Technology Ties: Getting Real After Microsoft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Can Apple TV™ Teach Us About Digital Signage?

What can Apple TV™ teach us about Digital Signage? Mark Hemphill | @ScreenScape July 2016 Executive Summary As a savvy communicator, you could be increasing revenue by building dynamic media channels into every one of your business locations via digital signage, yet something is holding you back. The cost and complexity associated with such technology is still too high for the average business owner to tackle. Or is it? Some of the traditional vendors in the digital signage industry make the task of connecting and controlling a few screens out to be a momentous challenge, a task for high paid experts. On the other hand, a new class of technologies has arrived in the home entertainment world that strips the exercise down to basics. And it’s surging in popularity. Apple TV™, and other similar streaming Internet devices, have managed to successfully eliminate the need for complicated hardware and complex installation processes to allow average non-technical homeowners to bring the Internet to their television screens. This trend in consumer entertainment offers insights we can adapt to the commercial world, lessons for digital signage vendors and their customers, which lead towards to simpler, more cost-effective, more user-friendly, and more scalable solutions. This article explores some of the following lessons in detail: • Simple appliances outperform PCs and Macs as digital media players • Sourcing and mounting a TV is not the critical challenge • In order to scale, digital signage networks must be designed for average non-technical users to operate • Creating an epic viewing experience isn’t as important as enabling a large and diverse network • Simplicity and cost-effectiveness go hand in hand By making it easier to connect and control screens, tomorrow’s digital signage solutions will help more businesses to reap the benefits of place-based media. -

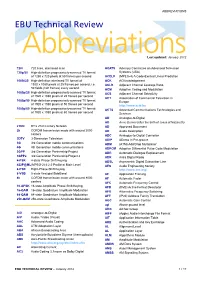

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Review: a Digital Video Player to Support Music Practice and Learning Emond, Bruno; Vinson, Norman; Singer, Janice; Barfurth, M

NRC Publications Archive Archives des publications du CNRC ReView: a digital video player to support music practice and learning Emond, Bruno; Vinson, Norman; Singer, Janice; Barfurth, M. A.; Brooks, Martin This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur. Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur: Journal of Technology in Music Learning, 4, 1, 2007 NRC Publications Record / Notice d'Archives des publications de CNRC: https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=2573dfda-4fa0-4a7f-b8e0-4014b537e486 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=2573dfda-4fa0-4a7f-b8e0-4014b537e486 Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB. Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at [email protected]. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information. Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. -

Cutting the Cable Cord

3/11/2021 The views, opinions, and information expressed during this • March 11, 6:30-7:30 PM webinar are those of the presenter and are not the views or opinions of the Newton Public Library. The Newton Public Library • FREE! NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED makes no representation or warranty with respect to the webinar or any information or materials presented therein. Users of webinar materials should not rely upon or construe the Thinking of cutting the cord? What are your options? ChromeCast information or resource materials contained in this webinar as Why and why not do it, Apple TV, Roku alternatives and more sources of entertainment. Sling, Hulu, Netflix legal or other professional advice and should not act or fail to act To log in live from home go to: based on the information in these materials without seeking the services of a competent legal or other specifically specialized https://kslib.zoom.us/j/561178181 professional. Watch the recorded presentation anytime after the 15th or Recorded https://kslib.info/1180/Digital-Literacy---Tech-Talks Presenter: Nathan, IT Supervisor, at the Newton Public Library 1. Protect your computer • A computer should always have the most recent updates installed for spam filters, anti-virus and anti-spyware software and http://www.districtdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/triple_play_web.png a secure firewall. http://cdn.greenprophet.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/frying-pan-kolbotek-neoflam-560x475.jpg What is “Cutting the Cord” Cable TV Cord Cutting (verb): The act of canceling your cable or Cable is the immediate answer satellite subscription in favor of a more affordable and obvious choice with the most television viewing option. -

Software Installation

Software Installation Please note students should not uninstall any software from this list Software Rationale Windows 8.1 Professional/Windows 10 (64 Bit) Nb Microsoft Edge Browser is not compatible with some websites and they will require opening in IE V11 Acrobat Reader To open pdf Documents https://get.adobe.com/reader/ Adobe Digital Editions Software program used to read ebooks http://www.adobe.com/au/solutions/ebook/digital- editions/download.html Pearson Bookshelf EBook reader for school textbooks https://www.pearsonplaces.com.au/help/ctl/article/mi d/6911.aspx?articleId=34 Java Runtime Environment Enabled execution of Java applications https://java.com/en/download/ Adobe Shockwave Player Allows execution of Director applications in web https://get.adobe.com/shockwave/ Browsers (Not required for Windows 10) Adobe Flash Player Used to view animations and movies in web browsers https://helpx.adobe.com/flash-player.html Microsoft Office 2016 Pro Plus including Word, Excel, Nb: This is available at no cost via the school’s Office365 Powerpoint, Onenote, Publisher & Onenote plugin Subscription. Learning Tools for Onenote Word: Word processor Excel: Spreadsheet application https://www.onenote.com/learningtools Publisher: Desktop publishing application PowerPoint: Presentation application Powepoint Plugin OfficeMix OneNote: Electronic note making and multimedia https://mix.office.com/en-us/Home container. Learning tools allows support for English Office Mix interactivity+screen video for powerpoint Outlook – email and personal information -

DIGITAL Media Players Have MEDIA Evolved to Provide PLAYERS a Wide Range of Applications and Uses

2011-2012 Texas 4-H Study Guide - Additional Resources DigitalDIGITAL media players have MEDIA evolved to provide PLAYERS a wide range of applications and uses. They come in a range of shapes and sizes, use different types of memory, and support a variety of file formats. In addition, digital media players interface differently with computers as well as the user. Consideration of these variables is the key in selecting the best digital media player. In this case, one size does not fit all. This guide is intended to provide you, the consumer, with information that will assist you in making the best choice. Key Terms • Digital Media Player – a portable consumer electronic device that is capable of storing and playing digital media. The data is typically stored on a hard drive, microdrive, or flash memory. • Data – information that may take the form of audio, music, images, video, photos, and other types of computer files that are stored electronically in order to be recalled by a digital media player or computer • Flash Memory – a memory chip that stores data and is solid-state (no moving parts) which makes it much less likely to fail. It is generally very small (postage stamp) making it lightweight and requires very little power. • Hard Drive – a type of data storage consisting of a collection of spinning platters and a roving head that reads data that is magnetically imprinted on the platters. They hold large amounts of data useful in storing large quantities of music, video, audio, photos, files, and other data. • Audio Format – the file format in which music or audio is available for use on the digital media player. -

X2o Media Player-Dx

X2O MEDIA PLAYER-DX The X2O Media Player-DX is a dual 4K output digital media player that delivers enterprise performance and seamless playback of 4K content. The media player works seamlessly with the X2O Platform, matching powerful, stable performance with turnkey simplicity. An optimized architecture ensures high quality performance throughout its entire lifetime. System hardening minimizes vulnerabilities and delivers robust system security. The media player’s fanless design keeps it protected from dust and debris, ideal for any digital signage solution in any environment. SMALL FOOTPRINT, OPTIMIZED ARCHITECTURE COMMERCIAL-GRADE BIG PERFORMANCE FOR DIGITAL SIGNAGE RELIABILITY Learn more about X2O Media Players at www.x2omedia.com TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION Description Specification CPU AMD V1202B Dual-core 2.3 GHz/3.2 GHz GPU Integrated AMD Radeon Vega 3 Operating System Windows 10 IoT Enterprise 2019 LTSC Memory 8 GB DDR4 SO-DIMM RAM (dual-channel) Storage 64 GB M.2 SATA SSD Power DC 12 V with screw lock HDMI Two HDMI 2.0 ports with screw lock Auxilary Audio One 3.5 mm Dual Gigabit Ethernet port, wireless IEEE 802.11 a/b/g/n/ac Wi-Fi, Network Bluetooth 4.2 Antenna Two 2.4 GHz / 5 GHz dual-band antenna USB Two USB 3.1 Type A ports, One USB 3.0 Type A port Serial One DB9 Male Switches: POWER, CLEAR CMOS, RESET, EDID Emulator control buttons Other I/O LEDs: Power, SSD, WiFi Power button extension RJ11 Dimensions (WxDxH) 300 x 186 x 32 mm / 11.8 x 7.3 x 1.3 in Net Weight 2145 g / 4.7 lb Enclosure Anodized aluminum case, fanless Storage Temperature -55° - 75° C / -67° - 167° F Working Temperature -10° - 45° C / 14° - 113° F Storage/Working Humidity 5 - 95% Non-condensing Option 1 Cloud-based CMS Option 2 On-premise CMS DX Player Digital Signage Screen Learn more about X2O Media Players at www.x2omedia.com. -

Accessing Voice Messages Via Email

Accessing voice messages via email Download a digital media player Play a message using Windows Media Player (if you do not already have one): (when WMP is your default media player): 1. Windows Media Player: 1. Open the email message. http://www.microsoft.com/windows/windowsmedia/player/ (NOTE: There is no previewer available for Windows Media 2. Apple’s iTunes: Player. Therefore, you cannot play the voice message by http://www.apple.com/itunes/overview/ clicking on the media player from the Preview pane.) 3. RealNetworks RealPlayer: 2. Double‐click on the .wav file attachment. The Windows http://www.real.com/realplayer Media Player application will launch automatically. What will happen if I open a voicemail message before I have downloaded a media player? 1. When you try to open the voice mail in Outlook, the following message will appear on your screen before the message is opened…. 2. When you click on the OK button, the message will open in a separate window….. 3. Follow the standard Windows Media Player procedures to play, rewind, save, or delete the voice mail message(s). To play a voice mail message from iTunes (when iTunes is your default media player): 1. Right‐click on the voice mail message in your email 3. If you double‐click on the attached .wav file, the following message Inbox. will appear…. 2. From the drop‐down menu, move your cursor to the View Attachments option and then click on VoiceMessage.wav from the sub‐list. 4. Make sure that the Express Settings donut is selected, then click on 3. -

HULU and the FUTURE of TELEVISION: a CASE STUDY An

HULU AND THE FUTURE OF TELEVISION: A CASE STUDY An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Matthew Rodgers Thesis Advisor Michael Hanley Associate Professor of Journalism Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2011 Expected Date of Graduation May 2011 Abstract Understanding current media trends and adapting to ever-changing consumer desires is essential to success in advertising. Hulu is one of several new Internet-based services that deliver television content to consumers without using the traditional broadcast or cable channels used in the recent past. This document compiles information concerning this new service and presents it as a case study for the evolving television market, especially as it concerns advertisers. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their patience, understanding, guidance and encouragement throughout the duration of this project: Michael Hanley Kevin and Karen Rodgers Katie Mathieu Nathan Holmes and Noah Judd microPR: Joey Lynn Foster, Kenzie Grob, Kati Ingerson, Ben Luttrull and Adam Merkel 3 Table of Contents I. Abstract ..............................................................,........................... " ...... 2 II. Acknowledgements ... '" ........... .. .. ........... ... ................. .... ....... .................... 3 III. Table of Contents ............................. ................ .... ...................................... 4 IV. Statement of Problem ...... ...... ............ .. ...................................................... 5 V. Methodology ............ '" -

A Transcoding Server for the Home Domain

A Transcoding Server for the Home Domain François Caron and Stéphane Coulombe Tao Wu Department of Software and IT Engineering Nokia Research Center École de Technologie Supérieure Cambridge, MA 02142, USA Montréal, Canada [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—This paper discusses the implementation of a video When this project was started, only the Design Guidelines transcoding service for the Home Domain. The Home Domain is of version 1 had been released. The mandatory media formats composed of personal computers, consumer electronics and were LPCM for audio, JPEG (resolution of 640x480 noted as mobile devices that communicate with each other via an IP small) for images and MPEG-2 for video. These formats are network. However, due to the diversity of the capabilities of these widely supported by consumer electronic devices such as devices (formats supported, memory, processing power, etc), DVD, STB, etc. However, LPCM and MPEG-2 are not interoperability is a challenge. For instance, set-top boxes and supported by mobile devices and the Design Guidelines did not DVD players support the MPEG-2 video format while mobile contain any transcoding entity to enable multimedia content phones only support H.263 and/or MPEG-4. Adding a video interoperability between devices. Under such situations, it was transcoding service, acting as an intermediate between a digital problematic to include mobile devices in the Home Domain. media server and various digital media players, would allow transparent sharing of the media content within the network. For instance, a wireless device (either a mobile phone or a This study has two main objectives. -

Model Smpv-4Gbeb Digital Media Player

MODEL SMPV-4GBEB DIGITAL MEDIA PLAYER PLEASE READ THIS USER MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE OPERATING THIS UNIT AND RETAIN THIS BOOKLET FOR FUTURE DEAR JENSEN CUSTOMER Selecting fine audio equipment such as the unit you've just purchased is only the start of your musical enjoyment. Now it's time to consider how you can maximize the fun and excitement your equipment offers. This manufacturer and the Electronic Industries Association's Consumer Electronics Group want you to get the most out of your equipment by playing it at a safe level. One that lets the sound come through loud and clear without annoying blaring or distortion and, most importantly, without affecting your sensitive hearing. Sound can be deceiving. Over time your hearing "comfort level" adapts to higher volumes of sound. So what sounds "normal" can actually be loud and harmful to your hearing. Guard against this by setting your equipment at a safe level BEFORE your hearing adapts. To establish a safe level: - Start your volume control at a low setting. - Slowly increase the sound until you can hear it comfortably and clearly and without distortion. Once you have established a comfortable sound level: Set the dial and leave it there. Taking a minute to do this now will help to prevent hearing damage or loss in the future. After all, we want you listening for a lifetime. We Want You Listening For a Lifetime Used wisely, your new sound equipment will provide a lifetime of fun and enjoyment. Since hearing damage from loud noise is often undetectable until it is too late, this manufacturer and the Electronic Industries Association's Consumer Electronics Group recommend you avoid prolonged exposure to excessive noise. -

VP71 EXCLUSIVE Multimedia Player

VP71 EXCLUSIVE Multimedia Player At A Glance Videotel Digital’s EXCLUSIVE VP71 is an industrial grade RS232 digital media player designed for any video content. The VP71 automatically loops content loaded on SD Card or USB drive (both included). Solid-state technology VP71 provides crystal clear and sharp picture quality without degradation regardless of the number of playbacks. The VP71 outputs video resolutions from 480p to 1080p. Connects to any NTSC, PAL, HDMI or VGA monitor, multimedia POP displays. Highlighted Features Specifications • Supports multiple forms of playback: System Type: Digital Audio/Video/Picture playback Photo/Video/Audio Video Formats: .avi .vob .dat .iso .mkv .mov .mp4 .mpg .mpeg .ts .mets • Video out: VGA, HDMI, and Composite Video .wmv .rm .rmvb .flv • Audio out: Stereo L/R (line level) Video Codec: mpeg1, mpeg2, mpeg4, divx, h.263, h.264, wmv9, vc-1, rmvb • Supports SD Card & USB Drive Audio Formats: .mp2 .mp3 .wma .ogg .flac .wav .aac .mid • Compact size: easily integrated into any size and style display Audio Codec: aac, ac3, atra, ape, dts, flac, ogg, mp3, wma, wma pro • Auto-play when powered ON Photo Formats: JPEG, TIFF, BMP • Outputs NTSC and PAL Dimension: 5 .5” (L) x 3.5”(W) x 1.125”(H) • 2 Year warranty Power Supply: 100VAC - 240VAC input / 5.5VDC (1.5A) • Simple to navigate menu using remote control USB Jack: USB 2.0 • RS232 communication ready SD Reader: SD 32 GB / MMC 32 GB • Trigger videos from dry contact interface harness Video Output: NTSC/PAL/VGA/HDMI Audio Output: Stereo L/R (line level) I/O