Pat Metheny Plays the Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

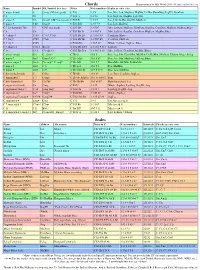

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/Wideworld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105 ETF 46 56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 46 J Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/WideWorld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47 thethe by Kent S. Markle RedRed HotHot BluesBlues AZZ MUSIC HAS OFTEN BEEN CALLED THE ONLY ART FORM J to originate in the United States, yet blues music arose right beside jazz. In fact, the two styles have many parallels. Both were created by African- Americans in the southern United States in the latter part of the 19th century and spread from there in the early decades of the 20th century; both contain the sad sounding “blue note,” which is the bending of a particular note a quar- ter or half tone; and both feature syncopation and improvisation. Blues and jazz have had huge influences on American popular music. In fact, many key elements we hear in pop, soul, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll (opposite) Dinah Washington have their beginnings in blues music. A careful study of the blues can contribute © AP/WideWorld Photos to a greater understanding of these other musical genres. Though never the Born in 1924 as Ruth Lee Jones, she took the stage name Dinah Washington and was later known leader in music sales, blues music has retained a significant presence, not only in as the “Queen of the Blues.” She began with singing gospel music concerts and festivals throughout the United States but also in our daily lives. in Chicago and was later famous for her ability to sing any style Nowadays, we can hear the sound of the blues in unexpected places, from the music with a brilliant sense of tim- ing and drama and perfect enun- warm warble of an amplified harmonica on a television commercial to the sad ciation. -

The Blues Blue

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 56 A grammatical Conundrum the blues Using “blue” and “the blues” Glossary to denote sadness is not recent BACKBEAT—a rhythmic emphasis on the second and fourth beats of a measure. English slang. The word blue BAR—a musical measure, which is a repeated rhythmic pattern of several beats, usually four quarter notes (4/4) for the blues. The blues usually has twelve bars per was associated with sadness verse. and melancholia in Eliza- BLUE NOTE—the slight lowering downward, usually of the third or seventh notes, of a major scale. Some blues musicians, especially singers, guitarists and bethan England. The Ameri- harmonica players, bend notes upward to reach the blue note. can writer Washington Irving CHOPS—the various patterns that a musician plays, including basic scales. When blues musicians get together for jam sessions, players of the same instrument used the term the blues in sometimes engage in musical duels in front of a rhythm section to see who has the “hottest chops” (plays best). 1807. Grammatically speak- CHORD—a combination of notes played at the same time. ing, however, the term the CHORD PROGRESSION—the use of a series of chords over a song verse that is repeated for each verse. blues is a conundrum: should FIELD HOLLERS—songs that African-Americans sang as they worked, first as it be treated grammatically slaves, then as freed laborers, in which the workers would sing a phrase in response to a line sung by the song leader. as a singular or plural noun? GOSPEL MUSIC—a style of religious music heard in some black churches that The Merriam-Webster una- contains call-and-response arrangements similar to field hollers. -

«An Evening with Pat Metheny» Feat. Antonio Sánchez, Linda May Han Oh & Gwilym Simcock

2017 20:00 24.10.Grand Auditorium Mardi / Dienstag / Tuesday Jazz & beyond «An evening with Pat Metheny» feat. Antonio Sánchez, Linda May Han Oh & Gwilym Simcock Pat Metheny guitar Antonio Sánchez drums Linda May Han Oh bass Gwilym Simcock piano Pat Metheny photo: Jimmy Katz Pat Metheny, au-delà de la guitare Vincent Cotro « J’ai atteint un point où j’ai tant composé que tout n’est qu’une grande composition. Avec Antonio, Lina et Gwilym, nous allons explorer cette composition pour en faire, je l’espère, quelque chose de vraiment grandiose ». Pat Metheny, présentation du concert lors du festival Jazz sous les Pommiers, mai 2017 Né en 1954 dans le Missouri, Patrick Bruce Metheny découvre à onze ans Miles Davis puis Ornette Coleman et commence la guitare à douze ans, après s’être essayé à la trompette et au cor. Il écoutera et décortiquera les solos de Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell ou Jim Hall et se produira dès quinze ans avec les meilleurs musiciens dans les clubs de Kansas City. Alors qu’il se passionne pour John Coltrane et Clifford Brown, il rencontre Gary Burton en 1974, année de son explosion sur la scène internationale. Aux côtés du vibraphoniste, il développe ce qui deviendra sa caractéristique : une articulation plutôt relâchée et flexible habituellement observée chez les « souffleurs », combinée à une sensibilité harmonique et rythmique très développée. Son premier disque avec Jaco Pastorius et Bob Moses en 1976, « Bright Size Life », réinvente en quelque sorte la tradition sous des apparences de modernité, pour une nouvelle génération de guitaristes. On voit apparaître sa passion pour la musique d’Ornette Coleman qui se manifestera largement ensuite et jusqu’à aujourd’hui. -

Katherine Riddle

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS Katherine Riddle Soprano “My Life’s Delight” Andrew Welch, piano Carley DeFranco, soprano Ryan Burke, tenor Sunday, March 3, 2013 at 5:00 p.m. Abramson Family Recital Hall Katzen Arts Center American University This senior recital program is in partial fulfillment of the degree program Bachelor of Arts in Music, Vocal Performance and the American University Honors Capstone Program. Ms. Riddle is a student of Dr. Linda Allison. THANK YOU… ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER ( b. 1948 ) wrote the music for the longest running show on Broadway, The Phantom of …to all of the faculty and staff in the music and theatre departments the Opera. This musical is based on a French novel Le Fantôme de that have supported, mentored and encouraged me. Thank l'Opéra by Gaston Leroux. The plot centers around the beautiful soprano, you for pushing me to strive for greatness and helping me to grow as a Christine, who becomes the object of the Phantom’s affections. As the prima person and as a performer. donna, Carlotta, is rehearsing for a performance, a backdrop collapses on her without warning. Carlotta storms offstage, refusing to perform and Christine is tentatively chosen to take her place in the opera that night. She is …to my wonderful friends who are always there for me to cheer, to cry, ready for the challenge. to cuddle or to celebrate. You guys are irreplaceable! Think of Me …to my amazing family (especially my incredible parents) for always Think of me, think of me fondly when we’ve said goodbye being my cheerleaders, giving me their undying love and support and, Remember me, every so often, promise me you’ll try most of all, for helping me pursue my dream. -

Beginning Jazz Guitar Ebook Free Download

BEGINNING JAZZ GUITAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jody Fisher | 96 pages | 01 Jul 1995 | Alfred Publishing Co Inc.,U.S. | 9780739001103 | English | United States Beginning Jazz Guitar PDF Book Image 1 of 4. Having started out as a classical player and now dabbling in other styles like jazz, my eyes have really opened to the amazing possibilities that improvisation can bring. We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits. Download Jam Track Jam Track. Laurence says:. Additional Information. Chuck Johnson on November 16, at am. I would really appreciate your feedback, so do let me know what you think about this post by leaving a comment below. Advertisement - Continue Reading Below. This goes for all the chords. In this guitar lesson, you will learn 6 variations of the jazz blues progression going from the basic blues to more modern variations like the bebop blues. Thank you. A famous jazz musician once said 'jazz can be taught in just three lessons; 1st lesson: practice for 10 years; 2nd lesson: practice and perform for 10 years; 3rd lesson: practice, perform and develop your art for 10 years. The fifth and last element is the improvisation. My pleasure Donald, thanks for reading : Reply. Also has a quite good acoustic amp setting for acoustic guitars with pickup — very versatile amp with a great sound. Added to cart. Although music theory has a bit of a bad reputation, it can make your life as an improvising guitarist a lot easier. So a major the 7th note of the major scale is added to the major chord. -

Jazz Harmony Iii

MU 3323 JAZZ HARMONY III Chord Scales US Army Element, School of Music NAB Little Creek, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170 13 Credit Hours Edition Code 8 Edition Date: March 1988 SUBCOURSE INTRODUCTION This subcourse will enable you to identify and construct chord scales. This subcourse will also enable you to apply chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in harmonic progressions. Unless otherwise stated, the masculine gender of singular is used to refer to both men and women. Prerequisites for this course include: Chapter 2, TC 12-41, Basic Music (Fundamental Notation). A knowledge of key signatures. A knowledge of intervals. A knowledge of chord symbols. A knowledge of chord progressions. NOTE: You can take subcourses MU 1300, Scales and Key Signatures; MU 1305, Intervals and Triads; MU 3320, Jazz Harmony I (Chord Symbols/Extensions); and MU 3322, Jazz Harmony II (Chord Progression) to obtain the prerequisite knowledge to complete this subcourse. You can also read TC 12-42, Harmony to obtain knowledge about traditional chord progression. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES MU 3323 1 ACTION: You will identify and write scales and modes, identify and write chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in a harmonic progression, and identify and write chord scales that correspond to triads, extended chords and altered chords. CONDITION: Given the information in this subcourse, STANDARD: To demonstrate competency of this task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. MU 3323 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Subcourse Introduction Administrative Instructions Grading and Certification Instructions L esson 1: Sc ales and Modes P art A O verview P art B M ajor and Minor Scales P art C M odal Scales P art D O ther Scales Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 2: R elating Chord Scales to Basic Four Note Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 3: R elating Chord Scales to Triads, Extended Chords, and Altered Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback Examination MU 3323 3 ADMINISTRATIVE INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays Dienstag, 19. November 2013, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 23. November 2013, 22.00 - 24.00 Uhr (Zweitsendung) Ohne ihn wäre der Gitarrist Pat Metheny nicht, was er heute ist: Lyle Mays ist seit den Anfängen der Pat Metheny Group mit dabei, ist Ko-Autor der allermeisten Stücke dieser weltberühmten Fusion-Band und nie richtig aus dem Schatten von Strahlemann Metheny herausgekommen. Wer je von der Pat Metheny Group gehört hat, der kennt Lyle Mays: der Pianist, Keyboarder und Komponist ist die rechte Hand von Pat Metheny. Er hat praktisch alle wichtigen Stücke dieser weltberühmten Band mit Metheny zusammen komponiert - und ist dennoch immer im Schatten von Metheny geblieben. Dabei beherrscht Lyle Mays das ganze Spektrum von elektronischen Soundteppichen bis zum makellosen akustischen Piano-Jazz perfekt. Wie ist Lyle Mays zu einem solchen musikalischen Tausendsassa geworden? Und warum wird er als Komponist ständig etwas unterschätzt? Immanuel Brockhaus ist Gast von Jodok Hess. Lab `75: Lab `75 LP NTSU LJ108 Track 2: Ouverture to the Royal Mongolian Suma Foosball Festival Pat Metheny: As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls CD ECM 1190 Track 2: Ozark Pat Metheny Group: Offramp CD ECM 1216 Track 6: James Lyle Mays Trio: Fictionary CD Geffen GED24521 Track 9: Falling Grace Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. 47284 Track 10: Long Life Pat Metheny Group: Speaking Of Now CD Warner Bros 48025 Track 2: Proof Bonustracks – nur in der Samstagsausgabe Pat Metheny Group: Pat Metheny Group CD ECM Track 6: Lone Jack Track 1: San Lorenzo Pat Metheny Group: American Garage CD ECM Track 6: Cross the Heartland Track 4: American Garage Lyle Mays: Street Dreams CD Geffen Records Track 3: Chorinho Track 4: Possible Straight Joni Mitchel: Shadows and Light CD Elektra Track 5: Good Bye Poork-Pie Hat Track 9: Hejira Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. -

Pat Metheny 80/81 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pat Metheny 80/81 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: 80/81 Country: Japan Released: 1980 Style: Post Bop, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1322 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1569 mb WMA version RAR size: 1314 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 404 Other Formats: AU RA MP1 MIDI AHX MOD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Two Folk Songs 1st 1 13:17 Composed By – Pat Metheny 2nd 2 7:31 Composed By – Charlie Haden - 80/81 3 7:28 Composed By – Pat Metheny The Bat 4 5:58 Composed By – Pat Metheny Turnaround 5 7:05 Composed By – Ornette Coleman Open 6 Composed By – Haden*, Redman*, DeJohnette*, Brecker*, Metheny*Composed 14:25 By [Final Theme] – Pat Metheny Pretty Scattered 7 6:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Every Day (I Thank You) 8 13:16 Composed By – Pat Metheny Goin' Ahead 9 3:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Companies, etc. Recorded At – Talent Studio Lacquer Cut At – PRS Hannover Credits Bass – Charlie Haden Design – Barbara Wojirsch Drums – Jack DeJohnette Engineer – Jan Erik Kongshaug Guitar – Pat Metheny Photography By [Back] – Dag Alveng Photography By [Inside] – Rainer Drechsler Producer – Manfred Eicher Tenor Saxophone – Dewey Redman (tracks: B1, B2, C1, C2), Mike Brecker* (tracks: A1, A2, B2, C1, C2, D1) Notes Recorded May 26-29, 1980 at Talent Studios, Oslo. An ECM Production. ℗ 1980 ECM Records GmbH. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 042281557941 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ECM 1180/81, 80/81 (2xLP, ECM Records, ECM 1180/81, Pat Metheny Germany 1980 2641 180 Album) ECM Records -

Rape Data Proves Incorrect

. American Garage -page 9 VOL XIV, NO. 47 an independent student newspaper serving notre dame and saint mary’s THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 8,1979 Rape data proves incorrect By Tom J ackman pattern. Over a period of 11 nine incidents, and that he had Senior Staff Reporter years you can’t really say that pointed out another one that one area stands out.’’ had been left off. Roemer said that “to the best The most notable feature of A map compiled by the Secur of my knowledge it (the map] is the map was its cluster of four ity Department and Dean of accurate, and it was a bonafide incidents on Saint Mary’s Road Students James Roemer that effort on my part.’’ He added, between Holy Cross Hall and pinpoints all reported rape inci “But I can’t give a definitive U.S. Rte. 31, one which occur dents on campus since 1969 Will number, and if we’ve missed a red in 1975, two on the same be re-researched and revised couple we’ll go back to Glenn night exactly two years ago, after The Observer last night (Terry) and research it further. ’ and another last month. verified one of several reported Roemer noted that the first inaccuracies in the map. draft of the map contained only [icontinued on page 4] the map located 10 rapes on campus in the last 11 years. But upon its release to The Observer , several students US government urges claimed the number of incid ents was higher, and one rape Americans to leave Iran victim was contacted last night who verified that her incident The U.S.