Comparative Perspectives on the Study of Script Transfer, and the Origin of the Runic Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatolian Evidence Suggests That the Indo- European Laryngeals * H2 And

Indo-European Linguistics 6 (2018) 69–94 brill.com/ieul Anatolian evidence suggests that the Indo- European laryngeals *h2 and *h3 were uvular stops Alwin Kloekhorst Leiden University [email protected] Abstract In this article it will be argued that the Indo-European laryngeals *h2 and *h3, which recently have been identified as uvular fricatives, were in fact uvular stops in Proto- Indo-Anatolian. Also in the Proto-Anatolian and Proto-Luwic stages these sounds prob- ably were stops, not fricatives. Keywords Indo-European – laryngeals – phonological change – Indo-Anatolian 1 Background It is well-known that the Indo-European laryngeals *h2 and *h3 have in some environments survived in Hittite and Luwian as consonants that are spelled with the graphemes ḫ (in the cuneiform script) and h (in the hieroglyphic script).1 Although in handbooks it was usually stated that the exact phonetic interpretation of these graphemes is unclear,2 in recent years a consensus seems to have formed that they represent uvular fricatives (Kümmel 2007: 1 Although there is no full consensus on the question exactly in which environments *h2 and *h3 were retained as ḫ and h: especially the outcome of *h3 in Anatolian is debated (e.g. Kloekhorst 2006). Nevertheless, for the remainder of this article it is not crucial in which environments *h2 and *h3 yielded ḫ and h, only that they sometimes did. 2 E.g. Melchert 1994: 22; Hoffner & Melchert 2008: 38. © alwin kloekhorst, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22125892-00601003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC license at the time of publication. -

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

Herodotus' Conception of Foreign Languages

Histos () - HERODOTUS’ CONCEPTION OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES * Introduction In one of the most famous passages in his Histories , Herodotus has the Athe- nians give the reasons why they would never betray Greece (..): first and foremost, the images and temples of the gods, burnt and requiring vengeance, and then ‘the Greek thing’, being of the same blood and the same language, having common shrines and sacrifices and the same way of life. With race or blood, and with religious cult, language appears as one of the chief determinants of Greek identity. This impression is confirmed in Herodotus’ accounts of foreign peoples: language is—with religious customs, dress, hairstyles, sexual habits—one of the key items on Herodotus’ checklist of similarities and differences with foreign peoples. That language was an important element of what, to a Greek, it meant to be a Greek, should not perhaps be thought surprising. As is well known, the Greeks called non- Greeks βάρβαροι , a term usually taken to refer pejoratively to the babble of * This paper has been delivered in a number of different versions at St. Andrews, Newcastle, and at the Classical Association AGM. I should like to express my thanks to all those who took part in the subsequent discussions, and especially to Robert Fowler, Alan Griffiths, Robert Parker, Anna Morpurgo Davies and Stephanie West for their ex- tremely valuable comments on written drafts, to Hubert Petersmann for kindly sending me offprints of his publications, to Adrian Gratwick for his expert advice on a point of detail, and to David Colclough and Lucinda Platt for the repeated hospitality which al- lowed me to undertake the bulk of the research. -

Genetics of the Peloponnesean Populations and the Theory of Extinction of the Medieval Peloponnesean Greeks

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 637–645 Official journal of The European Society of Human Genetics www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks George Stamatoyannopoulos*,1, Aritra Bose2, Athanasios Teodosiadis3, Fotis Tsetsos2, Anna Plantinga4, Nikoletta Psatha5, Nikos Zogas6, Evangelia Yannaki6, Pierre Zalloua7, Kenneth K Kidd8, Brian L Browning4,9, John Stamatoyannopoulos3,10, Peristera Paschou11 and Petros Drineas2 Peloponnese has been one of the cradles of the Classical European civilization and an important contributor to the ancient European history. It has also been the subject of a controversy about the ancestry of its population. In a theory hotly debated by scholars for over 170 years, the German historian Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer proposed that the medieval Peloponneseans were totally extinguished by Slavic and Avar invaders and replaced by Slavic settlers during the 6th century CE. Here we use 2.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms to investigate the genetic structure of Peloponnesean populations in a sample of 241 individuals originating from all districts of the peninsula and to examine predictions of the theory of replacement of the medieval Peloponneseans by Slavs. We find considerable heterogeneity of Peloponnesean populations exemplified by genetically distinct subpopulations and by gene flow gradients within Peloponnese. By principal component analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE analysis the Peloponneseans are clearly distinguishable from the populations of the Slavic homeland and are very similar to Sicilians and Italians. Using a novel method of quantitative analysis of ADMIXTURE output we find that the Slavic ancestry of Peloponnesean subpopulations ranges from 0.2 to 14.4%. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

TOMASZ FRASZCZYK Greeklish – on the Influence of New

TOMASZ FRASZCZYK Greeklish – on the Influence of New Communication Technologies and New Media on the Development of Contemporary Greek KEY WORDS Greeklish, Greece, language, writing, media ABSTRACT The growing importance of English in the Western cultural circle is also an issue in the countries of the Mediterranean Sea. Research in the region shows that with the increasing popularity of electronic communication, especially with the use of SMS, the development of new media and the market offensive of social media like Facebook and Twitter, Greek is influenced not only by English, but also by Latinization, a process which has been termed Greeklish. The article presents a short history of Greek, as an introduction to its current development in the context of Greeklish. Its characteristics and origins in Greek writing are illustrated with the most representative examples from press, television and internet sites, along with typologies. The research outcome of documenting different aspects of using Greeklish have been discussed, as well as the most important issues in discussions taking place in Greece on possible consequences of this phenomenon on the development of Greek. The growing importance of English in countries of the Western culture is a phenomenon, which has also influenced the region of the Mediterranean Sea, among it Greece and Cyprus. The Anglicisation of the Greek language, but also of Polish, takes place by including English words in common, everyday use (e.g. weekend, lunch), structural borrowings1 or giving proper names in English (e.g. “Sea Towers” in Gdynia or “Wiśniowy Business Park” in Warsaw), and is only a certain element of the transformation process of contemporary Greek. -

ERILAZ a Ritual for Baritone, Violoncello and Percussion

Jeffrey Holmes ERILAZ a ritual for baritone, violoncello and percussion Score 2018 ce-jh1e1-dl-s JEFFREY HOLMES :ERILAZ: eRilay:ayt:alu A Ritual... for Baritone, Violoncello, and Percussion Text from the Lindholm amulet (DR 261, Rundata) ca. 3rd century, Skåne Full Score ii iii PERFORMANCE NOTES General 1. All tempi are approximate, but the relationships between tempi should be proportionally exact. 2. All accidentals apply through the measure and within one octave, and many cautionary accidentals are provided. 3. The following microtonal accidentals are used: B Quarter tone flat µ Quarter tone sharp J 1/6 tone lower than flat j 1/6 tone higher than flat K 1/6 tone lower than natural k 1/6 tone higher than natural L 1/6 tone lower than sharp l 1/6 tone higher than sharp 4. Pitches based on the harmonic series are labeled above the staff by their hypothetical fundamental and partial number. For example, G(7) indicates the seventh partial in the overtone series of G. (The fundamental is partial number 1.) These precise tunings are notationally approximated to the nearest quarter or sixth tone. Performers may either produce the notated quarter or sixth tone or, if accustomed to performing in just intonation, may produce the exact pitches of the indicated partials. Baritone In addition to singing, the baritone is asked to perform on three instruments: an Uruz horn (a primitive cowhorn) tuned to Eb, a lyre (or psaltery), and a drum, preferably a very large skinned tom-tom. Notation is as follows: iv Violoncello 1. The abbreviation s.t. -

Rethinking the Origins of the Greek Alphabet and Its Relation to the Other ‘Western’ Alphabets

This pdf of your paper in Understanding Relations Between Scripts II belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. This book is available open access and you may disseminate copies of your PDF as you wish. The book is available to download via the Open Access button on our website www.oxbowbooks.com. If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). - An open-access on-line version of this book is available at: http://books.casematepublishing.com/ Understanding_relations_between_Scripts_II_Early_alphabets. The online work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for copying any part of the online work for personal and commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Some rights reserved. No part of the print edition of the book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing. Materials provided by third parties remain the copyright of their owners. AN OFFPRINT FROM Understanding Relations Between Scripts II Early Alphabets Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-092-3 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-093-0 (ePub) edited by Philip J. Boyes and Philippa M. Steele Oxbow & Philadelphia Chapter 7 Mother or sister? Rethinking the origins of the Greek alphabet and its relation to the other ‘western’ alphabets Willemijn Waal According to prevailing opinion, the alphabet – the origins of which can be traced back to the beginning of the second millennium BC in Egypt – was introduced to Greece via the Phoenicians in or shortly before the eighth century BC. -

1 by Ellen Ndeshi Namhila 1. Africa Has a Rich and Unique Oral

THE AFRICAN PERPECTIVE: MEMORY OF THE WORLD By Ellen Ndeshi Namhila1 PREPARED FOR UNESCO MEMORY OF THE WORLD 3RD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA 19 TO 22 FEBRUARY 2008 1. INTRODUCTION Africa has a rich and unique oral, documentary, musical and artistic heritage to offer to the world, however, most of this heritage was burned down or captured during the wars of the scramble for Africa, and what had survived by accident was later intentionally destroyed or discontinued during the whole period of colonialism. In spite of this, the Memory of the World Register has so far enlisted 158 inscriptions from all over the world, out of which only 12 come from 8 African countries2. Hope was restored when on 30th January 2008, the Africa Regional Committee for Memory of the World was formed in Tshwane, South Africa. This paper will attempt to explore the reasons for the apathy from the African continent, within the framework of definitions and criteria for inscribing into the register. It will illustrate the breakdown and historical amnesia of memory and remembrance of the African heritage within the context of colonialism and its processes that have determined what was considered worth remembering as archives of enduring value, and what should be forgotten deliberately or accidentally. The paper argues that the independent African societies emerging from the colonial regimes have to make a conscious effort to revive their lost cultural values and identity. 2. A CASE STUDY: THE RECORDS OF BAMUM African had a rich heritage, well documented and well curated long before the Europeans came to colonise Africa. -

Anglo-Saxon Runes

Runes Each rune can mean something in divination (fortune telling) but they also act as a phonetic alphabet. This means that they can sound out words. When writing your name or whatever in runes, don’t pay attention to the letters we use, but rather the sounds we use to make up the words. Then finds the runes with the closest sounds and put them together. Anglo- Swedo- Roman Germanic Danish Saxon Norwegian A ansuz ac ar or god oak-tree (?) AE aesch ash-tree A/O or B berkanan bercon or birch-twig (?) C cen torch D dagaz day E ehwaz horse EA ear earth, grave(?) F fehu feoh fe fe money, cattle, money, money, money, wealth property property property gyfu / G gebo geofu gift gift (?) G gar spear H hagalaz hail hagol (?) I isa is iss ice ice ice Ï The sound of this character was something ihwaz / close to, but not exactly eihwaz like I or IE. yew-tree J jera year, fruitful part of the year K kenaz calc torch, flame (?) (?) K name unknown L laguz / laukaz water / fertility M mannaz man N naudiz need, necessity, nou (?) extremity ing NG ingwaz the god the god "Ing" "Ing" O othala- hereditary land, oethil possession OE P perth-(?) peorth meaning unclear (?) R raidho reth (?) riding, carriage S sowilo sun or sol (?) or sun tiwaz / teiwaz T the god Tiw (whose name survives in Tyr "Tuesday") TH thurisaz thorn thurs giant, monster (?) thorn giant, monster U uruz ur wild ox (?) wild ox W wunjo joy X Y yr bow (?) Z agiz(?) meaning unclear Now write your name: _________________________________________________________________ Rune table borrowed from: www.cratchit.org/dleigh/alpha/runes/runes.htm . -

Signs and Symbols Represented in Germanic, Particularly Early Scandinavian, Iconography Between the Migration Period and the End of the Viking Age

Signs and symbols represented in Germanic, particularly early Scandinavian, iconography between the Migration Period and the end of the Viking Age Peter R. Hupfauf Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney, 2003 Preface After the Middle Ages, artists in European cultures concentrated predominantly on real- istic interpretations of events and issues and on documentation of the world. From the Renaissance onwards, artists developed techniques of illusion (e.g. perspective) and high levels of sophistication to embed messages within decorative elaborations. This develop- ment reached its peak in nineteenth century Classicism and Realism. A Fine Art interest in ‘Nordic Antiquity’, which emerged during the Romantic movement, was usually expressed in a Renaissance manner, representing heroic attitudes by copying Classical Antiquity. A group of nineteenth-century artists, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Everett Millais founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. John Ruskin, who taught aesthetic theory at Oxford, became an associate and public defender of the group. The members of this group appreciated the symbolism and iconography of the Gothic period. Rossetti worked together with Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. Morris was a great admirer of early Scandinavian cultures, and his ideas were extremely influential for the development of the English Craft Movement, which originated from Pre-Raphaelite ideology. Abstraction, which developed during the early twentieth century, attempted to communicate more directly with emotion rather then with the intellect. Many of the early abstract artists (Picasso is probably the best known) found inspiration in tribal artefacts. However, according to Rubin (1984), some nineteenth-century primitivist painters appreciated pre-Renaissance European styles for their simplicity and sincerity – they saw value in the absence of complex devices of illusio-nist lighting and perspective. -

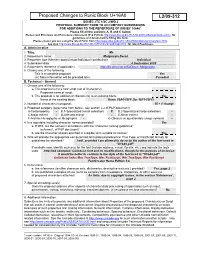

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4.