Attracting Good People Into Public Service: Evidence from a Field Experiment in the Philippines∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippines: Information on the Barangay and on Its Leaders, Their

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 19 September 2003 PHL41911.E Philippines: Information on the barangay and on its leaders, their level of authority and their decision-making powers (1990-2003) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa A Cultural Attache of the Embassy of the Philippines provided the attached excerpt from the 1991 Local Government Code of the Philippines, herein after referred to as the code, which describes the role of the barangay and that of its officials. As a community-level political unit, the barangay is the planning and implementing unit of government policies and activities, providing a forum for community input and a means to resolve disputes (Republic of the Philippines 1991, Sec. 384). According to section 386 of the code, a barangay can have jurisdiction over a territory of no less than 2,000 people, except in urban centres such as Metro Manila where there must be at least 5,000 residents (ibid.). Elected for a term of five years (ibid. 14 Feb. 1998, Sec. 43c; see the attached Republic Act No. 8524, Sec. 43), the chief executive of the barangay, or punong barangay enforces the law and oversees the legislative body of the barangay government (ibid. 1991, Sec. 389). Please consult Chapter 3, section 389 of the code for a complete description of the roles and responsibilities of the punong barangay. In addition to the chief executive, there are seven legislative, or sangguniang, body members, a youth council, sangguniang kabataan, chairman, a treasurer and a secretary (ibid., Sec. -

Imperialist Campaign of Counter-Terrorism

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. LII No. 11 June 7, 2021 www.cpp.ph 9 NPA offensives in 9 days VARIOUS UNITS OF the New People's Army (NPA) mounted nine tactical offensives in the provinces of Davao Oriental, Quezon, Occidental Mindoro, Camarines Sur, Northern Samar at Samar within nine days. Six‐ teen enemy troopers were killed while 18 others were wounded. In Davao Oriental, the NPA ambushed a military vehicle traversing the road at Sitio Tagawisan, Badas, Mati City, in the morning of May 30. Wit‐ nesses reported that two ele‐ EDITORIAL ments of 66th IB aboard the vehicle were slain. The offensive was launched just a kilometer Resist the scheme away from a checkpoint of the PNP Task Force Mati. to perpetuate In Quezon, the NPA am‐ bushed troops of the 85th IB in Duterte's tyranny Barangay Batbat Sur, Buenavista on June 6. A soldier was killed odrigo Duterte's desperate cling to power is a manifestation of the in‐ and two others were wounded. soluble crisis of the ruling semicolonial and semifeudal system. It In Occidental Mindoro, the Rbreeds the worst form of reactionary rule and exposes its rotten core. NPA-Mindoro ambushed joint It further affirms the correctness of waging revolutionary struggle to end the operatives of the 203rd IBde and rule of the reactionary classes and establish people's democracy. police aboard a military vehicle at Sitio Banban, Nicolas, A few months prior to the 2022 ties and dictators. Magsaysay on May 28. The said national and local elections, the This maneuver is turning out to unit was on its way to a coun‐ ruling Duterte fascist clique is now be Duterte's main tactic to legalize terinsurgency program in an ad‐ busy paving the way to perpetuate his stay in power beyond the end of jacent barangay, along with its tyrannical rule. -

'14 Sfp -9 A10 :32

Srt1lltr SIXTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC (fJff1;t t,f t~t !~rrrvf:1f\l OF THE PHILIPPINES Second Regular Session '14 SfP -9 A10 :32 SENATE Senate Bill No. 2401 Prepared by the Committees on Local Government; Electoral Reform~ ang People's 'J, . ..... Participation; Finance; and Youth with Senators Ejercito, Aquino IV, Marcos Jr., Pimentel III, and Escudero, as authors thereof AN ACT ESTABLISHING ENABLING MECHANISMS FOR MEANINGFUL YOUTH PARTICIPATION IN NATION BUILDING, STRENGTHENING THE SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN, CREATING THE MUNICIPAL, CITY AND PROVINCIAL YOUTH DEVELOPMENT COUNCILS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Be it enacted by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled: 1 CHAPTER I 2 INTRODUCTORY PROVISIONS 3 Section 1, Title. - This Act shall be known as the "Youth Development 4 and Empowerment Act of 2014". 5 Section 2. Declaration of State Policies and Objectives. - The State 6 recognizes the vital role of the youth in nation building and thus, promotes 7 and protects their physical, moral, spiritual, intellectual and social well- 8 being, inculcates in them patriotism, nationalism and other desirable 9 values, and encourages their involvement in public and civic affairs. 10 Towards this end, the State shall establish adequate, effective, 11 responsive and enabling mechanisms and support systems that will ensure 12 the meaningful participation of the youth in local governance and in nation 13 building. 1 1 Section 3. Definition of Terms. - For purposes of this Act, the 2 following terms are hereby defined: 3 (a) "Commission" shall refer to the National Youth Commission 4 created under Republic Act (RA) No. -

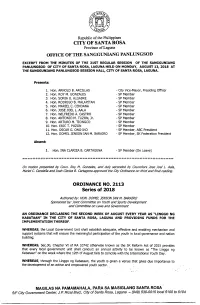

ORDINANCE NO. 2113 Series of 2018

sANti 1„, Republic of the Philippines CITY OF SANTA ROSA Province of Laguna OFFICE OF THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE 31ST REGULAR SESSION OF THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD OF CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA HELD ON MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 AT THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD SESSION HALL, CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA. Presents: 1. Hon. ARNOLD B. ARCILLAS - City Vice-Mayor, Presiding Officer 2. Hon. ROY M. GONZALES - SP Member 3. Hon. SONIA U. ALGABRE - SP Member 4. Hon. RODRIGO B. MALAPITAN - SP Member 5. Hon. MARIEL C. CENDANA - SP Member 6. Hon. JOSE JOEL L. AALA - SP Member 7. Hon. WILFREDO A. CASTRO - SP Member 8. Hon. ANTONIO M. TUZON, Jr. - SP Member 9. Hon. ARTURO M. TIONGCO - SP Member 10.Hon. ERIC T. PUZON - SP Member 11.Hon. OSCAR G. ONG-IKO - SP Member, ABC President 12.Hon. DOMEL JENSON IAN M. BARAIRO - SP Member, SK Federation President Absent: 1. Hon. INA CLARIZA B. CARTAGENA - SP Member (On Leave) On motion presented by Coun. Roy M. Gonzales, and duly seconded by Councilors Jose Joel L. Aala, Mariel C. Cendafia and Inah Clariza B. Cartagena approved the City Ordinance on third and final reading. ORDINANCE NO. 2113 Series of 2018 Authored by: HON. DOMEL JENSON IAN M. BARAIRO Sponsored by: Joint Committee on Youth and Sports Development and Committee on Laws and Government AN ORDINANCE DECLARING THE SECOND WEEK OF AUGUST EVERY YEAR AS "LINGGO NG KABATAAN" IN THE CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA AND PROVIDING FUNDS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION THEREOF. WHEREAS, the Local Government Unit shall establish adequate, effective and enabling mechanism and support systems that will ensure the meaningful participation of the youth in local governance and nation building; WHEREAS, Sec.30, Chapter VI of RA 10742 otherwise known as the SK Reform Act of 2015 provides that every local government unit shall conduct an annual activity to be known as "The Linggo ng Kabataan" on the week where the 12th of August falls to coincide with the International Youth Day. -

LOCAL BUDGET MEMORANDUM No, 80

LOCAL BUDGET MEMORANDUM No, 80 Date: May 18, 2020 To : Local Chief Executives, Members of the Local Sanggunian, Local Budget Officers, Local Treasurers, Local Planning and Development Coordinators, Local Accountants, and AU Others Concerned Subject : INDICATIVE FY 2021 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT (IRA) SHARES OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS (LGUs) AND GUIDELINES ON THE PREPARATION OF THE FY 2021 ANNUAL BUDGETS OF LGUs Wiifl1s3ii 1.1 To inform the LGUs of their indicative IRA shares for FY 2021 based on the certification of the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) on the computation of the share of LGUs from the actual collection of national internal revenue taxes in FY 2018 pursuant to the Local Government Code of 1991 (Republic Act [RA] No. 7160); and 1.2 To prescribe the guidelines on the preparation of the FY 2021 annual budgets of LGUs. 2.0 GUIDELINES 2.1 Allocation of the FY 2021 IRA 2.1.1 In the computation of the IRA allocation of LGUs, the following factors are taken into consideration: 2.1.1J FY 2015 Census of Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay, as approved through Proclamation No. 1269 dated May 19, 2016;1 and 2.1.1,2 FY 2001 Master List of Land Area certified by the Land Management Bureau pursuant to Oversight Committee on Devolution Resolution No, 1, s. 2005 dated September 12, 2005. Declaring as Official the 2015 Population of the Philippines by Province, City/Municipality, and Barangay, Based on the 2015 Census of Population Conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority Page 1 1 2.1.2 The indicative FY 2021 IRA shares of the individual LGUs were computed based on the number of existing LGUs as of December 31, 2019. -

Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy?

WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT RIZALINO S. NAVARRO POLICY CENTER FOR COMPETITIVENESS WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness AUGUST 2015 The authors would like to thank retired Associate Justice Adolfo Azcuna, Dr. Florangel Rosario-Braid, and Dr. Wilfrido Villacorta, former members of the 1986 Constitutional Commission; Dr. Bruno Wilhelm Speck, faculty member of the University of São Paolo; and Atty. Ray Paolo Santiago, executive director of the Ateneo Human Rights Center for the helpful comments on an earlier draft. This working paper is a discussion draft in progress that is posted to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asian Institute of Management. Corresponding Authors: Ronald U. Mendoza, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] Jan Fredrick P. Cruz, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 1. Introduction Political dynasties, simply defined, refer to elected officials with relatives in past or present elected positions in government. -

The Barangay Justice System in the Philippines: Is It an Effective Alternative to Improve Access to Justice for Disadvantaged People?

THE BARANGAY JUSTICE SYSTEM IN THE PHILIPPINES: IS IT AN EFFECTIVE ALTERNATIVE TO IMPROVE ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR DISADVANTAGED PEOPLE? Dissertation for the MA in Governance and Development Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex By Silvia Sanz-Ramos Rojo September 2002 Policy Paper SUMMARY This paper will analyse the Barangay Justice System (BJS) in the Philippines, which is a community mediation programme, whose overarching objective is to deliver speedy, cost-efficient and quality justice through non-adversarial processes. The increasing recognition that this programme has recently acquired is mainly connected with the need to decongest the formal courts, although this paper will attempt to illustrate the positive impact it is having on improving access to justice for all community residents, including the most disadvantaged. Similarly, the paper will focus on link between the institutionalisation of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) and the decentralisation framework in the country. It will discuss how the challenging devolution of powers and responsibilities from the central government to the barangays (village) has facilitated the formal recognition of the BJS as an alternative forum for the resolution of family and community disputes. Moreover, the paper will support the idea that dispute resolution is not autonomous from other social, political and economic components of social systems, and will therefore explore how the BJS actually works within the context of the Philippine society. Thus, the analysis will be based on the differences between how the BJS should work according to the law and how it really operates in practice. It will particularly exhibit the main strengths and limitations of the BJS, and will propose certain recommendations to overcome the operational problems in order to ensure its effectiveness as an alternative to improve access to justice for the poor. -

Conflict of Interest and Good Governance in the Public Sector — Looking at the Private Interests of Government Officials Within a Spectrum

Conflict of Interest and Good Governance in the Public Sector — Looking at the Private Interests of Government Officials Within a Spectrum MARY JUDE CANTORIAS MARVEL* Introduction A discussion of good governance principles is timely amidst the backdrop of the coming Philippine elections. Patronage has always played a key role in Philippine politics and it may be wishful thinking to believe that the electorate will, this time around, choose their elected government officials based on platform and not on “who-can-give-the-most-dole-outs” but one can hope. Philippine local elections tend to be prone to dole outs in that, at the grass roots level, the public look to their locally elected politicians as direct sources of funding to spend on the town fiesta, a wedding, a funeral, building a make-shift basketball court where the town’s people can play a round of hoops to distract the unemployed, ad infinitum. This popular concept in politics has been named the “patron- client relations framework,” as defined in a study conducted by the Institute for Political and Electoral Reform: In this framework, political leaders who are of a higher socio-economic status (patron), acquire power by providing material benefits to people of lower status (client), who in turn, commit their votes to the patron during elections. Electoral exercises are often oriented to * The author is an alumna of the Arellano University School of Law (AUSL). In 2010, she received her degree in Master of Laws in Dispute Resolution from the University of Missouri-Columbia under a Rankin M. Gibson LL.M. -

![[ Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act No. 257]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7032/muslim-mindanao-autonomy-act-no-257-1947032.webp)

[ Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act No. 257]

RA BILL No. 10 Republic of the Philippines Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao REGIONAL ASSEMBLY Cotabato City SIXTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (First Regular Session) [ MUSLIM MINDANAO AUTONOMY ACT NO. 257] Begun and held in Cotabato City, on Monday, the twenty-sixth day of October, two thousand and nine. AN ACT CREATING BARANGAY BAHAN IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF TUBURAN, PROVINCE OF BASILAN, INTO A DISTINCT, SEPARATE AND INDEPENDENT BARANGAY, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. Be it enacted by the Regional Assembly in session assembled: Section 1. Sitio Bahan is hereby separated from its mother Barangay and constituted into a distinct and independent Barangay to be known as Barangay Bahan in the Municipality of Tuburan, Province of Basilan. Sec. 2. As created, Barangay Bahan shall be bounded by natural and duly designated boundaries, more specifically described as follows: LINE BEARINGS DISTANCES TP - 1 N - 24° 17 - W 26.990.55m 2 S - 38° 34 - E 7300.00m 3 S - 75° 45 - W 3000.00m 4 N - 29° 02 - W 2555.64m 5 N - 21° 33 - W 1148.63m 6 N - 61° 37 - W 1118.71m 7 N - 24° 30 - W 1922.71m 7 1 N - 64° 25 - E 1995.93m Sec. 3. The corporate existence of this barangay shall commence upon the appointment of its Punong Barangay and majority of the members of the Sangguniang Barangay, including the Sangguniang Kabataan. Page 2 MMA 257 SEC. 4. The Mayor of the Municipality of Tuburan shall appoint the Punong Barangay and seven (7) members of the Sangguniang Barangay, including the Chairman and seven (7) members of the Sangguniang Kabataan, immediately after the ratification of this Act. -

Governance of the Barangay Chairpersons in the Municipality of Ubay Bohol

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES Vol 9, No 1, 2017 ISSN: 1309-8047 (Online) GOVERNANCE OF THE BARANGAY CHAIRPERSONS IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF UBAY BOHOL Sheena L. Boysillo, MPA Holy Name University Governance of the Barangay Chairpersons in the Municipality of Ubay Bohol [email protected] ─Abstract ─ Barangay governance plays a vital role in the empowerment of the local government units in the country. This is linked with the leader’s accountability, fairness, and transparency in the exercise of his duties and functions as a servant in his community. This study aimed to evaluate the governance of the Barangay Chairpersons in the Municipality of Ubay, Bohol. The researcher employed the descriptive survey questionnaire using quantitative design and a key informant interview using a qualitative approach. Results showed that the higher the IRA (Internal Revenue Allotment) given to the barangays, the more programs and projects are implemented because funds had been given to them as a subsidy for continuous developments. The results also indicated that majority of the Barangay Chairpersons were able to deliver very satisfactory public services in their barangays which also indicated that the core values of governance namely fairness, transparency and accountability were strengthened by the barangay chairmen during their term of office. The study concluded that the Local Government Code of 1991 paved the way for greater local autonomy to bring government closer to the doorsteps of the people. Key Words: Governance, Accountability, Fairness, Transparency JEL Classification: Z00 50 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES Vol 9, No 1, 2017 ISSN: 1309-8047 (Online) 1. -

Position Classification and Compensation Scheme in Local Government Units

Chapter 9 Position Classification and Compensation Scheme in Local Government Units 9.1 Historical Background 9.1.1 Before Presidential Decree (PD) No. 1136 Local governments are political units composed of provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays. They have long been existing with their own legislative bodies which are endowed with specific powers as defined in the Revised Administrative Code and individual local government unit (LGU) charters. These local legislative bodies were then called provincial boards in the case of provinces, city councils in cities and municipal councils in municipalities. These local legislative bodies were vested with the power to determine the number of employees that each office should have and to fix their salary rates as agreed upon by the majority. In exercising such power, however, there were no specific guidelines nor definite standards used in the creation of positions and the fixing of salaries. Position titles were not descriptive nor reflective of the duties and responsibilities of the positions and salaries were fixed arbitrarily. For local officials, however, laws such as Republic Act (RA) No. 268 as amended, and RA No. 4477 were passed by Congress fixing the salaries of municipal, provincial and city officials. These salary laws created a wide gap between the salaries of rank-and-file employees and the officials. 9.1.2 PD No. 1136 Cognizant of the need for a more effective local government personnel administration, PD No. 1136, “The Local Government Personnel Administration and Compensation Plans Decree of 1977,” was promulgated on May 5, 1977. Its salient features are as follows: 9.1.2.1 The creation of the Joint Commission on Local Government Personnel Administration (JCLGPA) to formulate policies on local government personnel administration, position classification and pay administration; and to implement the provisions of PD No. -

A Documentation of the 10-Point Checklist for Making San Francisco, Camotes Resilient to Disasters

A Documentation of the 10-Point Checklist for Making San Francisco, Camotes Resilient to Disasters Sasakawa Award Nomination Submission February 2011 Municipal Profile The Municipality of San Francisco, which is among the four municipalities that constitute the Camotes Group of Islands in Central Philippines, has high vulnerability to multiple geohazards. Such hazards include typhoons, floods, landslide and strong monsoon winds. Moreover, communities are also vulnerable to fires as most houses are made of light materials. As a third class municipality, San Francisco faces an additional challenge of the economic impacts of calamities and disasters. With a population mainly dependent on the sea and land for sustenance, strong winds and heavy rains greatly affect their ability to pursue their respective livelihoods especially in fishing and farming. Being an island municipality, access to supplies from the mainland of Cebu Province is made more difficult during stormy weather, thus aggravating the vulnerabilities of the people of San Francisco. Figure 1. Profile Map of the Municipality of San Francisco Figures 2-8. Municipal Hazard Maps Common hazards that affect communities Flooding Typhoons and Monsoon Winds Given their high vulnerability to multiple hazards, the Municipality of San Francisco believes that making their island resilient to disaster is an important agenda for the Local Government. And key to building resilience is empowering people through providing the environment for communities to create local and practical solutions to achieve Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) objectives. The Ten Point Essentials: San Francisco is getting ready Essential # 1: Put in place organization and coordination to clarify everyone’s roles and responsibilities.