GEOGRAPHY Dr. N. M. Kadam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-175649-10.Pdf

1: '*"'" GOVERNMENT OF MAIIAitASJRllA OUTLINE· OF · ACTIVITIES For 1977-78 and 1978-79 IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT OUTLINE OF ACTIVITIES 1977-78 AND 1978-79 IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT CONTENTS CHAl'TI!R PAGtiS I. Introduction II. Details of Major and Medium Irrigation Projects 6 Ul. Minor Irrigation Works (State sector) and Lift Irrigation 21 IV. Steps taken to accelerate the pace of Irrigation Development 23 V. Training programme for various Technical and Non-Technical co~ 36 VI. Irrigation Management, Flood Control and ElCiension and Improvement 38 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I.· The earstwhile Public Works Department was continued uuaffect~u after Independence in 1947, but on formation of the State ot Maharashtra in 1_960, was divided into two Departments. viz. .(1) Buildings and Communica· ticns Dep4rtment (now named · as ·'Public Works ' and Housing Department) and (ii) Irrigation and Power Department, as it became evident that the Irrigation programme to be t;~ken up would ·need a separate Depart· ment The activities in . both the above Departments have considerably increased since then and have nei:eSllitated expansion of both the Depart ments. Further due t~ increased ·activities of the Irrigation and Power Department the subject <of Power (Hydro only) has since been allotted to Industries,"Energy and· Labour Department. Public Health Engineering wing is transferred to Urban. Development and Public Health Department. ,t2.. The activities o(the Irrigation ·Department can be divided broadly into the following categories :- (i) Major and Medium Irrigation Projects. (u) Minor Irrigation Projects (State Sector). (ii1) Irrigation Management. (iv) Flood Control. tv) Research. .Designs and Training. (vi) Command Area Development. (vii) Lift Irrigation Sc. -

Bpc(Maharashtra) (Times of India).Xlsx

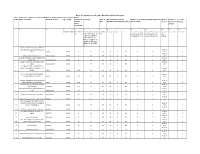

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships BPCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra as per following details : Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be arranged by the applicant Mode of Fixed Fee / Security monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). * (Rs in Lakhs) Selection Minimum Bid Deposit Sales amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / Rural MS+HSD in SC/ SC CC1/ SC CC- CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area Estimated working Estimated fund required Draw of Rs in Lakhs Rs in Lakhs Kls 2/ SC PH/ ST/ ST CC- FS capital requirement for development of Lots / 1/ ST CC-2/ ST PH/ for operation of RO infrastructure at RO Bidding OBC/ OBC CC-1/ OBC CC-2/ OBC PH/ OPEN/ OPEN CC-1/ OPEN CC-2/ OPEN PH From Aastha Hospital to Jalna APMC on New Mondha road, within Municipal Draw of 1 Limits JALNA RURAL 33 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 VIllage jamgaon taluka parner AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE KOMBHALI,TALUKA KARJAT(NOT Draw of 3 ON NH/SH) AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Ambhai, Tal - Sillod Other than Draw of 4 NH/SH AURANGABAD RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON MAHALUNGE - NANDE ROAD, MAHALUNGE GRAM PANCHYAT, TAL: Draw of 5 MULSHI PUNE RURAL 300 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON 1.1 NEW DP ROAD (30 M WIDE), Draw of 6 VILLAGE: DEHU, TAL: HAVELI PUNE RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE- RAJEGAON, TALUKA: DAUND Draw of 7 ON BHIGWAN-MALTHAN -

Chapter 7 Problems of Agriculture and Agro

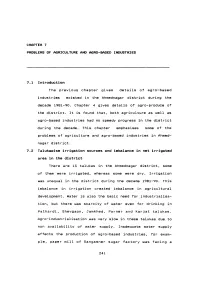

CHAPTER 7 PROBLEMS OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRIES 7.1 Introduction The previous chapter gives details of agro-based industries existed in the Ahmednagar district during the decade 1981-90. Chapter 4 gives d e ta ils of agro-produce of the d is t r ic t . I t is found that, both ag ric u ltu re as well as agro-based industries had no speedy progress in the district during the decade. This chapter emphasises some of the problems of a g ric u ltu re and agro-based industries in Ahmed nagar d is t r ic t . 7.2 TalukaMise irrigation sources and imbalance in net irrigated area in the district There are 13 talukas in the Ahmednagar district, some of them were irrig a te d , whereas some were dry. Ir r ig a tio n was unequal in the d is t r ic t during the decade 1981-90. This imbalance in irrigation created imbalance in agricultural development. Water is also the basic need for industrialisa tion, but there was scarcity of water even for drinking in Pathardi, Shevgaon, Jamkhed, Parner and Karjat talukas. Agro-industrialisation was very slow in these talukas due to non availability of water supply. Inadequate water supply affects the production of agro-based industries, for exam ple, paper mill of Sangamner sugar factory was facing a 241 severe problem of water supply during the year 1986-87, which affected the production of th is m ill.^ There are two types of irrigation. One is well irriga tion and the other is surface irrigation. -

Records of Freshwater Bryozoa in Mula Dam of Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra, India

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2014; 2 (6): 99-101 ISSN 2320-7078 Records of freshwater Bryozoa in Mula Dam of JEZS 2014; 2 (6): 99-101 © 2014 JEZS Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra, India. Received: 27-10-2014 Accepted: 16-11-2014 Pavan S. Swami, Satish S. Mokashe and Ananta D. Harkal Pavan S. Swami Abstract Department Of Zoology, Dr. The Bryozoa are also known as polyzoa, ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals. Bryozoans are Babasaheb Ambedkar important in water quality monitoring and palaeolimnological research and for controlling their growth as Marathwada University, fowlers. Present paper reports for the first time the occurrence of two bryozoan species namely. Aurangabad 431004 (M.S) India. Asajirella gelatinosa and Lophopodella carteri in Mula dam, Ahmednagar. The species were identified by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images of Statoblasts (encapsulated bud produced asexually by Satish S. Mokashe bryozoans) and colony morphology. Study on diversity of fresh water bryozoans may help to understand Department Of Zoology, Dr. its role in food chain of freshwater ecosystem. Babasaheb Ambedkar Keywords: Asajirella gelatinosa, Freshwater Bryozoa, Lophopodella carteri, Mula dam, SEM. Marathwada University, Aurangabad 431004, (M.S) India. 1. Introduction [1] Freshwater bryozoans are aquatic invertebrate animals , they are filter feeders and draw tiny Ananta D. Harkal food particle towards the mouth by means of ciliated tentacles. Although bryozoans are widely New Arts, Commerce and Science distributed in epibenthic and littoral communities little is known about their zoogeographical College, Ahmednagar-414001 status. Moreover, at the species level freshwater bryozoan are quite difficult to identify (M.S) India. because of their high morphological variability. -

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT for AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT PART -A

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT For AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT PART -A FOR SAND MINING OR RIVER BED MINING 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1. LOCATION & GEOGRAPHICAL DATA: Ahmednagar is the largest district of Maharashtra State in respect of area, popularly known as “Nagar”. It is situated in the central part of the State in upper Godavari basin and partly in the Bhima basin and lies between north latitudes 18°19’ and 19°59’ and east longitudes 73°37’ and 75°32’ and falls in parts of Survey of India degree sheets 47 E, 47 I, 47 M, 47 J and 47 N. It is bounded by Nashik district in the north, Aurangabad and Beed districts to the east, Osmanabad and Solapur districts to the south and Pune and Thane districts to the west. The district has a geographical area of 17114 sq. km., which is 5.54% of the total State area. The district is well connected with capital City Mumbai & major cities in Maharashtra by Road and Railway. As per the land use details (2011), the district has an area of 134 sq. km. occupied by forest. The gross cultivable area of district is 15097 sq.km,whereas net area sown is 11463 sq.km. Figure 1 :Ahmednagar District Location Map 2 Table 1.1 – Geographical Data SSNo Geographical Data Unit Statistics . 18°19’ N and 19°59’N 1. Latitude and Longitude Degree To 73°37’E and 75°32’E 2. Geographical Area Sq. Km 17114 1.2. ADMINISTRATIVE SET UP: It is divided in to 14 talukas namely Ahmednagar, Rahuri, Shrirampur, Nevasa, Shevgaon, Pathardi, Jamkhed, Karjat, Srigonda, Parner, Akole, Sangamner, Kopargaon and Rahata. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

Chapter 4 Sole of Sugar Cooperatives In

CHAPTER 4 SOLE OF SUGAR COOPERATIVES IN DEVELOPMENT OF IRRIGATION FACILITIES 4.1 Introdwctj-Qft As seen in the previous chapter, the problem of distribution of water between sugarcane cultivating areas and other areas has been an important issue since the beginning of the 20th century. Now, as I have examined the issue only at the macro level in the previous chapter, it is necessary to see how some individual cooperative sugar factories have really acted in the area of irrigation development and how their activities affected other areas than their command areas or other parties than sugarcane-growers. In this chapter, at first, efforts on irrigation development of a few sugar cooperatives are examined, and then, the effects of irrigation development by sugar cooperatives on other areas or other parties are studied with examples from a few districts in Maharashtra. 4.2 Vasantdada Shetkari SuRag C<?PPei:9tiYfi> The case of Vasantdada Shetkari Sahakari Sakhar Karkhana Ltd., Sangli is worth noting because, although Sangli was not a traditionally known sugarcane-cultivating area, amazingly rapid development of lift irrigation was seen fcr in the early history of this sugar cooperative, because of the foresight and help of a notable leader, Vasantdada Patil. When the factory started its first crushing season in 1958, the area under sugarcane available to it from its command area was not more than 800 hectares. In the command area of the factory, there were 3 rivers flowing, namely, the Krishna, the Warna and the Verla; however, the government was then thinking that lift irrigation projects on rivers were not feasible. -

Chapter II GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND of SHRIGONDA TAHSIL

Chapter II GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF SHRIGONDA TAHSIL CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF SHRIGONDA TAHSIL 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Location 2.3 Physiography and Drainage 2.4 Geology 2.5 Soils 2.6 Climate 2.6.1 Rainfall 2.7 Natural Vegetation 2.8 Irrigation 2.9 Total Population and Density of Population 2.10 Sex Ratio 2.11 Literacy Ratio 2.12 Transportation 2.13 Weekly Market Centers 2.14 Land Utilization 2.15 Agriculture Landuse Pattern 20 CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF SHRIGONDA TAHSIL 2.1 Introduction Shrigonda tahsil, the study area, is the third largest tahsil in Ahmednagar district. It was a part and parcel of the Maratha and Peshvaj region, which had distinctive geographical personality. Shrigonda tahsil is located in southern drought prone zone of Ahmednagar district. It is situated partly in upper Saraswati basin a tributary of river Bhima and partly river Bhima and river Ghod another tributary of river Bhima. The length of the tahsil is 60 Km. from East to West and the width is 51 Km. from North to south. The average height of tahsil is 600 mt. (as per the toposheet) above the mean sea level. Generally slope of tahsil is from north to south. The water divide running from east to west is locally known as “Khkiba Donger”. Geographical area is about 1629.94 Km2 and it occupies 9.56 percent of the total area of the district. The total population of the Shrigonda tahsil is 315975 (as per the census of 2011). 2.2 Location Study area is located in the southern drought prone zone of Ahmednagar district. -

GIS and RS BASED PHYSIOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS of SOUTH AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT Dr

Mukt Shabd Journal Issn No : 2347-3150 GIS AND RS BASED PHYSIOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF SOUTH AHMEDNAGAR DISTRICT Dr. Santosh J. Lagad Department of Geography, Dada Patil Mahavidyalaya, Karjat. Dist.-Ahmednagar, 414402 Maharashtra (India). Email – [email protected] ABSTRACT Geographical Information System (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) Techniques provides reliable and accurate information of the regions. These techniques are found relevant and rationalize information of the morphology, relief, elevation, slop, drainage patterns etc. features of the region. South Ahmednagar District is situated on decan trap and it is drought prone district. This district has immense variety in physical aspects. Especially south part of district has undulating topography and this types of topography directly and indirectly affects physical and cultural environment of the study area. The aim of present paper is to acknowledge the physiographic of South Ahmednagar District through GIS and RS techniques. Key Words: Drought, GIS, Morphology, RS, Topography INTRODUCTION Physiographic of any region plays important role for the development of a region. Physical aspects are the mirror of socio-economic development of the region. All these abiotic aspect like as morphology, relief, slope, drainage, soil etc. together are the geo-wealth of region ( Kale V.S. 2015).Variation of these aspects are directly affects socio-economic condition of the region. The socio-economic condition and its interaction within itself play an important role. That is why it becomes necessary to study how these factors exert their influence. Physical factors do play a vital role in the economic development of the region. The natural resources like relief, drainage, soil, water, forest and climate contribute to the economic development of the region. -

1 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33KV Kedgaon 10.00 2 Ahmednagar PARNER PALASPUR 5.00 3 Ahmednagar PARNER BHALWANI 4.00 4 Ahmednagar PARN

ADDENDUM-1 T-08 (Ahmednagar) Tentative list of MSEDCL sub-stations for grid connectivity at 22 or 11KV Level of proposed 2 to 10 MW Solar generation projects to be developed under this tender Capacity Available in MW for Sr.No. Name of Circle Name of Taluka Name of S/s Solar Project 1 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33KV Kedgaon 10.00 2 Ahmednagar PARNER PALASPUR 5.00 3 Ahmednagar PARNER BHALWANI 4.00 4 Ahmednagar PARNER GOREGAON 5.00 5 Ahmednagar PARNER DHWALPURI 5.00 6 Ahmednagar PARNER SUPA MIDC 15.00 7 Ahmednagar PARNER SUPA OLD 10.00 8 Ahmednagar PARNER PIMPLIGAWLI 5.00 9 Ahmednagar PARNER NARAYAN GWHAN 13.00 10 Ahmednagar PARNER RALEGANTHERPAL 10.00 11 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33/11 KV CHICHONDI PATIL 8.00 12 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33/11 KV MEHEKARI 13.00 13 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33/11 KV DEHARE S/STN 10.00 14 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar Mula Dam 8.00 15 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar Hiware Bazar 10.00 16 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar NARAYAN DOH 5.00 17 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar 33/11 KV GUNDEGAON 5.00 18 Ahmednagar NEWASA BELPIMPALGAON 5.00 19 Ahmednagar NEWASA BHANASHIVARA 15.00 20 Ahmednagar NEWASA GEVRAI 10.00 21 Ahmednagar NEWASA BHENDA 20.00 22 Ahmednagar NEWASA U.KHALSA 10.00 23 Ahmednagar NEWASA KARAJGAON 15.00 24 Ahmednagar NEWASA KHADKA 15.00 25 Ahmednagar NEWASA KHAMGAON 10.00 26 Ahmednagar NEWASA SALABATPUR 20.00 27 Ahmednagar NEWASA SHIRASGAON 20.00 28 Ahmednagar Nweasa 33/11 KV Chanda 10.00 29 Ahmednagar Nweasa 33/11 KV Maka 5.00 30 Ahmednagar Nweasa 33/11 KV Sonai 20.00 31 Ahmednagar Nweasa 33/11 KV Shingnapur 20.00 32 Ahmednagar Nweasa 33/11 KV Deogaon -

Hamilton) in Dyneshawar Sagar Mulanagar, Rahuri, Dist Ahmednagar (Maharashtra

www.ijird.com May, 2013 Vol 2 Issue 5 ISSN: 2278 – 0211 (Online) A Preliminary Study On Death Of Fish Chela Sp. (Hamilton) In Dyneshawar Sagar Mulanagar, Rahuri, Dist Ahmednagar (Maharashtra) Dr. S. V. Chaudhari Associate Professor, Department Of Zoology Arts, Science & Commerce College, Rahuri,India Abstract: The total area brought under fish culture in the Ahmednagar district is 2,552 hectares. Dyneshawar sagar (Mula dam), Mulanagar, Rahuri is one of the major fresh water resources used for natural & artificial fishing. Fishing nets found to be used for fishing. Besides fishing nets; fish baits, dynamite palates may possibly used for fishing that may be the reason of death of fish Chela sps. In the present project survey conducted to collect the dead fishes along the bank of darn water. The water of mula dam also being polluted by local tourist. This study only highlights toward the irrational, cruel methods of fishing and cruelty against fishes and other aquatic animals. Key words: dyneshawar sagar, rahuri, fish death, Chela sp. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT Page 1082 www.ijird.com May, 2013 Vol 2 Issue 5 1.Introduction Maharashtra State is endowed with 3, 77,905 ha. Water spread area under 192 large & medium projects, 2065 minor irrigation projects and 31,415 zilla parishad tanks. Excluding protected water bodies 3, 18,548 ha. Water spread area has been brought under fish culture. To avail the quality fish seed of Indian Major Carps (IMC) and exotic carps State Govt. has established centers, out of which 28 centers have circular hatchery setup. Fresh Water Fishery in Maharashtra State more or less 6 varieties of fishes like Indian Major Carps - Catla, Rohu, Mrugal, Exotic carps- Silver carp, Grass carp, common carp-Cyprinus. -

Proposed New National Highway -NH-160D (Feeder Route Of

PRE-FEASIBILTY REPORT (PFR) For ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (EMP) For Proposed New National highway -NH-160D (Feeder Route of Bharatmala Project Route 4 starts from Junction of NH-60 near Nandur Shingote District- Nashik connecting Dighe, Talegaon, Loni and terminating at its junction with NH-160 near Kolhar in District-Ahmednagar (approximately 48.70 km) SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA (Ministry of Road Transport & Highways Government of India) PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT OF BHARATMALA ROUTE 4: NANDUR SHINGOTE TO KOLHAR (48.7 KM) 03/16/2018 Table of Content 1. Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction of the Project / Background information ..................................................... 6 i. Identification of Project and Project Proponent .......................................................................... 6 ii. Brief Description of nature of the Project..................................................................................... 6 iii. Need for the Project and its importance to the Country and or region ................................. 6 iv. Demand Supply Gap ................................................................................................................... 7 v. Imports vs. Indigenous production ................................................................................................ 7 vi. Export Possibility .......................................................................................................................