The Over-Saturation Trend of High-End Apartment Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd Quarter Holdings

Calvert VP Russell 2000® Small Cap Index Portfolio September 30, 2020 Schedule of Investments (Unaudited) Common Stocks — 95.2% Security Shares Value Auto Components (continued) Security Shares Value Aerospace & Defense — 0.8% LCI Industries 2,130 $ 226,398 Modine Manufacturing Co.(1) 4,047 25,294 AAR Corp. 2,929 $ 55,065 Motorcar Parts of America, Inc.(1) 1,400 21,784 Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc.(1) 6,371 254,139 Standard Motor Products, Inc. 1,855 82,826 AeroVironment, Inc.(1) 1,860 111,619 Stoneridge, Inc.(1) 2,174 39,936 Astronics Corp.(1) 2,153 16,621 Tenneco, Inc., Class A(1)(2) 4,240 29,426 Cubic Corp. 2,731 158,862 Visteon Corp.(1) 2,454 169,866 Ducommun, Inc.(1) 914 30,089 VOXX International Corp.(1) 1,752 13,473 Kaman Corp. 2,432 94,775 Workhorse Group, Inc.(1)(2) 8,033 203,074 Kratos Defense & Security Solutions, Inc.(1) 10,345 199,452 XPEL, Inc.(1) 1,474 38,442 (1) Maxar Technologies, Inc. 5,309 132,406 $2,100,455 Moog, Inc., Class A 2,535 161,049 Automobiles — 0.1% National Presto Industries, Inc. 420 34,381 PAE, Inc.(1) 5,218 44,353 Winnebago Industries, Inc. 2,733 $ 141,214 Park Aerospace Corp. 1,804 19,700 $ 141,214 Parsons Corp.(1) 1,992 66,812 Banks — 6.8% Triumph Group, Inc. 4,259 27,726 (1) Vectrus, Inc. 987 37,506 1st Constitution Bancorp 623 $ 7,414 $ 1,444,555 1st Source Corp. 1,262 38,920 Air Freight & Logistics — 0.4% ACNB Corp. -

Shigeru Ban, on Structural Design

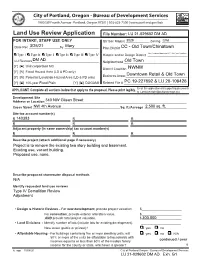

Land Use Review Application File Number: FOR INTAKE, STAFF USE ONLY Qtr Sec Map(s) _____________ Zoning ______________ Date Rec _________________by ___________________ Plan District _____________________________________ Type I Type Ix Type II Type IIx Type III Type IV Historic and/or Design District ______________________ LU Reviews _____________________________________ Neighborhood ___________________________________ [Y] [N] Unincorporated MC District Coalition _________________________________ [Y] [N] Flood Hazard Area (LD & PD only) [Y] [N] Potential Landslide Hazard Area (LD & PD only) Business Assoc __________________________________ [Y] [N] 100-year Flood Plain [Y] [N] DOGAMI Related File # ___________________________________ Email this application and supporting documents APPLICANT: Complete all sections below that apply to the proposal. Please print legibly. to: [email protected] Development Site Address or Location ______________________________________________________________________________ Cross Street ________________________________________________Sq. ft./Acreage _______________________ Site tax account number(s) R R R R R R Adjacent property (in same ownership) tax account number(s) R R R Describe project (attach additional page if necessary) Describe proposed stormwater disposal methods Identify requested land use reviews • Design & Historic Reviews - For new development, provide project valuation. $______________________ For renovation, provide exterior alteration value. $______________________ AND -

Page 1 of 375 6/16/2021 File:///C:/Users/Rtroche

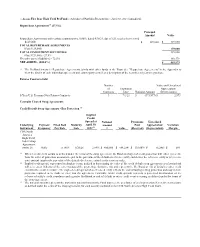

Page 1 of 375 :: Access Flex Bear High Yield ProFund :: Schedule of Portfolio Investments :: April 30, 2021 (unaudited) Repurchase Agreements(a) (27.5%) Principal Amount Value Repurchase Agreements with various counterparties, 0.00%, dated 4/30/21, due 5/3/21, total to be received $129,000. $ 129,000 $ 129,000 TOTAL REPURCHASE AGREEMENTS (Cost $129,000) 129,000 TOTAL INVESTMENT SECURITIES 129,000 (Cost $129,000) - 27.5% Net other assets (liabilities) - 72.5% 340,579 NET ASSETS - (100.0%) $ 469,579 (a) The ProFund invests in Repurchase Agreements jointly with other funds in the Trust. See "Repurchase Agreements" in the Appendix to view the details of each individual agreement and counterparty as well as a description of the securities subject to repurchase. Futures Contracts Sold Number Value and Unrealized of Expiration Appreciation/ Contracts Date Notional Amount (Depreciation) 5-Year U.S. Treasury Note Futures Contracts 3 7/1/21 $ (371,977) $ 2,973 Centrally Cleared Swap Agreements Credit Default Swap Agreements - Buy Protection (1) Implied Credit Spread at Notional Premiums Unrealized Underlying Payment Fixed Deal Maturity April 30, Amount Paid Appreciation/ Variation Instrument Frequency Pay Rate Date 2021(2) (3) Value (Received) (Depreciation) Margin CDX North America High Yield Index Swap Agreement; Series 36 Daily 5 .00% 6/20/26 2.89% $ 450,000 $ (44,254) $ (38,009) $ (6,245) $ 689 (1) When a credit event occurs as defined under the terms of the swap agreement, the Fund as a buyer of credit protection will either (i) receive from the seller of protection an amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity and deliver the reference entity or (ii) receive a net amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity less its recovery value. -

The Regrade, Seattle, WA ABOUT MIDTOWN21

The Regrade, Seattle, WA ABOUT MIDTOWN21 Midtown 21 is a stunning new mixed-use retail and office building designed with beautiful retail space and set in a neighborhood designed for livability. The neighborhood is rapidly evolving and becoming Seattle’s densest and most livable area. With an emphasis on walkability and the ‘live, work, and play’ mindset, the Denny Triangle is a prime target for retailers and restaurants seeking an 18-hour per day customer base. Denny Triangle seamlessly integrates Seattle’s most vibrant neighborhoods as it is at the nexus of the Central Business District, Capitol Hill, South Lake Union and the retail core. Adjacent buildings provide foot traffic from Amazon, HBO, Seattle Children’s, and more. Future adjacent development will include the $1.6B expansion of the Washington State Convention Center, Seattle Children’s Building Cure, as well as Washington’s largest hotel with over 1,200 rooms at 8th and Howell. 5,720 SF of retail divisible 365,000+ SF Class A office Seattle City Light Electrical Substation Nexus 403 units (2019) 1200 Stewart Metropolitan Park 149,309 SF retail Pho Bac MINOR AVE 336,000 SF oce 876 units Market (2019) House Corned Beef Olive Mirabella Retirement Kinects Tower Tower Apartment 366 units (2018) Apt Tilt 49 1901 Minor 307,000 SF oce(2017) + 393 units 737 units (proposed) Convention Convention Center BOREN AVE Hilton Center Expansion Garden Inn Expansion Surface Parking Jars 564,000 sf oce Juice 222 rooms Hill7 (2020) 1800 Terry 270 units (2018) Midtown 21 Building Cure 365,000 SF -

Seattle Children's Research Institute Building

Seattle Children’s Research Institute Building 910 Stewart Street Seattle, WA 98101 Aloha St Valley St Roy St Phase 2 Mercer St Phase 1 Republican St Broad St Harrison St Clay St Thomas St Cedar St John St Vine St DENNY PARK Denny Way Seattle Children’sWall St Research Institute Building Battery St Westlake Ave 8th Ave 7th Ave 6th Ave 5th Ave Denny Way Bell St 4th Ave 3rd Ave 2nd Ave 1st Ave 20 8th & Blanchard St 19 Lenora Westlake Ave Lenora St 14 Midtown 21 SITE Virginia St Hyatt Regency8th & Howell Stewart St Olive Way Way Stewart St 400 units 2ND & PINE 400 Units Pine St CENTURY SQUARE 4th Ave Pike St 1st Ave 2nd Ave 2ND 3rd Ave 5th Ave & PIKE 6th Ave 7th Ave Katie Parsons339 units Maria Royer This electronic mail transmission may contain legally privileged, confidential information belonging to the sender. The 206-456-9471 office 206-264-0630 office information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity named above. If you are not the intended recipient, you are 425-736-5262 cell 206-619-0131 cell hereby notified that any disclosure, copying, distribution or taking any action based on the contents of this electronic mail is [email protected] [email protected] GREEN strictly prohibited. If you have received this electronic mail in error, please contact sender and delete all copies. BUILDING CITY CENTRE Union St RAINIER TWO UNION SQUARE SQUARE EXPANSION BENAROYA HALL RUSSELL MUSEUM SEATTLE ART SEATTLE INVESTMENT ONE UNION SQUARE University St Seneca St Nexus 403 units (2019) 1200 Stewart 149,309 SF retail -

BUILDING CURE 1920 Terry Avenue Seattle, Washington BUILDING CURE

BUILDING CURE 1920 Terry Avenue Seattle, Washington BUILDING CURE Together, Seattle Children’s Hospital seizes this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to build a place where childhood disease can be cured. Located at Stewart Street and Terry Avenue in downtown Seattle, Building SOUTH Cure will expand the Seattle Children’s SITE CAPITOL HILL Research Institute campus to help LAKE accomplish more life-changing research that transforms the lives of Expansion UNION Opening 2020 children and their families. Building Cure will be 13-stories and include research facilities, building operations, a museum and forum space, classrooms, parking for about 300 RETAIL CORE vehicles and ground-oor retail. CBD Pike Place Market PIONEER SQUARE HOTEL ROOMS RESIDENTS 10M 14M PIKE PLACE 22M+ SQ FT OF NEW MARKET VISITORS ANNUAL VISITORS OFFICE SPACE ANNUALLY (Developed or Planned) 613K IN PRIMARY NEW PROJECTS TRADE AREA 14K+ P CURRENT 34K+ 265K $459M NEW RESIDENT UNITS $1.46B DAYTIME 6K+ DOWNTOWN 98K ANNUAL BUSINESS (Developed or Planned) POPULATION NEW ROOMS SEATTLE RETAIL PARKING SPACES REVENUE FROM (Developed or Planned) SALES (2015) CRUISE INDUSTRY DOWNTOWN SEATTLE Seattle City Light Electrical Substation Nexus 403 units (2019) 1200 Stewart Metropolitan Park 149,309 SF retail Pho Bac MINOR AVE 336,000 SF oce 876 units Market (2019) House Corned Beef Olive Mirabella Retirement Kinects Tower Tower Apartment 366 units (2018) Apt Tilt 49 1901 Minor 307,000 SF oce(2017) + 393 units 737 units (proposed) Convention Convention Center BOREN AVE Hilton Center Expansion -

1200 Howell St

1200 HOWELL ST EARLY DESIGN GUIDANCE DOWNTOWN DESIGN REVIEW BOARD MEETING ON 12/1/2015 DPD #3021813 CONTENTS URBAN FRAMEWORK Project Information and Neighborhood ............................................................................... 4 Zoning Summary / Zoning Map .......................................................................................... 6 Project Vicinity Building Use and City Context .................................................................... 8 Transportation and Street Level Analysis Maps .................................................................. 10 Surrounding Projects ....................................................................................................... 12 Neighboring Projects ....................................................................................................... 16 Site Details / Survey ....................................................................................................... 19 Climate Analysis and Solar Orientation ............................................................................ 20 Street Elevations and Photos ............................................................................................ 22 MASSING OPTIONS Option 1 .......................................................................................................................... 28 Option 2 .......................................................................................................................... 32 Option 3 (Preferred) ....................................................................................................... -

Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Annual Report December 31

Annual Report | December 31, 2020 Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Contents Your Fund’s Performance at a Glance .................1 About Your Fund’s Expenses ..........................2 Performance Summary ...............................4 Financial Statements .................................8 Please note: The opinions expressed in this report are just that—informed opinions. They should not be considered promises or advice. Also, please keep in mind that the information and opinions cover the period through the date on the front of this report. Of course, the risks of investing in your fund are spelled out in the prospectus. Your Fund’s Performance at a Glance • For the 12 months ended December 31, 2020, Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund returned about 21% for each of its share classes. • The period was marked by the global spread of COVID-19 and efforts to contain it. Responses from policymakers, the creation and initial distribution of vaccines, and the easing of some restrictions soon lifted investor sentiment, and stock markets hit highs in December. After an initial period of high volatility and low liquidity in the bond markets, yields fell and prices rose amid unprecedented actions taken by governments and central banks to blunt the virus’s economic impact. • The fund, which offers investors exposure to every segment, size, and style of the U.S. equity market, closely tracked its target index, the CRSP US Total Market Index. • The technology and consumer discretionary sectors provided the largest contributions to the fund’s performance. Financials and energy were the biggest detractors. Market Barometer Average Annual Total Returns Periods Ended December 31, 2020 One Year Three Years Five Years Stocks Russell 1000 Index (Large-caps) 20.96% 14.82% 15.60% Russell 2000 Index (Small-caps) 19.96 10.25 13.26 Russell 3000 Index (Broad U.S.