Pressure Measurement.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Fluid Statics

CHAPTER 11 | FLUID STATICS 357 11 FLUID STATICS Figure 11.1 The fluid essential to all life has a beauty of its own. It also helps support the weight of this swimmer. (credit: Terren, Wikimedia Commons) Learning Objectives 11.1. What Is a Fluid? • State the common phases of matter. • Explain the physical characteristics of solids, liquids, and gases. • Describe the arrangement of atoms in solids, liquids, and gases. 11.2. Density • Define density. • Calculate the mass of a reservoir from its density. • Compare and contrast the densities of various substances. 11.3. Pressure • Define pressure. • Explain the relationship between pressure and force. • Calculate force given pressure and area. 11.4. Variation of Pressure with Depth in a Fluid • Define pressure in terms of weight. • Explain the variation of pressure with depth in a fluid. • Calculate density given pressure and altitude. 11.5. Pascal’s Principle • Define pressure. • State Pascal’s principle. • Understand applications of Pascal’s principle. • Derive relationships between forces in a hydraulic system. 11.6. Gauge Pressure, Absolute Pressure, and Pressure Measurement • Define gauge pressure and absolute pressure. • Understand the working of aneroid and open-tube barometers. 11.7. Archimedes’ Principle • Define buoyant force. • State Archimedes’ principle. • Understand why objects float or sink. • Understand the relationship between density and Archimedes’ principle. 11.8. Cohesion and Adhesion in Liquids: Surface Tension and Capillary Action • Understand cohesive and adhesive forces. • Define surface tension. • Understand capillary action. 11.9. Pressures in the Body • Explain the concept of pressure the in human body. • Explain systolic and diastolic blood pressures. • Describe pressures in the eye, lungs, spinal column, bladder, and skeletal system. -

Pressure, Its Units of Measure and Pressure References

_______________ White Paper Pressure, Its Units of Measure and Pressure References Viatran Phone: 1‐716‐629‐3800 3829 Forest Parkway Fax: 1‐716‐693‐9162 Suite 500 [email protected] Wheatfield, NY 14120 www.viatran.com This technical note is a summary reference on the nature of pressure, some common units of measure and pressure references. Read this and you won’t have to wait for the movie! PRESSURE Gas and liquid molecules are in constant, random motion called “Brownian” motion. The average speed of these molecules increases with increasing temperature. When a gas or liquid molecule collides with a surface, momentum is imparted into the surface. If the molecule is heavy or moving fast, more momentum is imparted. All of the collisions that occur over a given area combine to result in a force. The force per unit area defines the pressure of the gas or liquid. If we add more gas or liquid to a constant volume, then the number of collisions must increase, and therefore pressure must increase. If the gas inside the chamber is heated, the gas molecules will speed up, impact with more momentum and pressure increases. Pressure and temperature therefore are related (see table at right). The lowest pressure possible in nature occurs when there are no molecules at all. At this point, no collisions exist. This condition is known as a pure vacuum, or the absence of all matter. It is also possible to cool a liquid or gas until all molecular motion ceases. This extremely cold temperature is called “absolute zero”, which is -459.4° F. -

Pressure Measuring Instruments

testo-312-2-3-4-P01 21.08.2012 08:49 Seite 1 We measure it. Pressure measuring instruments For gas and water installers testo 312-2 HPA testo 312-3 testo 312-4 BAR °C www.testo.com testo-312-2-3-4-P02 23.11.2011 14:37 Seite 2 testo 312-2 / testo 312-3 We measure it. Pressure meters for gas and water fitters Use the testo 312-2 fine pressure measuring instrument to testo 312-2 check flue gas draught, differential pressure in the combustion chamber compared with ambient pressure testo 312-2, fine pressure measuring or gas flow pressure with high instrument up to 40/200 hPa, DVGW approval, incl. alarm display, battery and resolution. Fine pressures with a resolution of 0.01 hPa can calibration protocol be measured in the range from 0 to 40 hPa. Part no. 0632 0313 DVGW approval according to TRGI for pressure settings and pressure tests on a gas boiler. • Switchable precision range with a high resolution • Alarm display when user-defined limit values are • Compensation of measurement fluctuations caused by exceeded temperature • Clear display with time The versatile pressure measuring instrument testo 312-3 testo 312-3 supports load and gas-rightness tests on gas and water pipelines up to 6000 hPa (6 bar) quickly and reliably. testo 312-3 versatile pressure meter up to Everything you need to inspect gas and water pipe 300/600 hPa, DVGW approval, incl. alarm display, battery and calibration protocol installations: with the electronic pressure measuring instrument testo 312-3, pressure- and gas-tightness can be tested. -

Surface Tension Measurement." Copyright 2000 CRC Press LLC

David B. Thiessen, et. al.. "Surface Tension Measurement." Copyright 2000 CRC Press LLC. <http://www.engnetbase.com>. Surface Tension Measurement 31.1 Mechanics of Fluid Surfaces 31.2 Standard Methods and Instrumentation Capillary Rise Method • Wilhelmy Plate and du Noüy Ring Methods • Maximum Bubble Pressure Method • Pendant Drop and Sessile Drop Methods • Drop Weight or Volume David B. Thiessen Method • Spinning Drop Method California Institute of Technology 31.3 Specialized Methods Dynamic Surface Tension • Surface Viscoelasticity • Kin F. Man Measurements at Extremes of Temperature and Pressure • California Institute of Technology Interfacial Tension The effect of surface tension is observed in many everyday situations. For example, a slowly leaking faucet drips because the force of surface tension allows the water to cling to it until a sufficient mass of water is accumulated to break free. Surface tension can cause a steel needle to “float” on the surface of water although its density is much higher than that of water. The surface of a liquid can be thought of as having a skin that is under tension. A liquid droplet is somewhat analogous to a balloon filled with air. The elastic skin of the balloon contains the air inside at a slightly higher pressure than the surrounding air. The surface of a liquid droplet likewise contains the liquid in the droplet at a pressure that is slightly higher than ambient. A clean liquid surface, however, is not elastic like a rubber skin. The tension in a piece of rubber increases as it is stretched and will eventually rupture. A clean liquid surface can be expanded indefinitely without changing the surface tension. -

Lecture # 04 Pressure Measurement Techniques and Instrumentation

AerE 344 class notes LectureLecture ## 0404 PressurePressure MeasurementMeasurement TechniquesTechniques andand InstrumentationInstrumentation Hui Hu Department of Aerospace Engineering, Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 50011, U.S.A Copyright © by Dr. Hui Hu @ Iowa State University. All Rights Reserved! MeasurementMeasurement TechniquesTechniques forfor ThermalThermal--FluidsFluids StudiesStudies Velocity, temperature, density (concentration), etc.. • Pitot probe • hotwire, hot film Intrusive • thermocouples techniques • etc ... Thermal-Fluids measurement techniques • Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LDV) particle-based • Planar Doppler Velocimetry (PDV) techniques • Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) • etc… Non-intrusive techniques • Laser Induced Fluorescence (LIF) • Molecular Tagging Velocimetry (MTV) molecule-based • Molecular Tagging Therometry (MTT) techniques • Pressure Sensitive Paint (PSP) • Temperature Sensitive Paint (TSP) • Quantum Dot Imaging • etc … Copyright © by Dr. Hui Hu @ Iowa State University. All Rights Reserved! Pressure measurements • Pressure is defined as the amount of force that presses on a certain area. – The pressure on the surface will increase if you make the force on an area bigger. – Making the area smaller and keeping the force the same also increase the pressure. – Pressure is a scalar F dF P = n = n A dA nˆ dFn dA τˆ Copyright © by Dr. Hui Hu @ Iowa State University. All Rights Reserved! Pressure measurements Pgauge = Pabsolute − Pamb Manometer Copyright © by Dr. Hui Hu @ Iowa State University. All Rights Reserved! -

Pressure Sensor/ Rohs 3-Screen Display Sensor Monitor IP65

Remote Type Pressure Sensor/ RoHS 3-Screen Display Sensor Monitor IP65 Pressure Sensor for General Fluids PSE57२ Series Rated pressure range 0 to 1 MPa −100 to 100 kPa 0 to 500 kPa 0 to 2 MPa 0 to 5 MPa 0 to 10 MPa Withstand voltage 500 VAC <Twice that of the PSE560> Materials of Parts in Contact with Fluid Piping port C3604 + Nickel plating Pressure sensor Al2O3 (Alumina 96%) Square ring FKM NewNew 3-Screen Display Sensor Monitor PSE300AC Series Change the settings while checking the measured value. Visualization of Settings Set value (Threshold value) Main screen Measured value (Current pressure value) Hysteresis value Sub screen Delay time Label (Display item), Set value (Threshold value) Peak value Bottom value PSE57२/PSE300AC Series CAT.ES100-119A Pressure Sensor for General Fluids PSE57२ Series bPSE570/573/574 Materials of parts in bPSE575/576/577 Materials of parts in contact with fl uid contact with fl uid (1 MPa/100 kPa/500 kPa) (2 MPa/5 MPa/10 MPa) Pressure sensor PressurePre sensor O-ring Al2O3 Port size AlA 2O3 (Alumina 96%) FKM + Grease (Alumina 96%) R1/4 (with M5 female thread) Square ring FKM Port size Fitting R1/8, 1/4 Fitting C3604 + (with M5 female thread) C3604 + Nickel plating Nickel plating Series Variations Series Variations Proof Proof Model Rated pressure range pressure Model Rated pressure range pressure −100 kPa 0 100 kPa 500 kPa 1 MPa 2 MPa 5 MPa 10 MPa −100 kPa 0 100 kPa 500 kPa 1 MPa 2 MPa 5 MPa 10 MPa 3.0 5.0 PSE570 PSE575 1 MPa MPa 2 MPa MPa 600 12.5 PSE573 ± PSE576 100 kPa kPa 5 MPa MPa 10 MPa 1.5 30 PSE574 -

Advisory Circular

AC 4302B DATE 10/16/80 ADVISORY CIRCULAR DEPAl<TI\IEST OF TiL4SSPOlCTATiON Federal Aviation Administration Washington, D.C. .Srr bjecrt : MINIMUMMOmY FDR CLIEMTIONAND TEST OFAIMOS~RIC PRESSUPEINSTRUMENTS 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) provides guidance material &ich may be used to determine the adequacy of barometers used in the calibration of aircraft static instruments. It explains barometric accuracy requirements and provides general information pertaining to altitude and atmospheric pressure rneasursnent Additional information concerning the general operation, calibration, and Wntenance of barmeters is presented. 20 CANCEIILATION. AC 43.2A, Minimum Barametry for Calibration and Test of Atmospheric Pressure Instruments, dated August 22, 1974, is cancelled. 3 BACKGROUND.'Ihe Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has long recognized the direct relation that exists between altimeter accuracy and the efficiency with which the available airspace can be utilized. Accurate altimetry contributes to collision avoidance and terrain clearance. To improve safety in this area, the agency adopted rules prescribing periodic tests of aircraft altimeter systems. Following is a general discussion of each of the major areas of barometry &ich concern persons using barameters in aviation. 4 RASIC PEFERENCE. The National Bureau of Standards of the Department of Cknerce published Monograph 8 entitled "kkrcury Barometers and Emcxneters." This excellent publication ms prepared to fill the need of manufacturers and use& of barometers for information &ich was scattered through the literature and, in some cases, ws unpublished. 'Ihe definitions and terminology used in the mnograph will be used in this AC. kbnograph 8 describes the variety of design elements &ich are critical in obtaining precision and accuracy from these instruments. -

Mercury Barometers and Manometers

NBS MONOGRAPH 8 Mercuiy Barometers and Manometers U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS Functions and Activities The functions of the National Bureau of Standards are set forth in the Act of Congress, March 3, 1901, as amended by Congress in Public Law 619, 1950. These include the development and maintenance of the national standards of measurement and the provision of means and methods for making measurements consistent with these standards; the determination of physical constants and properties of materials; the development of methods and instruments for testing materials, devices, and structures; advisory services to government agencies on scientific and technical problems; in- vention and development of devices to serve special needs of the Government; and the development of standard practices, codes, and specifications. The work includes basic and applied research, development, engineering, instrumentation, testing, evaluation, calibration services, and various consultation and information services. Research projects are also performed for other government agencies when the work relates to and supplements the basic program of the Bureau or when the Bureau's unique competence is required. The scope of activities is suggested by the listing of divisions and sections on the inside of the back cover. Publications The results of the Bureau's work take the form of either actual equipment and devices or pub- lished papers. These papers appear either in the Bureau's own series of publications or in the journals of professional and scientific societies. The Bureau itself publishes three periodicals available from the Government Printing Office: The Journal of Research, published in four separate sections, presents complete scientific and technical papers; the Technical News Bulletin presents summary and pre- liminary reports on work in progress; and Basic Radio Propagation Predictions provides data for determining the best frequencies to use for radio communications throughout the world. -

MODULE 11: GLOSSARY and CONVERSIONS Cell Engines

Hydrogen Fuel MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS Cell Engines CONTENTS 11.1 GLOSSARY.......................................................................................................... 11-1 11.2 MEASUREMENT SYSTEMS .................................................................................. 11-31 11.3 CONVERSION TABLE .......................................................................................... 11-33 Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines and Related Technologies: Rev 0, December 2001 Hydrogen Fuel MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS Cell Engines OBJECTIVES This module is for reference only. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines and Related Technologies: Rev 0, December 2001 PAGE 11-1 Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS 11.1 Glossary This glossary covers words, phrases, and acronyms that are used with fuel cell engines and hydrogen fueled vehicles. Some words may have different meanings when used in other contexts. There are variations in the use of periods and capitalization for abbrevia- tions, acronyms and standard measures. The terms in this glossary are pre- sented without periods. ABNORMAL COMBUSTION – Combustion in which knock, pre-ignition, run- on or surface ignition occurs; combustion that does not proceed in the nor- mal way (where the flame front is initiated by the spark and proceeds throughout the combustion chamber smoothly and without detonation). ABSOLUTE PRESSURE – Pressure shown on the pressure gauge plus at- mospheric pressure (psia). At sea level atmospheric pressure is 14.7 psia. Use absolute pressure in compressor calculations and when using the ideal gas law. See also psi and psig. ABSOLUTE TEMPERATURE – Temperature scale with absolute zero as the zero of the scale. In standard, the absolute temperature is the temperature in ºF plus 460, or in metric it is the temperature in ºC plus 273. Absolute zero is referred to as Rankine or r, and in metric as Kelvin or K. -

The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735 – 1745

The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735 – 1745 Jim R. SMITH, United Kingdom Key words: Peru. Meridian. Arc. Triangulation. ABSTRACT: In the early 18th century the earth was recognised as having some ellipsoidal shape rather than a true sphere. Experts differed as to whether the ellipsoid was flattened at the Poles or the Equator. The French Academy of Sciences decided to settle the argument once and for all by sending one expedition to Lapland- as near to the Pole as possible; and another to Peru- as near to the Equator as possible. The result supported the view held by Newton in England rather than that of the Cassinis in Paris. CONTACT Jim R. Smith, Secretary to International Institution for History of Surveying & Measurement 24 Woodbury Ave, Petersfield Hants GU32 2EE UNITED KINGDOM Tel. & fax + 44 1730 262 619 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ddl.org/figtree/hsm/index.htm HS4 Surveying and Mapping the Americas – In the Andes of South America 1/12 Jim R. Smith The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735-1745 FIG XXII International Congress Washington, D.C. USA, April 19-26 2002 THE MERIDIAN ARC MEASUREMENT IN PERU 1735 – 1745 Jim R SMITH, United Kingdom 1. BACKGROUND The story might be said to begin just after the mid 17th century when Jean Richer was sent to Cayenne, S. America, to carry out a range of scientific experiments that included the determination of the length of a seconds pendulum. He returned to Paris convinced that in Cayenne the pendulum needed to be 11 lines (2.8 mm) shorter there than in Paris to keep the same time. -

Crystal Clear

Why Pressure Scales Cause to characterize pressure. There are an incredible variety of pres- Downloaded from So Much Confusion sure scales. Although most of us will not encounter all of these scales except in textbooks, all of us will encounter enough of them Anthony D. Buonaquisti to marvel at technologies' ability to make iife "interesting". University of South Florida The fact is that 1 Torr of gas pressure equals: Pressure scales can be extremely confusing to new op- 1333 dyne per square centimeter https://www.cambridge.org/core erators. This is not surprising. To my mind, there are three pri- 1333 microbar mary areas of confusion. 1333 Bayre Firstly, the pressure of gas inside an instrument changes 1000 microns of mercury over many orders of magnitude during pump-down. The 133.3 Newton per square meter change is about 9 orders of magnitude for a traditional Scan- 1333333 Geede ning Electron Microscope and about 13 orders of magnitude for 13.59 millimeters of water an ultra-high vacuum instrument such as a Scanning Auger 13,59 kilograms per square meter Microprobe. 1.33 millibar . IP address: To give an idea about the scale of change involved in vac- 1.35 centimeters of water uum, consider that the change in going from ambient pressure 1.35 Guericke to that inside a typical ultra high vacuum system is like compar- 0.0393 inches of mercury 170.106.33.19 ing one meter with the mean radius of the planet Pluto's orbit. 0.0193 pounds per square inch The fact is that we don't often get to play with things on that 0.1333 Pieze scale. -

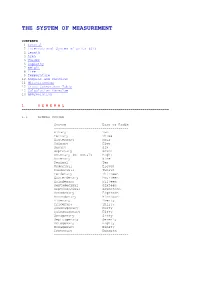

The System of Measurement

THE SYSTEM OF MEASUREMENT CONTENTS 1 General 2 International System of Units (SI) 3 Length 4 Area 5 Volume 6 Capacity 7 Weight 8 Time 9 Temperature 10 Angular and Circular 11 Miscellaneous 12 Cross Conversion Table 13 Calculation Formulae 14 Abbreviation 1. G E N E R A L ========================================================================= 1.1 NUMBER SYSTEM ------------------------------------- System Base of Radix ------------------------------------- Binary Two Ternary Three Quaternary Four Quinary Five Senary Six Septenary Seven Octonary (or Octal) Eight Novenary Nine Decimal Ten Undecimal Eleven Duodecimal Twelve Terdenary Thirteen Quaterdenary Fourteen Quindenary Fifteen Sextodecimal Sixteen Septendecimal Seventeen Octodenary Eighteen Novendenary Nineteen Vicenary Twenty Tricenary Thirty Quadragenary Forty Quinquagenary Fifty Sexagenary Sixty Septuagenary Seventy Octogenary Eighty Nonagenary Ninety Centenary Hundred ------------------------------------- 1.2 STANDARD SYSTEM OF SCIENTIFIC NOTATION (DECIMAL SYSTEM OR PREFIXES SYSTEM) ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----- Prefix Symbol Value Submultiples and Multiples ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----- atto (at' to) a .000 000 000 000 000 001 1x10- 18 femto (fem' to) f .000 000 000 000 001 1x10- 15 pico (pe' ko) p .000 000 000 001 one-millionth millionth 1x10- 12 nano (nan' o) n .000 000 001 1000 of a millionth 1x10-9 micro (mi' kro) u* .000 001 one-millionth 1x10-6 milli (mil' i) m* .001 one-thousandth 1x10-3 centi (sen' ti) c* .01 one-hundredth 1x10-2 deci (des' i) d .1 one-tenth 1x10-1 deca (dek' a) da 10 ten 1x101 hecto (hek' to) h 100 one hundred 1x102 kilo (kil' o) k* 1 000 one thousand 1x103 mega (meg' a) M* 1 000 000 one million 1x106 giga (ji' ga) G 1 000 000 000 one thousand million 1x109 tera (ter' a) T 1 000 000 000 000 one-million million 1x1012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- * Most commonly used.