Psychotropics and the Microbiome: a Chamber of Secrets…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review on Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries

mac har olo P gy : & O y r p t e s i n Biochemistry & Pharmacology: Open A m c e c h e c Ravalli, et al. Biochem Pharmacol 2015, 4:2 s o i s B Access DOI: 10.4172/2167-0501.1000r001 ISSN: 2167-0501 Review Open Access A Review on Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries Ravalli R1*, NavaJyothi CH2, Sushma B3 and Amala Reddy J4 1Deparment of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Andhra University, Vishakapatnam, India 2University College of Technology, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India 3Deparment of Medicinal Chemistry, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER) Hyderabad, India 4Deparment of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India *Corresponding author: Ravalli R, Deparment of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Andhra University, Vishakapatnam, India, Tel: + 0437-869-033; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: April 13, 2015; Accepted date: April 14, 2015; Published date: April 21, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Ravalli Remella. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestri cted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Availability of Antimicrobial Drugs isolates were proof against Principen, Co-trimoxazole, and bactericide, and 14-40% were given with Mecillinam [6]. This was associate degree Although foremost potent and recently developed antimicrobial outsized increase over the half resistant isolates notable in 1991, before medicine are offered throughout the globe, in developing countries the drug was wide on the market. Throughout infectious disease their use is confined to people who are flush enough to afford them. In epidemics the organism has the flexibleness to develop increasing tertiary referral hospitals like the Kenyatta National Hospital in resistance, typically by acquisition of plasmids. -

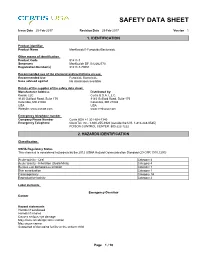

Mankocide® Fungicide/Bactericide

SAFETY DATA SHEET Issue Date 25-Feb-2017 Revision Date 25-Feb-2017 Version 1 1. IDENTIFICATION Product identifier Product Name ManKocide® Fungicide/Bactericide Other means of identification Product Code 91411-7 Synonyms ManKocide DF, B12262770 Registration Number(s) 91411-7-70051 Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use Recommended Use Fungicide Bactericide Uses advised against No information available Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Manufacturer Address Distributed by: Kocide LLC Certis U.S.A. L.L.C. 9145 Guilford Road, Suite 175 9145 Guilford Road, Suite 175 Columbia, MD 21046 Columbia, MD 21046 USA USA Website: www.kocide.com www.certisusa.com Emergency telephone number Company Phone Number Certis USA +1 301-604-7340 Emergency Telephone ChemTel, Inc.: 1-800-255-3924 (outside the U.S. 1-813-248-0585) POISON CONTROL CENTER: 800-222-1222 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Classification OSHA Regulatory Status This chemical is considered hazardous by the 2012 OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200) Acute toxicity - Oral Category 4 Acute toxicity - Inhalation (Dusts/Mists) Category 4 Serious eye damage/eye irritation Category 1 Skin sensitization Category 1 Carcinogenicity Category 1A Reproductive toxicity Category 2 Label elements Emergency Overview Danger Hazard statements Harmful if swallowed Harmful if inhaled Causes serious eye damage May cause an allergic skin reaction May cause cancer Suspected of damaging fertility or the unborn child _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Pharmacomicrobiomics: a Novel Route Towards Personalized Medicine?

Protein Cell 2018, 9(5):432–445 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-018-0547-2 Protein & Cell REVIEW Pharmacomicrobiomics: a novel route towards personalized medicine? Marwah Doestzada1,2, Arnau Vich Vila1,3, Alexandra Zhernakova1, Debby P. Y. Koonen2, Rinse K. Weersma3, Daan J. Touw4, Folkert Kuipers2,5, Cisca Wijmenga1,6, Jingyuan Fu1,2& 1 Departments of Genetics, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 2 Departments of Paediatrics, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Departments of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 4 Departments of Clinical Pharmacy & Pharmacology, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands Cell 5 Departments of Laboratory Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, & The Netherlands 6 K.G. Jebsen Coeliac Disease Research Centre, Department of Immunology, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1072, Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway & Correspondence: [email protected] (J. Fu) Received March 5, 2018 Accepted April 16, 2018 Protein ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Inter-individual heterogeneity in drug response is a Individual responses to a specific drug vary greatly in terms serious problem that affects the patient’s wellbeing and of both efficacy and toxicity. It has been reported that poses enormous clinical and financial burdens on a response rates to common drugs for the treatment of a wide societal level. Pharmacogenomics has been at the variety of diseases fall typically in the range of 50%–75%, forefront of research into the impact of individual indicating that up to half of patients are seeing no benefit genetic background on drug response variability or drug (Spear et al., 2001). -

The Antimicrobial Agent Fusidic Acid Inhibits Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide–Mediated Hepatic Clearance and May Potentiate Statin-Induced Myopathy

1521-009X/44/5/692–699$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/dmd.115.067447 DRUG METABOLISM AND DISPOSITION Drug Metab Dispos 44:692–699, May 2016 Copyright ª 2016 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics The Antimicrobial Agent Fusidic Acid Inhibits Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide–Mediated Hepatic Clearance and May Potentiate Statin-Induced Myopathy Heather Eng, Renato J. Scialis, Charles J. Rotter, Jian Lin, Sarah Lazzaro, Manthena V. Varma, Li Di, Bo Feng, Michael West, and Amit S. Kalgutkar Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Metabolism Department–New Chemical Entities, Pfizer Inc., Groton, Connecticut (H.E., R.J.S., C.J.R., J.L., S.L., M.V.V., L.D., B.F., M.W.); and Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Metabolism Department–New Chemical Entities, Pfizer Inc., Cambridge MA (A.S.K.) Received September 28, 2015; accepted February 12, 2016 Downloaded from ABSTRACT Chronic treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with an IC50 value of 157 6 1.0 mM and was devoid of breast strains with the bacteriostatic agent fusidic acid (FA) is frequently cancer resistance protein inhibition (IC50 > 500 mM).Incontrast, associated with myopathy including rhabdomyolysis upon coad- FA showed potent inhibition of OATP1B1- and OATP1B3-specific ministration with statins. Because adverse effects with statins are rosuvastatin transport with IC50 values of 1.59 mM and 2.47 mM, usually the result of drug–drug interactions, we evaluated the respectively. Furthermore, coadministration of oral rosuvastatin dmd.aspetjournals.org -

Pharmacogenetic Testing: a Tool for Personalized Drug Therapy Optimization

pharmaceutics Review Pharmacogenetic Testing: A Tool for Personalized Drug Therapy Optimization Kristina A. Malsagova 1,* , Tatyana V. Butkova 1 , Arthur T. Kopylov 1 , Alexander A. Izotov 1, Natalia V. Potoldykova 2, Dmitry V. Enikeev 2, Vagarshak Grigoryan 2, Alexander Tarasov 3, Alexander A. Stepanov 1 and Anna L. Kaysheva 1 1 Biobanking Group, Branch of Institute of Biomedical Chemistry “Scientific and Education Center”, 109028 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (T.V.B.); [email protected] (A.T.K.); [email protected] (A.A.I.); [email protected] (A.A.S.); [email protected] (A.L.K.) 2 Institute of Urology and Reproductive Health, Sechenov University, 119992 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (N.V.P.); [email protected] (D.V.E.); [email protected] (V.G.) 3 Institute of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Sechenov University, 119992 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-499-764-9878 Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 17 December 2020; Published: 19 December 2020 Abstract: Pharmacogenomics is a study of how the genome background is associated with drug resistance and how therapy strategy can be modified for a certain person to achieve benefit. The pharmacogenomics (PGx) testing becomes of great opportunity for physicians to make the proper decision regarding each non-trivial patient that does not respond to therapy. Although pharmacogenomics has become of growing interest to the healthcare market during the past five to ten years the exact mechanisms linking the genetic polymorphisms and observable responses to drug therapy are not always clear. Therefore, the success of PGx testing depends on the physician’s ability to understand the obtained results in a standardized way for each particular patient. -

Antibiotic Resistance in Plant-Pathogenic Bacteria

PY56CH08-Sundin ARI 23 May 2018 12:16 Annual Review of Phytopathology Antibiotic Resistance in Plant-Pathogenic Bacteria George W. Sundin1 and Nian Wang2 1Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; email: [email protected] 2Citrus Research and Education Center, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Lake Alfred, Florida 33850, USA Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018. 56:8.1–8.20 Keywords The Annual Review of Phytopathology is online at kasugamycin, oxytetracycline, streptomycin, resistome phyto.annualreviews.org https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417- Abstract 045946 Antibiotics have been used for the management of relatively few bacterial Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. plant diseases and are largely restricted to high-value fruit crops because of Access provided by INSEAD on 06/01/18. For personal use only. All rights reserved the expense involved. Antibiotic resistance in plant-pathogenic bacteria has Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018.56. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org become a problem in pathosystems where these antibiotics have been used for many years. Where the genetic basis for resistance has been examined, antibiotic resistance in plant pathogens has most often evolved through the acquisition of a resistance determinant via horizontal gene transfer. For ex- ample, the strAB streptomycin-resistance genes occur in Erwinia amylovora, Pseudomonas syringae,andXanthomonas campestris, and these genes have pre- sumably been acquired from nonpathogenic epiphytic bacteria colocated on plant hosts under antibiotic selection. We currently lack knowledge of the effect of the microbiome of commensal organisms on the potential of plant pathogens to evolve antibiotic resistance. -

Live Biotherapeutic Products, a Road Map for Safety Assessment

Live Biotherapeutic Products, A Road Map for Safety Assessment Alice Rouanet, Selin Bolca, Audrey Bru, Ingmar Claes, Helene Cvejic, Haymen Girgis, Ashton Harper, Sidonie Lavergne, Sophie Mathys, Marco Pane, et al. To cite this version: Alice Rouanet, Selin Bolca, Audrey Bru, Ingmar Claes, Helene Cvejic, et al.. Live Biotherapeutic Products, A Road Map for Safety Assessment. Frontiers in Medicine, Frontiers media, 2020, 7, 10.3389/fmed.2020.00237. hal-02900344 HAL Id: hal-02900344 https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02900344 Submitted on 8 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS published: 19 June 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00237 Live Biotherapeutic Products, A Road Map for Safety Assessment Alice Rouanet 1, Selin Bolca 2†, Audrey Bru 3†, Ingmar Claes 4†, Helene Cvejic 5,6†, Haymen Girgis 7†, Ashton Harper 8†, Sidonie N. Lavergne 9†, Sophie Mathys 10†, Marco Pane 11†, Bruno Pot 12,13†, Colette Shortt 14†, Wynand Alkema 15, Constance Bezulowsky 16, Stephanie Blanquet-Diot 17, Christophe Chassard 18, Sandrine P. Claus 19, Benjamin Hadida 20, Charlotte Hemmingsen 21, Cyrille Jeune 7, Björn Lindman 22, Garikai Midzi 8, Luca Mogna 11, Charlotta Movitz 22, Nail Nasir 23, 24 25 25 26 Edited by: Manfred Oberreither , Jos F. -

Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance Of

01 Pan American Journal Original research of Public Health 02 03 04 05 06 Socioeconomic factors associated with antimicrobial 07 08 resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 09 10 Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli in Chilean 11 12 hospitals (2008–2017) 13 14 15 Kasim Allel,1 Patricia García,2 Jaime Labarca,3 José M. Munita,4 Magdalena Rendic,5 Grupo 16 6 5 17 Colaborativo de Resistencia Bacteriana, and Eduardo A. Undurraga 18 19 20 21 Suggested citation Allel K, García P, Labarca J, Munita JM, Rendic M; Grupo Colaborativo de Resistencia Bacteriana; et al. Socioeconomic fac- 22 tors associated with antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli in 23 Chilean hospitals (2008–2017). Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e30. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.30 24 25 26 27 ABSTRACT Objective. To identify socioeconomic factors associated with antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeru- 28 ginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli in Chilean hospitals (2008–2017). 29 Methods. We reviewed the scientific literature on socioeconomic factors associated with the emergence and 30 dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. Using multivariate regression, we tested findings from the literature drawing from a longitudinal dataset on antimicrobial resistance from 41 major private and public hospitals and 31 a nationally representative household survey in Chile (2008–2017). We estimated resistance rates for three pri- 32 ority antibiotic–bacterium pairs, as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 33 i.e., imipenem and meropenem resistant P. aeruginosa, cloxacillin resistant S. aureus, and cefotaxime and 34 ciprofloxacin resistant E. coli. 35 Results. -

The Use of Bactericides in Plant Agriculture with Reference to Use in Ci

The Use of Bactericides in Plant Agriculture with Reference to Use in Ci... http://citrusrdf.org/use_of_bactericides_in_plant_ag_2016-02-04#more-4047 … Stephanie L. Slinski, Ph.D., Bactericide Project Manager, CRDF February 2016 The purpose of this communication is to discuss the use of bactericides in plant agriculture to control disease epidemics and the approaches that have been tested to control Huanglongbing (HLB) in citrus trees. The Citrus Research and Development Foundation (CRDF) has made this topic a priority in responding to HLB in Florida citrus. HLB is a disease devastating the citrus industry in Florida and throughout the world. Presently, no chemical treatment or resistant plant is available that will control the disease. For the Florida citrus industry to survive this epidemic, a chemical control will be necessary to suppress the disease, keeping the trees in production until groves can be replanted with resistant or tolerant varieties. This is similar to approaches taken during plant disease epidemics in other crops, which were eventually controlled by the planting of resistant varieties. Oxytetracycline, streptomycin sulfate and copper have been the main chemicals available to treat bacterial plant diseases in the US. The use of copper is limited to foliar diseases in regions where copper resistance is not widespread. Streptomycin and oxytetracycline are routinely used on some crops when copper is inadequate. Oxytetracycline has also often been used in the past to help manage plant disease epidemics. Research using bactericides on citrus suggests that chemical control may improve citrus tree health and contribute to sustaining the citrus industry in the current epidemic. Introduction The disease HLB has been known in many regions of the world for over a century. -

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Issues in the Treatment of Bacterial Infectious Diseases

Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2004) 23: 271–288 DOI 10.1007/s10096-004-1107-7 Complete Table of Contents CURRENT TOPIC: REVIEW Subscription Information for P. S. McKinnon . S. L. Davis Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Issues in the Treatment of Bacterial Infectious Diseases Published online: 10 March 2004 # Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract This review outlines some of the many factors a gies to optimize antibiotic selection and dosing remain at clinician must consider when selecting an antimicrobial the forefront of our clinical research today. dosing regimen for the treatment of infection. Integration The appropriate use of antimicrobial agents requires an of the principles of antimicrobial pharmacology and the understanding of the characteristics of the drug, the host pharmacokinetic parameters of an individual patient factors, and the pathogen, all of which impact selection of provides the most comprehensive assessment of the the antibiotic agent and dose. Figure 1 illustrates the interactions between pathogen, host, and antibiotic. For complexity of the multiple interactions between the each class of agent, appreciation of the different patient, the pathogen, and the antibiotic. Characteristics approaches to maximize microbial killing will allow for of the patient that must be considered include those that optimal clinical efficacy and reduction in risk of develop- affect the interaction between the patient and the infection, ment of resistance while avoiding excessive exposure and such as comorbid factors and underlying immune status, as minimizing risk of toxicity. Disease states with special well as patient-specific factors such as organ function and considerations for antimicrobial use are reviewed, as are weight, which will impact the pharmacokinetics of the situations in which pathophysiologic changes may alter antibiotic. -

The Antimicrobial Agent Fusidic Acid Inhibits Organic Anion Transporting

DMD Fast Forward. Published on February 17, 2016 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.115.067447 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. DMD # 67447 The Antimicrobial Agent Fusidic Acid Inhibits Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide-Mediated Hepatic Clearance and may Potentiate Statin-Induced Myopathy Heather Eng, Renato J. Scialis, Charles J. Rotter, Jian Lin, Sarah Lazzaro, Manthena V. Varma, Li Di, Bo Feng, Michael West, and Amit S. Kalgutkar Downloaded from Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Metabolism Department – New Chemical Entities, dmd.aspetjournals.org Pfizer Inc., Eastern Point Road, Groton, CT (H.E., R.J.S., C.J.R., J.L., S.L., M.V.V., L.D., B.F., M.W.) and Cambridge MA (A.S.K.) at ASPET Journals on September 30, 2021 1 DMD Fast Forward. Published on February 17, 2016 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.115.067447 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. DMD # 67447 Running Title: Drug-Drug interaction between statins and fusidic Acid Address correspondence to: Amit S. Kalgutkar, Pharmacokinetics, Dynamics, and Metabolism-New Chemical Entities, Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, 610 Main Street, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. Tel: +(617)-551-3336. E-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from Text Pages (including references): 38 Tables: 1 dmd.aspetjournals.org Figures: 5 References: 79 at ASPET Journals on September 30, 2021 Abstract: 247 Introduction: 624 Discussion: 1594 2 DMD Fast Forward. Published on February 17, 2016 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.115.067447 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. -

Evaluation of Several Bactericides As Seed Treatments for the Control of Black Rot of Crucifers and Studies on an Antibacterial Substance from Cauliflower Seed

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1962 Evaluation of Several Bactericides as Seed Treatments for the Control of Black Rot of Crucifers and Studies on an Antibacterial Substance From Cauliflower Seed. (Parts I and II). Fereydoon Malekzadeh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Malekzadeh, Fereydoon, "Evaluation of Several Bactericides as Seed Treatments for the Control of Black Rot of Crucifers and Studies on an Antibacterial Substance From Cauliflower Seed. (Parts I and II)." (1962). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 787. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/787 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 63—2781 microfilmed exactly as received MALEKZADEH, Fereydoon, 1933- EVALUATION OF SEVERAL BACTERICIDES AS SEED TREATMENTS FOR THE CONTROL OF BLACK ROT OF CRUCIFERS AND STUDIES ON AN ANTIBACTERIAL SUBSTANCE FROM CAULI FLOWER SEED. (PARTS I AND II). Louisiana State University, Ph.D.,1962 Agriculture, plant pathology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan EVALUATION OF SEVERAL BACTERICIDES AS SEED TREATMENTS FOR THE CONTROL OF BLACK ROT OF CRUCIFERS AND STUDIES ON AN ANTIBACTERIAL SUBSTANCE FROM CAULIFLOWER SEED A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Botany and Plant Pathology by Fereydoon Malekzadeh B.Sc., University of Teheran, 1956 M .Sc., University of Teheran, 1958 August, 1962 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation and gratitude to Dr.