In This Week's Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

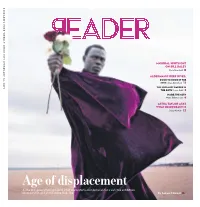

Age of Displacement As the U.S

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | FEBRUARY | FEBRUARY CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Mayoral Spotlight on Bill Daley Nate Marshall 11 Aldermanic deep dives: DOOR TO DOOR IN THE 25TH Anya Davidson 12 THE SOCIALIST RAPPER IN THE 40TH Leor Galil 8 INSIDE THE 46TH Maya Dukmasova 6 Astra Taylor asks what democracy is Sujay Kumar 22 Age of displacement As the U.S. government grinds to a halt and restarts over demands for a wall, two exhibitions examine what global citizenship looks like. By SC16 THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | FEBRUARY | VOLUME NUMBER TR - A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR @ HAPPYVALENTINE’SDAY! To celebrate our love for you, we got you a LOT lot! FOUR. TEEN. LA—all of it—only has 15 seats on its entire city council. PTB of stories about aldermanic campaigns. Our election coverage has been Oh and it’s so anticlimactic: in a couple weeks we’ll dutifully head to the ECAEM so much fun that even our die-hard music sta ers want in on it. Along- polls to choose between them to determine who . we’ll vote for in the ME PSK side Maya Dukmasova’s look at the 46th Ward, we’re excited to present runo in April. But more on that next week. ME DKH D EKS Leor Galil’s look at the rapper-turned-socialist challenger to alderman Also in our last issue, there were a few misstatements of fact. Ben C LSK Pat O’Connor in the 40th—plus a three-page comics journalism feature Sachs’s review of Image Book misidentifi ed the referent of the title of D P JR CEAL from Anya Davidson on what’s going down in the 25th Ward that isn’t an part three. -

Recorder.Hu Gerendai Károly Facebook.Com/Recorder.Hu C

terjesztési pontjainkon: ingyenes. előfizetőinknek: 789 Ft. zene fashion zene tech zene media zene design zene business zene art zene digital zene live rec 053 2017 / 06 ALBÁNIA NYÁRI SLÁGEREK ALT-J EURÓPAI FESZTIVÁLOK JLIN POP A 2010-ES ÉVEkbEN SLOWDIVE víz & zene RIDE FOO FIGHTERS RUFUS WAINWRIGHT CALVIN FLEET FOXES ThIEVERY CORPORATION GERENDAI KÁROLY HARRIS. www.recorder.hu facebook.com/recorder.hu C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Recorder_200x270.indd 1 2017. 06. 16. 16:43 tartalom 6 12 14 10 16 www.recorder.hu rec 053 facebook.com/recorder.hu 2017 / 06 lemeztáska 14 A 2017-es nyár slágeresélyei. interjú 4 Eric Hilton (Thievery Corporation). 16 Szörföző zenészek. 28 Slowdive. fesztivál what the faq 30 Ride. 6 Európai fesztiválok. 18 Gerendai Károly. 32 Rufus Wainwright. trend trend profül 8 PWR BTTM: különválasztható-e 20 Hazai promóterek 2. 42 Gyulai István az alt-J-ről. az alkotás az alkotótól? világrecorder recorder 10 Dobozban maradt lemezek. 22 Albánia rejtett csodái. 44 Lemezkritikák. víz & zene front programajánló 12 Magyar előadók kedvenc 24 Calvin Harris és a 2010-es évek 48 Június-júliusi koncertek vízparti dalai. popzenéje. és partik. RECORDER • Ingyenes zenemagazin • REC053: 2017. június www.recorder.hu • www.facebook.com/recorder.hu • www.twitter.com/recorderhu • [email protected] Kiadó: Recorder Kft. • Felelős kiadó: a Kft. ügyvezetője. • ISSN: 2062-9656 • Postacím: 1277 Budapest, Pf. 106 Főszerkesztő: Dömötör Endre • Szerkesztő: Forrai Krisztián • Szerzők: Biczó Andrea, Csada Gergely, Csúri András, Elekes Roland, Fábián Titusz, Gyulai István, Judák Bence, Kollár Bálint, Lékó Tamás, Mika László, Németh Róbert, Reszegi László, Rónai András, Salamon Csaba, Szabó Benedek, Szabó Sz. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Third Coast Percussion Sean Connors Robert Dillon Peter Martin David Skidmore

4045 N Rockwell St [email protected] Chicago, IL 60618 248-909-4075 Third Coast Percussion Sean Connors Robert Dillon Peter Martin David Skidmore PROGRAM INFORMATION FOR “Perspectives” Updated 9/8/20 PROGRAM ORDER “The Hero” from Archetypes (2019/2020) Clarice Assad (b. 1978)/ arr. Third Coast Percussion Perfectly Voiceless (2018) Devonté Hynes (b. 1985) Death Wish (2017) Gemma Peacocke (b. 1984) Perpetulum, movement 3 (2018) Philip Glass (b. 1937) Aphasia (2010) Mark Applebaum (b. 1967) Perspective (2020) Jlin (b. 1987) Paradigm Obscure Derivative Duality Embryo 4045 N Rockwell St [email protected] Chicago, IL 60618 248-909-4075 PROGRAM NOTES A powerful communicator renowned for her musical scope and versatility, Brazilian American Clarice Assad is a significant artistic voice in the classical, world music, pop, and jazz genres, renowned for her evocative colors, rich textures, and diverse stylistic range. A prolific Grammy-nominated composer, with over 70 works to her credit, she is also a celebrated pianist and inventive vocalist. Ms. Assad has released seven solo albums and appeared on—or had her works performed on—another 30. Her award-winning Voxploration Series on music education, creation, songwriting and improvisation has been presented throughout the United States, Brazil, Europe, and the Middle East. Third Coast Percussion worked together with Clarice and her father, the legendary classical guitarist Sérgio Assad, to develop the Archetypes project, which premiered in early 2020. The twelve movements of this suite are each inspired by a universal character concept that appears in stories and myths across cultures, such as the jester, the ruler, the creator, or the caregiver. -

Jlin, Donnacha Costello, M.E.S.H., HKE, David Cordero and Soul Jazz Records Sound System, Are the first Artists Confirmed for Lapsus Festival 2016

! Jlin, Donnacha Costello, M.E.S.H., HKE, David Cordero and Soul Jazz Records Sound System, are the first artists confirmed for Lapsus Festival 2016. • The decision to extend both the space and time schedule are major pieces of news for the event that after the "sold out" 2015 edition, has established itself as a must for lovers of avant-garde electronic music. Barcelona 05/02/16 - Lapsus Festival returns to the CCCB following the success of the last event, in which the organizers had to put up a makeshift "sold out" sign within minutes of opening the doors. And the festival continues to expand both its schedule and location. More than 12 hours of uninterrupted music will begin at noon and end at dawn in the three locations where the festival will be held from now on: added to the already known CCCB Theatre are the Pati de les Dones, which will welcome the first festival goers, and the legendary Hall of the CCCB, which will house those acts best suited to the dance floor. The festival, which will take place on April 2, 2016, will feature, among others, the following live performances: Jlin [USA] Planet Mu The American producer Jlin is undoubtedly the major revelation of the season. A woman in a man's world, such as footwork, who has managed to redesign the foundations of the genre with her first LP "Dark Energy" (Planet Mu, 2015). An album that has been praised as "Record of the Year" by prestigious publications worldwide such as The Wire and The Quietus thanks to its technical excellence, sense and sensibility. -

Turmoil Third Wave of Confirmed Acts and Projects

PRESS RELEASE 12 December 2017 CTM FESTIVAL 2018 – TURMOIL THIRD WAVE OF CONFIRMED ACTS AND PROJECTS FESTIVAL FOR ADVENTUROUS MUSIC & ART, BERLIN 19th EDITION, 26 JANUARY – 4 FEBRUARY 2018 A division of DISK / CTM – Baurhenn, Rohlf, Schuurbiers GbR • Veteranenstraße 21, 10119 Berlin, Germany | 1 | Tax Number 34/496/01492 • International VAT Number DE813561158 Bank Account: Berliner Sparkasse • BLZ: 10050000 • KTO: 636 24 508 • IBAN: De42 1005 0000 0063 6245 08 • BIC: BE LA DE BE THIRD WAVE OF CONFIRMED ARTISTS AND PROJECTS CTM 2018 will run 26 January – 4 February 2018 at Berlin venues HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berghain, YAAM, Festsaal Kreuzberg, SchwuZ, Club OST, and Kunstquartier Bethanien. This 19th edition’s Turmoil theme explores the state of music and sound practice in the face of a confusing and critical present. With programme highlights ranging from a special emphasis on the intersection of music and dance, an exploration of the different threads of gabber and hardcore including pioneering and newer sounds, a special thread exploring the potentials and consequences of rapid advances in machine learning and AI, and a range of artists exploring Turmoil through confrontation, careful scrutiny, or meditation, CTM 2018 continues its inquiry into the potential of sound and music to invigorate our resilience, awareness, and sense of community. Newly-confirmed CTM 2018 acts are: AGF [DE/FI] / Bamba Pana & Makavelli (Sounds of Sisso) [TZ] / Bliss Signal [UK] / Borusiade [RO/DE] / Celestial Trax [US] / Colleen [FR] / “Daemmerlicht” presented by Recondite [DE] / Dengue Dengue Dengue [PE] / DJ Occult [US/DE] / Drew McDowall presents “Time Machines” [UK] / Elena Colombi [UK] / Esa Williams [ZA] / Equiknoxx ft. -

PROGRAM Concert 2

p r e s e n t s Thank you for coming! Please join us at CCRMA on the Stage for the next Winter Concerts: SHARKIFACE | DANISHTA RIVERO Saturday, February 16, 7:30 PM − · − · − · − · · − · − − · − DAVID BEHRMAN: Interactive Situations Thursday, February 21, 7:30 PM − · − · − · − · · − · − − · − MARCO FUSI: Works by Stanford Composers Friday, March 8, 7:30 PM − · − · − · − · · − · − − · − THOMAS BUCKNER: Songs Without Words I M A Thursday, March 14, 7:30 PM − · − · − · − · · − · − − · − LINUX AUDIO CONFERENCE 2019 CONCERTS Saturday, March 23, 6 PM & 8 PM Sunday, March 24, 6 PM & 8 PM Monday, March 25, 8 PM − · − · − · − · · − · − − · − AMNON WOLMAN: Barrier, Stop for inspection Wednesday, March 27, 7:30 PM CONCERT 2 If you would like to stay up to date with our events, Bing Concert Hall please subscribe to our mailing list: http://ccrma-mail.stanford.edu/mailman/listinfo/events Saturday, February 2, 2019 7:30 PM of sound while building his own analog synthesizers a very very long time ago, and even after more than 30 years, “El Dinosaurio” is still being used PROGRAM in live performances. He was the Edgar Varese Guest Professor at TU Berlin during the Summer of 2008. In 2014 he received the Marsh O’Neill Award Sk(etch) (2018) Leah Reid For Exceptional and Enduring Support of Stanford University’s Research 7.1 channels diffused in Ambisonics Enterprise. Shifting Soundscapes (2018) Kevin Su Jessie Marino is a composer/performer/media artist from Long Island, New 5.1 channels diffused in Ambisonics York. Her current work explores the virtuosity of common activities, ritualistic absurdity, and the archeology of recent media. -

In This Issue

Volume 60, No. 2 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” February 12, 2020 In This Issue... Dems Budget Woes TARTA % Page 2 Page 6 &'(( ' Tolliver Page 3 )* Page 7 Page 10 U Cover Story Cooperative !"# %+ ` Page 5 Page 8 Page 13 Page 15 Page 16 Page 2 S February 12, 2020 Kaptur Statement on President Trump’s FY2021 Budget Request Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur (OH-09), Chair of the House Appro- lion dollars. It also slashes projects that make healthcare more affordable, priations Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, released the strengthen public education, improve access to affordable housing, pro- following statement on President Trump’s Fiscal Year 2021 budget re- tect our Great Lakes, invest in our infrastructure, and help low-income quest: Americans heat their homes in the winter. All of this while proposing a P\] full repeal of the Affordable Care Act, billions more for the ill-conceived our values,” said Rep. Kaptur. “Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, Presi- border wall, and a 10-year extension of his disastrous Tax Cuts and Jobs dent Trump’s FY2021 budget request was not written with working peo- Act, his unprecedented bailout for corporations and the wealthy.” ple in mind – instead, it is a laundry list of conservative priorities and “As Chairwoman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Ener- corporate handouts that literally leave working people in the cold.” gy and Water Development, I will work to ensure that President Trump’s “The President’s budget request calls for massive cuts to vital domes- outlandish requests -

Dissabte 2 D'abril Del 2016. CCCB Barcelona

LAPSUS FESTIVAL Dissabte 2 d’abril del 2016. CCCB Barcelona. www.lapsusfestival.cat QUÈ ÉS LAPSUS? LAPSUS FESTIVAL 2016 Lapsus és una plataforma artística multidisci- Torna Lapsus Festival al CCCB després de l’èxit de plinària en actiu des de 2004 que ha consolidat la darrera edició -els organitzadors van haver de tres àrees d’activitat complementàries: LAPSUS penjar un improvisat cartell de “sold out” pocs RÀDIO, el programa setmanal de LAPSUS a Radio minuts després d’haver obert les portes- i ho fa 3 (RTVE); el segell discogràfic LAPSUS RECORDS, ampliant horaris i espais. Més de 12 hores ininte- amb llançaments trimestrals i distribució interna- rrompudes de música que començaran al migdia i cional via Cargo, la major distribuïdora indepen- que acabaran de matinada als tres escenaris amb dent del món; i LAPSUS FESTIVAL, que es celebra els que comptarà el festival a partir d’ara: al ja anualment al Centre de Cultura Contemporània conegut Teatre del CCCB, se li afegeixen el Pati de de Barcelona (CCCB). les Dones, que donarà la benvinguda als primers assistents del festival, i el mític Hall delCCCB, on Gràcies a aquesta diversificació de la nostra ac- es desenvoluparan les propostes més enfoca- tivitat, la creació de contingut és constant des a la pista. durant tot l’any i és canalitzada en funció de la freqüència d’aparició, del for- La tercera edició del Festival de Mú- mat i de la plataforma utilitzada. siques Electròniques d’Avantguarda Una curosa selecció permanent de LAPSUS FESTIVAL esdevindrà el proper dia continguts que compta amb el recolzament d’un 2 d’abril de 2016 i comptarà amb els següents equipo professional de comunicació, fotografia i artistes convidats: vídeo que proporciona una estudiada presència a xarxes socials i a mitjans de comunicació tradicio- nals amb la corresponent fidelització del nostre públic objectiu, tot consolidant la marca “Lapsus” com a vehicle de continguts de qualitat. -

ENTER STAGE LEFT Actress Returns to Ninja Tune with More Leftfield Magic on ‘AZD’

MUSIC HOT SELECTIONS This month’s essential tracks p.116 BY THE BUCKETLOAD May’s albums unpacked p.136 ON THE MIX ‘N’ BLEND Compilations not to miss this month p.140 ENTER STAGE LEFT Actress returns to Ninja Tune with more leftfield magic on ‘AZD’... p.138 djmag.com 115 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Raam Raam006 [email protected] Raam 8.5 Ooozing class, this sixth release on Swedish producer Raam's own label is a corker. 'Tilted' keeps it understated, while deep, dub-disco 'Const' is a slo-mo delight, topped off with a remix from Qnete. Art Alfie KRLVK9 Karlovak 8.0 Weirdly, this is Art Alfie's first solo EP on his own Karlovak label. 'Trippfiguren' is the killer; MONEY a building, minimal chugger. But it's all pretty SHOT! good, to be fair. Dijon feat. Charles McCloud Ross From Friends Personal Slave Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes Classic Music Company Lobster Theremin 7.0 9.5 Murky, mucky business from Classic veteran T Williams & James four tracks of supremely wonky Likely to be one of the stand- Honey Dijon and her chum Charles McCloud, this Jacob house music for the excellent out house releases of 2017, acidic bombshell is for the freaks on those late- Together EP and equally Peckham-centric this scorching four-tracker night, low-ceiling dancefloors. Aces. Madhouse Rhythm Section. 'Repeater' sees South London's Ross 8.0 couples metallic percussion From Friends having climbed El Prevost b2b Doorly Solid dancefloor gear from T with some lo-fi thumb piano to dizzying heights over the EP1 Williams and James Jacob for vibes, while 'HTRTWr' (nope, us space of just a handful of Reptile Dysfunction Kerri Chandler's Madhouse neither) drones and wheezes, EPs. -

Introduction to Decolonial Thinking and Decolonising Methodologies Seminar Sommersemester 2018 MA Medienkulturanalyse Heinrich-Heine Universität Düsseldorf

Dr. Pedro Oliveira \\\\\_____///// Gebäude 24.21, Raum 00.85 Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter /////_____\\\\\ [email protected] ________________ Introduction to Decolonial thinking and decolonising methodologies Seminar Sommersemester 2018 MA Medienkulturanalyse Heinrich-Heine Universität Düsseldorf Wann: Mittwochs von 12:30 bis 14 Uhr Wo: Raum 2303.01.63 (Z 46) E-mail: pedro.oliveira [at] hhu.de Hinweis: diese Veranstaltung findet in Englischer Sprache statt! Aufgaben dürfen aber auf Deutsch geschrieben bzw. präsentiert werden. In this course we will attempt to re-frame our research apparatuses by looking beyond the canon of Eurocentric research methodologies in the humanities. The wider field of post- and de-colonial studies offers us an opportunity to understand the assets of research and proposes a re-historicising of them towards a non-colonial, non-eurocentric research standpoint. Hence throughout the semester we will revisit key authors on the deconstruction of colonial apparatuses and their influence on research methods, and will also explore key ideas and concepts in decolonising research. The course will be mostly focused on the concept of the “colonial matrix of power” — a framework developed mainly by Latin American decolonial theorists — but will expand and present students to different schools of thought within decolonial thinking from the Global South, as well as with propositions for research methods stemming from Indigenous thought. Offered as a provocative reflection on research methodologies in and for Cultural Studies, this will not provide students with new “research toolkits” or closed frameworks, but rather will encourage the development of a critical standpoint towards undertaking research in a European context within an increasingly decolonising world. -

May 22, 2017 Price $8.99

PRICE $8.99 MAY 22, 2017 MAY 22, 2017 5 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 27 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Jeffrey Toobin on the G.O.P.’s silence; the psychiatry of Trump; advice from a boxer; being yoga; dial-a-feminist playwriting. ONWARD AND UPWARD WITH THE ARTS Fred Kaplan 34 Kind of New Cécile McLorin Salvant rethinks jazz. SHOUTS & MURMURS Susanna Fogel 39 Your Frozen Egg Has a Question ANNALS OF EDUCATION Jonathan Blitzer 40 American Studies Undocumented students’ efforts to get into college. A REPORTER AT LARGE Ian Parker 46 Are You My Mother? A custody case and the definition of parenthood. PROFILES Rebecca Mead 60 The Book Monk A master printer’s lifework. COMIC STRIP Edward Steed 65 “Mets Injury Schedule 2017” FICTION Samantha Hunt 70 “A Love Story” THE CRITICS ON TELEVISION Emily Nussbaum 78 “The Handmaid’s Tale.” LIFE AND LETTERS Thomas Mallon 81 J.F.K. at one hundred. BOOKS 84 Briefly Noted Laura Miller 88 Kei Miller’s “Augustown.” MUSICAL EVENTS Alex Ross 90 Two new concert halls in Germany. POP MUSIC Hua Hsu 92 Jlin’s “Black Origami.” POEMS Carrie Fountain 54 “Poem Without an Image” Stephen Burt 72 “Lamb’s Ear” COVER Barry Blitt “Ejected” DRAWINGS Jason Adam Katzenstein, Jason Patterson, Will McPhail, J. C. Duffy, Emily Flake, P. S. Mueller, Amy Hwang, Drew Dernavich, Bruce Eric Kaplan, David Sipress, Roz Chast, Alice Cheng, John O’Brien, Charlie Hankin, Amy Kurzweil SPOTS Hanna Barczyk CONTRIBUTORS Ian Parker (“Are You My Mother?,” p. 46) Rebecca Mead (“The Book Monk,” p. 60) has contributed to the magazine since has been a staff writer since 1997.