(Appearance and Disappearance) of Two Belgian Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agnès Varda in Californialand

Les Plages d’Agnès. L’ADRC CINÉ-TAMARIS hotographe, cinéaste et aujourd’hui en partenariat avec Partiste plasticienne, Agnès Varda est l’AFCAE plurielle, et ne cesse d’apporter un souffle présentent de liberté, de créativité, dans la vie culturelle française. Après une première collaboration en 2013 à l’occasion de la ressortie des films de Jacques Demy, CINÉ-TAMARIS et l’ADRC proposent une rétrospective de 9 films restaurés dans laquelle Agnès vous invite à (re)découvrir la variété de son travail. AGNÈS VARDA Rétrospective 9 films © christophe vallaux © christophe Cléo de 5 à 7 Sans toit ni loi Agnès Varda in Californialand Un film écrit et réalisé par Un film écrit et réalisé par Agnès Varda Agnès Varda Los Angeles, les plages de Venice et de Santa Monica, on les a connues, Jacques (Demy) et moi, à chacun de nos séjours. Fiction de 90 minutes Fiction de 105 minutes Elles ont été nos décors de vie et de films, dont pour moi, un film hippie et un film triste. Une jetée qui s’élance dans le Pacifique en noir et blanc filmée en couleurs, filmée en 1985 À en été 1961 – visa n° 24.864 visa n° 60.033 au bout du bout de la ruée vers l’Ouest. Des pique-niques à la plage. Des rencontres, les jeunes Harrison Ford et Jim Morrison, Produit par Images : Patrick Blossier les Knop and King et Viva! avec un point d’exclamation comme nom d’artiste. Les Black Panthers. Les peintures murales. Georges de Beauregard Son : Jean-Paul Mugel Images : Jean Rabier Décors : Jean Bauer, Son : Jean Labussière Anne Violet Décors : Bernard Evein Musique : Joanna Bruzdowicz -

Mor Chantal Akerman, Figura Clau Del Cinema Experimental Dels Setanta

Cultura i Mitjans | foto_esteveplantada_Esteve Plantada | Actualitzat el 07/10/2015 a les 12:22 Mor Chantal Akerman, figura clau del cinema experimental dels setanta La cineasta belga ha mort a París als 65 anys | El festival de Locarno va viure l'estrena del seu darrer film, "No home movie" Chantal Akerman, en una imatge d'arxiu Chantal Akerman (http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001901) (Brusel·les, 1950) va decidir acabar amb la seva vida a París, la ciutat on residia, aquest darrer dilluns. Tenia 65 anys i era una de les grans figures del cinema experimental dels setanta. Destacada per l'ús de crus i llargs plans seqüència, la cineasta belga va provar de captar les arestes de la condició femenina, lligada a una intensa reflexió sobre la identitat. De fet, la figura de la seva mare (morta el 2014 i present com a reflexió a No home movie) va planar sempre per la seva obra, com a jueva polonesa que va sobreviure a Auschwitz. Deutora de l'art d'avantguarda, les pel·lícules d'Akerman sempre van intentar trencar els preceptes del cinema clàssic, ja fos fent esclatar la linealitat de la narració, qüestionant els propis traumes o seguint la tradició dels particulars retrats cinematogràfics que van practicar autors com Philippe Garrel o Andy Warhol. La seva proposta va viure una època creativa daurada entre els setanta i els vuitanta, alimentada pel contacte que va establir a Nova York amb personalitats com Michael Snow o Jonas Mekas. Una filmografia amb més de 40 títols El seu debut va ser el curtmetratge Saute ma ville (1968), quan només tenia disset anys, el https://www.naciodigital.cat/noticia/96023/mor-chantal-akerman-figura-clau-cinema-experimental-dels-setanta Pagina 1 de 2 preludi d'una obra que, anys després, seguiria mostrant una gran inquietud per no deixar indiferent. -

Female, Feminine Or Feminist

University of Birmingham Feminist phenomenology and the film-world of Agnès Varda Ince, Katherine DOI: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01303.x License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Ince, K 2013, 'Feminist phenomenology and the film-world of Agnès Varda', Hypatia A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 602-617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01303.x Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Ince, K. (2013), Feminist Phenomenology and the Film World of Agnès Varda. Hypatia, 28: 602–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01303.x, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1527- 2001.2012.01303.x. Eligibility for repository : checked 12/09/2014 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Cinema Comparat/Ive Cinema

CINEMA COMPARAT/IVE CINEMA VOLUME IV · No.8 · 2016 Editors: Gonzalo de Lucas (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and Albert Elduque (University of Reading). Associate Editors: Ana Aitana Fernández (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Núria Bou (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Xavier Pérez (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Advisory Board: Dudley Andrew (Yale University, United States), Jordi Balló (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain), Raymond Bellour (Université Sorbonne-Paris III, France), Francisco Javier Benavente (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Nicole Brenez (Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne, France), Maeve Connolly (Dun Laoghaire Institut of Art, Design and Technology, Irleland), Thomas Elsaesser (University of Amsterdam, Netherlands), Gino Frezza (Università de Salerno, Italy), Chris Fujiwara (Edinburgh International Film Festival, United Kingdom), Jane Gaines (Columbia University, United States), Haden Guest (Harvard University, United States), Tom Gunning (University of Chicago, United States), John MacKay (Yale University, United States), Adrian Martin (Monash University, Australia), Cezar Migliorin (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil), Alejandro Montiel (Universitat de València), Meaghan Morris (University of Sidney, Australia and Lignan University, Hong Kong), Raffaelle Pinto (Universitat de Barcelona), Ivan Pintor (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Àngel Quintana (Universitat de Girona, Spain), Joan Ramon Resina (Stanford University, United States), Eduardo A.Russo (Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina), Glòria Salvadó (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Yuri -

No Home Movie

A film by Chantal Akerman NO HOME MOVIE North American Theatrical Premiere New York: Opens April 01, 2016 Los Angeles: Opens April 22, 2016 “It was heartbreaking when I saw it last week and it is devastating now.” –J. Hoberman, The New York Times An Icarus Films Release http://icarusfilms.com/filmmakers/chant.html ABOUT THE FILM Chantal Akerman’s masterful final film is a portrait of her relationship with her mother, Natalia, a Holocaust survivor and central presence her daughter's films. FILM FESTIVALS World Premiere 2015 Locarno Film Festival North American Premiere 2015 Toronto International Film Festival U.S. Premiere 2015 New York Film Festival FILMMAKER’S STATEMENT I’ve been filming just about everywhere for years now, as soon as I see a shot. Not with anything specific in mind, just the feeling that one day, these images will make a film, or an art installation. I just let myself go, because I want to, and instinctively. Without a film script, with no conscious project in view. Three installations have been created from these images and have been shown in many locations (at the Art Film Festival in Belgium, for example, etc.). And I continue to film. Myself. Alone. Last spring, with the help of Claire Atherton and Clémence le Carré, I brought together around 20 hours of images and sounds still not knowing where I was going. Then we started sculpting the material. 20 hours became 8, then 6, and then after a while, 2. And there we saw it, we saw a film and I said to myself: of course, it’s this film that I wanted to make. -

Jan – Mar 2018 V11

Jan – Mar 2018 V11 ∙ 3 MEMBERSHIP “Forward-looking communities strive to hold onto important parts of their past and, if practical, make sensible renovations to bring venerable structures into the future. That’s the case with the newly restored Dundee Theater.” — Omaha World-Herald Editorial, Nov 31, 2017 December was a dream. On the first day of the month, we opened the doors of the renovated Dundee Theater, and, along with our café partners Kitchen Table Members Select Central, welcomed thousands of you back to Omaha’s historic cinema. Thanks to Your voices have been heard! This year’s Members Select winner was described the generosity and efforts of so many, we reached our goal to have the project by Roger Ebert as “a movie with the courage to be about complex, sweeping completed in time to host the Omaha premiere of Film Streams Board Member emotions, and to use the star power of its actors without apology.” Alexander Payne’s latest opus, Downsizing (still showing!). And we’re just getting started. This quarter will bring outstanding new releases from around the world to both of our cinemas, along with annual traditions like Jan 5 – 11 Ruth Sokolof the Oscar Shorts and Film Streams Members Select, our first repertory series (and Courses!) in the Dundee Theater’s Linder Microcinema, and a much- Out of Africa requested return of Midnight Movies to the Dundee. Dir. Sydney Pollack — 1985 — USA 161 min — PG So, join us! The show is just getting started. Meryl Streep, Robert Redford, and cinematographer David Watkin’s sweeping images of the Kenyan plains light up the screen in this sultry drama. -

“Farewell: an Homage to Chantal Akerman”Frieze

FAREWELL Delphine Seyrig in Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, 1975, 35mm film still A N HOMAGE TO CHANTAL A KERMAN 1950— 2015 Akerman_frieze176 V2.indd 112 09/12/2015 12:42 Tributes by The great flmmaker Chantal Akerman James Benning died in October 2015; she was 65. She made Manon de Boer her frst short flm, Saute ma ville (Blow Up Jem Cohen My Town, 1968), when she was just 18. Her frst Tacita Dean feature, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, Chris Dercon 1080 Bruxelles (1975), established her reputation Joanna Hogg & Adam Roberts as a radical, feminist flmmaker. Over the next Sharon Lockhart four decades, in her native Belgium and the US — Rachael Rakes as well as in China, eastern Europe, Israel and Mexico, among other places — Akerman made over 40 documentary and feature flms; she also created installation and video art. The infuence her work has exerted is inestimable. Following her death, the director Todd Haynes dedicated the screening of his latest movie, Carol (2015), to Akerman at the New York Film Festival, stating that ‘as someone thinking about female subjects and how they’re depicted’ her work had changed the ways in which he thought about, and imagined, film. Over the following pages, nine filmmakers, curators and artists refect on what Akerman’s work meant to them. Akerman_frieze176 V2.indd 113 09/12/2015 12:42 M ANON DE B OER JAMES B ENNING An artist based in Brussels, Belgium. A flmmaker living in Val Verde, California, USA. In the week following Akerman’s death, as Chantal Akerman. -

The Magic Mirror” Uncanny Suicides, from Sylvia Plath to Chantal Akerman

“THE MAGIC MIRROR” UNCANNY SUICIDES, FROM SYLVIA PLATH TO CHANTAL AKERMAN A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Kelly Marie Coyne, B.A. Washington, D.C. April 24, 2017 © 2017 Kelly Marie Coyne All rights reserved. ii “THE MAGIC MIRROR” UNCANNY SUICIDES, FROM SYLVIA PLATH TO CHANTAL AKERMAN Kelly Marie Coyne, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Dana Luciano, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Artists such as Chantal Akerman and Sylvia Plath, both of whom came of age in mid- twentieth century America, have a tendency to show concern with doubles in their work—Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman—and oftentimes situate their protagonists as doubles of themselves, carefully monitoring the distance they create between themselves and their double. This choice acts as a kind of self-constitution, by which I mean a self-fashioning that works through an imperfect mirroring of the text’s author presented as a double in a fictional work. Texts that employ self-constitution often show a concern with liminality, mirroring, consumption, animism, repressed trauma, suicide, and repetition. It is the goal of this thesis to examine these motifs in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and the early work of Chantal Akerman, all of which coalesce to create coherent—but destabilizing—texts that propose a new queer subject position, and locate the death drive—the desire to return to the mother’s womb—as their source. -

AGNÈS VARDA INTERVIEW This Interview Was Conducted by Rhonda Richford in Paris on January 31, 2019

PRESENTS Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Courtney Ott [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 646-230-6847 he final film from the late, beloved Agnès Varda is a characteristically Tplayful, profound, and personal summation of the director’s own brilliant career. At once impish and wise, Varda acts as our spirit guide on a free-associative tour through her six-decade artistic journey, shedding new light on her films, photography, and recent installation works while offering her one-of-a-kind reflections on everything from filmmaking to feminism to aging. Suffused with the people, places, and things she loved—Jacques Demy, cats, colors, beaches, heart-shaped potatoes—this wonderfully idiosyncratic work of imaginative autobiography is a warmly human, touchingly bittersweet parting gift from one of cinema’s most Agnès Varda filming Varda by Agnès luminous talents. France | 2019 | 120 minutes | Color | Stereo | 1.77:1 aspect ratio | Screening format: DCP DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT In 1994, with a retro at the Cinémathèque during that time, I mostly created art or not alone? In color or not in color? française, I published a book entitled installations, atypical triptychs, shacks of Creation is a job. Varda by Agnès. Twenty-five years later, cinema, and I kept making documentaries, The third word is sharing. You don’t the same title is given to my film made of such as The Beaches of Agnès. make films to watch them alone; you make moving images and words, with the same In the middle of the two parts, there films to show them. -

Dossier De Presse

Un film de Agnès Varda (An Emotion Picture) France / 1981 / Couleur / 63’ / 16 mm / Son Mono Restauré en 2011 par Ciné-Tamaris, la Fondation Groupama Gan pour le Cinéma et la Fondation Technicolor pour le Patrimoine du Cinéma Ecrit et réalisé par Agnès Varda Langue : français Couleur Durée : 63 mn Visa : 53.054 Distribution Production Sabine Mamou (Emily) Ciné-Tamaris Mathieu Demy (Martin) Scénario original : Agnès Varda Tom Taplin (Tom Cooper) Images : Nurith Aviv Delphine Seyrig (voix off) Musique : Georges Delerue Agnès Varda et Sabine Mamou Montage : Sabine Mamou (voix off des narratrices) Son : Jim Thornton Sortie : le 20 janvier 1982 en même temps qu’un autre film d’Agnès Varda, Mur Murs. Synopsis A Los Angeles, une Française, Emilie, séparée de l’homme qu’elle aime, cherche un logement pour elle et son fils de 8 ans, Martin. Elle en trouve un, y installe des meubles récupérés dans les déchets jetés à la rue. Son désarroi est plus exprimé par les autres qu’elle observe que par elle-même, vivant silencieusement un exil démultiplié. Elle tape à la machine face à l’océan. Quelques flashes de sa passion passée la troublent et elle consacre à son fils toute son affection. A propos de la restauration Une restauration menée fin 2010 et en 2011 par Ciné-Tamaris, la Fondation Groupama Gan pour le Cinéma et la Fondation Technicolor pour le Patrimoine du Cinéma. Cette restauration a été déclenchée par le tournage du premier long métrage de Mathieu Demy Americano, et la volonté de ce dernier d’insérer de nombreux extraits de Documenteur d’Agnès Varda dans lequel il jouait. -

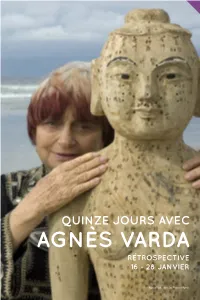

AGNÈS VARDA QUINZE JOURS AVEC RÉTROSPECTIVE 16 -28JANVIER Agnès Varda Dansles Plages D’Agnès 71

QUINZE JOURS AVEC AGNÈS VARDA AGNÈS AVEC JOURS QUINZE PROGRAMMATION QUINZE JOURS AVEC AGNÈS VARDA RÉTROSPECTIVE 16 - 28 JANVIER Agnès Varda dans Les Plages d’Agnès 71 Agnès Varda in Californialand UN GESTE LIBRE Elle a été la réalisatrice de la Nouvelle Vague, elle l’a même précédée. Elle débute comme photographe avant de réaliser son premier long métrage de fiction en 1954, La Pointe courte, remarqué pour l’audace de sa mise en scène. Cléo de 5 à 7, en 1962, témoigne d’une liberté de ton et de style en même temps qu’il parti- cipe d’une transformation de la pratique du cinéma menée tambour battant par une nouvelle génération. Depuis, elle n’a cessé de passer et repasser les fron- tières entre fiction et documentaire, essai et récit : Le Bonheur, Documenteur, Mur Murs, Sans toit ni loi, Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse, Les Plages d’Agnès… Cinéaste féministe, elle a toujours promis par ses films comme ses installations CINEMATHEQUE.FR un dépassement des genres, des comportements normés comme des limites Agnès Varda mode habituelles du cinéma lui-même. d’emploi : retrouvez une sélection subjective de 5 Ce qui frappe en premier lieu quand on prend en écharpe le corpus d’Agnès Varda, films dans la filmographie d’Agnès Varda, comme c’est son amplitude protéiforme. La native d’Ixelles (Belgique) a travaillé et joué autant de portes avec toutes les possibilités du cinéma : courts et longs métrages, fictions et docu- d’entrée dans l’œuvre. mentaires, noir et blanc et couleurs, argentique et numérique… Son travail a fini par déborder bien au-delà des limites du champ du cinéma, jusque dans les espaces À LA BIBLIOTHÈQUE de la Fondation Cartier ou sous le dôme vénérable du Panthéon à l’occasion de la cérémonie d’hommage aux Justes de France. -

Identity Slips: the Autobiographical Register in the Work of Chantal Akerman

Identity slips: the autobiographical register in the work of Chantal Akerman Article (Published Version) Lebow, Alisa (2016) Identity slips: the autobiographical register in the work of Chantal Akerman. Film Quarterly, 70 (1). pp. 54-60. ISSN 0015-1386 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61531/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk IDENTITY SLIPS: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL REGISTER IN THE WORK OF CHANTAL AKERMAN Alisa Lebow “Your mother was the thin thread that kept you in balance.” surrogates, for sets or actors, multiple screens, or even a —Esther Orner1 script.