In the Wake of L'esule Di Roma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donizetti Operas and Revisions

GAETANO DONIZETTI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Il Pigmalione (1816), libretto adapted from A. S. Sografi First performed: Believed not to have been performed until October 13, 1960 at Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. • L'ira d'Achille (1817), scenes from a libretto, possibly by Romani, originally done for an opera by Nicolini. First performed: Possibly at Bologna where he was studying. First modern performance in Bergamo, 1998. • Enrico di Borgogna (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: November 14, 1818 at Teatro San Luca, Venice. • Una follia (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: December 15, 1818 at Teatro San Luca,Venice. • Le nozze in villa (1819), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: During Carnival 1820-21 at Teatro Vecchio, Mantua. • Il falegname di Livonia (also known as Pietro, il grande, tsar delle Russie) (1819), libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini First performed: December 26, 1819 at the Teatro San Samuele, Venice. • Zoraida di Granata (1822), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: January 28, 1822 at the Teatro Argentina, Rome. • La zingara (1822), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: May 12, 1822 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. • La lettera anonima (1822), libretto by Giulio Genoino First performed: June 29, 1822 at the Teatro del Fondo, Naples. • Chiara e Serafina (also known as I pirati) (1822), libretto by Felice Romani First performed: October 26, 1822 at La Scala, Milan. • Alfredo il grande (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: July 2, 1823 at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples. • Il fortunate inganno (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: September 3, 1823 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. -

La Favorite Opéra De Gaetano Donizetti

La Favorite opéra de Gaetano Donizetti NOUVELLE PRODUCTION 7, 9, 12, 14, 19 février 2013 19h30 17 février 2013 17h Paolo Arrivabeni direction Valérie Nègre mise en scène Andrea Blum scénographie Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Alejandro Leroux lumières Sophie Tellier choréraphie Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Alice Coote, Celso Albelo, Ludovic Tézier, Service de presse Carlo Colombara, Loïc Félix, Judith Gauthier tél. 01 49 52 50 70 [email protected] Orchestre National de France Chœur de Radio France theatrechampselysees.fr Chœur du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Radio France La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la Réservations programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. 01 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr 5 Depuis quelques saisons, le bel canto La Favorite et tout particulièrement Donizetti ont naturellement trouvé leur place au Gaetano Donizetti Théâtre puisque pas moins de quatre des opéras du compositeur originaire Opéra en quatre actes (1840, version française) de Bergame ont été récemment Livret d’Alphonse Royer et Gustave Vaëz, d’après Les Amours malheureuses présentés : la trilogie qu’il a consacré ou Le Comte de Comminges de François-Thomas-Marie de Baculard d’Arnaud aux Reines de la cour Tudor (Maria Stuarda, Roberto Devereux et Anna Bolena) donnée en version de direction musicale Paolo Arrivabeni concert et, la saison dernière, Don Valérie Nègre mise en scène Pasquale dans une mise en scène de Andrea Blum scénographie Denis Podalydès. Guillaume Poix dramaturgie Aurore Popineau costumes Compositeur prolifique, héritier de Rossini et précurseur de Verdi, Alejandro Le Roux lumières Donizetti appartient à cette lignée de chorégraphie Sophie Tellier musiciens italiens qui triomphèrent dans leur pays avant de conquérir Paris. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor

LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR An in-depth guide by Stu Lewis INTRODUCTION In Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857), Western literature’s prototypical “Desperate Housewives” narrative, Charles and Emma Bovary travel to Rouen to attend the opera, and they attend a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor. Perhaps Flaubert chose this opera because it would appeal to Emma’s romantic nature, suggesting parallels between her life and that of the heroine: both women forced into unhappy marriages. But the reason could have been simpler—that given the popularity of this opera, someone who dropped in at the opera house on a given night would be likely to see Lucia. If there is one work that could be said to represent opera with a capital O, it is Lucia di Lammermoor. Lucia is a story of forbidden love, deceit, treachery, violence, family hatred, and suicide, culminating in the mother of all mad scenes. It features a heroic yet tragic tenor, villainous baritones and basses, a soprano with plenty of opportunity to show off her brilliant high notes and trills and every other trick she learned in the conservatory, and, to top it off, a mysterious ghost haunting the Scottish Highlands. This is not to say that Donizetti employed clichés, but rather that what was fresh and original in Donizetti's hands became clichés in the works of lesser composers. As Emma Bovary watched the opera, “She filled her heart with the melodious laments as they slowly floated up to her accompanied by the strains of the double basses, like the cries of a castaway in the tumult of a storm. -

Anna Bolena Opera by Gaetano Donizetti

ANNA BOLENA OPERA BY GAETANO DONIZETTI Presentation by George Kurti Plohn Anna Bolena, an opera in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, is recounting the tragedy of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of England's King Henry VIII. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style, meaning beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, prevalent during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was born in 1797 and died in 1848, at only 51 years of age, of syphilis for which he was institutionalized at the end of his life. Over the course of is short career, Donizetti was able to compose 70 operas. Anna Bolena is the second of four operas by Donizetti dealing with the Tudor period in English history, followed by Maria Stuarda (named for Mary, Queen of Scots), and Roberto Devereux (named for a putative lover of Queen Elizabeth I of England). The leading female characters of these three operas are often referred to as "the Three Donizetti Queens." Anna Bolena premiered in 1830 in Milan, to overwhelming success so much so that from then on, Donizetti's teacher addressed his former pupil as Maestro. The opera got a new impetus later at La Scala in 1957, thanks to a spectacular performance by 1 Maria Callas in the title role. Since then, it has been heard frequently, attracting such superstar sopranos as Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Montserrat Caballe. Anna Bolena is based on the historical episode of the fall from favor and death of England’s Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII. -

Roberto Devereux

GAETANO DONIZETTI roberto devereux conductor Opera in three acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano, production Sir David McVicar after François Ancelot’s tragedy Elisabeth d’Angleterre set designer Sir David McVicar Saturday, April 16, 2016 costume designer 1:00–3:50 PM Moritz Junge lighting designer New Production Paule Constable choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Roberto Devereux was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund The presentation of Donizetti’s three Tudor queen operas this season is made possible through a generous grant from Daisy Soros, general manager in memory of Paul Soros and Beverly Sills Peter Gelb music director James Levine Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera principal conductor Fabio Luisi and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées 2015–16 SEASON The seventh Metropolitan Opera performance of GAETANO DONIZETTI’S This performance roberto is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– devereux Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, conductor America’s luxury Maurizio Benini homebuilder®, with generous long-term in order of vocal appearance support from sar ah (sar a), duchess of not tingham The Annenberg Elīna Garanča Foundation, The Neubauer Family queen eliz abeth (elisabet ta) Foundation, the Sondra Radvanovsky* Vincent A. Stabile Endowment for lord cecil Broadcast Media, Brian Downen and contributions from listeners a page worldwide. Yohan Yi There is no sir walter (gualtiero) r aleigh Toll Brothers– Christopher Job Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall robert (roberto) devereux, e arl of esse x today. Matthew Polenzani This performance is duke of not tingham also being broadcast Mariusz Kwiecien* live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on a servant of not tingham SiriusXM channel 74. -

Gli Esiliati in Siberia, Exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson

Gli esiliati in Siberia, exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson How many times did Donizetti write or rewrite Otto mesi in due ore. No one has ever been quite sure: at least five times, perhaps seven - it depends how the changes he made are viewed. Between 1827 and 1845 he set and reset the music of this strange but true tale of heroism - of the eighteen-year-old daughter who struggled through snow and ice for eight months to plead with the Tsar for the release of her father from exile in Siberia, making endless changes - giving it a handful of titles, six different poets supplying new verses (including the maestro himself), with- and-without spoken dialogue, with-and-without Neapolitan dialect, with-and-without any predictable casting (the prima donna could be a soprano, mezzo-soprano or contralto at will), and with-and-without any very enduring resolution at the end so that this extraordinary work has an even-more-fantastic choice of synopses than usual. It was this score that stayed with him throughout his years of international fame even when Lucia di Lammermoor and Don Pasquale were taking the world by storm. It is perfectly possible in fact that the music of his final revision of Otto mesi in due ore was the very last to which he turned his stumbling hand before mental collapse put an end to his hectic career. How did it come by its peculiar title? In 1806 Sophie Cottin published a memoir in London and Paris of a real-life Russian heroine which she called 'Elisabeth, ou Les Exilés de Sibérie'. -

Gaetano Donizetti

Gaetano Donizetti ORC 3 in association with Box cover : ‘ Eleonore, Queen of Portugal’ by Joos van Cleve, 1530 (akg-images/Erich Lessing) Booklet cover : The duel, a scene from Gioja’s ballet Gabriella di Vergy , La Scala, Milan, 1826 Opposite : Gaetano Donizetti CD faces: Elizabeth Vestris as Gabrielle de Vergy in Pierre de Belloy’s tragedy, Paris, 1818 –1– Gaetano Donizetti GABRIELLA DI VERGY Tragedia lirica in three acts Gabriella.............................................................................Ludmilla Andrew Fayel, Count of Vergy.......................................................Christian du Plessis Raoul de Coucy......................................................................Maurice Arthur Filippo II, King of France......................................................John Tomlinson Almeide, Fayel’s sister...................................................................Joan Davies Armando, a gentleman of the household...................................John Winfield Knights, nobles, ladies, servants, soldiers Geoffrey Mitchell Choir APPENDIX Scenes from Gabriella di Vergy (1826) Gabriella..............................................................................Eiddwen Harrhy Raoul de Coucy............................................................................Della Jones Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Conductor: Alun Francis –2– Managing director: Stephen Revell Producer: Patric Schmid Assistant conductor: David Parry Consultant musicologist: Robert Roberts Article and synopsis: Don White English libretto: -

Linda Di Chamounix Lib.Indd

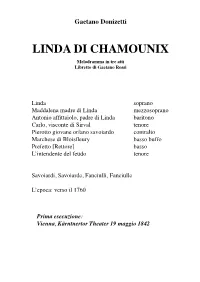

Gaetano Donizetti LINDA DI CHAMOUNIX Melodramma in tre atti Libretto di Gaetano Rossi Linda soprano Maddalena madre di Linda mezzosoprano Antonio affittaiolo, padre di Linda baritono Carlo, visconte di Sirval tenore Pierotto giovane orfano savoiardo contralto Marchese di Bloisfleury basso buffo Prefetto [Rettore] basso L’intendente del feudo tenore Savoiardi, Savoiarde, Fanciulli, Fanciulle L’epoca: verso il 1760 Prima esecuzione: Vienna, Kärntnertor Theater 19 maggio 1842 Donizetti: Linda di Chamounix - atto primo Sinfonia ATTO PRIMO La partenza Scena I° L’aurora; il sole va poi gradatamente illuminando la scena. Interno di una cascina. A destra, verso il fondo, la porta di una stanza. Una rustica sedia a bracciuoli, vicina. Una panca, qualche sedia. Il pro- spetto è aperto e da esso scorgesi un sito pittoresco sulle montagne di Savoia e parte del villaggio. Una chiesa sull’alto. Si odono gli ultimi rintocchi d’una campana e varie voci da opposte parti: si vedono poi uomini, donne, fan- ciulli avviarsi al tempio, poi Maddalena, indi Antonio. Coro di introduzione ANTONIO (entrando un po’ cupo) CORO Moglie! (da lontano) Presti! Al tempio! Delle preci MADDALENA Diè il segnal la sacra squilla. Già del sole ormai scintilla (con premura) Sulle cime il primo raggio, Ebbene? Or dal ciel fausto viaggio Cominciamo ad implorar: ANTONIO La speranza ed il coraggio (esita) Non potranno vacillar. L’Intendente sperar mi fe’ propizia (Apresi la stanza a destra e vi esce pian piano Mad- Sua Eccellenza; il fratel della Marchesa dalena, che si ferma sulla soglia) Nostra padrona. Recitativo MADDALENA MADDALENA S’egli è così, respiro. Ei può tutto, speriamo. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

Roger Parker: Curriculum Vitae

1 Roger Parker Publications I Books 1. Giacomo Puccini: La bohème (Cambridge, 1986). With Arthur Groos 2. Studies in Early Verdi (1832-1844) (New York, 1989) 3. Leonora’s Last Act: Essays in Verdian Discourse (Princeton, 1997) 4. “Arpa d’or”: The Verdian Patriotic Chorus (Parma, 1997) 5. Remaking the Song: Operatic Visions and Revisions from Handel to Berio (Berkeley, 2006) 6. New Grove Guide to Verdi and his Operas (Oxford, 2007); revised entries from The New Grove Dictionaries (see VIII/2 and VIII/5 below) 7. Opera’s Last Four Hundred Years (in preparation, to be published by Penguin Books/Norton). With Carolyn Abbate II Books (edited/translated) 1. Gabriele Baldini, The Story of Giuseppe Verdi (Cambridge, 1980); trans. and ed. 2. Reading Opera (Princeton, 1988); ed. with Arthur Groos 3. Analyzing Opera: Verdi and Wagner (Berkeley, 1989); ed. with Carolyn Abbate 4. Pierluigi Petrobelli, Music in the Theater: Essays on Verdi and Other Composers (Princeton, 1994); trans. 5. The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (Oxford, 1994); translated into German (Stuttgart. 1998), Italian (Milan, 1998), Spanish (Barcelona, 1998), Japanese (Tokyo, 1999); repr. (slightly revised) as The Oxford History of Opera (1996); repr. paperback (2001); ed. 6. Reading Critics Reading: Opera and Ballet Criticism in France from the Revolution to 1848 (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Mary Ann Smart 7. Verdi in Performance (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Alison Latham 8. Pensieri per un maestro: Studi in onore di Pierluigi Petrobelli (Turin, 2002); ed. with Stefano La Via 9. Puccini: Manon Lescaut, special issue of The Opera Quarterly, 24/1-2 (2008); ed. -

What the Critics Say As Primo Tenore/Principal Tenor

DAVID KELLETT TENOR What the critics say as primo tenore/principal tenor... Return of Ulysses Town Topics “The two meatier tenor roles of the opera were allocated to non-students; University Lecturer David Kellett sang the role of Eumaeus the shepherd with a relentless protectiveness of Penelope. The register and musical style of this role clearly foreshadowed the operatic vocal style of such later composers as Handel, and Mr. Kellett was effective in maintaining the required stamina.” Alice in Wonderland Town Topics “Tenor David Kellett is always solid on an operatic stage, and has participated in a number of Westergaard premieres. He and Ms. Jolicoeur performed well in tandem as two heads of the “Caterpillar,” and as the “Mad Hatter” (with a great purple hat), he helped bring the scene to the appropriate level of confusion.” New York Times “The other singers…David Kellett, tenor… were all in strong voice and met Mr. Westergaard’s demands with flexibility and energy.” The Magic Flute The Star Ledger "Kellett's tenor was ardent and clear." Classical New Jersey “David Kellett's voice has been an instrument that I have found appealing since I first heard him over 20 years ago. He had a refreshing lyric quality then that was sufficient in carrying power up to his higher register where it would take on a slightly driven quality. He always reminded me of having a smoothness like "Tito Schipa" several generations ago. Kellett’s voice is a finely produced instrument, and he has retained that smoothness of line and production throughout the registers even as age has darkened the tone and added weight. -

The Musical Journal (1840) Copyright © 2005 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire International De La Presse Musicale ( the Musical Journal (1840)

Introduction to: Richard Kitson, The Musical Journal (1840) Copyright © 2005 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) The Musical Journal (1840) The Musical Journal, a magazine of information, on all subjects connected with the science [MUJ] was issued weekly in London on Tuesdays between 7 January and 29 December 1840, under the proprietorship of W. Mitchell and Son at 39 Charing Cross, and printed by J. Limbird at 143, Strand. In all only forty-five issues were distributed, for by Volume II, no. 43, 27 October 1840 the editor became aware of the need for termination owing to the general decline in provincial concerts (the festivals) and professional concerts and operas in London.1 Thus no issues were published in November, and only three biweekly issues appeared in December. Each issue contains sixteen pages with the exception of Volume II, no. 28, which has only fourteen. Volume I contains issue numbers 1 through 26 (7 January to 30 June, 1840), while Volume II contains numbers 27 through 46, (7 July to 29 December, 1840).2 The journal’s 730 pages are printed in single-column format, and the pages are numbered consecutively in each volume. Indices for both volumes are given at the outset of each half-year in the New York Public Library microfilm copy of the journal used for this RIPM publication.3 The names of the editors are not given in the journal, and all texts relating to it, which might be attributed to an editor, are unsigned. In fact, signatures (names, initials and pseudonyms) are given only for those who contributed letters to the editor, and texts borrowed from other publications.