The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians : Including Their

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joyous Christmas Observance

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.orgXCimee " •. The Watertown-Ookvills-MicMlcbury Weekly Timely Coverage Of News in The Fastest Growing Community In Litchfield County Price 10 Cents DECEMBER 21. 1967 VOL. 21 NO. .1041 Subscription Price, $3.75 Per Year Businessmen Launch Fund For Victim Of A ccident ice Slason, also of Porter St. A fund for 'the family of 10- 'The Slason girl was not struck. year-old Nancy-Clock, 82 Por- Waterbury Hospital authorities ter St., Who was critically -:1m.- said at presstime that 'the Clock - " Jured early Monday evening when girt Is to poor condition,' with • she .and. another young .girl were "her name on 'the danger list, struck by a car, has been started .She has been to 'the intensive by local 'businessmen. care unit since being admitted failed the Nancy 'Clock 'Fund, to' the hospital suffering from a, It will be used, to' help the fam- head Injury. ily with hospital expenses and Roberta Temple's condition was to provide them with aid during listed as fair. 'She sustained a the holiday season. Check should fractured right leg.: be made out to Nancy Clock Fund Police reported that the three and sent to the Watertown office girls were walking to. 'the gut- 'Of 'the Waterbury National Bank, ter, facing traffic, when they Woodruff A.ve. were struck by the Hresko car. - Nancy Is the daughter of Mrs. 'They said the Clock and Temple Henry Clock, _§2 Porter St. Her girls were thrown onto 'the hood. father succumbed suddenly sev- .. of the auto by the force of 'the eral weeks ago leaving Mrs. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Ancient Egypt

" r >' : : . ^-.uu"* , j *,.. ,'iiu,' ' .- ; * - »*i ,g^L^^A^v . ^H*M swv^ylliiTlTliU ™ jBlflPpl p. - illv i f *~ v* : ^ ~ * i iS , fUki. , w ,WIWW»UwYv A JU AjVk. w-^WW*K*wMAty wjvyv\ "Juffi ,»-"*>-"» , "**-"*' «jfe-*,'*i.<«.' > ' CONGRESS. sks^ ILIBRARY OF 5 ~"k ^.// * &6 UNITED STATES OE AMERICA. { y^Vw^y, v J • • * ^^^^0iMw:mm sum - < i ssssBEi J9« ;,y^*--. of y ^W^i J^A 3um3? . J\s\ , v L/,* ^M W$W*U*Aic^TiK^ " ;WJ^W^vJ*w% ^*W: re^V.Mw wm*mm v-W-cw- ' iVy »' i^jsJ^K^ ^ft$ta>W r|itf^ 1 1 , m u , w&mj SW£M«W Tenth Edition—Revised and corrected, with an Appendix, I ^ ANCIENT EGYPT. .HER MONUMENTS HIEROGLYPHICS, *£ HISTORY AND ARCHEOLOGY, AND OTHER SUBJECTS CONNECTED WITH HIEROGLYPHICAL LITERATURE BY GEORGE R. GLIDDON, LATE U. 8. CONSUL AT CAIRO. NEW-YORK : BALTIMORE: WM. TAYLOR &, CO., WM. TAYLOR <fc CO. No. 2, ASTOR HOUSE. Jarvis Building, North-st. London: PHILADELPHIA : WILEY & PUTNAM. G. B. ZIEBER & CO. SINGLE COPIES M TWENTY-FIVE CENTS I — ANCIENT EGYPT. Tenth Edition—Revised and corrected, with an Appendix. WM. TAYLOR & Co., Publishers. No. 2, ASTOR HOUSE, NEW-YORK ; AND JARVIS BUILDING, BALTIMORE. STEREOTYPE EDITION. January, 1847 PRICE 25 CENTS. At the time of your travels in the East, our " Egyptian Society " had just been founded at Cairo ; and the encouragement afforded by ANCIENT EGYPT. Mr. Randolph and yourself, to our then embryo institution, is there on record. Since that period, our Society has become in Egypt, the central point of researches into all that concerns its most interesting A SERIES OF CHAPTERS ON regions ; but, it was not till 1839, that the larger works of the new Archaeological School were in our library ; or that it was in my HISTORY, power to become one of Champollion's disciples. -

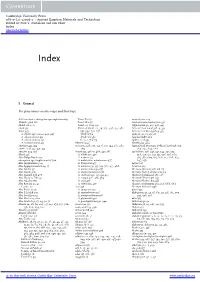

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

ORDOVICIAN to RECENT Edited by Claus Nielsen & Gilbert P

b r y o z o a : ORDOVICIAN TO RECENT Edited by Claus Nielsen & Gilbert P. Larwood BRYOZOA: ORDOVICIAN TO RECENT EDITED BY CLAUS NIELSEN & GILBERT P. LARWOOD Papers presented at the 6th International Conference on Bryozoa Vienna 1983 OLSEN & OLSEN, FREDENSBORG 1985 International Bryozoology Association dedicates this volume to the memory of MARCEL PRENANT in recognition o f the importance of his studies on Bryozoa Bryozoa: Ordovician to Recent is published by Olsen & Olsen, Helstedsvej 10, DK-3480 Fredensborg, Denmark Copyright © Olsen & Olsen 1985 ISBN 87-85215-13-9 The Proceedings of previous International Bryozoology Association conferences are published in volumes of papers as follows: Annoscia, E. (ed.) 1968. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Bryozoa. - Atti. Soc. ital. Sci. nat. 108: 4-377. Larwood, G.P. (cd.) 1973. Living and Fossil Bryozoa — Recent Advances in Research. — Academic Press (London). 634 pp. Pouyet, S. (ed.) 1975. Brvozoa 1974. Proc. 3rd Conf. I.B.A. - Docums Lab. Geol. Fac. Sci. Lvon, H.S. 3:1-690. Larwood, G.P. & M.B. Abbott (eds) 1979. Advances in Bryozoology. - Systematics Association, Spec. 13: 1-639. Academic Press (London). Larwood, G. P. «S- C. Nielsen (eds) 1981. Recent and Fossil Bryozoa. - Olsen & Olsen, Fredensborg, Denmark. 334 pp. Printed by Olsen £? Olsen CONTENTS Preface........................................................................................................................... viii Annoscia, Enrico: Bryozoan studies in Italy in the last decade: 1973 to 1982........ 1 Bigey, Françoise P.: Biogeography of Devonian Bryozoa ...................................... 9 Bizzarini, Fabrizio & Giampietro Braga: Braiesopora voigti n. gen. n.sp. (cyclo- stome bryozoan) in the S. Cassiano Formation in the Eastern Alps ( Italy).......... 25 Boardman, Richards. -

Tinteros De Bronce Romanos De Augusta Emerita ; Roman Bronze

Archivo Español de Arqueología 2019, 92, págs. 251-269 ISSN: 0066 6742 https://doi.org/10.3989/aespa.092.019.014 Tinteros de bronce romanos de Augusta Emerita Roman bronze inkpots from Augusta Emerita Javier Alonso1 Biblioteca Pública del Estado (Ciudad Real) Rafael Sabio González2 Museo Nacional de Arte Romano de Mérida José Manuel Jerez Linde3 Investigador independiente RESUMEN 1. INTRODUCCIÓN Estudio de tinteros de bronce recuperados en el yacimiento de Augusta Emerita. Se definen las partes de un tintero, En el transcurso de la revisión de materiales de diferentes tipologías, las medidas de volumen, se relacionan las época romana que se está llevando a cabo en el yaci- representaciones iconográficas de instrumentos de escritura con miento de Augusta Emerita, hemos podido reunir los hallazgos en depósitos funerarios, los usos de otros objetos una nada desdeñable colección de tinteros de bronce y componentes que implicaba escribir con tinteros y se analiza procedentes de las últimas intervenciones arqueoló- la relación de los tinteros con los depósitos funerarios y la posible identificación de quienes se enterraron con estos objetos. gicas, caso del Consorcio de la Ciudad de Mérida (CCMM), como también de los almacenes del Museo SUMMARY Nacional de Arte Romano (MNAR) y que se encua- dran dentro de los estudios que realizamos sobre la This article examines Roman metal inkwells found at cultura escrita en la capital de la Lusitania (Alonso Augusta Emerita. Along with the presentation of a typology, the y Velázquez 2010: 167-187; Sabio y Alonso 2012: parts of an inkwell are defined and volume measures are 1001-1023; Alonso 2013: 213-226; Alonso y Sabio analyzed. -

U Tech Glossary

URGLOSSARY used without permission revised the Ides of March 2014 glos·sa·ry Pronunciation: primarystressglässchwaremacron, -ri also primarystressglodots- Function: noun Inflected Form(s): -es Etymology: Medieval Latin glossarium, from Latin glossa difficult word requiring explanation + -arium -ary : a collection of textual glosses <an edition of Shakespeare with a good glossary> or of terms limited to a special area of knowledge <a glossary of technical terms> or usage <a glossary of dialectal words> Merriam Webster Unabridged tangent, adj. and n. [ad. L. tangens, tangent-em, pr. pple. of tangĕre to touch; used by Th. Fincke, 1583, as n. in sense = L. līnea tangens tangent or touching line. In F. tangent, -e adj., tangente n. (Geom.), Ger. tangente n.] c. In general use, chiefly fig. from b, esp. in phrases (off) at, in, upon a tangent, ie off or away with sudden divergence, from the course or direction previously followed; abruptly from one course of action, subject, thought, etc, to another. (http://dictionary.oed.com) As in off on a tangent. “Practice, repetition, and repetition of the repeated with ever increasing intensity are…the way.” Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel. For many terms, this glossary contains definitions from multiple sources, each with their own nuance, each authors variation emphasized. Reading the repeated definitions, with their slight variations, helps create a fuller, more overall understanding of the meaning of these terms. The etymology of the entries reinforces and may repeat the repetitions. Wax on, wax off. Sand da floor. For sometime, when I encounter a term I don’t understand (and there are very many), I have been looking them up in the oed and copying the definition into a Word document. -

European Pattern SAJJHAA B F 2007 SPLIT TROIS B F 2008 334 PREIS DER DEUTSCHEN 2004 : LUCIO BELLO (C Desert Prince) Winner at 2 2006 : (C a P Indy)

Dec_76_Databook:Leader 28/03/2011 18:11 Page 2 DATA BOOK Caulfield on Biondetti: “He became a first Group 1 winner for Darley stallion STAKES RESULTS Bernardini in the Gran Criterium, and he had another the same day in A Z Warrior” European Pattern SAJJHAA b f 2007 SPLIT TROIS b f 2008 334 PREIS DER DEUTSCHEN 2004 : LUCIO BELLO (c Desert Prince) Winner at 2 2006 : (c A P Indy). died as a foal. Margins 0.75, 1. Time 1:14.85 (slow 1.35). 2005 : FOR JOY (f Singspiel) 2 wins at 3 and 4 in October 9, 2010 was a big day for Raise A Native Mr Prospector in Greece. 2007 : MAKANI (c A P Indy) 2 wins at 2 and 3 in Mr Prospector Going Good to soft. France. Seeking The Gold Bernardini, America’s champion three- EINHEIT G3 Gold Digger Con Game 2005 : STRIKING SPIRIT (g Oasis Dream) 3 wins at France. Kingmambo 2006 : RANSOM DEMAND (c Red Ransom) Winner Dubai Millennium Nureyev Shareef Dancer year-old of 2006. The Darley stallion HOPPEGARTEN. October 3. 3yo+. 2000m. 2 and 4. 2008 : MAXIOS (c Monsun) 2 wins at 2 in France, Prix Miesque Age Starts Wins Places Earned at 3 in France. Colorado Dancer Pasadoble Fall Aspen recorded his first Gr1 victory when KING’S BEST b 97 DUBAWI b 2002 1. RUSSIAN TANGO (GER) 3 9-0 £28,319 2007 : EMULOUS (f Dansili) 2 wins at 2 and 3, Thomas Bryon G3 . Agio 2-3 14 63£158,867 2007 : Latinka (f Fantastic Light) Shirley Heights Lombard Deploy Biondetti travelled to Italy to take the ch c by Tertullian - Russian Samba (Laroche) Coolmore Stud Concorde S G3 , 2nd Kilboy 2009 : (c Dansili) Promised Lady 2008 : ABJER (c Singspiel) Sold 28,000gns yearling Slightly Dangerous Allegretta Zomaradah O- Rennstall Darboven B- Gestut Idee TR- A Wohler Estate S LR , 3rd Desmond S G3 . -

Alexandrea Ad Aegyptvm the Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity

Alexandrea ad aegyptvm the legacy of multiculturalism in antiquity editors rogério sousa maria do céu fialho mona haggag nuno simões rodrigues Título: Alexandrea ad Aegyptum – The Legacy of Multiculturalism in Antiquity Coord.: Rogério Sousa, Maria do Céu Fialho, Mona Haggag e Nuno Simões Rodrigues Design gráfico: Helena Lobo Design | www.hldesign.pt Revisão: Paula Montes Leal Inês Nemésio Obra sujeita a revisão científica Comissão científica: Alberto Bernabé, Universidade Complutense de Madrid; André Chevitarese, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; Aurélio Pérez Jiménez, Universidade de Málaga; Carmen Leal Soares, Universidade de Coimbra; Fábio Souza Lessa, Universidade Federal, Rio de Janeiro; José Augusto Ramos, Universidade de Lisboa; José Luís Brandão, Universidade de Coimbra; Natália Bebiano Providência e Costa, Universidade de Coimbra; Richard McKirahan, Pomona College, Claremont Co-edição: CITCEM – Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar «Cultura, Espaço e Memória» Via Panorâmica, s/n | 4150-564 Porto | www.citcem.org | [email protected] CECH – Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Humanísticos | Largo da Porta Férrea, Universidade de Coimbra Alexandria University | Cornice Avenue, Shabty, Alexandria Edições Afrontamento , Lda. | Rua Costa Cabral, 859 | 4200-225 Porto www.edicoesafrontamento.pt | [email protected] N.º edição: 1152 ISBN: 978-972-36-1336-0 (Edições Afrontamento) ISBN: 978-989-8351-25-8 (CITCEM) ISBN: 978-989-721-53-2 (CECH) Depósito legal: 366115/13 Impressão e acabamento: Rainho & Neves Lda. | Santa Maria da Feira [email protected] Distribuição: Companhia das Artes – Livros e Distribuição, Lda. [email protected] Este trabalho é financiado por Fundos Nacionais através da FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto PEst-OE/HIS/UI4059/2011 manetho and the history of egypt luís manuel de Araújo University of Lisbon. -

Transcripcio I Transliteracio Dels Noms Dels Principals Vasos Grecs

TRANSCRIPCIO I TRANSLITERACIO DELS NOMS DELS PRINCIPALS VASOS GRECS Joan Alberich i Montserrat Ros ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to give some rules to specialists in order to dis- tinguish between the transliteration of ancient Greek words in the Latin alphabet and their transcription in Catalan. The authors present un alphabetical list of the names of various Greek vases in their original lan- guage, in their transliterated graphy, in their Latin form and in their Ca- talan transcriution. Molt sovint trobem en textos de tota mena mots provinents del grec clhssic grafiats de tal manera que criden l'atenció del lector per la seva forma exbtica i estranya i que, altrament, no reflecteixen amb prou nitidesa la grafia original grega. Generalment, són formes híbrides que responen a una confusió entre el que seria la transliteració i la transcripció d'aquests mots; perb de vegades presenten alteracions més greus per haver seguit rnimbticament i acritica la grafia corresponent en una llengua forastera sense tenir prou en compte ni la llengua de partida, el grec, ni la personali- tat llatina de la llengua d'arribada, el catalh. Per a evitar tals barreges, cal que tinguem una idea ben clara dels criteris diferents que regeixen la trans- literació i la transcripció dels mots. Quan no podem reproduir els mots grecs amb els carhcters originals, o bé no és el nostre interks de fer-ho, i no volem recórrer a la traducció, la transliteració pot ésser un carn' a seguir. L'avantatge principal de la trans- literació és la reducció de les despeses que suposen els canvis tipogrhfics en un mateix text. -

Current Research in Egyptology 2018

Current Research in Egyptology 2018 Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Symposium, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, 25–28 June 2018 edited by Marie Peterková Hlouchová, Dana Belohoubková,v Jirív Honzl, Verav Nováková Access Archaeology eo ha pre rc s A s A y c g c o e l A s o s e A a r h c Archaeopress Publishing Ltd 6XPPHUWRZQ3DYLOLRQ 0LGGOH:D\ 6XPPHUWRZQ 2[IRUG2;/* www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-214-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-215-0 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover photograph: A student of the Czech Institute of Egyptology documenting a decorated limestone stela in the eastern wall of the tomb of Nyankhseshat (AS 104) at Abusir South (photo M. Odler, © Czech Institute of Egyptology) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of paper presentations iii–vii List of poster presentations DQGSURMHFWSUHVHQWDWLRQ viii Introduction ix 7KHFUHZRIWKHVXQEDUNEHIRUHWKHÀUVWDSSHDUDQFHRIWKHAmduat. 1–16 A new perspective via the Pyramid and &RIÀQ7H[WV $EGHOKDOHHP$ZDGDOODK 2. ‘Hail you, Horus jm.j-Cn.wt’?. First thoughts on papyrus Leiden I 347 17–22 6XVDQQH%HFN 3. Some thoughts on Nubians in Gebelein region during 23–41 First Intermediate Period :RMFLHFK(MVPRQG 4. A few remarks on the persistence of native Egyptian KLVWRULRODH 42–54 in Coptic magical texts .ULV]WLQD+HYHVL 5. -

Ä G Y P T I S C H E

Ä g y p t i s c h e Geschichte Ä g y p t e n Ägyptische Genealogie und Geschichte nach Erkenntnis von Gotthard Matysik Pharao Tutanchamun Pharaonen-Thron Nofretete Ägyptologen: Champollion Jean Francois (Franzose), entzifferte 1822 die ägyptischen Hieroglyphen Belzoni (Italiener), der Sammler Lepsius (Deutscher), der Ordner Mariette (Franzose), der Bewahrer Petrie (Engländer), der Messende u. Deuter Schlögl (Schweiz) Historiker der Geschichte Ägyptens: Manetho, ägyptischer Hohepriester in Heliopolis, * in Sebennytos im 3. Jahrhundert v. Chr., Verfasser einer nicht original überlieferten Pharaonengeschichte mit ihrer Einteilung in 30 Dynastien. Diodorus Sicullus, aus Sizilien, griechischer Historiker, 1. Jahrhundert v. Chr., Verfasser einer ägyptischen Geschichte Prf. Kenneth Kitchen (Ägyptologe). Verfasser des „The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt“ von 1973 Dr. David Rohl, Verfasser von „Pharaonen u. Propheten“ u. „Das Alte Testament auf dem Prüfstand“ von 1996 Herrscher in ä g y p t e n Stufenmastaba von König Djoser Felsentempel von Abu Simbel Das Schwarze Land (ägyptisch: Kemet) war der Wohnsitz des Horus, eines lebenden Königs u. seiner göttlichen Mutter Isis. Das Rote Land (ägyptisch: Deschret), die riesige Wüste, das Reich der Gefahr u. des Unheils, regiert von Seth (ägyptisch: Set Sutech), dem Gott des Chaos. Pharao (Titel) = par-o = großes Tor (ähnlich der „hohen Pforte) Vordynastische Periode vor 3200 bis 3150 vor Chr. um 3400 v. Chr. Onyxkopfstandarte Fingerschnecke Fisch Pen-abu um 3300 Elefant Funde könnten seinen Namen tragen, Lesung unsicher. Stier um 3250 Rinderkopfstandarte, vermutl. Kleinkönig von Skorpion I. besiegt. Skorpion I. um 3250 v. Chr. Skorpion I. in Oberägypten. Schrift und Bewässerungsanlagen wurden eingeführt. Grab in Abydos 1988 entdeckt.