Goal 9, Population & Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bay, Oregon, with Notes on Shehfish Temperature, and Physical

COASTAL RIVERS I NFORMAT I ON Observations onon FishFish LiistributDistribution ion inin TillamookTillamook Bay, Oregon,Oregon, wi-f-h with NotesNotes on ShellfishSheHfish Temperature, and Physical Characteristics by T. Edwin Cummings Richard L. Berry Fish Commission of Oregon Management and Research Division This work was conducted in cooperation with -f-hethe NationaJ National Marine Fisheries Service under the AnadromousFish Act PL 89-304 April 19741974 4 CONTENTS Page No. I NTRODUCT I(ON ON DESCRIPTION OF ThETHE AREA. METHODS.......................................................... 4 Seining Sites. 4 Equipment . 5 Data Recorded 5 RESULTS ..................................................................................................................... 5 Coho. Chinook. Herr! ng. .................................................... 12 Smell-..ei I 2 Sole..So I e.. 13 StanyFyFlounder Flounder............................................................ 13 SurfPerch .................................................................................................... 13 Col-tids....................... .,....... ..................... 14 MiscellaneousMiscellaneousFish Fish SpeciesSpecies.................................. 14 Shellfish................................................... 14 Temperature ................................................. 17 DISCUSSION. 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. 19 LITERATURE CITED. 19 APPEND IX 20 FIGURES fj9urefure No.No. Page No. I Map of Tillamook Bay,Bay, OregonOregon 3 2 Presence ofof FishesFishes inin thethe Ti -

DOGAMI TIM-Till-05, Plate 1: Local-Source (Cascadia Subduction Zone) Tsunami Inundation Map for Garibaldi

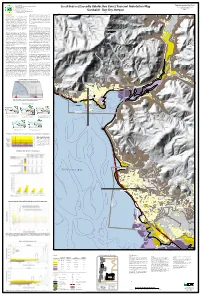

STATE OF OREGON Tsunami Inundation Map Till-05 DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Tsunami Inundation Maps for Garibaldi - Bay City, www.OregonGeology.org Local Source (Cascadia Subduction Zone) Tsunami Inundation Map Tillamook County, Oregon Larry Givens, Governing Board Chair Vicki S. McConnell, Director and State Geologist Plate 1 Don W.T. Lewis, Assistant Director Rachel R. Lyles Smith, Project Operations Manager Garibaldi - Bay City, Oregon Ian P. Madin, Chief Scientist 2012 123°56'0"W 123°54'0"W 123°52'0"W Introduction displacement of the Pacific Ocean, resulting in an increase of the tsunami inundation onshore in Oregon. DOGAMI has also The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries incorporated physical evidence that suggests that portions of the 200 (DOGAMI) has been identifying and mapping the tsunami inundation coast may drop 4 to 10 feet during the earthquake; this effect is hazard along the Oregon coast since 1994. In Oregon, DOGAMI known as subsidence. Detailed information on fault geometries, 100 manages the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, which subsidence, computer models, and the methodology used to create has been administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric the tsunami scenarios presented on this map can be found in Administration (NOAA) since 1995. DOGAMI’s work is designed to DOGAMI Special Papers 41 (Priest and others, 2009) and 43 (Witter help cities, counties, and other sites in coastal areas reduce the and others, 2011). potential for disastrous tsunami-related consequences by understanding and mitigating this geologic hazard. Using federal Map Explanation funding awarded by NOAA, DOGAMI has developed a new generation of tsunami inundation maps to help residents and visitors along the This tsunami inundation map displays the output of computer entire Oregon coast prepare for the next Cascadia Subduction Zone models representing five selected tsunami scenarios, all of which (CSZ) earthquake and tsunami. -

On Foot Scampering Over Tree Roots

5. Netarts/Happy Camp Beaches Safety & Etiquette Netarts has two good beach access points, 7-9 Cape Lookout • Pack it in, pack it out. Cape to Cape with restrooms at both. Just north of the These hikes are longer and more • Keep dogs on leash. village of Netarts, take Happy Camp Road ! strenuous than the other hikes in this • Watch children closely. west down the hill. At the end of the road you guide. Be prepared for muddy sections and • Do not climb cliffs or walk out will find a gravel parking lot near the mouth on Foot scampering over tree roots. Wear good onto rock faces. of Netarts Bay. From the parking lot, you can shoes, carry water, and plan for unpredictable Netarts Area Trails and Beach Walks • Be prepared for sudden walk to the south along the bay or to the changes in weather. Cape Lookout can be weather changes. from Cape Meares to Cape Lookout north with great views of Three Arch Rocks. very windy or become shrouded in fog quickly. This area has strong tidal currents and is • Watch for sneaker waves. unsafe for swimming. Jim Young In Netarts, turn west off the main highway 7. North Trail at Netarts Bay Drive. You will immediately Jim Young see Netarts Bay and the County Boat Ramp North Trail crosses the cape and follows the parking lot. From the lot, walk west about coastline north 2.3 miles (4.6 miles round-trip) 100 yards to the bay beach. A day-use through the shaded forest and down to the parking fee is required. -

Sediment Accumulation in Tillamook Bay, Oregon: Natural Processes Versus Human Impacts

Sediment Accumulation in Tillamook Bay, Oregon: Natural Processes versus Human Impacts Paul D. Komar, James McManus, and Michael Styllas College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Tillamook Bay on the northern Oregon coast has experienced significant sediment accumulation and shoaling. Anal- yses show that part of the increased sedimentation was a result of substantial human impacts in the watersheds of the five rivers that drain into the bay. River discharges were enhanced by approximately 13% during the period 1931– 1954, when commercial logging and a series of devastating forest fires occurred, compared with discharges in the years after reforestation. Potential annual sediment yields calculated from daily discharges were enhanced by 29% during 1931–1954, but actual yields would have been substantially greater as a result of increased erosion rates because of deforestation. Sand transported by the rivers consists primarily of rock fragments, in contrast to the quartz and feldspar sand carried into the bay from the ocean beach. Surface sediments collected throughout the bay consist, on average, of about 40% sand from the rivers and 60% from the ocean beach. Cores show increasing percentages of beach sand beneath the surface, with evidence for major episodic inputs rather than the higher percentages of river- derived rock fragments that human impacts would have produced. Subduction earthquakes have struck the Oregon coast repeatedly during the past several thousand years; the most recent was in January 1700. The down-core increase in beach-derived sand in Tillamook Bay is from sand transport by the tsunami that accompanied the 1700 earthquake and the deepening of the bay from land subsidence at the time of the earthquake, which permitted more frequent and extensive spit overwash events during storms. -

History of the Siletz This Page Intentionally Left Blank for Printing Purposes

History of the Siletz This page intentionally left blank for printing purposes. History of the Siletz Historical Perspective The purpose of this section is to discuss the historic difficulties suffered by ancestors of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (hereinafter Siletz Indians or Indians). It is also to promote understanding of the ongoing effects and circumstances under which the Siletz people struggle today. Since time immemorial, a diverse number of Indian tribes and bands peacefully inhabited what is now the western part of the State of Oregon. The Siletz Tribe includes approximately 30 of these tribes and bands.1 Our aboriginal land base consisted of 20 million acres located from the Columbia to the Klamath River and from the Cascade Range to the Pacific Ocean. The arrival of white settlers in the Oregon Government Hill – Siletz Indian Fair ca. 1917 Territory resulted in violations of the basic principles of constitutional law and federal policy. The 1787 Northwest Ordinance set the policy for treatment of Indian tribes on the frontier. It provided as follows: The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in the property, rights, and liberty, they never shall be invaded, or disturbed, unless in just, and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace, and friendship with them. 5 Data was collected from the Oregon 012.5 255075100 Geospatial Data Clearinghouse. -

Tillamook Bay Watershed

Tillamook Bay Watershed (Portions extracted from “Tillamook Bay Environmental Characterization: A Scientific and Technical Summary”, Tillamook Bay National Estuary Project, July 1998) WATER QUALITY CONCERNS: The federal Clean Water Act (CWA) requires each state to undertake specific activities to protect the quality of their rivers, estuaries and lakes. DEQ is required to develop and implement water quality standards that protect sensitive beneficial uses of waters throughout Oregon. Section 303(d) of the CWA requires each state to develop a list of waters that do not meet the water quality standards. These are called Water Quality Limited waters. The Tillamook Bay Watershed is Water Quality Limited for Temperature and Bacteria. The number of segments and parameters that exceed water quality standards in the Tillamook Watershed are summarized below. In addition, sedimentation is a parameter of concern throughout the basin and several sloughs in the lower watershed have low dissolved oxygen levels. For more information on streams that are listed in the Tillamook watershed, go to: http://waterquality.deq.state.or.us/WQLData/SubBasinList98.asp. Water Quality Limited Waters in Tillamook (from 1998 303(d) List) Total Number of Water Bodies Listed 20 Parameter Number of Segments Listed Bacteria 15 Temperature 12 Total Maximum Daily Loads: The CWA further requires DEQ to develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for all water quality limited waters. Generally speaking, TMDLs define the maximum amount of controllable impacts a water body can accept and still assure that designated beneficial uses are being adequately protected. DEQ has developed TMDLs for temperature and bacteria in the Tillamook Bay Watershed. -

RESULTS of BACTERIA SAMPLING in the WILSON RIVER Joseph M

RESULTS OF BACTERIA SAMPLING IN THE WILSON RIVER Joseph M. Bischoff and Timothy J. Sullivan April 1999 Report Number 97-16-02 E&S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. P.O. Box 609 Corvallis, OR 97339 ABSTRACT Water quality monitoring was conducted at eight sites on the Wilson River during the period late September, 1997 through early March, 1998, from river mile 8.6 to river mile 0.2 near where the river enters Tillamook Bay. Samples were collected approximately weekly by the Tillamook County Creamery Association (TCCA) during the course of the study, plus at more frequent intervals during two storm events in October, 1997 and March, 1998. Samples were analyzed by TCCA for fecal coliform bacteria (FCB) and E. coli. E&S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. provided the data analysis and presentation for this report. FCB concentrations and loads in the Wilson River were higher by a factor of two during the October, 1997 storm than during any of the other five storms monitored by TCCA or E&S. Similar results were found for the Tillamook and Trask Rivers by Sullivan et al. (1998b). Lowest loads in the Wilson River were found during the monitored spring storms in 1997 (by E&S) and 1998 (this study). By far the highest FCB loads were contributed by the land areas that drain into Site 7 (in the mixing zone just below the TCCA outfall) during the October 1997 and March 1998 storms. This site was the only site in the Wilson River basin that has contributing areas occupied by urban land use. Relatively high FCB loads were also found at a variety of other sites. -

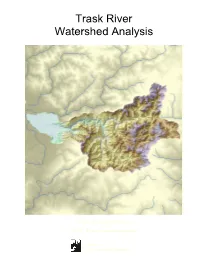

Trask River Watershed Analysis

Trask River Watershed Analysis TRASK RIVER WATERSHED ANALYSIS FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2003 A Report by E&S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. P.O. Box 609 Corvallis, OR 97339 Kai U. Snyder Timothy J. Sullivan Deian L. Moore Richard B. Raymond Erin H. Gilbert Submitted to Oregon Department of Forestry and U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Land Management John Hawksworth, Project Manager Trask River Watershed Analysis ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... x LIST OF TABLES......................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .........................................................................................................xiv CHAPTER 1. CHARACTERIZATION...................................................................................1-1 1.1 Physical ........................................................................................................1-1 1.1.1 Size and Setting ..........................................................................................1-1 1.1.2 Topography.................................................................................................1-1 1.1.3 Ecoregions..................................................................................................1-3 1.1.4 Geology and Geomorphology.....................................................................1-3 1.1.5 Soils ........................................................................................................1-5 -

Tillamook Bay Fish Use of the Estuary

1999 Monitoring Report TILLAMOOK BAY FISH USE OF THE ESTUARY Prepared for The Tillamook Bay National Estuary Project And Tillamook County Cooperative Partnership Garibaldi, Oregon Prepared by Robert H. Ellis, Ph. D. Ellis Ecological Services, Inc 20988 S. Springwater Rd. Estacada, Oregon 97023 October 22, 1999 SUMMARY In 1999, a Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP) was completed for the Tillamook Bay watershed. The CCMP lays out a variety of management actions designed, in part, to achieve the goal of protecting and restoring estuarine habitat for improvement of the fishery resources of Tillamook Bay and its watershed. Baseline information on the present status of the estuary's fish community and periodic updating of the baseline information through monitoring were identified as essential for evaluation of the CCMP's management actions. This study was conducted to describe the present status of the fish community in Tillamook Bay and to design and test a long-term monitoring strategy for fish. The study was conducted during the summer and autumn of 1998 and the spring and summer of 1999. The fish sampling done in 1998 was used to provide an estuary-wide overview of the fish species composition and relative abundance during the mid-summer period and to test sampling gear and sampling strategies for development of a long-term monitoring program. The sampling conducted in 1999 built upon the information gained in 1998 and provided an initial test of a sampling design for long-term monitoring of the Bay's fish community. Current fish use of the estuary was described by updating the comprehensive fish survey data collected by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) during the mid- 1970s. -

SPRING Term Schedule 2021

2021 Spring Term Course Schedule 1 SPRING term schedule 2021 REGISTRATION OPENS MARCH 1, 2021 WWW.TILLAMOOKBAYCC.EDU SPRING TERM 2 Tillamook Bay Community College IMPORTANT DATES TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW AT TBCC Spring Term 2021 4 6 WHERE TO FIND ASSISTANCE March 1 NEWS YOU CAN USE Registration Opens 7 8 GETTING STARTED AT TBCC March 20 LEGEND FOR READING THIS SCHEDULE Winter Term Ends 10-11 12 CREDIT COURSES March 29 - April 2 Spring Break 19-20 PRE-COLLEGE/GED/ESOL April 4 24-26 WORKFORCE & CAREER TRAINING Last Day to Register for Spring Term 25 SMALL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CENTER April 5 29 COMMUNITY EDUCATION First Day of Spring Term 31 FITNESS & HEALTH: YMCA May 21 Last day to Withdraw 35 FITNESS & HEALTH: NCRD STUDENT RESOURCES May 24 42 Summer Term Registration Opens 44 POLICIES & INFORMATION May 31 47 DIRECTORY Memorial Day 48 DEGREES & CERTIFICATES June 6 49 NON-CREDIT COURSE APPLICATION Last Day to Register for Summer Term June 12 Spring Term Ends Cover Photo: Forestry student Olivia Hooley exploring influences June 18 on microclimate near Anderson Hill Graduation during Forest Biology last fall. June 28 Photo by Megan Deane-McKenna. Summer Term Begins February 25, 2021 2:40 PM This publication is intended to inform students and residents about Tillamook Bay Community College’s programs and services. It includes a listing of classes for the term and information about how to register. Every effort has been made to insure accuracy at the time of publication; however, the College reserves the right to make changes without prior notice. -

Regional Framework for Climate Adaptation

Regional Framework for Climate Adaptation ClatsopRegional and Tillamook Framework Counties for Climate Adaptation Jeffrey A. Weber Oregon Coastal ClatsopManagement Program and Tillamook Counties February 2015 Project Management Team Jeffrey Weber, Climate Change Specialist and Coastal Conservation Coordinator, Oregon Coastal Management Program, Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development Joe Cone, Assistant Director and Communications Leader, Oregon Sea Grant Project Researchers, Assistants, and Facilitators Oregon Sea Grant: Patrick Corcoran, Monty Johnson, Miriah Kelly, and Kirsten Winters Climate Impacts Research Consortium and Oregon Sea Grant: John Stevenson Acknowledgments This regional framework could not have materialized without the assistance, support, and expertise of the project assistants and facilitators at Oregon Sea Grant and the Climate Impacts Research Consortium. Several people reviewed preliminary versions of material originally developed in the work groups and provided detailed suggestions for important revisions. The framework has been improved considerably by assistance from Alyssa Mucken, Rachel Lovellford, Dave Jepsen, Dave Fox, Geoff Crook, Kevin Cupples, Rosemary Johnson, Brendon Haggerty, Emily York, Margaret Matter, Judith Callens, Steve Lucker, and Laren Woolley. Principal author: Jeffrey A. Weber, Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development; with contributions from Miriah RKelly, John Stevenson, and Joe Cone. Contributing editor: Joe Cone, Oregon Sea Grant. Copyediting, design, and layout: Rick Cooper, Oregon Sea Grant. Development of Regional Framework for Climate Adaptation for Clatsop and Tillamook Counties was supported in part with funding to the Oregon Coastal Management Program from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office for Coastal Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, adminis- tered by NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management. -

Tillamook Bay Water Trail Guidebook, a Segment of the Tillamook County Water Trail

You have successfully arrived at the Tillamook Bay Water Trail online guidebook. Please scroll down for your viewing pleasure. tillamook county water trail OREGON Tillamook Bay WATERSHED FLATWATER & WHITEWATER Produced by the Tillamook Estuaries Partnership Welcome to the WelcomeTillamook toBay the Watershed Nehalem The Tillamook Bay watershed begins as an extraordinary network of hillside creeks leading to five rivers that stream through majestic forests and green lowlands to eventually merge with the estuary and finish the long journey to the Pacific Ocean. This diversity of waterways lends itself to many non-motorized recreational opportunities. Exhilarating whitewater adventures and play spots to calm, placid, sunny day trips, and everything in between await you in this place. Encompassing a 597-square-mile watershed including the cities of Tillamook, Bay City, and Garibaldi, this guidebook is intended to help users locate public access, discover local amenities, be mindful of sensitive natural areas, and obtain detailed information regarding these waterways. Grab your gear, choose your adventure, and discover the natural beauty that awaits. Tillamook County Water Trail - The Vision The Tillamook County Water Trail encourages the quiet exploration and discovery of the ecological, historical, social, and cultural features of Tillamook County from the uplands to the ocean. The Water Trail is a recreational and educational experience that promotes and celebrates the value of Tillamook County’s waterways with direct benefit to the economic, social, and environmental well-being of the County. The Water Trail enhances the identity of Tillamook County by establishing an alternative, low-impact way to enjoy and appreciate the wonders of all five Tillamook County estuaries.