Diplomarbeit / Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examensarbete Institutionen För Ekologi Lynx Behaviour Around

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epsilon Archive for Student Projects Examensarbete Institutionen för ekologi Lynx behaviour around reindeer carcasses Håkan Falk INDEPENDENT PROJECT, BIOLOGY LEVEL D, 30 HP SUPERVISOR: JENNY MATTISSON, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION COSUPERVISOR: HENRIK ANDRÉN, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION EXAMINER: JENS PERSSON, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION Examensarbete 2009:14 Grimsö 2009 SLU, Institutionen för ekologi Grimsö forskningsstation 730 91 Riddarhyttan 1 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet/Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences NL-fakulteten, Fakulteten för naturresurser och lantbruk/Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Institutionen för ekologi/Department of Ecology Grimsö forskningsstation/Grimsö Wildlife Research Station Författare/Author: Håkan Falk Arbetets titel/Title of the project: Lynx behaviour around reindeer carcasses Titel på svenska/Title in Swedish: Lodjurs beteende vid renkadaver Nyckelord/Key words: Lynx, reindeer, wolverine, predation, scavenging Handledare/Supervisor: Jenny Mattisson, Henrik Andrén Examinator/Examiner: Jens Persson Kurstitel/Title of the course: Självständigt arbete/Independent project Kurskod/Code: EX0319 Omfattning på kursen/Extension of course: 30 hp Nivå och fördjupning på arbetet/Level and depth of project: Avancerad D/Advanced D Utgivningsort/Place of publishing: Grimsö/Uppsala Utgivningsår/Publication year: 2009 Program eller utbildning/Program: Fristående kurs Abstract: The main prey for lynx in northern Sweden is semi-domestic reindeer. Lynx often utilise their large prey for several days and therefore a special behaviour can be observed around a kill site. The aim of this study was to investigate behavioural characteristics of lynx around killed reindeer and examine factors that might affect the behaviour. -

The Scandinavian Brown Bear Summary of Knowledge and Research Needs

THE SCANDINAVIAN BROWN BEAR SUMMARY OF KNOWLEDGE AND RESEARCH NEEDS Report to the Wildlife Research Committee, Swedish Environmental Protection Agency Scandinavian Brown Bear Research Project Report 2007-1 By Jon E. Swenson Department of Ecology and Natural Resources Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences Box 5003 NO-1432 Ås, Norway & Norwegian Institute for Nature Research 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 3 THE SCANDINAVIAN BROWN BEAR RESEARCH PROJECT 4 History 4 Structure, cooperators and financing organizations 4 The International Review Committee 6 Data and the database 7 SYNTHESIS OF PRESENT KNOWLEDGE 9 The colonization of Scandinavia by brown bears 9 The decline and subsequent recovery of brown bears in Scandinavia 9 Present population size and trend 10 The demographic and genetic viability of the Scandinavian brown bear population 11 Behavioral ecology and life history 13 Foraging ecology 16 Bear-human conflicts 17 Predation on moose 17 Depredation on sheep 18 Fear of bears 19 Human disturbance of bears and their avoidance of humans 19 The management of bear hunting 20 The development and testing of field methods 22 Brown bears as a model for large carnivore conservation in human-dominated landscapes 23 FUTURE RESEARCH NEEDS 24 Population estimation and monitoring 25 Harvesting bear populations 26 Genetics 27 Density-dependent effects on brown bear population ecology and life-history traits 27 Factors promoting and hindering population expansion 28 Bear-human conflicts when a bear population expands 29 Bears -

Chapter 2 High Mountains in the Baltic Sea Basin

Chapter 2 High mountains in the Baltic Sea basin Joanna Pociask-Karteczka 1, Jarosław Balon 1, Ladislav Holko 2 1 Institute of Geography and Spatial Management, Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, [email protected] 2 Institute of Hydrology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovakia Abstract : The aim of the chapter is focused on high mountain regions in the Baltic Sea basin. High mountain environment has specific features defined by Carl Troll. The presence of timberline (upper tree line) and a glacial origin of landforms are considered as the most important features of high mountains. The Scandianavian Mountains and Tatra Mountains comply with the above definition of the high mountain environment. Both mountain chains were glaciated in Pleistocene : the Fennos- candian Ice Sheet covered the northern part of Europe including the Scandinavian Peninsula while mountain glaciers occurred in the highest part of the Carpathian Mountains. Keywords : U-shaped valleys, glacial cirques, perennial snow patches, altitudinal belts The Baltic Sea and its drainage The Baltic Sea occupies a basin formed by glacial basin – general characteristic erosion during three large inland ice ages. The latest and most important one lasted from 120,000 until ap. The Baltic Sea is one of the largest semi-enclosed seas 18,000 years ago. The Baltic Sea underwent a complex in the world. The sea stretches at the geographic lati- development during last several thousand years after tude almost 13° from the south to the north, and at the the last deglaciation. At present it exhibits a young geographic longitude 20° from the west to the east. -

Lunds Universitets Naturgeografiska Institution Seminarieuppsatser Nr. 66

Lunds Universitets Naturgeografiska Institution Seminarieuppsatser Nr. 66 _______________________________________________ Climate conditions required for re-glaciation of cirques in Rassepautasjtjåkka massif, northern Sweden Margareta Johansson _______________________________________________ 2000 Department of Physical Geography, Lund University Sölvegatan 13, S-221 00 Lund, Sweden TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT_________________________________________________________________ 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT _____________________________________________________ 4 1 INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________________ 5 1.1 BACKGROUND ___________________________________________________________ 5 1.2 AIM OF THE STUDY _______________________________________________________ 6 2 AREA DESCRIPTION____________________________________________________ 7 3 THEORY _______________________________________________________________ 9 3.1 DEFINITION OF A GLACIER__________________________________________________ 9 3.2 MELT CONDITION ________________________________________________________ 9 3.3 MODEL DESCRIPTION ____________________________________________________ 10 4 METHOD______________________________________________________________ 12 4.1 FIELD MEASUREMENTS AND FIELDWORK _____________________________________ 12 4.2 INPUT DATA TO THE MODEL _______________________________________________ 12 4.2.1 Input climate data and evaluation of the climate data with data from Tarfala ___ 13 4.2.2 DEM and DTM _____________________________________________________ 14 -

Tourism Labor Market Impacts of National Parks 115 Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie Jg

Joakim Byström / Dieter K. Müller: Tourism labor market impacts of national parks 115 Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie Jg. 58 (2014) Heft 2-3, S. 115–126 Joakim Byström / Dieter K. Müller, Umeå/Sweden Tourism labor market impacts of national parks The case of Swedish Lapland Joakim Byström / Dieter K. Müller: Tourism labor market impacts of national parks Abstract: In a Nordic context, economic impacts of tourism in national parks remained largely un- known due to lacking implementation of standardized comparative measurements. For this reason, we want to investigate the economic impacts of national parks in a peripheral Scandinavian context by analyzing employment in tourism. Theoretically, the paper addresses the idea of nature protection as a tool for regional development. The scientific literature suggests that nature can be considered a commodity that can be used for the production of tourism experiences in peripheries. In this context nature protection is applied as a label for signifying attractive places for tourists leading to increased tourist numbers and employment. This argument follows mainly North American experiences point- ing at a positive impact of protected areas on regional development. Meanwhile European studies are more skeptical regarding desired economic benefits. A major challenge is the assessment of tourism’s economic impacts. This paper suggests an approach that reveals the impacts on the labor market. This is particularly applicable since data is readily available and, moreover from a public perspective, employment and tax incomes are of uppermost importance in order to sustain population figures and local demand for public services. At the same time accessibility and low visitor numbers form major challenges for tourism stakeholders and complicate the assessment of economic impacts through questionnaires and interviews. -

Tiina Laantee, Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 17185 Solna, Sweden Tel: +46 8 7991000 Fax: +46 8 291106 Name of Wetland: Laidaure

INFORMATION SHEET ON RAMSAR WETLANDS Country: Sweden Date: December 1991 Ref: 7SE018 Name and address of compiler: Tiina Laantee, Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 17185 Solna, Sweden Tel: +46 8 7991000 Fax: +46 8 291106 Name of wetland: Laidaure Date of Ramsar designation: 5 December 1974 Geographical coordinates: 67°07'N 17°45'E General location: About 90 km north-west of the town of Jokkmokk and on the south-eastern border of Sarek National Park, in the county of Norrbotten. Area: 4,150 ha Wetland type: L M O W Altitude: Average of 507 m above sea level. Overview: The site lies between the mountainous region of Sarek National Park and a zone of coniferous forests. It comprises Lake Laidaure, into which the delta of the River Rapa is rapidly expanding. The delta is the most important bird locality in the Sarek region and is especially important as a breeding ground for duck. Physical features: The site comprises Lake Laidaure, into which the delta of the River Rapa is rapidly expanding at the eastern end. The river transports high quantities of mud from the glaciers of the Sarek region. Lagoons and levees are common in the delta, which mainly consists of sandy soils. Ecological features: Salix thickets grow on the levees, and on higher levels there are woods of Betula. Land tenure/ownership of a) site: Ownership is divided between the State, the Swedish nature Conservation Society and private owners. b) surrounding area: no information supplied. Conservation measures taken: Listed as site of national importance to nature conservation. Part of the designated site (300 ha) in the region of the River Rapa delta is included in Sarek National Park, established 24 May 1909. -

Gos Sarek Ladies

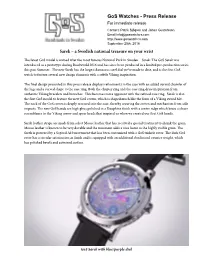

GoS Watches - Press Release For immediate release Contact: Patrik Sjögren and Johan Gustafsson Email [email protected] http://www.goswatches.com September 20th, 2016 Sarek Ladies - a Swedish national treasure on your wrist Damascus steel is generally thought of as being raw and unpolished. However, GoS has shown that it is possible to manufacture elegant and exclusive watches from our hand forged steel and we are proud to announce the first GoS ladies watch. The Sarek adies is the first ever women!s watch with a damascus steel dial. Johan Gustafsson has a unique ability to extract natural vibrant colors from his hand forged steel, which we use in the Sarek to the fullest. The idea of $%&'()*+%,-./0*1%0/2*3(*%*4%,'3(%5*6%7&*+%0*'(','%,/2*%(2*2/8/539/2*1:*6%,7'&*;<=)7/(*%(2*>3.%(*?@0,%A003(* during the winter of BCDEFBCDG and introduced with a prototype of a Sarek men!s watch during Haselworld BCDG. GoS then continued to develop the men!s watch but also started to work on a ladies model. The ladies model shares some of the Iiking inspired details that were introduced with the men!s Sarek while adding new details such as the strap screws. The elliptic grooves on the case ring which GoS premiered on the men´s Sarek have been made more elegant and the whole case is high gloss polished. Knother striking difference us the index markers of Sarek adies, which opened to show the colored steel below. The slightly sloped case interior provides more light to the indexes and provides a surface on which the colored damascus steel is reflected. -

Scandinavian Autumn: Sweden-Norway

Scandinavian Autumn: Sweden-Norway About 5 weeks beginning mid August 2014 This trip was inspired by our 2012 trip where the major walk was in Sarek & Padjelanta National Parks. On that trip I discovered the Swedish and Norwegian mountain ‘huts’. The two photos at left show one of the huts we passed in Padjelanta from the outside and inside. Other huts were similar. In 2012, we went at the height of summer when it never got completely dark. We carried tents and camped out. Occasionally we had to pitch tents or pack up in the rain – rather chilly north of the arctic circle. By starting five weeks later and doing walks where we stay in huts, we should be able to enjoy some of the spectacular scenery without having to carry as much weight as we did in 2012. We should get to enjoy the autumn vegetation as green turns into a rainbow of colours. And, if we are lucky and are awake at the appropriate hour, we may see the northern lights. In 2012, we began with a night train from Göteborg (Gothenburg in English). We paid a bit extra and had sleeping compartments. This allowed us to get good views of the Swedish landscape, and also get a feel for the distances. Kiruna, where we will get off the train is as far from Göteborg as Göteborg is from Paris. The bed and transport cost us less than A$200 in 2012. I thought it was good value. We plan to catch the train again. If you don’t want to start in Gothenburg, you can catch the same train in Stockholm. -

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in Sami Reindeer Herding: the Socio-Political Dimension of an Epizootic in an Indigenous Context

animals Article Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in Sami Reindeer Herding: The Socio-Political Dimension of an Epizootic in an Indigenous Context Simon Maraud * and Samuel Roturier Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, AgroParisTech, Ecologie Systématique Evolution, 91405 Orsay, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Chronic wasting disease (CWD), the most transmissible of the prion diseases, was detected in 2016 in Norway in a wild reindeer. This is the first case in Europe, an unexpected one. This paper focuses on the issues that the arrival of CWD raises in Northern Europe, especially regarding the Indigenous Sami reindeer husbandry in Sweden. The study offers a diagnosis of the situation regarding the management of the disease and its risks. We present the importance of the involvement of the Sami people in the surveillance program in order to understand better the diseases and the reindeer populations, movement, and behavior. However, the implementation of new European health standards in the Sami reindeer herding could have tremendous consequences on the evolution of this ancestral activity and the relationship between herders and reindeer. Abstract: Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is the most transmissible of the prion diseases. In 2016, an unexpected case was found in Norway, the first in Europe. Since then, there have been 32 confirmed cases in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. This paper aims to examine the situation from a social and political perspective: considering the management of CWD in the Swedish part of Sápmi—the Sami Citation: Maraud, S.; Roturier, S. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in ancestral land; identifying the place of the Sami people in the risk management–because of the threats Sami Reindeer Herding: The to Sami reindeer herding that CWD presents; and understanding how the disease can modify the Socio-Political Dimension of an modalities of Indigenous reindeer husbandry, whether or not CWD is epizootic. -

Strasbourg, 17 December 2001 PE-S-DE (2002) 14 COMMITTEE

Strasbourg, 17 December 2001 PE-S-DE (2002) 14 [diplôme/docs/2002/de14e_02] COMMITTEE FOR THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE IN THE FIELD OF BIIOLOGICAL AND LANDSCAPE DIVERSITY (CO-DBP) Group of specialists – European Diploma for Protected Areas 28-29 January 2002 Room 15, Palais de l'Europe, Strasbourg Sarek and Padjelanta National Parks (Sweden) RENEWAL Expert report by Mr Hervé Lethier, EMC2I Agency (Switzerland) Document established by the Directorate of Culture and Cultural and Natural Heritage ___________________________________ This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. PE-S-DE (2002) 14 - 2 - The European Diploma for protected areas (category A) was awarded to the Sarek and Padjelanta National Parks in 1967 and has been renewed since then. The Secretariat did not accompany the expert on his visit to the site. Appendix 3 reproduces Resolution (97) 15 adopted when the Diploma was last renewed. Appendix 4 sets out a draft resolution prepared by the Secretariat for the purpose of extending * * * * * ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present report has been drawn up on the basis of appraisal information gathered on the spot by the expert. The views expressed are solely those of the author, who thanks all the individuals he met on his visit for their valuable assistance, particularly Jan Stuge1, Asa Lagerlof2 and Bengt Landström3, who accompanied him throughout his visit. St Cergue, 26 November 2001 1 Mountain unit. 2 Swedish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA). 3 Länsstyrelsen I Norrbottens Län. - 3 - PE-S-DE (2002) 14 GENERAL POINTS The aim of the visit was to make an appraisal for the renewal of the European Diploma held jointly by the Sarek and Padjelanta National Parks, Sweden4. -

Map of the Multiple Designations / Certifications Awarded to Diploma Holding Areas

Strasbourg, 18 February 2019 T-PVS/DE (2019) 7 [de07e_2019.doc] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 39th meeting Strasbourg, 3-6 December 2019 Group of Specialists on the European Diploma for Protected Areas MAP OF THE MULTIPLE DESIGNATIONS / CERTIFICATIONS AWARDED TO DIPLOMA HOLDING AREAS Document prepared by the Directorate of Democratic Participation This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. N° Name Country Other certification/designation Hautes Fagnes Nature 1 Belgium Reserve National: Zones Naturelles d’Intérêt Ecologique Faunistique et Floristique (type 1 et type 2) Site classé (loi 1930) Site inscrit (loi 1930) Propriété du Conservatoire du littoral Parc naturel régional Camargue National 2 France Reserve International: Natura 2000 site Ramsar site UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (Man and Biosphere Programme) Important Bird Area (Birdlife International) National: National Park 61 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) 265 Scheduled Ancient Monuments Peak District National 70 Village Conservation Areas 3 United Kingdom Park Over 2000 Listed Buildings International: 3 Natura 2000 sites National: Natural Monument Part of the National Park Hohe Tauern (peripheral zone) Krimml Waterfalls 4 Austria Natural Site International: Part of a Natura 2000 site. Lüneburg Heath 5 Germany Nature Reserve National: National Park ”National Interest” in the Swedish Environmental -

Gos Sarek Update

GoS Watches - Press Release For immediate release Contact: Patrik Sjögren and Johan Gustafsson Email [email protected] http://www.goswatches.com September 20th, 2016 Sarek – a Swedish national treasure on your wrist The latest GoS model is named after the most famous National Park in Sweden – Sarek. The GoS Sarek was introduced as a prototype during Baselworld 20 ! and has since "een produced in a limited pre-production series this past Summer. The new Sarek has the largest damascus steel dial we've made to date, and is the first GoS watch to feature several new design elements with a subtle 'iking inspiration. The final design presented in this press release displays refinements in the case with an added curved chamfer of the lugs and a curved shape to the case ring. Both the chapter ring and the case ring draw inspiration from authentic 'iking "racelets and "rooches. This "ecomes more apparent with the refined case ring. Sarek is also the first GoS model to feature the new GoS crown& which is shaped much like the form of a 'iking sword hilt. The neck of the GoS crown is deeply recessed into the case& thereby securing the crown and mechanism from side impacts. The new GoS hands are high gloss polished in a (auphine finish with a center ridge which "ears a closer resem"lance to the 'iking arrow and spear heads that inspired us when we created our first GoS hands. Sarek leather straps are made from select Moose leather that has received a special treatment to shrink the grain.