English Restoration Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19584-3 - Thomas Betterton: The Greatest Actor of the Restoration Stage David Roberts Frontmatter More information THOMAS BETTERTON Restoration London’s leading actor and theatre manager Thomas Betterton has not been the subject of a biography since 1891. He worked with all the best-known playwrights of his age and with the first generation of English actresses; he was intimately involved in the theatre’s responses to politics, and became a friend of leading literary men such as Pope and Steele. His innovations in scenery and company management, and his association with the dramatic inher- itance of Shakespeare, helped to change the culture of English thea- tre. David Roberts’s entertaining study unearths new documents and draws fresh conclusions about this major but shadowy figure. It con- textualises key performances and examines Betterton’s relationship to patrons, colleagues and family, as well as to significant historical moments and artefacts. The most substantial study available of any seventeenth-century actor, Thomas Betterton gives one of England’s greatest performing artists his due on the tercentenary of his death. dav id roberts is Professor and Head of English at Birmingham City University. His previous publications include The Ladies: Female Patronage of Restoration Drama (1989) and editions of Defoe’s Colonel Jack, A Journal of the Plague Year and Lord Chesterfield’s letters. His articles and reviews have appeared in leading journals including Shakespeare Quarterly, The Review of English Studies, ELH, The Times Literary Supplement and New Theatre Quarterly. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19584-3 - Thomas Betterton: The Greatest Actor of the Restoration Stage David Roberts Frontmatter More information Letter from Thomas Betterton to Colonel Finch, steward to Thomas Thynne, Lord Weymouth, in Longleat House, Thynne Papers, vol. -

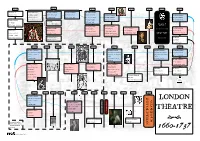

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

6 X 10.Long New.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-71397-9 - How to Read a Shakespearean Play Text Eugene Giddens Index More information Index accidental, 32, 44, 47, 100, 101, 116, 144 Brown, Arthur, 105, 149 act and scene divisions, 77–80 Brown, John Russell, 148, 150 advertisements, 12, 97 Buc, Sir George, 17 Alcorn, Thomas, 35 Burbage, Richard, 27 Allde, Edward, 40, 134 Burre, Walter, 61 Arden Shakespeare, 4, 50, 102, 112, 117, 149, 154, Burt, Richard, 13, 18 159, 160, 161, 164, 165, 167 Butter, Nathaniel, 62 arguments, 75 Armin, Robert, 27 Cambises, 72 Aspley, William, 27, 61, 97 Cambridge School Shakespeare, 167 Cambridge University Library, 143 bad quartos, 23–5, 49 Campion, Thomas Barton, Anne, 163 Masque at Lord Hay’s Marriage, 72 Bate, Jonathan, 109, 112, 154, 163, 167 Capell, Edward, 161 Beaumont, Francis, 9, 12, 18, 23, 33, 35, 39, 41, capitalisation, 81, 85, 88, 93, 107, 140 66, 69, 147, 150, 152 Carson, Christie, 171 Beaumont, Francis and John Fletcher Carson, Neil, 8, 9, 10, 35 Wild Goose Chase, 18 casting off, 41, 42, 89, 90, 133, 134 Beaumont, Francis, John Fletcher, and Philip catchwords, 96, 124–5, 151 Massinger chainlines, 137–8 Beggar’s Bush, 62 Chamberlain’s Men, 27, 29, 58 Benson, John, 19 Chapman, George, 9, 65 Berger, Thomas L., 160 Chettle, Henry, 14, 18 Bertram, Paul, 102 Clare, Janet, 16, 17 Best, Michael, 170 collation, 121–3 beta radiography, 135 collation line, 151, 160–4 Bevington, David, 81, 151, 158, 162, 164 collation, stop-press correction, 142–5 Blackfriars Theatre, 27 colophons, 97 black-letter, 86 composing stick, 43, 133 Blayney, Peter W. -

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: the Survival of the London Theatre Community

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: The Survival of the London Theatre Community By Mary Alex Staude Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: (Signature of Advisor) Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reid Barbour for his support, guidance, and advice throughout this process. Without his help, this project would not be what it is today. Thanks also to Laura Pates, Adam Maxfield, Alex LaGrand, Aubrey Snowden, Paul Smith, and Playmakers Repertory Company. Also to Diane Naylor at Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Much love to friends and family for encouraging my excitement about this project. Particular thanks to Nell Ovitt for her gracious enthusiasm, and to Hannah Dent for her unyielding support. I am grateful for the community around me and for the communities that came before my time. Preface Mary Alex Staude worked on Twelfth Night 2017 with Alex LaGrand who worked on King Lear 2016 with Zack Powell who worked on Henry IV Part II 2015 with John Ahlin who worked on Macbeth 2000 with Jerry Hands who worked on Much Ado About Nothing 1984 with Derek Jacobi who worked on Othello 1964 with Laurence Olivier who worked on Romeo and Juliet 1935 with Edith Evans who worked on The Merry Wives of Windsor 1918 with Ellen Terry who worked on The Winter’s Tale 1856 with Charles Kean who worked on Richard III 1776 with David Garrick who worked on Hamlet 1747 with Charles Macklin who worked on Henry IV 1738 with Colley Cibber who worked on Julius Caesar 1707 with Thomas Betterton who worked on Hamlet 1661 with William Davenant who worked on Henry VIII 1637 with John Lowin who worked on Henry VIII 1613 with John Heminges who worked on Hamlet 1603 with William Shakespeare. -

“A Poor Player That Struts and Frets His Hour Upon the Stage…”

“A POOR PLAYER THAT STRUTS AND FRETS HIS HOUR UPON THE STAGE…” THE ENGLISH THEATRE IN TRANSITION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Christin N. Gambill May, 2016 “A POOR PLAYER THAT STRUTS AND FRETS HIS HOUR UPON THE STAGE…” THE ENGLISH THEATRE IN TRANSITION Christin N. Gambill Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mr. James Slowiak Dr. John Green _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Adel Migid Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Date Dr. Hillary Nunn _______________________________ School Director Dr. J. Thomas Dukes ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. “THIS ROYAL THRONE THIS SCEPTERED ISLE…” THE THEATRE OF THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE COMING STORM .............................................................................................. 14 III. THE AXE FALLS ...................................................................................................... 29 IV. UNDER THEIR NOSES ............................................................................................ 42 V. THE NEW ORDER ..................................................................................................... 53 VI. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS -

A Critical Edition of John Fletcher's Comedy: Monsieur Thomas Or

Routledge Revivals A Critical Edition of John Fletcher’s Comedy A Critical Edition of John Fletcher’s Comedy Monsieur Thomas or Father’s Own Son Edited by Nanette Cleri Clinch The Renaissance Imagination Volume 25 First published in 1987 by Garland Publishing, Inc. This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 1987 by Taylor & Francis All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. Disclaimer The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact. A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: ISBN 13: 978-0-367-19172-6 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-429-20088-5 (ebk) The Renaissance Imagination Important Literary and Theatrical Texts from the Late Middle Ages through the Seventeenth Century Stephen Orgel E ditor Volumes in the Series 1. Arte of Rhetorique by Thomas 8. Greene's Tu Quoque Or, The Cittie Wilson Gallant byj. Cooke edited by Thomas J. Derrick A critical edition 2. -

Sarah Siddons As Lady Macbeth / Patricia T

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1974 Sarah Siddons as Lady Macbeth / Patricia T. Michael Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Michael, Patricia T., "Sarah Siddons as Lady Macbeth /" (1974). Theses and Dissertations. 4414. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/4414 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SA.RAH SIDDONS AS LADY MACBETH by Patricia T. Michael A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Lehigh University 1974 This thesis 1s accepted and approved in partial ru1- f111rncnt of tl1e requirements for the degree of ?-1aster of Arts. ~,} / g. H Chairman o , ii \ AC KNOW LEDGMEN'I' The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the contstant advice and assistance of Professor Fraink S. Hook, who I deeply respect for his wisdom and knowledge, and admire for his patience and understanding. • • • lll ,A' Table of Contento Page 11 Certificate of Approval . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 111 Acknowledgment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • iv Table of Contents . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Abstract • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Chapter I: Before Sarah Siddons • • • • • • • • • • 11 Chapter II: Mrs. Siddons on Stage • • • • • • • • • • 28 Act I. Sc. V • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 34 Act I. Sc. vi • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Act I. Sc. Vll • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 35 38 Act II. Sc. ii • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4:J- Act III. Sc. ll • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 48 Act III. Sc. lV • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 45 Act V. -

Performing Multilingualism on the Caroline Stage in the Plays of Richard Brome

Performing Multilingualism on the Caroline Stage in the Plays of Richard Brome Performing Multilingualism on the Caroline Stage in the Plays of Richard Brome By Cristina Paravano Performing Multilingualism on the Caroline Stage in the Plays of Richard Brome By Cristina Paravano This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Cristina Paravano All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0593-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0593-3 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................... vii Quotations, Abbreviations and Conventions .............................................. ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Through the Prism of Multilingualism Chapter One ............................................................................................... 19 ‟There’s too much French in town”: The New Academy and The Demoiselle Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 37 ‟Simile non est idem”: The City Wit and -

A Dramaturgical Study of Merrythought's Songs in the Knight

Early Theatre 12.2 (2009) Katrine K. Wong A Dramaturgical Study of Merrythought’s Songs in The Knight of the Burning Pestle ‘Let him stay at home and sing for his dinner’, advises Mistress Merrythought about her highly musical husband, Old Merrythought, who believes in achiev- ing mirth and health through much singing, a good portion of which has the pretext of conviviality, in particular, drinking.1 The philosophy embedded in Old Merrythought’s sundry songs in Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (c 1607)2 shows the coexistence of orderliness and disor- derliness related to music, a duality pervasive in the use of music in English Renaissance drama. Early modern English culture attached a wide range of associations to music; various pairs of ideological dichotomies can be identi- fied, such as sublimation and corruption of the soul, love and lust, masculin- ity and femininity, and destruction and restoration of sanity.3 In this essay, I first provide a brief contextual background of the perception and practice of music, and illustrate with a few episodes from Elizabethan and Jacobean plays the diversity of connotations carried by music as well as how music can be incorporated into various types of dramatic scenarios.4 These examples reflect the general musical landscape of Renaissance drama. I then evaluate the dramaturgical characteristics of Merrythought’s songs in relation to the contemporary cultural and dramatic milieux. Views on Music The negotiation between the divine and the corrupting in music has always been an important part of the social and philosophical understanding of the art since classical times. -

Cambridge Companion Eng Renais Drama

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama This second edition of the Companion offers students up-to-date factual and interpretative material about the principal theatres, playwrights, and plays of the most important period of English drama, from 1580 to 1642. Three wide- ranging chapters on theatres, dramaturgy, and the social, cultural, and political conditions of the drama are followed by chapters describing and illustrating various theatrical genres: private and occasional drama, political plays, heroic plays, burlesque, comedy, tragedy, with a final essay on the drama produced during the reign of Charles I. Several of the essays have been substantially revised and all of the references updated. An expanded biographical and bib- liographical section details the work of the dramatists discussed in the book and the best sources for further study. A chronological table provides a full listing of new plays performed from 1497 to 1642, with a parallel list of major political and theatrical events. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DRAMA EDITED BY A. R. BRAUNMULLER AND MICHAEL HATTAWAY SECOND EDITION cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521821155 © Cambridge University Press 1990, 2003 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.