Philanthropy at the Chautauqua Institution By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chautauqua Institution

Chautauqua Institution John Q. Barrett* Copyright © 2011 by John Q. Barrett. All rights reserved. Chautauqua Institution is a beautiful lakeside Victorian village/campus located in the southwestern corner of New York State. During its summer season, Chautauqua is the site of intellectual and cultural programming, study, performance and recreation of all types. Many prominent Americans and others in every field of endeavor have appeared before Chautauqua’s special audiences in its gorgeous venues. Robert H. Jackson’s connections to Chautauqua Institution were many faceted. It is located very near Jamestown, New York, which was Jackson’s hometown from late boyhood forward. For almost fifty years, Chautauqua was a major part of Jackson’s expanding horizons, intellectual development, study and leisure—it was one of the places he loved best, and it deserves much credit for making him what he became (as he does for advancing it). Robert Jackson was attending Chautauqua Institution programs at least by 1907 (age 15), when he got to spend much of a day there in the group that was hosting speaker William Jennings Bryan. Jackson began his own Chautauqua speaking career at least by 1917, when he was 24. In 1936, Jackson was at President Franklin Roosevelt’s side when he delivered at Chautauqua his famous “I Hate War” speech. Jackson’s own Chautauqua platform appearances included his highly-publicized July 4, 1947, speech about the just-completed Nuremberg trial and its teachings, including about the prospects for world peace in that time of spreading cold war and global tension. On October 13, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren * Professor of Law, St. -

Lake Junaluska- Heir of Camp Meeting and Chautauqua by T

Lake Junaluska- Heir of Camp Meeting and Chautauqua By T. Otto Nall * N OBSERVER trying to describe his first visit to a youth as- sembly, with its classes, morning watch, campfire service, stunt night, and treasure hunt, said, "It's a combination of college, circus and camp meeting." Today's summer assembly demands a different figure of speech. The assembly owes much to two factors in history-the camp meet- ing and the chautauqua. Some of the best characteristics of both have survived in the assembly, even though more than 100 oamp meetings are still drlawing crowds and the year's program at Lake Chautauqua, New York is as well filled as ever. The camp meeting movement thlat flourished in frontier days has been misunderstood. In the early stages, these meetings were bois- terous; they were often accompanied by disorderliness, irregular- ities, and hysteria. But within a few years camp meetings became wlell planned and orderly institutions. Charles A. Johnson, writing on "The Frontier Camp Meeting" in The Mississippi Valley His- torical Review, says: "On successive frontiers it passed through a boisterous youth, characterized by a lack of planning, extreme disorder, high-tension emotionalism, bodily excitement, and some immorality; it then moved to a more formalized stage distinguished by its planning, more effective audience management, and notable decline in excess- ive emotionalism. In this institutional phase thle meetings were smaller in size, and highly systematized as to frequency, length, pro- cedure of service, and location." Some of the emotionalism was no doubt due to the conditions of frontier living-the caprices of the weather, the danger of attacks by unfriendly Indians, the scourge of starvation, the threat of illness without benefit of medic'al aid, and sheer loneliness. -

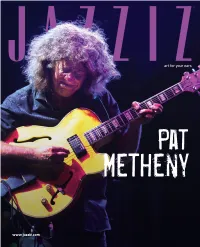

JAZZIZ-Metheny-Interviews.Pdf

Pat Metheny www.jazziz.com JAZZIZ Subscription Ad Lage.pdf 1 3/21/18 10:32 AM Pat Metheny Covered Though I was a Pat Metheny fan for nearly a decade before I special edition, so go ahead and make fun if you please). launched JAZZIZ in 1983, it was his concert, at an outdoor band In 1985, we published a cover story that included Metheny, shell on the University of Florida campus, less than a year but the feature was about the growing use of guitar synthesizers before, that got me to focus on the magazine’s mission. in jazz, and we ran a photo of John McLaughlin on the cover. As a music reviewer for several publications in the late Strike two. The first JAZZIZ cover that featured Pat ran a few ’70s and early ’80s, I was in touch with ECM, the label for years later, when he recorded Song X with Ornette Coleman. whom Metheny recorded. It was ECM that sent me the press When the time came to design the cover, only photos of Metheny credentials that allowed me to go backstage to interview alone worked, and Pat was unhappy with that because he felt Metheny after the show. By then, Metheny had recorded Ornette should have shared the spotlight. Strike three. C around 10 LPs with various instrumental lineups: solo guitar, A few years later, I commissioned Rolling Stone M duo work with Lyles Mays on the chart-topping As Wichita Fall, photographer Deborah Feingold to do a Metheny shoot for a Y So Falls Wichita Falls, trio, larger ensembles and of course his Pat cover story that would delve into his latest album at the time. -

The Chautauqua Lake Camp Meeting and the Chautauqua Institution Leslie Allen Buhite

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 The Chautauqua Lake Camp Meeting and the Chautauqua Institution Leslie Allen Buhite Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE THE CHAUTAUQUA LAKE CAMP MEETING AND THE CHAUTAUQUA INSTITUTION By LESLIE ALLEN BUHITE A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Leslie Allen Buhite defended on April 17, 2007. Carrie Sandahl Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd Outside Committee Member Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member Approved: C. Cameron Jackson, Director, School of Theatre Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre & Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved of the above named committee members. ii For Michelle and Ashera Donald and Nancy Mudge Harold and Ruth Buhite As a foundation left to create the spiral aim A Movement regained and regarded both the same All complete in the sight of seeds of life with you -- Jon Anderson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My very special thanks and profound gratitude to Dr. Carrie Sandahl, whose unrelenting support and encouragement in the face of my procrastination and truculence made this document possible. My thanks and gratitude also to committee members Dr. Donna Marie Nudd and Dr. Mary Karen Dahl for their patient reading and kind and insightful criticism. Of my acquaintances at Florida State University, I also extend my appreciation to Dr. -

Osobnosť Pata Methenyho

JANÁČKOVA AKADÉMIA MÚZICKÝCH UMENÍ V BRNE HUDOBNÁ FAKULTA Katedra jazzovej interpretácie Jazzová interpretácia Osobnosť Pata Methenyho Bakalárska práca Autor práce: Samuel Marinčák Vedúci práce: MgA. Vilém Spilka Oponent práce: MgA. Jan Dalecký Brno 2014 Bibliografický záznam MARINČÁK, Samuel. Osobnosť Pata Methenyho /Personality of Pat Metheny/ Brno : Janáčkova akadémia múzických umení v Brne, Hudobná fakulta, Katedra jazzovej interpretácie, 2014, 36 s, vedúci práce : MgA. Vilém Spilka Anotácia Bakalárska práca je zameraná na osobnosť jednej z najväčších postáv vo svete jazzu v súčasnosti. Ponúka zaujímavé informácie o jeho živote, kariére, diskografii a o mnohých iných aspektoch súvisiacich s ním. Kľúčové slová jazz, improvizácia, biografia, diskografia, ocenenia, zvuk Annotation This bachelor thesis is focused on the life and work of one of the greatest artists in the world of jazz. It will offer you a very interesting insight to his life, career, discography and other aspects connected to him. Key Words jazz, improvisation, biography, discography, awards, sound Prehlásenie: Prehlasujem, že som predloženú prácu spracoval samostatne, s použitím uvedených zdrojov a prameňov. Zároveň dávam zvolenie k tomu, aby táto práca bola umiestnená v Knižnici JAMU a slúžila na študijné účely. V Brne, dňa 28.7.2014 Samuel Marinčák Poďakovanie: Na tomto mieste by som sa rád poďakoval vedúcemu mojej práce MgA. Vilémovi Spilkovi a oponentovi MgA. Janovi Daleckému, ktorí ma pri písaní usmerňovali a ponúkli mi cenné rady. Obsah Úvod ............................................................................................................................ -

DISCOGRAFIA BASICA DEL JAZZ Prof.: Willie Campins

DISCOGRAFIA BASICA DEL JAZZ Prof.: Willie Campins ESTILO DE NUEVA ORLEANS O HOT JAZZ: Original Dixieland Jazz Band: • Sensation! (ASV AJA 5023R)(1920) • The Original Dixieland Jazz Band 1917-1921 (Timeless CBC 1-009) New Orleans Rhythm Kings: • The New Orleans Rhythm Kings and Jelly Roll Morton (Milestone MCD 47020-2) (1922- 1925) Jelly Roll Morton: • Jelly Roll Morton 1923-1924 (Classics 584) • The Complete Jelly Roll Morton 1926-1930 (RCA Bluebird ND82361) • Jelly Roll Morton Vol. 1 (JSP CD 321) (1926/1927) King Oliver: • King Oliver Vol. 1 1923-1929 (con Louis Armstrong) (CDS RPCD 607) • King Oliver 1923 (con Louis Armstrong) (Classics 650) Sidney Bechet: • The Legendary Sidney Bechet (Bluebird ND 86590) • New Orleans Jazz (Columbia 462954) Kid Ory: • Kid Ory’s Creole Jazz Band (Good Time Jazz 12022) ESTILO DE CHICAGO O JAZZ TRADICIONAL: Louis Armstrong: • Con King Oliver: King Oliver Vol. 1 (1923-1929) • Hot Fives and Sevens Vol. 1 (JSP 312) (1925/26), Vol. 2 (JSP 313) (1927), Vol. 3 (JSP 314) (1929) • Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra (1929-1932) (Classics 570, 557, 547 y 536) • Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra (1932-1939) (Classics 529, 509, 512, 515, 523) Bix Beiderbecke: • Bix’n’Bing (Con Bing Crosby) (ASV AJA 5005) • Bix Beiderbecke Vol. 1 Singin’ the Blues (Columbia 4663092) (1927) • Bix Beiderbecke Vol. 2 At the Jazz Band Ball (Columbia 4608252) (1928) Eddie Condon: • Dixieland All Stars (MCA GRP 16372) (1939-1946) Fletcher Henderson: • Fletcher Henderson 1924-1925 (Classics 633) SWING: Duke Ellington: • The Complete Brunswick Recordings Vol. 1 y 2 (MCA MCAD 42325 y 42348) (1927-1931) • Early Ellington 1927-1934 (RCA Buebird 86852) • Rockin’ In Rhythm (ASV AJA 5057) (1927-1936) • Black, Brown and Beige (RCA Bluebird 86641) (1944-1946) Benny Goodman: • The Birth of Swing (RCA Bluebird ND 90601) (1935-1936) • Stompin’ at the Savoy (RCA Bluebird ND 90631) (1935-1938) • After You’ve Gone (RCA Bluebird ND 85631) (1935-1937) • Live at Carnegie Hall (Columbia 4509832) (1938) • Sextet Featuring Charlie Christian (Columbia 4656792) (1939-1941) • B.G. -

A Moment in Railroad History Theodore Roosevelt's Presidential Special to Chautauqua in 1905 © 2013 by Richard F

A Moment in Railroad History Theodore Roosevelt's Presidential Special to Chautauqua in 1905 © 2013 By Richard F. Palmer The operation of special trains carrying presidents and VIP's has always been a challenge to railroad management since the early days of railroading. In most cases, however, we know little or nothing about this topic, other than what might be gleaned from old newspaper accounts or reminiscences. The Erie Railroad had more than its share of traveling dignitaries over the years, starting with orator Daniel Webster's and President Millard Fillmore's famous trip over the newly completed line from Piermont to Dunkirk in May, 1851. This story is based on an official memo issued by the Erie Railroad of the "Chautauqua Special" from Waverly to Lakewood, N.Y. on August 10, 1905. It was given to the author by the late Lyall Squair (cq) of Syracuse, N.Y., a recognized authority on the life of Theodore Roosevelt and an avid collector of Roosevelt memorabilia. In the early 1960s Mr. Squair, an archivist at Syracuse University, was cataloging the records of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western that had been donated by the Erie-Lackawanna. Among these records was an old fashioned traveling trunk labeled "Erie Museum Collection." The account of Roosevelt's trip was among these papers. Throughout his political career as well as in private life, Roosevelt traveled extensively by rail across the country. The special train originated in Jersey City and ran over the Lehigh Valley to Waverly, N.Y., a distance of 273 miles; then another 197 miles over the Erie to Lakewood, N.Y., the station for the Chautauqua Institution. -

The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Culture as Entertainment: The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924 Full Citation: James P Eckman, “Culture as Entertainment: The Circuit Chautauqua in Nebraska, 1904-1924,” Nebraska History 75 (1994): 244-253 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1994Chautauqua.pdf Date: 8/09/2013 Article Summary: At first independent Chautauqua assemblies provided instruction. The later summer circuit Chautauquas sought primarily to entertain their audiences. Cataloging Information: Names: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Keith Vawter, Russell H Conwell, William Jennings Bryan, Billy Sunday Sites of Nebraska Chautauquas: Kimball, Alma, Homer, Kearney, Pierce, Fremont, Grand Island, Lincoln, Fullerton Keywords: lyceum, Redpath Bureau, Keith Vawter, contract guarantee, “tight booking,” Nebraska Epworth Assembly (Lincoln), Chautauqua Park Association (Fullerton), -

THE EMERGENCE of CHAUTAUQUA AS a RELIGIOUS and EDUCAT10NAL INSTITUTION., 187'4-1900 Es M James H

r. THE EMERGENCE OF CHAUTAUQUA AS A RELIGIOUS AND EDUCAT10NAL INSTITUTION., 187'4-1900 es m James H. McBath ty . exclaim~d st "This place is simply marvellous," Edward Evere'h -Hale of when 'he first visited the Chautauqua Assembly in 1880. "It is a great a, ' college for the middle classes. "1 The opinion was shared by thous~nds who made the trek to Lake Chautauqua in the New York State. Within two years after the opening of the first Assembly, representatives from e. twen'ty-sevenstates, and England and Canada, were present for the ty :SllDuner -activities. 2 Before the end of the century, with visitors from every lh part of the country, Chautauqua liked to call itself "the most national ,st place in the United States. "-3 'The iqstitutiQn that impressed Hale had evolved from a small $und'ay school enCamprnent near Jamestown, N-ew York•. Chautauqua ce was founded in 1874 by John Heyl Vincent, editor of.the Sunday School Journalandoth~r m Methodist Sunday-school periodicals, and latera Meth~lst m Methodist bishop, and Lewis Miller, a businessman and layman. Both :men had particuJar inj;eFest in the advanced t,ta'Uiihg of . SUnday-school workers which they decided to pursue throUgh .-~ ..shott: , .~ .i outdoor summer assemhly.VincentrecaUed: of :,\ "'1" Formahy yea.rs whileih the pastorat~and in. my speCial. efforts lbCtea(e'a m :r' L~ general .interest ,in the training. of ,Sunday .school tea.chers and oUicerslheld in all ~e !! " . • .: parts of the country iAstitutesandno....fua'lclasses after the .general plan of secular \18 , ,l educators. -

The First Chautauqua Assembly in 1874 Are Scarce

25 5 BY JONATHAN D. SCHMITZ In southwestern New York State at a Methodist camp meeting ground, two men began the adult education movement that enriched and benefited millions of Americans well into the twentieth––and twenty-first––centuries. CHAUTAUQUA INSTITUTION unday schools of the nineteenth century taught more than religion; for many American children, these “Sabbath schools” provided their only general education in reading, writing, arithmetic, and social manners. Although Sunday schools declined in the years following the Civil War, starting in 1865 the Methodist Church began to restructure the curriculum, and Reverend John Heyl Vincent, corresponding secretary for the Sunday School Union and editor of several related journals, planned to hold two-week normal school ses- sions to teach this new curriculum. Left and above: Nineteenth-century postcards advertised Chautauqua as a tourist destination. www.nysarchivestrust.org 26 York State. Chautauqua Lake advertise the Assembly was rapidly becoming a popu- throughout America. Well- lar tourist destination after known Christian journalist T. the introduction of railroads, De Witt Talmage heartily and both Vincent and Miller recommended attendance via realized that this location a Biblical analogy: would allow them to bring in Reverend Doctor J.H. audiences and speakers from Vincent, the silver-tongued across the country to make trumpet of Sabbath- the “New York Chautauqua Schoolism, is marshalling Assembly” a national event. a meeting for the banks Miller was elected president of the Chautauqua Lake of the Assembly’s organizing which will probably be committee and took on the task the grandest religious NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY of preparing Chautauqua’s pic-nic ever held since the grounds, which were typical of five thousand sat down a camp meeting. -

Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle

LiteraryChautauqua & Scientific Circle Founded in Chautauqua, New York, 1878 Book List 1878 – 2018 A Brief History of the CLSC “Education, once These are the words of Bishop John Heyl Vincent, cofounder the peculiar with Lewis Miller of the Chautauqua Institution. They are privilege of the from the opening paragraphs of his book, The Chautauquan few, must in Movement, and represent an ideal he had for Chautauqua. To our best earthly further this Chautauquan ideal and to disseminate it beyond estate become the physical confines of the Bishop John Heyl Vincent Chautauqua Institution, Bishop the valued Vincent conceived the idea of possession of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC), and founded it in 1878, four years after the founding of the the many.” Chautauqua Institution. At its inception, the CLSC was basically a four year course of required reading. The original aims of the CLSC were twofold: To promote habits of reading and study in nature, art, science, and in secular and sacred literature and To encourage individual study, to open the college world to persons unable to attend higher institution of learning. On August 10, 1878, Dr. Vincent announced the organization of the CLSC to an enthusiastic Chautauqua audience. Over 8,400 people enrolled the first year. Of those original enrollees, 1,718 successfully completed the reading course, the required examinations and received their diplomas on the first CLSC Recognition Day in 1882. The idea spreads and reading circles form. As the summer session closed in 1878, Chautauquans returned to their homes and involved themselves there in the CLSC reading program. -

Late Night Jazz: Die Multiplen Sounds Des Pat Metheny 10.10.20, 22:06-24:00 Uhr

Late Night Jazz: Die multiplen Sounds des Pat Metheny 10.10.20, 22:06-24:00 Uhr Angefangen hat er mit Sound-betontem Fusion-Jazz, aber seine Erkundungsreise mit der Gitarre hat Pat Metheny zu den verschiedensten Stilen geführt. Zudem auch noch zu vielen unterschiedlichen Gitarren. Bis zu 24 Saiten bespielt er und lässt auch die Elektronik nicht aus. Ein Multitalent der Saiten und Stile - einer der einflussreichsten Musiker der letzten Jahrzehnte im Jazz. Nicht umsonst heisst eine ganze Gitarren-Serie von Ibanez nach ihm - PM. Zwei Stunden in Gesellschaft eines neugierigen Sound- Magiers. Redaktion und Moderation: Andreas Müller-Crepon Titel Interpret*in Komponist*in CD-Titel / Label Never Too Far Away Pat Metheny, Dave Holland, Roy Pat Metheny Question & Answer / Geffen Records Haynes American Garage Pat Metheny Group Pat Metheny American Garage / ECM The Sound of Water Pat Metheny Pat Metheny Metheny/Mehlday Quartet / Nonesuch Nothing Personal Michael Brecker Don Grolnick Michael Brecker: Sea Glass / MCA Impulse Nacada Pat Metheny Pat Metheny Pat Metheny: Live 1976 / Digital Legacy Sky and Sea (Blue in Cassandra Wilson Miles Davis Traveling Miles / Blue Note Green) Have You Heard? Pat Metheny Group Pat Metheny Pat Metheny Group: The Road to You – Live in Europe / Geffen Records Noche de Ronda Charlie Haden Maria Teresa Lara Charlie Haden: Nocturne / Universal Don’t Forget Jim Hall & Pat Metheny Pat Metheny Jim Hall & Pat Metheny / Telarc Wildwood Flower Charlie Haden Family & Friends Alvin Pleasant Carter Charlie Haden Family & Friends: