SOME BRIEF COMMENTS on JAZZ in FILM by Ian Muldoon* ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dölerud Johansson Quintet

Dölerud Johansson Quintet Magnus Dölerud and Dan Johansson formed their quintet in 2016, bringing together some of Sweden’s most accomplished musicians. The members – Dan, Magnus, Torbjörn Gulz, Palle Danielsson and Fredrik Rundqvist – had previously crossed paths in other constellations, but this collaboration has resulted in something truly extra special. The quintet’s collective experience spans a long list of Swedish and International associations, from Keith Jarrett’s legendary European Quartet via the Fredrik Norén Band, which has spawned the careers of so many Swedish musicians over its 32- year history to the Norbotten Big Band, one of the most important jazz institutions in Sweden today, with collaborators like: Tim Hagans, Maria Schnieder, Joe Lovano, Bob Brookmeyer and Kurt Rosenwinkel. The quintet brings music to the stage that reflects that history, combining jazz tradition with the members’ own compositions. During 2017 and 2018, the band toured jazz clubs and festivals in Sweden and Finland, to warm receptions from audiences and reviewers alike. In May 2018, they recorded their first album, Echoes & Sounds, to be released this autumn. Dan Johansson Dan Johansson plays trumpet and flugelhorn in the Norbotten Big Band and is a well-established musician who has – in a career that extends over 30 years -- played with both the Swedish and International jazz elite. He became a member of the Norbotten Big Band while still a student and has played with the band since 1986. There he’s had the privilege to perform with figures like Randy Brecker, Peter Erskine, Joey Calderazzo, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Bob Berg. On top of his work with the big band, he’s played in a wide variety of smaller groups that have included: Håkan Broström. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

Page 13 Jak Można Zmienić Świat Na Lepszy?

News of Polonia Pasadena, California February 2009 Page 13 Music News - Komeda from 3 Jak można zmienić świat na lepszy? Antologia Wierszy Świat można zmienić na lepszy własnym przykładem. Polonijnych Lady], Ssaki [Mammals], Prawo i pięść [The Law and the Fist], Cul-de-sac, Ryszard Urbaniak Organizatorzy wieczoru poetycko- Bariera [Barrier], Dance of the Vampires, muzycznego Macieja Danka Le Départ, Rosemary’s Baby, and Riot. „Zatoka Poezji” oraz Zarząd Okręgu Throughout the 1960s Komeda travelled to numerous concerts and recording sessions in Sweden and Denmark, to European jazz festivals and, with his close friend, Roman Polański, to Hollywood. With so much success and recognition in Zapraszają polskich poetów Europe, it seemed that Komeda’s career in emigracyjnych do nadsyłania swojej the US film industry was assured. poezji, aby z nadesłanych wierszy, Unfortunately, after brain injuries jesienią 2009 roku utworzyć i wydać sustained in an accident in Los Angeles in drukiem Antologię Wierszy Polonijnych. December of 1968, Krzysztof Komeda Dochód ze sprzedaży przeznaczamy na lapsed into a coma and was transported to pomoc polskiemu harcerstwu Poland for further medical treatment. He w Kazachstanie. died on 23 April 1969 in Warsaw, Do dnia 31 maja 2009 roku, drogą following surgery. elektroniczną należy nadesłać: zdjęcie, Important initiatives have been krótką notę biograficzną i $ 20.00 poprzez undertaken by the Astigmatic Society in PayPal, na pokrycie kosztów wydania i Poland to commemorate the life and pomoc (nie)zapomnianym Polakom accomplishments of this extraordinary w Kazachstanie oraz jeden wiersz pianist and composer. In December 2008 w języku polskim, na adres: in Poznań, the Astigmatic Society held a [email protected] ceremony for the unveiling of a Jeszcze niespełna rok temu zapadający się powoli pod ziemię budynek ośrodka East Czek na wyżej wymienioną kwotę, commemorative plaque on the building Bay Polish-American Association w kalifornijskim Martinez, odstraszał. -

Retrospektive Roman Polanski the PIANIST Roman Polanski

Retrospektive Roman Polanski THE PIANIST Roman Polanski 31 Roman Polanski bei den Dreharbeiten zu Kino der Heimsuchung kennen. Und doch wird der Zuschauer augenblicklich Als die Cinémathèque française im Oktober letzten in den Bann des Films gezogen, in dessen Verlauf die Jahres eine große Ausstellung über die Geschichte der mulmige Enge nachbarschaftlichen Zusammenwoh- Filmtechnik eröffnete, fungierte er als Pate. Eine klü- nens nach und nach in einen Albtraum umschlägt. gere Wahl hätte die Pariser Kinemathek nicht treffen können, denn Roman Polanski hat immer wieder be- Ein Treibhauseffekt tont, wie unverzichtbar für ihn das Handwerk ist, das er Als LE LOCATAIRE 1976 herauskam, fügte er sich in an der Filmhochschule erlernt hat. Darin unterscheide einen Zyklus der klaustrophobisch-pathologischen Er- er sich, bemerkte der Regisseur mit maliziösem Stolz, zählungen, den der Regisseur ein Jahrzehnt zuvor mit doch ganz erheblich von seinen Freunden von der Nou- REPULSION (EKEL) und ROSEMARY'S BABY begonnen velle Vague, die als Filmkritiker angefangen hatten. hatte. Ihr erzählerischer Radius beschränkt sich weitge- Zur Eröffnung der Ausstellung präsentierte er LE hend auf einen Schauplatz. Der filmische Raum ist für LOCATAIRE (DER MIETER), der seinen virtuosen Um- diesen Regisseur eine Sphäre der Heimsuchung, an- gang mit der Technik spektakulär unter Beweis stellt. fangs auch der Halluzinationen und surrealen Verwand- 1976 war er der erste Filmemacher, der den Kamera- lungen. Sich auf einen Handlungsort zu konzentrieren, kran Louma einsetzte. Die Exposition des Films ist eine ist für ihn keine Begrenzung, sondern eine Herausfor- überaus akrobatische Kameraoperation, eine Kombi- derung an seine visuelle und dramaturgische Vorstel- nation aus Fahrten und Schwenks, der die Fassaden lungskraft. -

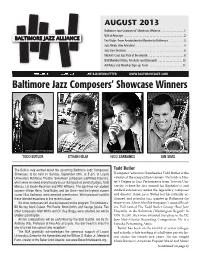

Baltimore Jazz Composers' Showcase Winners

AUGUST 2013 Baltimore Jazz Composers’ Showcase Winners . 1 BJA at Artscape . 2 Fay Victor: From Amsterdam to Mumbai to Baltimore . 3 BALTIMORE JAZZ ALLIANCE Jazz Meets Film Revisited . 4 Jazz Jam Sessions . 8 WEAA’s Cool Jazz Pick of the Month . 8 BJA Member Notes, Products and Discounts . 10 Ad Rates and Member Sign-up Form . 11 VOLUME X ISSUE VIII THE BJA NEWSLETTER WWW.BALTIMOREJAZZ.COM Baltimore Jazz Composers’ Showcase Winners PHOTO COURTESY OF TODD BUTLER PHOTO COURTESY OF ETHAN HELM PHOTO COURTESY OF NICO SARBANES PHOTO COURTESY OF IIAN SIIMS TODD BUTLER ETHAN HELM NICO SARBANES IAN SIMS The BJA is very excited about the upcoming Baltimore Jazz Composers’ Todd Butler Showcase, to be held on Sunday, September 29th, at 5 pm, at Loyola Trumpeter/educator/bandleader Todd Butler is the University’s McManus Theatre. Seventeen composers submitted materials, veteran of the competition winners. He holds a Mas - which were reviewed anonymously by our distinguished panel of judges, Todd ter’s Degree in Jazz Performance from Towson Uni - Marcus, Liz Sesler-Beckman and Whit Williams. The top three non-student versity (where he also earned his Bachelor’s) and scorers—Ethan Helm, Todd Butler, and Ian Sims—and the highest student studied extensively under the legendary composer scorer, Nico Sarbanes, were awarded commissions. We’re pleased to profile and director Hank Levy. Butler led his critically ac - these talented musicians in this month’s issue. claimed and popular jazz quintet in Baltimore for Six other composers will also be featured on the program: Tim Andrulonis, many years. Music Monthly magazine’s annual Read - Bill Murray, Mark Osteen, Phil Ravita, Brian Smith, and George Spicka. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

'Helikon' Was Also a Favourite of Zbyszek Seifert's. Both His Quartet

man of the light. THE LIFE AND WORK OF ZBIGNIEW SEIFERT The ‘Helikon’ was also a favourite of Zbyszek Seifert’s. Both his quartet and (later) Stańko’s quintet held their rehearsals there, and that’s where he played his first jazz concerts. It was in this club that he met jazz musicians and fans. As its musicians became more and more popular, the Jazz-Club found it could not seat all the audience and so concerts began to be held in other places. Nonetheless, the first steps on the ensemble’s career path were inextricably linked with that magical place. Jazz-Club “Helikon”. From left: barmaid, NN, Jan Jarczyk, Zbigniew Seifert, Jan Gonciarczyk, Adam Matyszkowicz. Archive of Małgorzata Seifert Jazz-Club “Helikon” membership card. Archive of Małgorzata Seifert 36 The music studies and Jazz Ensembles The Career of the Zbigniew Seifert Quartet The Quartet’s official debut took place in November, 1965, during the th14 Cracow Jazz Festival, the so-called Cracow All Souls Jazz Festival at Krzysztofory, where the jam sessions were held. Andrzej Jaroszewski enthusiastically hailed their performance as foreshadowing the coming of a new generation of jazz musicians, the debut of a modern jazz band. In a brochure entitled “Cracow Jazz Festival – 14th Edition”, Krzysztof Sadowski wrote: On Friday evening the second debutant was Zbigniew Seifert, an alto sax player influenced by John Coltrane and Zbigniew Namysłowski. From the latter, he took the pure intonation and confident presentation of frequently complicated melodic phrases. Especially in the theme of McCoy Tyner’s “Three Flowers” the whole ensemble gave us a sample of solid modern jazz. -

Jazz Et Cinéma

1 2 Présentation du conférencier Daniel Brothier est musicien, compositeur, et il joue des saxophones alto et baryton. Ses créations musicales sont axées sur plusieurs pôles : des mixes et des remixes de musique électronique, des compositions pour le jazz et les musiques nouvelles, des créations de musiques de théâtre, de cinéma et de danse, des transcriptions de musique classique. D’une part il compose de la musique sur le papier, et d’autre part, construit, diffuse et produit ses musiques à l’aide d'outils d'informatique musicale. Il est l’initiateur des duos et trios électro-funk Total RTT et Bloom. Conférencier sur les musiques électroniques et le jazz, il a donné plus de 350 conférences- concerts depuis 2007. Il est venu à la médiathèque de Vincennes en novembre 2011 pour présenter sa conférence Miles Davis, une histoire du jazz du be bop au hip hop. Daniel possède un diplôme d’état de professeur de musique de jazz. http://www.brotski.fr/ 3 Jazz et cinéma Jazz et cinéma… Pour le cinéphile ou le jazzfan d'aujourd'hui, l'association relève de l'évidence. D'Ascenseur pour l'échafaud à Whiplash, chacun a en tête au moins une scène où le jazz joue un rôle majeur. Et que celui qui n'a jamais fredonné le thème de La Panthère rose lève le doigt ! Pourtant, depuis leur apparition à l'aube du XXème siècle, les deux arts n'ont cessé d'entretenir des relations ambigües, entre fascination réciproque et incompréhension. A y regarder de plus près, l'alchimie n'a pas toujours fonctionné. -

Leszek Możdżer

Leszek Mo żdżer Komeda ACT 9516-2 German Release Date: June 24, 2011 For many years, jazz and classical music trod a common path of mutual enrichment, with Bartók to Stokowski and Horowitz on the one hand, and Art Tatum, George Gershwin and even Benny Goodman on the other. This relationship was fractured by the break in culture caused by the Second World War, and despite several attempts – for example, the “Third Stream” movement at the end of the 1950s – it took a long time before the exchange between the two most important trends in art music became matter of course again. If jazz is today once again regarded as the “second classical music”, it is because of artists such as the Polish pianist Leszek Mo żdżer. The classically trained pianist was born in 1971. While he didn’t discover jazz himself until he was 18 years old, he quickly made a name for himself and is today celebrated like a pop star in Poland, where he has played with the country’s most important jazz musicians including Tomasz Stanko and Michal Urbaniak. Since 1994 until the present day he has been voted, almost without exception, the best pianist of the country by the Polish Jazzforum magazine. Mo żdżer has also made a name for himself internationally, particularly alongside Swedish bassist Lars Danielsson whose music is similarly dedicated to melody. He described Mo żdżer as, “the ideal pianist for me” and recorded both his last albums – “Pasodoble” (2007) and “Tarantella” (2009) – with him. American jazz icons such as Pat Metheny, Lester Bowie and Archie Shepp are also vocal in their appreciation of his work. -

John Williams John Williams

v8n01 covers 1/28/03 2:18 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 1 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Trek’s Over pg. 36 &The THE Best WORST Our annual round-up of the scores, CDs and composers we loved InOWN Their WORDS Shore, Bernstein, Howard and others recap 2002 DVDs & CDs The latestlatest hits hits ofof thethe new new year year AND John Williams The composer of the year in an exclusive interview 01> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v8n01 issue 1/28/03 12:36 PM Page 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 14 The Best (& the Worst) of 2002 Listening on the One of the best years for film music in recent Bell Curve. memory? Or perhaps the worst? We’ll be the judges of that. FSM’s faithful offer their thoughts 4 News on who scored—and who didn’t—in 2002. Golden Globe winners. 5 Record Label 14 2002: Baruch Atah Adonei... Round-up By Jon and Al Kaplan What’s on the way. 6 Now Playing 18 Bullseye! Movies and CDs in By Douglass Fake Abagnale & Bond both get away clean! release. 12 7 Upcoming Film 21 Not Too Far From Heaven Assignments By Jeff Bond Who’s writing what for whom. 22 Six Things I’ve Learned 8 Concerts About Film Scores Film music performed By Jason Comerford around the globe. 24 These Are a Few of My 9 Mail Bag Favorite Scores Ballistic: Ennio vs. Rolfe. By Doug Adams 30 Score 15 In Their Own Words The latest CD reviews, Peppered throughout The Best (& the Worst) of including: The Hours, 2002, composers Shore, Elfman, Zimmer, Howard, Film scores in 2002—what a ride! Catch Me If You Can, Bernstein, Newman, Kaczmarek, Kent and 21 Narc, Ivanhoe and more.