Lesson Learnt from Bidayuh Annah Rais Longhouse Tourism’S Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

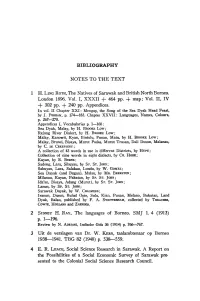

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

Sarawak Map Serian Serian Serian Division Map Division

STB/2019/DivBrochure/Serian/V1/P1 Bank Simpanan Nasional Simpanan Bank 2. 1. RHB Bank RHB Siburan Sub District Sub Siburan Ambank 7. Hong Leong Bank Leong Hong 6. Public Bank Public 5. Bank Kerjasama Rakyat Kerjasama Bank 4. obank Agr 3. CIMB Bank CIMB 2. 1. Bank Simpanan Nasional Simpanan Bank Serian District Serian LIST OF BANKS BANKS OF LIST TML Remittance Center Serian Center Remittance TML 6. Bank Simpanan Nasional Simpanan Bank 5. Bank Rakyat Bank 4. Tel : 082-874 154 Fax : 082-874799 : Fax 154 082-874 : Tel o Bank o Agr 3. Ambank 2. Serian District Council Office Office Council District Serian 1. Serian District Serian (currently only available in Serian District) Serian in available only (currently Tel: 082-864 222 Fax: 082-863 594 082-863 Fax: 222 082-864 Tel: LIST OF REGISTERED MONEY CHANGER CHANGER MONEY REGISTERED OF LIST Siburan Sub District Office District Sub Siburan Youth & Sports Sarawak Sports & Youth ash & Dry & ash W 5. Ministry of Tourism, Arts, Culture, Arts, Tourism, of Ministry Tel: 082-797 204 Fax: 082-797 364 082-797 Fax: 204 082-797 Tel: Hi-Q Laundry Hi-Q 4. Tebedu District Office District Tebedu ess Laundry ess Dobi-Ku Expr Dobi-Ku 3. Serian Administrative Division Administrative Serian Laundry Bar Siburan Bar Laundry 2. 1. Laundry 17 Laundry Tel: 082-874 511 Fax: 082-875 159 082-875 Fax: 511 082-874 Tel: b) Siburan Sub District Sub Siburan b) Serian District Office Office District Serian asmeen Laundry asmeen Y 3. Tel : 082-872472 Fax : 082-872615 : Fax 082-872472 : Tel Laundry Bar Laundry 2. -

The Impact of Small and Medium Enterprises Dilemmas on Business Performance

THE IMPACT OF SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES DILEMMAS ON BUSINESS PERFORMANCE Siti Aisyah Ya’kob*, Kit-Kang Liew** & Norlina Kadri*** Siti Aisyah Ya’kob, Lecturer, Department of Business Management, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia, E-Mail: [email protected]* Kit-Kang Liew, Department of Business Management, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia, E-Mail: [email protected]** Norlina Kadri, Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia, E-Mail: [email protected]*** ABSTRACT Business performance is an important element in the business. Thus, the dilemma confronted by the small and medium enterprises will affect both financial and non-financial business performance. A study on the small and medium enterprises topic is not new but necessary in order to observe the effect of the considerable issues in business environment. Therefore, this study is conducted to investigate the dilemmas that affect the business performance among small and medium enterprises in service sector. Three dimensions have been proposed, which are transportation facilities, financial strength, and labor force skills. A total of 159 sets of questionnaires were completed by the firms’ representative. The findings from this study discovered that transportation facilities, financial strength, and labor force skills have a significant and positive relationship with business performance. The results present a better understanding of transportation facilities, financial strength, and labor force skills issues from small and medium enterprises in Kuching city, which is located in Borneo Island. Keyword – business performance, Sarawak, small and medium enterprises INTRODUCTION Small and medium sized industry is still in the works to grow day to day as it is a key driver for the nation development (The Borneo Post, 2012). -

English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs

CHAPTER 6 English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs Patricia Nora Riget and Xiaomei Wang Introduction Sarawak covers a vast land area of 124,450 km2 and is the largest state in Malaysia. Despite its size, its population of 2.4 million people constitutes less than one tenth of the country’s population of 30 million people (as of 2015). In terms of its ethnic composition, besides the Malays and Chinese, there are at least 10 main indigenous groups living within the state’s border, namely the Iban, Bidayuh, Melanau, Bisaya, Kelabit, Lun Bawang, Penan, Kayan, Kenyah and Kajang, the last three being collectively known as the Orang Ulu (lit. ‘upriver people’), a term that also includes other smaller groups (Hood, 2006). The Bidayuh (formerly known as the Land Dayaks) population is 198,473 (State Planning Unit, 2010), which constitutes roughly 8% of the total popula- tion of Sarawak. The Bidayuhs form the fourth largest ethnic group after the Ibans, the Chinese and the Malays. In terms of their distribution and density, the Bidayuhs are mostly found living in the Lundu, Bau and Kuching districts (Kuching Division) and in the Serian district (Samarahan Division), situated at the western end of Sarawak (Rensch et al., 2006). However, due to the lack of employment opportunities in their native districts, many Bidayuhs, especially youths, have migrated to other parts of the state, such as Miri in the east, for job opportunities and many have moved to parts of Peninsula Malaysia, espe- cially Kuala Lumpur, to seek greener pastures. Traditionally, the Bidayuhs lived in longhouses along the hills and were involved primarily in hill paddy planting. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia

International Journal of Marketing Studies www.ccsenet.org/ijms A Study on Trend of Logs Production and Export in the State of Sarawak, Malaysia Pakhriazad, H.Z. (Corresponding author) & Mohd Hasmadi, I Department of Forest Management, Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8946-7225 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study was conducted to determine the trend of logs production and export in the state of Sarawak, Malaysia. The trend of logs production in this study referred only to hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species detailed production. The trend of logs export was divided into selected species and destinations. The study covers the analysis of logs production and export for a period of ten years from 1997 to 2006. Data on logs production and export were collected from statistics published by the Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation (Statistic of Sarawak Timber and Timber Product), Sarawak Timber Association (Sarawak Timber Association Review), Hardwood Timber Sdn. Bhd (Warta) and Malaysia Timber Industry Board (MTIB). The trend of logs production and export were analyzed using regression model and times series. In addition, the relation between hill and peat swamp forest logs production with their species and trend of logs export by selected species and destinations were conducted using simple regression model and descriptive statistical analysis. The results depicted that volume of logs production and export by four major logs producer (Sibu division, Bintulu division, Miri division and Kuching division) for hill and peat swamp forest showed a declining trend. Result showed that Sibu division is the major logs producer for hill forest while Bintulu division is the major producer of logs produced for the peat swamp forest. -

Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan

Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, STB/2019/DivBrochure/Samarahan/V1/P1 JPA, No. 2 Lot 5452, Jalan Datuk Mohammad Musa, 94300 Kota Kota 94300 Musa, Mohammad Datuk Jalan 5452, Lot 2 No. JPA, Address : Address Tel : 082-505911 : Tel 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Kampus Institut Kemajuan Desa (INFRA) Cawangan Sarawak Cawangan (INFRA) Desa Kemajuan Institut Kampus Address : Address Wilayah Sarawak Wilayah Institut Tadbiran Awam Negara (INTAN) Kampus Kampus (INTAN) Negara Awam Tadbiran Institut Tel : 082-677 200 082-677 : Tel Jalan Meranek, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Meranek, Jalan Address : Address Cawangan Sarawak Cawangan Kampus Institut Kemajuan Desa (INFRA) (INFRA) Desa Kemajuan Institut Kampus Website: ipgmktar.edu.my Website: Fax: 082-672984 Fax: Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) Mara Teknologi Universiti Tel : 083 - 467 121/ 122 Fax : 083 - 467 213 467 - 083 : Fax 122 121/ 467 - 083 : Tel Youth & Sports Sarawak Sports & Youth Tel : 082-673800/082-673700 : Tel Sebuyau District Office District Sebuyau Ministry of Tourism, Arts, Culture, Arts, Tourism, of Ministry Jln Datuk Mohd Musa, Kota Samarahan, 94300 Kuching 94300 Samarahan, Kota Musa, Mohd Datuk Jln Tel : (60) 82 58 1174/ 1214/ 1207/ 1217/ 1032 1217/ 1207/ 1214/ 1174/ 58 82 (60) : Tel Address : Address Jalan Datuk Mohammad Musa, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak Samarahan, Kota 94300 Musa, Mohammad Datuk Jalan Samarahan Administrative Division Administrative Samarahan Address : Address Tel : 082 - 803 649 Fax : 082 - 803 916 803 - 082 : Fax -

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission

MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION INVITATION TO REGISTER INTEREST AND SUBMIT A DRAFT UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLAN AS A UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVIDER UNDER THE COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA (UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVISION) REGULATIONS 2002 FOR THE INSTALLATION OF NETWORK FACILITIES AND DEPLOYMENT OF NETWORK SERVICE FOR THE PROVISIONING OF PUBLIC CELLULAR SERVICES AT THE UNIVERSAL SERVICE TARGETS UNDER THE JALINAN DIGITAL NEGARA (JENDELA) PHASE 1 INITIATIVE Ref: MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Date: 20 November 2020 Invitation to Register Interest as a Universal Service Provider MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Page 1 of 142 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 INTERPRETATION ........................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION I – INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 8 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 8 SECTION II – DESCRIPTION OF SCOPE OF WORK .............................................................. 10 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FACILITIES AND SERVICES TO BE PROVIDED ....................................................................................................................................... 10 3. SCOPE OF -

Two New Monophyllaea (Gesneriaceae) Species from Sarawak, Borneo

Phytotaxa 129 (1): 59–64 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.129.1.6 Two new Monophyllaea (Gesneriaceae) species from Sarawak, Borneo RUTH KIEW1 & JULIA SANG2 1Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong, Selangor, Malaysia; e-mail: [email protected]; 2Botanical Research Centre, Sarawak Forestry, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two new species, Monophyllaea grandifolia Kiew & S.Julia and Monophyllaea meriraiensis Kiew & S.Julia are described from limestone hills in Ulu Merirai, Tatau District, Sarawak. Descriptions and photographs of the two species are provided. Key words: limestone hills, Malaysia, Monophyllaea subgen. Monophyllaea Introduction Sarawak is the center of diversity of Monophyllaea R.Brown (1838: 121) being home to 16 of the 24 currently known species (Burtt 1978, Weber 1998, Kiew 2002). In Sarawak the highest number of Monophyllaea are on limestone hills in the Kuching Division (8 species) and on the Melinau limestone (8 species) in Gunung Mulu National Park, with only the widespread M. merrilliana Kraenzlin (1913: 168) occurring in both areas. The remaining species is found on Bukit Sarang, an isolated limestone hill in the Tatau District. Exploration of the Ulu Merirai limestone, also in the Tatau District (02o 46′ 13.7′′ N, 113o 39′ 02.9′′ E), resulted in the discovery of two new Monophyllaea species, as well as five new species of Begonia Linnaeus (1753: 1056), Begoniaceae (Kiew & Sang 2009) and a new species of Amorphophallus Blume ex Decaisne (1834: 366), Araceae (Boyce & Hetterscheid 2010), indicating that this is an important, though still little known, limestone area in Sarawak. -

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Development of Tropical

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Earth Sci. Res. J. Vol. 20, No. 1 (March, 2016): O1 - O10 GEOLOGY ENGINEERING Development of Tropical Lowland Peat Forest Phasic Community Zonations in the Kota Samarahan-Asajaya area, West Sarawak, Malaysia Mohamad Tarmizi Mohamad Zulkifley1, Ng Tham Fatt1, Zainey Konjing2, Muhammad Aqeel Ashraf3,4* 1. Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2. Biostratex Sendirian Berhad, Batu Caves, Gombak, Malaysia. 3. Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, School of Environmental Studies, China University of Geosciences, 430074 Wuhan, P. R. China 4. Faculty of Science & Natural Resources, University Malaysia Sabah88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. Corresponding authors: Muhammad Aqeel Ashraf- Faculty of Science & Natural Resources University Malaysia Sabah, 88400, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Keywords: Lowland peat swamp, Phasic community, Logging observations of auger profiles (Tarmizi, 2014) indicate a vertical, downwards, general decrease of Mangrove swamp, Riparian environment, Pollen peat humification levels with depth in a tropical lowland peat forest in the Kota Samarahan-Asajaya área in the diagram, Vegetation Succession. región of West Sarawak (Malaysia). Based on pollen analyses and field observations, the studied peat profiles can be interpreted as part of a progradation deltaic succession. Continued regression of sea levels, gave rise Record to the development of peat in a transitional mangrove to floodplain/floodbasin environment, followed by a shallow, topogenic peat depositional environment with riparian influence at approximately 2420 ± 30 years B.P. Manuscript received: 20/10/2015 (until present time). The inferred peat vegetational succession reached Phasic Community I at approximately Accepted for publication: 12/02/2016 2380 ± 30 years B.P. -

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B

KKM HEADQUARTERS Division / Unit Activation Code PEJABAT Y.B. MENTERI 3101010001 PEJABAT Y.B. TIMBALAN MENTERI 3101010002 PEJABAT KETUA SETIAUSAHA 3101010003 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (PENGURUSAN) 3101010004 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA SETIAUSAHA (KEWANGAN) 3101010005 PEJABAT KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN 3101010006 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PERUBATAN) 3101010007 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (KESIHATAN AWAM) 3101010008 PEJABAT TIMBALAN KETUA PENGARAH KESIHATAN (PENYELIDIKAN DAN SOKONGAN TEKNIKAL) 3101010009 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN) 3101010010 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (PERKHIDMATAN FARMASI) 3101010011 PEJABAT PENGARAH KANAN (KESELAMATAN DAN KUALITI MAKANAN) 3101010012 BAHAGIAN AKAUN 3101010028 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN FARMASI 3101010047 BAHAGIAN AMALAN DAN PERKEMBANGAN KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010042 BAHAGIAN AMALAN PERUBATAN 3101010036 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN HUBUNGAN ANTARABANGSA 3101010019 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK FARMASI 3101010050 BAHAGIAN DASAR DAN PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK KESIHATAN PERGIGIAN 3101010043 BAHAGIAN DASAR PERANCANGAN STRATEGIK DAN STANDARD CODEX 3101010054 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PENYAKIT 3101010030 BAHAGIAN KAWALAN PERALATAN PERUBATAN 3101010055 BAHAGIAN KAWALSELIA RADIASI PERUBATAN 3101010041 BAHAGIAN KEJURURAWATAN 3101010035 BAHAGIAN KEWANGAN 3101010026 BAHAGIAN KHIDMAT PENGURUSAN 3101010023 BAHAGIAN PEMAKANAN 3101010033 BAHAGIAN PEMATUHAN DAN PEMBANGUNAN INDUSTRI 3101010053 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN 3101010020 BAHAGIAN PEMBANGUNAN KESIHATAN KELUARGA 3101010029 BAHAGIAN