Fifty-One HARVARD REVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Actor Ben Miller will turn on Cirencester’s Christmas Lights Organisers of Cirencester’s Advent Festival are delighted to announce that comedian, actor and director Ben Miller will be their special guest this year to switch on the Christmas Lights. Ben is well known for the award winning comedy sketch show Armstrong & Miller and the long suffering sidekick Bough to Rowan Atkinson’s Johnny English. He has also enjoyed success in Primeval, Dr Who and disgruntled detective Richard Poole in crime series Death in Paradise. Ben lives just outside Cirencester. He says he loves the town for its fabulous restaurants, glorious shopping, and ever-friendly locals. He is also a fan of the Love Lane industrial estate, where he likes to browse tractors and outdoor clothing of all shades and varieties. The event, which is being organised by Cirencester Town Council, will take place on Saturday November 26th from 9.00am to 9.00pm culminating with the traditional switch on ceremony from 6.30pm with the lights on and a display by Cotswold Fireworks at 7.00pm. What’s more, there will be lots of fun and surprises throughout the day as shops and businesses are being asked to help make Cirencester Sparkle by entering into the spirit of the day with special themes, entertainment and special promotions. Nick Brook, one of the organising team said “We are really pleased that so many shops this year are so keen to be part of making Advent Festival Day such a special one. We have some volunteers who have come forward to provide entertainment throughout the town during the day with busker style performances, street magic and colourful costumes and of course, we would welcome more. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

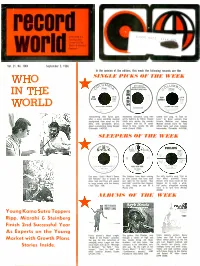

Ing the Fj Needs of the Music & Record Ti Ó+ Industry

. I '.k i 1 Dedicated To £15.o nlr:C, .3n0r14 Serving The fJ Needs Of The Music & Record ti Ó+ Industry ra - Vol. 21, No. 1004 September 3, 1966 In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK LU M MY UNCLE 6 USED TO LOVE IN THE ME BUT SHE DIED y 43192 WORLD JUST LIME A WOMAN Trendsetting Bob Dylan goes Absolutely nonsense song with Gentle love song, "A Time for after a more soothing musical gritty delivery by Miller. Should Love," by Oscar winners Paul background than usual on this catch ears across the country Francis Webster and Johnny ditty, with perceptive lyrics, as Roger, with his TV series Mandel should score for Tony about a precocious teeny bopper about to bow, recalls his odd whose taste and style remains (Columbia 4-43792). uncle (Smash 2055). impeccable (Columbia 4-43768). SLEEPERS OF THE WEEK PHILIPS Am. 7. EVIL ON YOUR MIND , SAID I WASN'T GONNAN TELL 0 00000 TERESA BREARE S AM t - DAVE A1 Duo does "Said I Wasn't Gonna The Uniques have been coming The nifty country song "Evil on Tell Nobody" like it should be up with sounds that have been Your Mind" provides Teresa done. Sam and Dave will appeal just right for the market. "Run Brewer with what could be her to large crowds with tfie bouncy and Hide" could be their biggest biggest hit in quite a while. r/ber (Stax 198). to date. Keep an eye on it Her perky, altogether winning (Paula 245). -

The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience Erica Rostedt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rostedt, Erica, "The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1665. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1665 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Erica Allison Rostedt B.A. University of Washington, 2004 May, 2013 © 2013, Erica Allison Rostedt ii Table -

MCA-500 Reissue Series

MCA 500 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-500 Reissue Series: MCA 500 - Uncle Pen - Bill Monroe [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5348. Jenny Lynn/Methodist Preacher/Goin' Up Caney/Dead March/Lee Weddin Tune/Poor White Folks//Candy Gal/Texas Gallop/Old Grey Mare Came Tearing Out Of The Wilderness/Heel And Toe Polka/Kiss Me Waltz MCA 501 - Sincerely - Kitty Wells [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5350. Sincerely/All His Children/Bedtime Story/Reno Airport- Nashville Plane/A Bridge I Just Can't Burn/Love Is The Answer//My Hang Up Is You/Just For What I Am/It's Four In The Morning/Everybody's Reaching Out For Someone/J.J. Sneed MCA 502 - Bobby & Sonny - Osborne Brothers [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5356. Today I Started Loving You Again/Ballad Of Forty Dollars/Stand Beside Me, Behind Me/Wash My Face In The Morning/Windy City/Eight More Miles To Louisville//Fireball Mail/Knoxville Girl/I Wonder Why You Said Goodbye/Arkansas/Love's Gonna Live Here MCA 503 - Love Me - Jeannie Pruett [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5360. Love Me/Hold To My Unchanging Love/Call On Me/Lost Forever In Your Kiss/Darlin'/The Happiest Girl In The Whole U.S.A.//To Get To You/My Eyes Could Only See As Far As You/Stay On His Mind/I Forgot More Than You'll Ever Know (About Her)/Nothin' But The Love You Give Me MCA 504 - Where is the Love? - Lenny Dee [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5366. -

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech 1 Elizabeth A. Kirley and Marilyn M. McMahon Emoji are widely perceived as a whimsical, humorous or affectionate adjunct to online communications. We are discovering, however, that they are much more: they hold a complex socio-cultural history and perform a role in social media analogous to non-verbal behaviour in offline speech. This paper suggests emoji are the seminal workings of a nuanced, rebus-type language, one serving to inject emotion, creativity, ambiguity – in other words ‘humanity’ - into computer mediated communications. That perspective challenges doctrinal and procedural requirements of our legal systems, particularly as they relate to such requisites for establishing guilt or fault as intent, foreseeability, consensus, and liability when things go awry. This paper asks: are we prepared as a society to expand constitutional protections to the casual, unmediated ‘low value’ speech of emoji? It identifies four interpretative challenges posed by emoji for the judiciary or other conflict resolution specialists, characterizing them as technical, contextual, graphic, and personal. Through a qualitative review of a sampling of cases from American and European jurisdictions, we examine emoji in criminal, tort and contract law contexts and find they are progressively recognized, not as joke or ornament, but as the first step in non-verbal digital literacy with potential evidentiary legitimacy to humanize and give contour to interpersonal communications. The paper proposes a separate space in which to shape law reform using low speech theory to identify how we envision their legal status and constitutional protection. 1 Dr. Kirley is Barrister & Solicitor in Canada and Seniour Lecturer and Chair of Technology Law at Deakin University, MelBourne Australia; Dr. -

Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2)

Harvard Library bibliography: Supplement (Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Carpenter, Kenneth E. 1996. Harvard Library bibliography: Supplement (Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2). Harvard Library Bulletin 6 (2), Summer 1995: 57-64. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42665395 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 57 Harvard Library Bibliography: Supplement his is a list of selected new books and articles of which any unit of the Harvard T University Library is the author, primary editor, publisher, or subject. The list also includes scholarly and professional publications by Library staff. The bibli- ography for 1960-1966 appeared in the Harvard Library Bulletin, 15 (1967), and supplements have appeared in the years following, most recently in Vol. 3 (New Series), No. 4 (Winter 1992-1993). The list below covers publications through mid-1995. Alligood, Elaine. "The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine: Poised for the Future, Guided by the Past," in Network News, the quarterly publication of the Massachu- setts Health Sciences Library Network (August 1994). (Elaine Alligood was formerly Assistant Director for Marketing in the Countway Library of Medicine.) Altenberger, Alicja and John W. Collins III. "Methods oflnstruction in Management for Libraries and Information Centers" in New Trends in Education and Research in Librarianshipand InformationScience (Poland:Jagiellonian University, 1993), ed. -

Emoticon Style: Interpreting Differences in Emoticons Across Cultures

Emoticon Style: Interpreting Differences in Emoticons Across Cultures Jaram Park Vladimir Barash Clay Fink Meeyoung Cha Graduate School of Morningside Analytics Johns Hopkins University Graduate School of Culture Technology, KAIST [email protected] Applied Physics Laboratory Culture Technology, KAIST [email protected] clayton.fi[email protected] [email protected] Abstract emotion not captured by language elements alone (Lo 2008; Gajadhar and Green 2005). With the advent of mobile com- Emoticons are a key aspect of text-based communi- cation, and are the equivalent of nonverbal cues to munications, the use of emoticons has become an everyday the medium of online chat, forums, and social media practice for people throughout the world. Interestingly, the like Twitter. As emoticons become more widespread emoticons used by people vary by geography and culture. in computer mediated communication, a vocabulary Easterners, for example employ a vertical style like ^_^, of different symbols with subtle emotional distinctions while westerners employ a horizontal style like :-). This dif- emerges especially across different cultures. In this pa- ference may be due to cultural reasons since easterners are per, we investigate the semantic, cultural, and social as- known to interpret facial expressions from the eyes, while pects of emoticon usage on Twitter and show that emoti- westerners favor the mouth (Yuki, Maddux, and Masuda cons are not limited to conveying a specific emotion 2007; Mai et al. 2011; Jack et al. 2012). or used as jokes, but rather are socio-cultural norms, In this paper, we study emoticon usage on Twitter based whose meaning can vary depending on the identity of the speaker. -

Stony Brook Press V. 19, N. 06.PDF (8.570Mb)

B 3. Vol. XIX No. 6 Don't Let The Door Hit Ya On The Tex-Ass November 12,1997 ISSUES Beyond Bubba University EMS and Fire Volunteers Practice Heavy Rescues By Michael Yeh mary responder for fires, vehicular extrication, bondage that comes with spinal immobilization. "I and hazardous materials," said SBVAC President never, ever want to be in a KED in my life," said The Stony Brook Volunteer Ambulance Corps Tim True. Christina Freudenberg, EMT-D of the tight jacket- paid its last respects to an old veteran -- by hack- "We need a new door there anyway," said like protective device. "But everybody was pretty ing it to pieces. Deputy Chief of Operations Jason Hellmann while cool, and they did a very good job." Emergency medical technicians and firefighters surveying the metallic carnage. "Until now, some "I felt that the technicians had control of what who serve the campus community participated in people thought heavy rescue meant a really fat was going on and were taking care of details that a heavy rescue drill at the Setauket Fire EMT named Bubba!" the accident victim would not normally be aware Department's Station 3 on SBVAC participants entered the of," said Kevin Kenny, EMT-Critical Care. Thursday, October 23. This was ambulance to find two other But most importantly, this drill gave the SBVAC the first mutual training event semi-conscious patients in the and Setauket volunteers a chance to see each other between SBVAC and neighbor- back. Since high-speed car acci- in action and to learn how to work together at a ing fire departments. -

The Year in Review

AY 2009-10 HARVARD COLLEGE WRITING PROGRAM The Year in Review YEAR IN REVIEW In the 2009-2010 academic year, the Harvard College Writing Program worked ambitiously to better integrate itself into the College and to The Expos Curriculum broaden its profile in the Harvard community. The past nine months page 2 have seen a number of exciting developments as our Program’s faculty members and administrative team have collaborated with many pro- grams, offices, and departmen ts in the College on our essential missions: Support for Undergraduate Writers to introduce our freshmen to the craft and practice of academic • page 3 writing through the Expository Writing curriculum; • to support, through the Harvard Writing Project, the teaching of Support for Faculty and undergraduate writing by Harvard faculty and Teaching Fellows; Teaching Fellows • to help undergraduates in all class years with their writing page 5 through a range of services, including peer-tutoring at our Writing Center, the Departmental Writing Fellows program, workshops on the research process, student writing guides in Harvard Writers at the disciplines, and our academic writing tutorial program in Work Lecture Series several Houses; and page 6 • to present opportunities for Harvard students and the public, through our new Harvard Writers at Work Lecture Series and Program-Sponsored other Program-sponsored events, to hear accomplished writ- Events for Writers ers in the Harvard community discuss their works, their writing lives, and the impact of writing on the world. page 7 The Writing Program wishes to thank its donors without whose generosity this past year’s numerous initiatives and services would Writing Program not have been possible. -

JOHN RODDA – Sound Mixer CORMORAN STRIKE (Series 2) Director: Susan Tully

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JOHN RODDA – Sound Mixer CORMORAN STRIKE (Series 2) Director: Susan Tully. Producer: Jackie Larkin. Starring: Tom Burke and Holliday Grainger. BBC. COME AWAY Director: Brenda Chapman. Producers: Angelia Jolie, Leesa Khan, Andrea Keir, David Oyelowo and James Spring. Starring: Angelia Jolie, Michael Caine and Gugu Mbatha-Raw. GEM Entertainment. THE SPLIT (Series 2) Director: Paula van der Oest. Producer: Natasha Romaniuk. Starring: Nicola Walker. Sister Pictures/AMC. WILD BILL Director: Annie Griffin. Producer: Chris Thompson. Starring: Rob Lowe. 42 / Anonymous Content / Shiver / ITV. FISHERMAN’S FRIENDS Director: Chris Foggin. Producers: Meg Leonard, Nick Moorcroft and James Spring. Starring: Tuppence Middleton, James Purefoy and Daniel Mays. Fred Films. THE ABC MURDERS Director: Alex Gabassi. Producer: Farah Abushwesha. Starring: John Malkovich, Eamon Farren and Michael Shaeffer. Mammoth Screen/Amazon Prime Video. 2019 Association of Motion Picture Sound (AMPS) nomination – Excellence in Sound Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JOHN RODDA Contd … 2 BLACK MIRROR: USS CALLISTER Director: Toby Haynes. Producer: Louise Sutton. Starring: Jesse Plemons, Cristin Milioti and Jimmi Simpson. Netflix. 2018 Cinema Audio Society (CAS) – Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing 2018 Association of Motion Picture Sound (AMPS) – Excellence in Sound BAFTA Nomination – Best Sound THAT GOOD NIGHT Director: Eric Styles. Producers: Alan Latham and Charles Savage. Starring: John Hurt, Sofia Helin and Max Brown. Goldfinch Studios/Eagle Films. HANK ZIPZER’S CHRISTMAS CATASROPHE Director: Matt Bloom. Producer: Matthew Mulot. Starring: Nick James, Neil Fitzmaurice and Juliet Cowan. -

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo Da Vinci) Tom Has Been Seen in A

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo da Vinci) Tom has been seen in a variety of TV roles, recently portraying Dr. Laurence Shepherd opposite James Nesbitt and Sarah Parish in ITV1’s critically acclaimed six-part medical drama series “Monroe.” Tom has completed filming the highly anticipated second season which premiered autumn 2012. In 2010, Tom played the role of Gavin Sorensen in the ITV thriller “Bouquet of Barbed Wire,” and was also cast in the role of Mr. Wickham in the ITV four-part series “Lost in Austen,” alongside Hugh Bonneville and Gemma Arterton. Other television appearances include his roles in Agatha Christie’s “Poirot: Appointment with Death” as Raymond Boynton, as Philip Horton in “Inspector Lewis: And the Moonbeams Kiss the Sea” and as Dr. James Walton in an episode of the BBC series “Casualty 1906,” a role that he later reprised in “Casualty 1907.” Among his film credits, Tom played the leading roles of Freddie Butler in the Irish film Happy Ever Afters, and the role of Joe Clarke in Stephen Surjik’s British Comedy, I Want Candy. Tom has also been seen as Romeo in St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold alongside Colin Firth and Rupert Everett and as the lead role in Santiago Amigorena’s A Few Days in September. Tom’s significant theater experiences originate from numerous productions at the Royal Court Theatre, including “Paradise Regained,” “The Vertical Hour,” “Posh,” “Censorship,” “Victory,” “The Entertainer” and “The Woman Before.” Tom has also appeared on stage in the Donmar Warehouse theatre’s production of “A House Not Meant to Stand” and in the Riverside Studios’ 2010 production of “Hurts Given and Received” by Howard Barker, for which Tom received outstanding reviews and a nomination for best performance in the new Off West End Theatre Awards.