Lake Ontario Maritime Cultural Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavating the Past

What Lies .28 10 Beneath 01 01/ Early hunters in the Toronto region would have sought high vantage points, such as shoreline cliffs, to track herds of caribou and other large game. IMAGE/ Shelley Huson, Archaeological Services Inc. 02/ 11,000-year-old stone points IMAGE/ Museum of Ontario Archaeology, Wilfrid Jury Collection 03/ A 500-year-old human effigy that adorned a ceramic pipe IMAGE/ Andrea Carnevale, Archaeological Services Inc. 04/ A 2,500-year-old artifact made of banded slate IMAGE/ Museum of Ontario Archaeology, Wilfrid Jury Collection Excavating the past TEXT BY RONALD F. WILLIAMSON AND SUSAN HUGHES What Lies .28 11 Beneath For more than 13,000 years, southern in Ontario require archaeological assess - planning guidelines for their management. Ontario has been home to indigenous ments, which are mandated by the Many regional municipalities, such as populations. These indigenous peoples Provincial Policy Statement, for projects Ottawa, Durham, York, and Halton, and once occupied thousands of encampments within their jurisdictions. cities such as Kingston, Toronto, Brantford, and temporary villages. They left no written London, and Windsor, among others, have record of their lives, and their legacy Some projects, however, may not undertaken archaeological management consists of the oral histories and traditions “trigger” a permit requirement. In these plans. In these municipalities, planners passed on to their descendants, as well instances, due diligence is critical, because use the potential mapping to decide which as the archaeological traces of their settle - encountering an archaeological feature projects require assessments. ments. These traces are fragile: whenever during project work can result in costly you dig in the ground, you could be delays. -

A Review of Northern Iroquoian Decorated Bone and Antler Artifacts: a Search for Meaning

Williamson and Veilleux Iroquoian Decorated Bone and Antler Artifacts 3 A Review of Northern Iroquoian Decorated Bone and Antler Artifacts: A Search for Meaning Ronald F. Williamson and Annie Veilleux The Northern Iroquoian practice of producing finely etched designs on bone and antler tools is examined in the context of conveying symbolic messages, some of which were communicated both privately and pub- licly. This paper presents the results of a review of the archaeological literature, which focused on both the symbolism inherent in the designs and the ideological roles in society of the animals from which the arti- facts were produced. Tables of provenience and descriptive attribute data are provided for each class of arti- fact as well as a summary of the highlights and trends in decoration for each. Introduction Trigger 1976:73), it has been suggested that their disc-shape may have been intended to represent In the winter of 1623-1624, Gabriel Sagard, a the sun and that patterns such as the one in Recollet friar, visited the country of the Huron in Figure 1, found on a late fifteenth or early six- what is now southern Ontario and, based on a teenth century Iroquoian site in southwestern series of encounters the Huron had with their ene- Ontario, represent sunbursts, similar to those mies, he noted that after having clubbed their ene- that are common in the art and cosmology of the mies or shot them dead with arrows, the Huron contemporaneous Southeastern Ceremonial carried away their heads (Wrong 1939:152-153). Complex (Cooper 1984:44; Jamieson1983:166). -

Trout Stockers Big and Small Conestogo at Work

The Grand River watershed newsletter May/June 2014 • Volume 19, Number 3 What’s Inside: Features Trout Stockers . 1 Heritage River About the heritage rivers . 3 Taking Action Race director award . .4 Tree planting . 5 Doon valley . 5 Now Available Waterloo county tours . 6 Foundation Natural playground . 6 What’s happening REEP’s RAIN program . 7 Summer camps . 7 Trout stockers big and small Conestogo at work . 8 Calendar . 8 By Janet Baine a few hours away. GRCA Communications Specialist The fish can survive only for a short time after or 12 springs, Waterloo resident Brad Knarr the long trip from the hatchery. There is a rush to get them into the river quickly to give them the has volunteered to organize the brown trout Cover photo F best possibility of survival. release into the Conestogo River. Community members stock Dozens of volunteers show up set for a full day fish in Mill Creek, Cambridge, An electrician by trade, Knarr is also a keen of work no matter the weather on fish stocking each year. angler. It takes him a week of legwork to get ready days. They are members of Friends of the Grand Photo by Robert Messier. for the two stocking days when thousands of River and the Conestogo River Enhancement small fish arrive at the river. Workgroup (CREW) as well as others who want to “It’s my way of giving back to the fish and the help. For example, staff from Google’s Kitchener river,” says Knarr, who is quick to add that he has office spend the day stocking fish using rented no intention of giving up his volunteer position. -

Reviews Skeleton: Some Thoughts on the Relocation of Cultural Heritage Disputes” (Gerstenblith)

159 Reviews Skeleton: Some Thoughts on the Relocation of Cultural Heritage Disputes” (Gerstenblith). Douglas Owsley and Richard Jantz interpret the Kennewick case as “a clash Edited by Charles R. Ewen between two systems of conceptualizing and tracing human history” (p. 141), although they assert that the origin of the lawsuit lies more with a lack of compliance with existing laws than with the ideological battle. In their chapter they Claiming the Stones/Naming the Bones: describe in great detail the myriad of research questions that Cultural Property and the Negotiation of the Kennewick skeleton raises and could potentially answer National and Ethnic Identity with further scientifi c study. ELAZAR BARKAN AND RONALD BUSH Patty Gerstenblith’s article, on the other hand, frames (EDITORS) the Kennewick case (and NAGPRA as a whole) in terms of social justice—returning to marginalized groups some Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, control over their own pasts (and thus their cultural identi- CA, 2003. 384 pp., 33 illus., index. $50.00 ties). She argues from a particularistic stance, outlining the paper. long history that has served to disconnect Native American groups from their cultural patrimony through a privileging Claiming the Stones/Naming the Bones is a timely volume of scientifi c evidence while simultaneously, through displace- that attempts to crosscut multiple disciplines (including ment and policies of cultural eradication, making it diffi cult archaeology, physical anthropology, literature, cultural stud- obtain such evidence. ies, ethnomusicology, and museum studies) and offer per- Neither Owsley and Jantz nor Gerstenblith overtly draw spectives regarding disputes over the defi nition and owner- attention to global vs. -

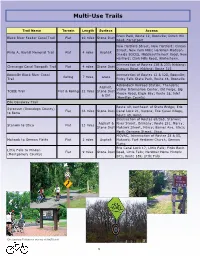

Multi-Use Trails

Multi-Use Trails Trail Name Terrain Length Surface Access Erwin Park, Route 12, Boonville; Dutch Hill Black River Feeder Canal Trail Flat 10 miles Stone Dust Road, Forestport New Hartford Street, New Hartford; Clinton Street, New Y ork Mills; Herkimer- Madison- Philip A. Rayhill Memorial T rail Flat 4 miles Asphalt Oneida BOCES, Middlesettlement Road, New Hartford; Clark Mills Road, Whitestown. Intersection of Routes 12B & 233; Kirkland; Chenango Canal Towpath Trail Flat 4 miles Stone Dust Dugway Road, Kirkland; Route 315, Boonville Blac k River Canal Intersection of Routes 12 & 12D, Boonville; Rolling 7 miles Grass Trail Pixley Falls State Park, Route 46, Boonville Adirondack Railroad Station, Thendara; Asphalt, Visitor Information Center, Old Forge; Big T OBIE T rail Flat & Rolling 12 miles Stone Dust Moose Road, Eagle Bay; Route 28, Inlet & Dirt (Hamilton County) Erie Canalway T rail Route 49, northeast of State Bridge; Erie Syracuse (Onondaga County) Flat 36 miles Stone Dust Canal Lock 21, Verona; Erie Canal Village, to Rome Rout e 49, Rome Intersection of Routes 69/365, Stanwix; Asphalt & River Street, Oriskany; Route 291, Marcy; Stanwix to Utic a Flat 13 miles Stone Dust Mohawk Street, Marcy; Barnes Ave, Utica; North Genesee Street, Utica MOVAC, Intersection of Routes 28 & 5S, Mohawk to German Flatts Flat 2 miles Asphalt Mohawk; Fort Herkimer Churc h, German Flatts Erie Canal Lock 17, Little Falls; Finks Basin Little Falls to Minden Flat 9 miles Stone Dust Road, Little Falls; Herkimer Home Historic (Montgomery County) Site, Route 169, Little Falls Erie Canalway Trail photos courtesy of HOCTS staff 6 Black River Feeder Canal Trail See Maps E and E-1 The approximately 10-mile Black River Feeder Canal trail is part of a New York State Canal Cor- poration improvement project to rehabilitate the towpath that follows the Black River Feeder Ca- nal. -

Anthropology (AN) 1

Anthropology (AN) 1 AN-262 Primate Behavior, Evolution and Ecology Credits: 3 ANTHROPOLOGY (AN) Term Offered: Spring Term Course Type(s): None AN-103 Cultural Anthropology Credits: 3 The study of primatology, which examines the lifeways, biology, and Term Offered: All Terms behavior of our closest living relatives. Various topics will be explored Course Type(s): SS.SV including taxonomy and classification, diet, behavior, grouping patterns, Introduction to comparative study of human beliefs and behavior. locomotion, and land usage patterns of monkeys, apes and prosimians. Emphasis on the concepts used in studying human culture; analysis These topics will be explored within the frameworks of natural selection, of non-Western societies with respect to ecology, economy, social and sexual selection, and evolution. Also listed as BY-262. political organization, religion, and art; implications for American society. AN-263 Peoples and Cultures of South America Credits: 3 AN-104 Introduction to Biological Anthropology Credits: 3 Prerequisite(s): AN-103 or AN-113 Term Offered: All Terms Course Type(s): RE Course Type(s): HE.EL, HEPE, SS.SV A social and cultural survey of representative peoples in South America Introduction to physical anthropology; racial variation and the and the Caribbean, emphasizing the comparative study of economic, evolutionary origins of the human species; concepts and principles used political, social, and religious organization. in the study of living and fossil evidence for human evolution and genetic AN-264 North American Indians Credits: 3 diversity; unique influence of culture on human biology; human evolution Term Offered: All Terms in the present and future. Course Type(s): GU, RE AN-107 Introduction to Archaeology Credits: 3 A survey of the cultural, social and linguistic diversity of Pre-Columbian Term Offered: All Terms North American societies; problems of contemporary Indian groups. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

B) Northeastern Regional Profiles

Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles b) Northeastern Regional Profiles The Northeastern Region identified for the Oneida County Hazard Mitigation Plan includes the following municipalities: The Town of Ava The Town and Village of Boonville The Town of Forestport The Town and Village of Remsen The Town of Steuben, and The Town of Western. Northeastern Regional Map A Page 1 of 33 Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles Regional Map B: 2013 Land Use in the Northeastern Region Page 2 of 33 Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles Regional Map C: New parcels since 2007. These communities tend to be dominated by rural landscapes and large wooded parcels. The region tends to be sparsely populated with an average population density of 36.5 persons per square mile with Ava at the low end of the spectrum at 17.95 and the Town of Boonville at the high end of the spectrum at 63.37. As a portion of the region is located within the Tughill Plateau, heavy rates of snowfall are not uncommon. While these communities tend to be well prepared for a snow storm that may cripple other areas, there is now also an awareness for the potential for severe damages from hurricanes, landslides and ice storms and severe storms. Flooding related to stormwater is an issue of concern in developed areas such as the Village of Remsen where widespread property damage has occurred on multiple occasions. -

Oriskany:Aplace of Great Sadness Amohawk Valley Battelfield Ethnography

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Ethnography Program Northeast Region ORISKANY:APLACE OF GREAT SADNESS AMOHAWK VALLEY BATTELFIELD ETHNOGRAPHY FORT STANWIX NATIONAL MONUMENT SPECIAL ETHNOGRAPHIC REPORT ORISKANY: A PLACE OF GREAT SADNESS A Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography by Joy Bilharz, Ph.D. With assistance from Trish Rae Fort Stanwix National Monument Special Ethnographic Report Northeast Region Ethnography Program National Park Service Boston, MA February 2009 The title of this report was provided by a Mohawk elder during an interview conducted for this project. It is used because it so eloquently summarizes the feelings of all the Indians consulted. Cover Photo: View of Oriskany Battlefield with the 1884 monument to the rebels and their allies. 1996. Photograph by Joy Bilharz. ExEcuTivE SuMMARy The Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography Project was designed to document the relationships between contemporary Indian peoples and the events that occurred in central New York during the mid to late eighteenth century. The particular focus was Fort Stanwix, located near the Oneida Carry, which linked the Mohawk and St. Lawrence Rivers via Wood Creek, and the Oriskany Battlefield. Because of its strategic location, Fort Stanwix was the site of several critical treaties between the British and the Iroquois and, following the American Revolution, between the latter and the United States. This region was the homeland of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy whose neutrality or military support was desired by both the British and the rebels during the Revolution. The Battle of Oriskany, 6 August 1777, occurred as the Tryon County militia, aided by Oneida warriors, was marching to relieve the British siege of Ft. -

A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography for the Secondary Teacher

LOCDMENT RESUME ED 084 067 RC 007 450 TITLE North American Indians; A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography for the Secondary Teacher. INSTITUTION Arizona State Univ., Tempe. Indian Education Center. PUB DATE Feb 73 NOTE 126p. AVAILABLE FROM Mr. George A. Gill, Center for Indian Education, Farmer College of Education, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Annotated Bibliographies; Books; Culture; Demography; History; *Literature Reviews; *Secondary School Teachers; Tribes ABSTRACT Approximately 1,490 books and articles published between 1871-1971 are listed in this annotated bibliography on th,J North American Indian. The bibliography is primarily for secondary teachers and educators and those who are concerned about securing materials relating to American Indians. (IF) t. NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography for the SECONDARY TEACHER at CENTER FOR INDIAN EDUCATION College of Education Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona TABLE OF C ONTENTS Author/Editor Page A 1 B Li C 15 D 22 23 31 36 II 41 51 J 53 57 L 62 N 67 77 O 81 P C4 O 90 91 S 97 T 105 U 110 112 t\T 115 122 7 123 INTPODUCTIO N This annotated bibliography is nrimarilyfor teachers and educators on thesecondary level, and above, who are concernedabout securing materials relating to the NorthAmerican Indian. Acknowledgement is given to the Arizona StateUniversity 1971 fall students In IE 411 (Indian Fducation,IL 424(Curriculum and Practices for Indian Education) and IE 544 (CommunityDevelopment in Indian Education) fortheir classroom contributions. Special thanks is also extended to the Center'sgraduate assist- ants Deborah Golub, Lana Shaughnessy and SheilaMcKenzie for their extensive work and dedication in the preparation ofthis bibliography. -

NYSSA Bulletin 131-132 2017-2018

David R. Starbuck, Editor ISSN 1046-2368 The New York State Archaeological Association2018 Officers Lisa Marie Anselmi, President David Moyer, Vice President Gail Merian, Secretary Ann Morton, Treasurer The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the publisher. Published by the New York State Archaeological Association. Subscription by membership in NYSAA. For membership information write: President Lisa Anselmi, [email protected]; 716 878-6520 Back numbers may be obtained from [email protected]; 716 878-6520 Or downloaded from the NYSAA website http://nysarchaeology.org/nysaa/ Entire articles or excerpts may be reprinted upon notification to the NYSAA. Manuscripts should be submitted to Dr. David Starbuck, P.O. Box 492, Chestertown, NY 12817. If you are thinking of submitting an item for publication, please note that manuscripts will be returned for correction if manuscript guidelines (this issue) are not followed. Authors may request peer review. All manuscripts submitted are subject to editorial correction or excision where such correction or excision does not alter substance or intent. Layout and Printing Mechanical Prep, Publishing Help by Dennis Howe, Concord, New Hampshire Printed by Speedy Printing, Concord, New Hampshire. Copyright ©2018 by the New York State Archaeological Association Front Cover Photographs The collage of photographs on the front cover are taken from several of the articles in this issue of The Bulletin, which are devoted to the growth and development of the New York State Archaeological Association (NYSAA) over the last hundred years. The collage is a small representation of the many men and women from diverse disciplines who made major archaeological discoveries, established scientific approaches to archaeological studies, and contributed to the formation of NYSAA. -

SHS Newsletter – Jun 2016

ANNUAL WALKING TOUR: Saturday, June 4th 2016 START TIME: 1:30 pm - The walk will start in Neil McClellan Park on the west side of Runnymede Road, across from the Runnymede subway station, and finish with refreshments at the Swansea Town Hall TOPIC: An Introduction to Swansea – Still a Community The Swansea Historical Society thankfully acknowledges funding grants from the following provincial bodies: President's Message by Bob Roden, President We have had a very eventful and exciting year, and I want to extend a sincere thank-you to all those who made it happen. The May 4 meeting was our last formal meeting before the summer break. We will start up again in October with our Annual General Meeting and elections, and we have a full slate of interesting speakers confirmed for the 2016-2017 programme year. In the meantime, we will be participating in several neighbourhood events, which we invite you to attend, including various guided historical walking tours. We hope to see you at our walking tours on June 4 and August 13, which will be led by Lance Gleich. Also, we plan to set up information tables at the Bloor West Village Sidewalk Sale on June 18 and the Montgomery's Inn Corn Roast & Heritage Fair on September 8, and we are seeking volunteers to take a shift at the SHS table for either one or both of those dates. See “Future Events” below, for more details on all of these happenings. Both Heritage Toronto (heritagetoronto.org/programs/tours) and the Royal Ontario Museum (www.rom.on.ca/en/whats-on/romwalks) offer guided walking tours throughout the season.