, Gelb [1952] 1963), the diffusion of novel technologies (Crawford 1935, Kroeber 1940), the acquisition of literacy (Forbes 1850, Migeod 1911, Scribner and Cole 1981) the cognitive processing of language (Kroeber 1940, Gelb [1952] 1963), and the evolution of writing itself (Crawford 1935, Gelb [1952] 1963; Dalby 1967, 2). -

Writing in Indigenous African Scripts: from Satzschrift to Alphabet

Writing in Indigenous African Scripts: from Satzschrift to Alphabet Andrij Rovenchak (Lviv) New inventions of writing within indigenous societies constitute an interesting phenomenon. In most cases new scripts can be classified as “individual writing systems” rarely expanding beyond a closed circle of friends and relatives. However, even such scripts can show non-standard approaches to the way the language is reduced to writing, as the one-to-one mapping with an existing official orthography is practically never observed. An overview of scripts used in the Sub-Saharan Africa is planned. This region is known for numerous attempts to introduce new orthographies in modern times, starting from the Vai script which originated in the 1820s (Dalby 1967). All the script types are attested here, from the so called sentence (phrase) writing or Satzschrift (Meinhof 1911) to alphabets. Majority of scripts are syllabaries, which can be in particular explained by phonotactics of the respective languages. Numerous graphical systems can be classified as sentence writing, where a symbols corresponds to some proverb, statement, or even a short story. Such (in fact, proto-writings) include Adinkra, Nsibidi, Nlo (Ewe proverbs), Sona, etc. (cf. Kubik 1986, Tuchscheree 2007). Often, they are linked to some secret societies and the meaning of signs is not fully known by non-initiates. , Ge‘ez ,أبجد Indigenous naming of scripts either reflects some standard recitation order (cf. Arabic Greek αλφάβητο, English ABC, Polish abecadło, Ukrainian абетка, etc.) or a special name is given based on various considerations. Examples of the first group include: A-ja-ma-na for the Vai syllabary, Ki-ka-ku-i for the Mende syllabary, Ma-sa-ba for the Bambara syllabary (Galtier 1987), A-ka-u-ku for the Bamum script. -

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3306 - Roadmap Snapshot

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3306 - Roadmap Snapshot INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3306 2007-08-29 Title: Snapshot of Pictorial view of Roadmaps to BMP, SMP, SIP and SSP Ad hoc group on Roadmaps (Michael Everson, Rick McGowan, and Ken Whistler) Source: Adapted by: V.S. Umamaheswaran Status: For review and adoption by WG 2 at its meeting M51 Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2, ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 and Liaison Organizations Replaces: JTC 1/SC 2/ WG 2/ N3228 Summary This document is the latest snapshot of the roadmap documents that has been presented to and adopted by WG 2 (ISO/IEC JTC1/ SC2/WG 2). Four tables containing the roadmaps to ● the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP - Plane 0) (version bmp-5-0-5, 2007-08-22) ● the Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP - Plane 1) (version smp-5-0-5, 2007-08-29) ● the Supplementary Ideographic Plane (SIP - Plane 2) (version sip-5-0-1, 2006-09-29), and ● the Supplementary Special-purpose Plane (SSP - Plane 14) (version ssp-5-0, 2006-09-21) are included in this document. The Roadmap ad hoc group maintains and updates the roadmaps as a service to the UTC (Unicode Technical Committee) and to ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. The latest working version of the roadmaps can be found at http://www.unicode.org/roadmaps. This document is informative. Please send corrigenda and other comments to the authors using the online contact form. -

WRITING AS a REFLECTION of the CIVILIZATION from ANTIQUITY to the MODERN TIMES Andrij ROVENCHAK, Associate Professor, Ph.D

WRITING AS A REFLECTION OF THE CIVILIZATION FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE MODERN TIMES Andrij ROVENCHAK, Associate Professor, Ph.D. (Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Ukraine) Abstract In the paper, a short discussion on the role of writing in the history of humanity is presented. The origins of writing are analyzed and some facts of modern script inventions are found to confirm its two-fold nature, both from economical (trade) and spiritual (religious) needs. Similar development of writing in different world regions and identical internal structure of logographic scripts can be the evidence for the universality of human thinking. A correlation between the types of civilization and the “philosophy” of writing is pointed. Keywords: writing, civilization, Antiquity, modern times. Rezumat În articol, este abordat rolul scrisului în istoria omenirii. Originea scrisului este analizată de rând cu unele inovaţii contemporane în acest domeniu pentru a demonstra caracterul biaspectual al acestuia, motivat atât de necesităţile economice (comerciale), cât şi de cele spirituale (religioase). Evoluţia similară a sistemelor de scriere în diferite regiuni ale lumii şi structura internă identică a logografurilor pot fi dovada universalităţii gândirii umane. Se pune accentul şi pe corelaţia dintre tipurile de civilizaţie şi filozofia scrisului. Cuvinte-cheie: scris, civilizaţie, Antichitate, modernitate. 1. Origins of Writing Writing systems are generally believed to be successors of the so-called proto-writing, i. e., early ideographic or mnemonic symbols. The following world regions can be listed as independent birthplaces of writing: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Indus Valley, China, Crete and Mesoamerica. 1.1. Mesopotamia Sumerian cuneiform is probably the most ancient known writing. -

Comparative Perspectives on the Study of Script Transfer, and the Origin of the Runic Script

Comparative Perspectives on the Study of Script Transfer, and the Origin of the Runic Script Corinna Salomon Abstract. The paper discusses a series of cases of script transfer with regard to the role played by script inventors in an effort to determine whether a premise held by certain scholars in runology, viz. that scripts are always created by indi- viduals, is warrantable. 1. Preliminary Remarks When setting out to research the derivation of the Runic script, the scholar soon finds that—even considering the appeal that is particular to questions about first beginnings and origins—the amount of litera- ture dedicated to this problem exceeds expectations. Making this ob- servation is in fact a commonplace of runology, serving as introduction to numerous studies concerned with the issue. Die frage nach dem alter und dem ursprung der runen ist so oft aufgewor- fen und auf so viele verschiedene weisen beantwortet worden, daſs man fast versucht sein könnte zu sagen, daſs alle möglichen, denkbaren und undenk- baren ansichten zu worte gekommen sind. […] Es ist eine sehr groſse literatur, die hier vorliegt; aber die qualität steht leider im umgekehrten verhältnis zur quantität.1 This paper represents a slightly reworked section of my doctoral thesis Raetic and runes. On the North Italic theory of the origin of the Runic script (University of Vienna 2018). Corinna Salomon 0000-0001-7257-6496 Institut für Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Wien, Sensengasse 3a, 1090 Wien, Austria E-mail: [email protected] 1. “The question of the age and the origin of the runes has been asked so often and answered in so many different ways that one might almost be tempted to say that all possible, plausible and absurd views have been heard. -

Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2 N 3976R Date: 2007-10-03

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N 3976R DATE: 2007-10-03 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 Coded Character Sets Secretariat: Japan (JISC) DOC. TYPE Disposition of Comments Disposition of Comments Report on SC 2 N 3940, ISO/IEC 10646: 2003/PDAM 5, Information technology -- Universal Multiple-Octet TITLE Coded Character Set (UCS) -- AMENDMENT 5: Meitei Mayek, Bamum, Tai Viet, Avestan, Egyptian Hieroglyphs, CJK Unified Ideographs Extension C, and other characters [WG2N3345R] SOURCE ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROJECT JTC1.02.10646.00.05 Disposition of comments approved at the 51st WG 2 meeting. This STATUS document is circulated to the SC 2 members for information. ACTION ID FYI DUE DATE P, O and L Members of ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 ; ISO/IEC JTC 1 DISTRIBUTION Secretariat; ISO/IEC ITTF ACCESS LEVEL Def ISSUE NO. 288 NAME 02n3946r.pdf SIZE FILE (KB) 16 PAGES Secretariat ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 - IPSJ/ITSCJ (Information Processing Society of Japan/Information Technology Standards Commission of Japan)* Room 308-3, Kikai-Shinko-Kaikan Bldg., 3-5-8, Shiba-Koen, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0011 Japan *Standard Organization Accredited by JISC Telephone: +81-3-3431-2808; Facsimile: +81-3-3431-6493; E-mail: kimura @ itscj.ipsj.or.jp ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 3345R Date: 2007-10-02 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Coded Character Set Secretariat: Japan (JISC) Doc. Type: Disposition of comments Title: Disposition of comments on SC2 N 3940 (PDAM text for Amendment 5 to ISO/IEC 10646:2003) Source: Michel Suignard (project editor) Project: JTC1 02.10646.00.05 Status: For review by WG2 Date: 2007-10-02 Distribution: WG2 Reference: SC2 N3940, 3959 Medium: Paper, PDF file Comments were received from China, Germany, India, Iran, Ireland, Japan, Korea, United Kingdom, and USA. -

African Writing Systems

African Writing Systems Mandombe script Writing is a means by which people record, objectify, and organize their activities and thoughts through images and graphs . Writing is a means to inscribe meanings that are expressed through sounds. Further, writing provides an aspect of historicality. [1] This means that writing facilitates the proper recording and transmissions of events and deeds from one generation to another. Most of the worlds written script originated from the Semitic script. The Greeks converted the Semitic script into what was to become the 'English script' of the western world. Arabic and Hebrew retained the basic format of the Semitic script, employing vowel characters and not letters. Chinese script developed uniquely. It is rather interesting to note that no alphabet is known to have ever been formed by Europeans. We are very familiar with the African Egyptian hieroglyphic script and the African Ethiopian Geez script, which date as old as 3000 BC and 500 BC years respectively. However forgotten by no coincidence are many other ancient African scripts that are unique and expressive in their own ways. Scripts created and used for hundreds of years from Sudan to Nigeria. It appears that one of the main reasons why these great African script were lost in the sands of Historical time, is the direct mechanism of the colonial operation. Colonialism was internationally justified on a premise that the African was less than a human, this stamped by the infamous 1865 'Code Noir'. [2] To this goal, all evidence of African advanced skills would have been suppressed, books destroyed and higher skills silenced. -

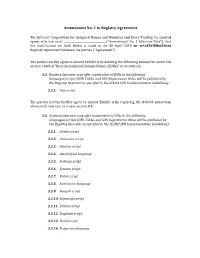

Amendment No. 1 to Registry Agreement

Amendment No. 1 to Registry Agreement The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and Kerry Trading Co. Limited agree, effective as of _______________________________ (“Amendment No. 1 Effective Date”), that the modification set forth below is made to the 30 April 2015 xn--w4r85el8fhu5dnra Registry Agreement between the parties (“Agreement”). The parties hereby agree to amend Exhibit A by deleting the following subsection under the section entitled “Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs)” in its entirety: 3.3. Registry Operator may offer registration of IDNs in the following languages/scripts (IDN Tables and IDN Registration Rules will be published by the Registry Operator as specified in the ICANN IDN Implementation Guidelines): 3.3.1. Han script The parties hereby further agree to amend Exhibit A by replacing the deleted subsection above with new text as a new section 3.3: 3.3. Registry Operator may offer registration of IDNs in the following languages/scripts (IDN Tables and IDN Registration Rules will be published by the Registry Operator as specified in the ICANN IDN Implementation Guidelines): 3.3.1. Arabic script 3.3.2. Armenian script 3.3.3. Avestan script 3.3.4. Azerbaijani language 3.3.5. Balinese script 3.3.6. Bamum script 3.3.7. Batak script 3.3.8. Belarusian language 3.3.9. Bengali script 3.3.10. Bopomofo script 3.3.11. Brahmi script 3.3.12. Buginese script 3.3.13. Buhid script 3.3.14. Bulgarian language 3.3.15. Canadian Aboriginal script 3.3.16. Carian script 3.3.17. Cham script 3.3.18.