The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Issn 2654-1823

SAFEGREECE CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS ISSN 2654-1823 14-17.10 proceedings SafeGreece 2020 – 7th International Conference on Civil Protection & New Technologies 14‐16 October, on‐line | www.safegreece.gr/safegreece2020 | [email protected] Publisher: SafeGreece [www.safegreece.org] Editing, paging: Katerina – Navsika Katsetsiadou Title: SafeGreece 2020 on‐line Proceedings Copyright © 2020 SafeGreece SafeGreece Proceedings ISSN 2654‐1823 SafeGreece 2020 on-line Proceedings | ISSN 2654-1823 index About 1 Committees 2 Topics 5 Thanks to 6 Agenda 7 Extended Abstracts (Oral Presentations) 21 New Challenges for Multi – Hazard Emergency Management in the COVID-19 Era in Greece Evi Georgiadou, Hellenic Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (ELINYAE) 23 An Innovative Emergency Medical Regulation Model in Natural and Manmade Disasters Chih-Long Pan, National Yunlin University of Science and technology, Taiwan 27 Fragility Analysis of Bridges in a Multiple Hazard Environment Sotiria Stefanidou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 31 Nature-Based Solutions: an Innovative (Though Not New) Approach to Deal with Immense Societal Challenges Thanos Giannakakis, WWF Hellas 35 Coastal Inundation due to Storm Surges on a Mediterranean Deltaic Area under the Effects of Climate Change Yannis Krestenitis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 39 Optimization Model of the Mountainous Forest Areas Opening up in Order to Prevent and Suppress Potential Forest Fires Georgios Tasionas, Democritus University of Thrace 43 We and the lightning Konstantinos Kokolakis, -

MODULA-2 TRANSLATOR USER's MANUAL First Edition May 1986

LOGITECH SOFTWARE ENGINEERING LIBRARY PASCAL TO MODULA-2 TRANSLATOR USER'S MANUAL First Edition May 1986 Copyright (C) 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987 LOGITECH, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No part of this document may be copied or reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of LOGITECH, Inc. LOGITECH, MODULA-2186,and MODULA-2IVX86 are trademarks ofLOGITECH, Inc. Microsoft is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation. MS-DOS is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Intel is a registered trademark ofIntel Corporation. IBM is a registered trademark ofInternational Business Machines Corporation. Turbo Pascal is a registered trademark ofBorland International, Inc. LOGITECH, Inc. makes no warranties with respect to this documentation and disclaims any implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. The information in this document is subject to change without notice. LOGITECH, Inc. assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this document. From time to time changes may occur in the filenames and in the files actually included on the distribution disks. LOGITECH, Inc. makes no warranties that such files or facilities as mentioned in this documentation exist on the distribution disks or as part of the materials distributed. LU-GUllO-1 Initial issue: May 1986 Reprinted: September 1987 This edition applies to Release 1.00 or later of the software. ii TRANSLATOR Preface LOGITECH'S POLICIES AND SERVICES Congratulations on the purchase of your LOGITECH Pascal To Modula-2 Translator. Please refer to the following infonnation for details about LOGITECH's policies and services. We feel that effective communication with our customers is the key to quality service. -

Owner's Manual Hercules Graphics Card (GB101)

• f I • I '! ( w ....,(]) (]) Contents b/J;>, ....,o.l ....,o.l :...o.l ""(]) W. ~~~Q)~ il<~:s~,~o (]) .::: zz::::.:io 1 Getting Started What is the Hercules Graphics Card? 1 Inventory Checklist 1 How to install the Graphics Card 2 The Graphics Card's "Software Switch" 3 HBASIC 5 2 For Advanced Users Configuring the Graphics Card 8 ~ bJj Programming 9 ~ 0 U 1"""""4 Interfacing the Graphics Card 9 ><- 0 Display Interface 9 ~ ...:l s::: ~ ...c: Printer Interface 13 ~ ~ ~ Generating Text 15 ~ 1"""""4 ~ ~ Generating Graphics 16 ........ ~ ro C\l <l.) 0 (]) C\l (]) ...j..J 00 w A Appendix ~ w (]) ~ ~ o :... Z ~ ']}oubleshooting 17 I"""""4 "" 1 ~ t: ""~ S <l.) ::S ;>, 2 Register Descriptions Table 18 ~ 0 ~ fj 0 3 Application Notes 19 il< '@ ""il< W. W. 4 Modifying the Diagnostics Program 22 (]) <l.) ...., ,....0 W. w. ~ (]) w. 1"""""4 (]) t- <l.) :... ~ ~ ...., Ol Index 23 ...:l w. "'"o.l . .......s::: U ti ~ ;>, (]) ..s::...., (]) '2 W. E-< b/J ~ Q) :... W. o.l <l.) Ol ...., 0 ..>:: ~ ~ w I.Q :... ~ ...... 0 I.Q (]) "'@ ~ r:... il< ~ C\l ~ U 1 Getting Started What is the Hercules Graphics Card? The Hercules Graphics Card is a high resolution graphics card for the IBM PC monochrome display. It replaces the IBM monochrome display/printer adapter and is compatible with its software. The Graphics Card uses the same style high resolution monochrome character set and comes with a parallel printer interface. The Hercules Graphics Card offers two graphics pages each with aresolution of 720h x 348v. Software supplied with the Graphics Card allows the use of the BASIC graphics commands. -

E-Academy Course List

CourseID Course Code Course Name Course Description Credit Hours 283222 REL-HHS-0-NCV2 10 Steps to Fully Integrating Peers The results are in and it is clear that peers improve opportunities and 1 into your Workforce outcomes for the people we serve. At the same time many organizations struggle to successfully create opportunities for this workforce. This workshop will explore the top ten strategies for success at incorporating the peer workforce and the critical role that organizational culture plays in this transformation of care. 302177 REL-ALL-0- 2010 MS Excel: Advanced This advanced course on Microsoft Excel 2010 covers creating and 0 EXCEL10ADV running macros. 302175 REL-ALL-0- 2010 MS Excel: Basics This course will teach you the basics of Microsoft Excel 2010 0 EXCEL10BAS including creating a chart, keyboard shortcuts, protecting your files, and more. 302176 REL-ALL-0- 2010 MS Excel: Intermediate This intermediate level course on Microsoft Excel 2010 will cover 0 EXCEL10INT formulas and functions, conditional formatting, Vlookup, keyboard shortcuts, and more. 302186 REL-ALL-0- 2010 MS Outlook: Basics This course will teach you the basics of Microsoft Outlook 2010 0 OUTLK10BAS including mailbox management, signatures, automatic replies, and more. 302187 REL-ALL-0- 2010 MS Outlook: Intermediate This intermediate level course on Microsoft Outlook 2010 covers 0 OUTLK10INT keyboard shortcuts, best practices, and more. 302181 REL-ALL-0-PPT10BAS 2010 MS PowerPoint: Basics This course will teach you the basics of Microsoft PowerPoint 2010 0 including charts and diagrams, keyboard shortcuts, animations and transitions, inserting videos, and more. 302182 REL-ALL-0-PPT10INT 2010 MS PowerPoint: Intermediate This intermediate level course on Microsoft PowerPoint 2010 will 0 provide an indepth coverage of using animations. -

Rapid Application Development Resumo Abstract

Rapid Application Development Otavio Rodolfo Piske – [email protected] Fábio André Seidel – [email protected] Especialização em Software Livre Centro Universitário Positivo - UnicenP Resumo O RAD é uma metodologia de desenvolvimento de grande sucesso em ambientes proprietários. Embora as ferramentas RAD livres ainda sejam desconhecidas por grande parte dos desenvolvedores, a sua utilização está ganhando força pela comunidade de software livre. A quantidade de ferramentas livres disponíveis para o desenvolvimento RAD aumentou nos últimos anos e mesmo assim uma parcela dos desenvolvedores tem se mostrado cética em relação a maturidade e funcionalidades disponíveis nestas ferramentas devido ao fato de elas não estarem presentes, por padrão, na maioria das distribuições mais utilizadas. Além disso, elas não contam com o suporte de nenhum grande distribuidor e, ainda que sejam bem suportadas pela comunidade, este acaba sendo um empecilho para alguns desenvolvedores. Outro foco para se utilizar no desenvolvimento RAD é a utilização de frameworks, onde esses estão disponíveis para desenvolvimento em linguagens como C e C++ sendo as mais utilizadas em ambientes baseados em software livre, embora estas linguagens não sejam tão produtivas para o desenvolvimento de aplicações rápidas. Abstract RAD is a highly successful software development methodology in proprietary environments. Though free RAD tools is yet unknown for a great range of developers, its usage is growing in the free software community. The amount of free RAD tools available has increased in the last years, yet a considerable amount of developers is skeptic about the maturity and features available in these tools due to the fact that they are not available by default on the biggest distribution. -

BASIC Programming with Unix Introduction

LinuxFocus article number 277 http://linuxfocus.org BASIC programming with Unix by John Perr <johnperr(at)Linuxfocus.org> Abstract: About the author: Developing with Linux or another Unix system in BASIC ? Why not ? Linux user since 1994, he is Various free solutions allows us to use the BASIC language to develop one of the French editors of interpreted or compiled applications. LinuxFocus. _________________ _________________ _________________ Translated to English by: Georges Tarbouriech <gt(at)Linuxfocus.org> Introduction Even if it appeared later than other languages on the computing scene, BASIC quickly became widespread on many non Unix systems as a replacement for the scripting languages natively found on Unix. This is probably the main reason why this language is rarely used by Unix people. Unix had a more powerful scripting language from the first day on. Like other scripting languages, BASIC is mostly an interpreted one and uses a rather simple syntax, without data types, apart from a distinction between strings and numbers. Historically, the name of the language comes from its simplicity and from the fact it allows to easily teach programming to students. Unfortunately, the lack of standardization lead to many different versions mostly incompatible with each other. We can even say there are as many versions as interpreters what makes BASIC hardly portable. Despite these drawbacks and many others that the "true programmers" will remind us, BASIC stays an option to be taken into account to quickly develop small programs. This has been especially true for many years because of the Integrated Development Environment found in Windows versions allowing graphical interface design in a few mouse clicks. -

An Inventory of Irrigation Software for Microcomputers

AN INVENTORY OF IRRIGATION SOFTWARE FOR MICROCOMPUTERS K.J. Lenselink & M. Jurriëns Wageningen, January 1993 International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement/ ILRI, Wageningen, The Netherlands I TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 References 3 2. COMPUTER USE; TRENDS, TYPES AND LIMITATIONS 2.1 General trends 5 2.2 Types and purposes of computer use 6 2.3 Computer use in irrigation 7 2.4 Limitations 9 References 10 3. ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY 3.1 Set-up and execution 11 3.2 Structure of the report 11 3.3 Loose ends 13 References 14 4. IRRIGATION GAMES 4.1 Background information 15 4.2 Non-computer based games 16 4.3 Computer-based games 19 References 23 5. WATER REQUIREMENTS AND SCHEDULING 5.1 Crop water requirements 25 5.2 Programs for water requirements 26 5.3 Irrigation scheduling 28 5.4 Irrigation scheduling programs 30 References 31 6. FIELD IRRIGATION 6.1 Surface irrigation 35 6.2 Surface irrigation programs 37 6.3 Pressurized irrigation programs 41 6.4 Other programs 42 References 43 7. CANALS AND CANAL NETWORKS 7.1 Open channels 47 7.2 Types of programs 48 7.3 Programs for channel design 49 7.4 Programs for open distribution networks 52 References 55 8. PIPE NETWORKS 8.1 Pipe flow 59 8.2 Pipe networks 60 8.3 Programs for network calculations 61 References 62 9. STRUCTURES 9.1 Irrigation structures 65 9.2 Programs for weir design 66 References 68 10. IRRIGATION SYSTEM MANAGEMENT 10.1 Defining the subject 71 10.2 Types of programs 72 10.3 Programs for irrigation system management 73 10.4 Other programs 76 References 78 11. -

Deep Scrutiny of Compilers in Industry with Estimating on Conglomerate Factors

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 11, 2020 Deep scrutiny of compilers in industry with estimating on conglomerate factors Dr Sandeep Kulkarni 1, Prof(Dr) K P Yadav 2 1,2Sangum University, Bilwara, Rajasthan [email protected], [email protected] Received: 05 May 2020 Revised: and Accepted: 15 July 2020 ABSTRACT: As to understand the basic knowledge of compilers , various types of compilers in the programming world ,we will study in detail the compilers available in various languages. As we are going to study their compilers working usage for which they have used in various companies in software industries. M- DOS with Microsoft windows uses Borland C++ compilers with the help of any C and C++Integrated development environment tool. As it is advance version when compared to Turbo C++ it known for good performance in debugging purpose so for this Turbo debugger and this software is written mode of DOS which is protected.There are set of library which is helpful for building graphical windows projects known as Object windows library . With the C++ program DOS applications is created. Applications such as pop up boxes, application top menus, dialog boxes for this turbo vision is used. Applications presenting in 2 dimensional drawing. Borland graphics libraries CGA and VGA , it also supports third party supporting classes and also video libraries. Industries supporting or developing these kind of applications are GSN Consulting, Einfochips Limited. So will have detailed study on programming language used in industry on compiler based performances. KEYWORDS: Deep scrutiny of compilers in industry with estimating on conglomerate factors I. -

CODAR: a Contextual Duration-Aware Qubit Mapping for Various NISQ Devices

CODAR: A Contextual Duration-Aware Qubit Mapping for Various NISQ Devices Haowei Deng, Yu Zhang∗ and Quanxi Li School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China Email: [email protected], [email protected]∗, [email protected] Abstract—Quantum computing devices in the NISQ era share In this paper, we focus on solving the qubit mapping problem by common features and challenges like limited connectivity between heuristic search with the consideration of gate duration difference qubits. Since two-qubit gates are allowed on limited qubit pairs, and program context to explore more program’s parallelism. To quantum compilers must transform original quantum programs address the challenges of qubit mapping problem and adapt to to fit the hardware constraints. Previous works on qubit mapping different quantum technologies, we first give several examples to assume different gates have the same execution duration, which explain our motivation, then propose a Multi-architecture Adaptive limits them to explore the parallelism from the program. To Quantum Abstract Machine (maQAM) for studying the qubit map- address this drawback, we propose a Multi-architecture Adaptive ping problem. The maQAM is modeled as a coupling graph with Quantum Abstract Machine (maQAM) and a COntext-sensitive limited qubit connectivity and configurable durations of different and Duration-Aware Remapping algorithm (CODAR). The CO- kinds of quantum gates. Based on the maQAM, we further propose DAR remapper is aware of gate duration difference and program two mechanisms that enable COntext-sensitive and Duration-Aware context, enabling it to extract more parallelism from programs Remapping algorithm (CODAR) to solve the qubit mapping problem and speed up the quantum programs by 1.23 in simulation on with the awareness of gate duration difference and program context. -

MEMORANDUM Council and Executive Community Grants

AGENDA ITEM May 15,2012 Worksession MEMORANDUM May 11,2012 TO: County Council f; FROM: Peggy FitZgerald-BEtCouncil Grants Manager SUBJECT: Council and Executive Community Grants Those expected to attend this worksession include: Beryl L. Feinberg, Office ofManagement and Budget On May 15, the Council is scheduled to act on the County Executive's recommended Community (discretionary) Grants, and Council Grants. The Executive's 102 recommended Community Grants totaling $3,719,570 are listed on ©1-3. The Staff List of 39 recommended grants, totaling $1,349,780 is listed on ©IS-16. The Council President intends to recommend additional Council Grants. They will be distributed via an Addendum to this packet prior to the Council worksession. The Community Grants, except where noted, are considered directly by the County Council and so there is no Committee recommendation. Council Grants Manager recommends that the Council take the following actions today: • Approve County Executive recommended Community Grants; • Place Staff List of recommended Council Grants on the Reconciliation List; • Place Council President List of additional recommended Council Grants on the Reconciliation List; • Approve Budget Resolution language listed on pages 2-3. Background On October 25,2011, the Montgomery County Council adopted Resolution #17 288 which established an application and review process for funding requests from non profit agencies for FY13. In addition, for FY13 the Council indicated that it "is particularly interested in proposals that provide emergency and other assistance to the neediest members of our community." The FY13 Council Grant Application and supporting materials noted this Council priority for FYI3. On February 14,2012, as part ofthe Council's actions on Spending Affordability Guidelines for the FY13 Operating Budget, the Council set an overall target spending allocation for Council grants of $2.2 million and another $2.2 million for Executive recommended Community Grants. -

Porting Visual Basic Apps to Linux OPENING DOORS Realbasic Provides an Easy Solution for Convert- Ing Visual Basic Programs to Linux

COVER STORY Realbasic Porting Visual Basic apps to Linux OPENING DOORS Realbasic provides an easy solution for convert- www.sxc.hu ing Visual Basic programs to Linux. BY FRANK WIEDUWILT isual Basic owes its popularity in and enhancements for a fixed period of the world of Windows to its rep- time. After this time, the customer re- Vutation as an easy-to-learn and tains the license but does not get the easily readable programming language. bugfixes. Real Software promises to re- But users moving to Linux typically have lease a new version every 90 days, so li- to re-write their Visual Basic programs in censed users can look forward to new a different language. Free Basic variants features at regular intervals. such as Gambas [1], HBasic [2], or WX- The Standard Edition for Linux is free; Basic [3] are just too far removed from the Professional Version costs 330 Euros VB to support no-worries porting. KBasic (US$ 399.95) with six months worth of [4] promises complete syntactical com- updates. Other license arrangements are patibility to Visual Basic, but it is still at also available. Table 1 shows the differ- a fairly unstable beta stage despite sev- ences between the two versions. eral years of development. Real Software The Professional version of Realbasic Figure 2: A cross hair cursor facilitates recently launched Realbasic [5], a com- for Linux can create programs for any accurate positioning of GUI elements. mercial tool designed to pick up Visual Windows version from 95 through to XP. Basic projects and give users the ability The programs do not require any addi- documentation is also available from the to run them on Linux and Mac OS X. -

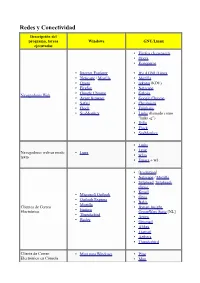

Redes Y Conectividad Descripción Del Programa, Tareas Windows GNU/Linux Ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror

Redes y Conectividad Descripción del programa, tareas Windows GNU/Linux ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror • Internet Explorer • IEs 4 GNU/Linux • Netscape / Mozilla • Mozilla • Opera • rekonq (KDE) • Firefox • Netscape • Google Chrome • Galeón Navegadores Web • Avant Browser • Google Chrome • Safari • Chromium • Flock • Epiphany • SeaMonkey • Links (llamado como "links -g") • Dillo • Flock • SeaMonkey • Links • • Lynx Navegadores web en modo Lynx • texto w3m • Emacs + w3. • [Evolution] • Netscape / Mozilla • Sylpheed , Sylpheed- claws. • Kmail • Microsoft Outlook • Gnus • Outlook Express • Balsa • Mozilla Clientes de Correo • Bynari Insight • Eudora Electrónico GroupWare Suite [NL] • Thunderbird • Arrow • Becky • Gnumail • Althea • Liamail • Aethera • Thunderbird Cliente de Correo • Mutt para Windows • Pine Electrónico en Cónsola • Mutt • Gnus • de , Pine para Windows • Elm. • Xemacs • Liferea • Knode. • Pan • Xnews , Outlook, • NewsReader Lector de noticias Netscape / Mozilla • Netscape / Mozilla. • Sylpheed / Sylpheed- claws • MultiGet • Orbit Downloader • Downloader para X. • MetaProducts Download • Caitoo (former Kget). Express • Prozilla . • Flashget • wxDownloadFast . • Go!zilla • Kget (KDE). Gestor de Descargas • Reget • Wget (console, standard). • Getright GUI: Kmago, QTget, • Wget para Windows Xget, ... • Download Accelerator Plus • Aria. • Axel. • Httrack. • WWW Offline Explorer. • Wget (consola, estándar). GUI: Kmago, QTget, Extractor de Sitios Web Teleport Pro, Webripper. Xget, ... • Downloader para X. •