Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity, by Erynn Masi De Casanova Trenton M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convertible Collar Construction

Convertible Collar Construction Directory Click any image to go to that section Yoke/Facing Options: Intro and Gallery By far the most common set-up for a The purpose of this introductory section is to convertible-collar shirt is that it has front facings feature and compare the range of other options and a yoke, and that these two details don’t touch, also, if less commonly, in use beyond this classic as in the example at right. one, before I proceed to work step-by-step through a handful of useful variants . Many other possible That is, the facings don’t extend far enough combinations, and of course, variations on the towards the shoulders at the neckline that they’ll ones here, are conceiveable and may suit your meet with or join to the fronts of the yoke layers. As project better, so feel free to experiment. a result, the yoke construction steps aren’t integrated into the collar steps and are completed, in front at least, before the collar is begun, so the options for using the yoke as a back facing are eliminated. The steps for this classic arrangement are described below in Variation #5, in the Front Facing Only category. Collar Insertion Options Step-By-Step No Yoke or Facings Required Front facings Only Front and Back Facings, or Yoke Used as Facing Variation 1: Collar Applied as Band Variation 3: Collar’s Back Neckline Edge-Stitched Variation 6: Back Facings 1 3 and Facings Secured at Shoulder Seams 6 Options: Options: 1. Edge-stitched neckline 2. -

ALDI Textiles

ALDI Textiles ALDI Textiles Guideline 2 Aloe Vera. Recognises the demand all on its own. A Aloe vera micro capsules are attached to the textile fibres using a binder. The friction from wearing causes the microcapsules to burst and release the moisturising substance. The advantage of the microcapsules is the fact that the encapsulated substance is only released when the fabric is mechanically stressed. Through the addition of the aloe vera capsules, the garment hydrates and moisturises the skin. Anti-Pilling. Reduces pilling. A Anti-pilling is a special finishing process for reducing the formation of pilling, meaning lint, in predominantly synthetic materials. This is primarily achieved through a mechanical process or heat treatment. ALDI Textiles Guideline 3 Breathable. Keeps you dry and keeps moisture away. B Breathable fabrics are defined as textiles which possess certain physiological properties which above all wick moisture away from the skin. Such materials may also be water-resistant and therefore protect against rain. See also: Cool & Fresh, COOLMAX® ALDI Textiles Guideline 4 Cotton. The all-rounder among textiles. C Cotton is derived from the soft seed hair of the cotton plant. The plant thrives in countries with a sub-tropical climate, such as the USA, Egypt, India, and South Africa, and in terms of volume is one of the most important raw textiles materials in the world. The quality of cotton wool is dependent on its fineness, strength, fibre length and consistency. See also: Wool, virgin wool, organic cotton, Pima cotton PROPERTIES: It is skin-friendly: Due to its softness, it is very pleasant on the skin. -

Tailoring Series TECHNIQUES for TAILORING UNDERLINING a TAILORED GARMENT—Underlining Is a Second Layer of Fabric. It Is Cut By

tailoring series TECHNIQUES FOR TAILORING UNDERLINING A TAILORED GARMENT—Underlining is a second layer of fabric. It is cut by the garment pattern pieces and staystitched to the wrong side of the corresponding outer sections before any seams are joined. The two layers are then handled as one. As a general guide, most suit jackets and coats look more pro- fessional when underlined. Underlining is especially recommended for lightweight wool materials, loosely woven materials and light- colored materials. For additional information on selecting fabrics for underlining and applying the underlining, see Lining a Shirt 01' Dress HE 72, N. C. Agricultural Extension Service. STAYSTITCHING—Staystitch all outer garment pieces before construction begins. If garment is underlined, stays-titching is done when the two layers of fabric are sewn together. Staystitch 1/3 in. outside seamline (on the seam allowance). Stay- stitch “ with matching cotton thread on all curved *areas that may stretch during construction such as necklines, side seams, shoulder seams, armholes, and side seams of skirt. Use directional stitching always to prevent stretching of fabric and to prevent one layer of fabric from riding. The direction to stitch is indicated by small arrows on the pattern on the seamlines. INTERFACINGS—Select a high quality hair canvas for the front and collar of coats and jackets. The percentage of wool indicates the quality—the higher the wool content of the canvas the better the quality. Since a high percentage of wool makes the hair canvas fairly dark in color, it cannot be used successfully under light-colored fabrics. In these cases use an interfacing lighter in color and lower in wool content. -

Drafting Collars

DRAFTING COLLARS Excerpted from GERTIE’S NEW BOOK FOR BETTER SEWING GERTIE’S NEW BOOK FOR BETTER SEWING A MODERN GUIDE TO COUTURE-STYLE SEWING USING BasIC VINTagE TECHNIQUES GRETCHEN HIRSCH Photographs by Jody Rogac Illustrations by Sun Young Park Available wherever books are sold. find out more at melaniefalickbooks.com Copyright © Gertie's New Book for Better Sewing by Gretchen Hirsch, published by STC Craft | Melanie Falick Books, an imprint of ABRAMS, 2012. DRAFTING COLLARS ADJUSTMENT FOR PETER PAN COLLAR Collars can also be drafted from scratch and added to your blouse and dress patterns. My favorite vintage-style collar is the Peter Pan collar, which I incorporated into the blouse variation on page 160. It can be added to any blouse, jacket, or dress with a round neckline, and it will make the most basic garment ooze charm! Depending on how you style a Peter Pan collar, it can look ladylike or playful, 1930s glam or 1960s mod. Once you understand the basics of making a Peter Pan collar, you can apply this knowledge to any shape or size collar you like. For the purpose A. Overlap shoulder seams. of this little design project, let’s use a 1940s button-back blouse as our base. The basic premise of drafting a collar like this is that you use the neckline of your garment as your guide—the basic shape of your collar is right there! So start by laying out your blouse front and back pattern pieces on a table. Use a colored pencil to draw in the neckline and shoulder seam lines on your pattern pieces. -

Price List MORNINGWEAR LOUNGE SUITS

ADDITIONAL ITEMS Item Details Price CUFFLINKS / CRAVAT PIN (With packages) £6 / €8 Add a taller top hat to any Morning Suit Package £30 / €42 TOP HATS Add a grey or black top hat to any Morning Suit Package £20 / €28 SHOES Formal shoes in adult sizes 6-13 to hire with any outfit £20 / €28 ACCESSORIES PACK Waistcoat, shirt and cravat or tie (1 week’s hire) £40 / €56 JUNIOR ACCESSORIES PACK Waistcoat, shirt and cravat or tie (1 week’s hire) £35 / €49 STUDENT DISCOUNT Student discounts are available for graduation balls and schools proms. Please speak to a member of staff for more details. EXTENDED HIRE If you are getting married abroad we can arrange extended hire or you can collect your suit from us a week early. Ask in store for details on our extended hire options and prices. INSTANT HIRE Many of our stores hold a range of eveningwear available for instant hire. Where instant hire is not possible we will always endeavour to meet your requirements, however a carriage charge may be required. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION MOSS BESPOKE All prices relate to weekend hire. Prices and package contents are Moss Bespoke offers a bold new approach to men’s tailoring – correct at the time of going to print although may be subject to crafted by you, to suit your style and personality. subsequent change. At the heart of Moss Bespoke is customisation; as simple as 1-2-3. Obtaining Peace Of Mind Assurance at an additional cost of £9.00 / €12 will exclude the customer’s accidental damage liability Select your cut, choose the fabric that fits the occasion for the maximum value of the goods hired (excluding tops hats). -

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition Introduction There does not seem to have been any distinctive everyday dress for Christian pastors up until the 6th century or so. Clergy simply wore what was common, yet muted, modest, and tasteful, in keeping with their office. In time, however, the dress of pastors remained rather conservative, as it is want to do, while the dress of lay people changed more rapidly. The result was that the dress of Christian pastors became distinct from the laity and thus that clothing began to be invested (no pun intended) with meaning. Skipping ahead, due to the increasing acceptance of lay scholars in the new universities, the Fourth Lateran council (1215) mandated a distinctive dress for clergy so that they could be distinguished when about town. This attire became known as the vestis talaris or the cassock. Lay academics would wear an open front robe with a lirripium or hood. It is interesting to note that both modern day academic and clerical garb stems from the same Medieval origin. Councils of the Roman Catholic church after the time of the Reformation stipulated that the common everyday attire for priests should be the cassock. Up until the middle of the 20th century, this was the common street clothes attire for Roman Catholic priests. The origin of the clerical collar does not stem from the attire of Roman priests. It’s genesis is of protestant origin. The Origin of Reformed Clerical Dress In the time of the Reformation, many of the Reformed wanted to distance themselves from what was perceived as Roman clerical attire. -

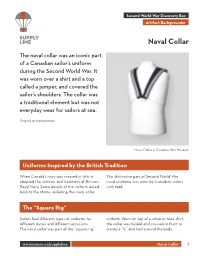

AB3.1 Naval Collar

Second World War Discovery Box Artifact Backgrounder Naval Collar The naval collar was an iconic part of a Canadian sailor’s uniform during the Second World War. It was worn over a shirt and a top called a jumper, and covered the sailor’s shoulders. The collar was a traditional element but was not everyday wear for sailors at sea. Original or reproduction Naval Collar © Canadian War Museum Uniforms Inspired by the British Tradition When Canada’s navy was created in 1910, it This distinctive part of Second World War adopted the uniform and traditions of Britain’s naval uniforms was worn by Canadian sailors Royal Navy. Some details of the uniform dated until 1968. back to the 1800s, including the naval collar. The “Square Rig” Sailors had different types of uniforms for uniform. Worn on top of a white or blue shirt, different duties and different occasions. the collar was folded and crossed in front to The naval collar was part of the “square rig” create a “V,” and tied around the body. warmuseum.ca/supplyline Naval Collar 1 The sailor wore a jumper over the shirt, The “square rig” uniform was often worn arranging the naval collar to lay over the ashore, and for ceremonies, religious services back. The uniform also included a black and funerals. In the wartime Royal Canadian silk neckerchief, bell-bottom trousers and a Navy, everyday sailors’ outfits were usually rating’s cap. Higher-ranking naval personnel, more functional, including sweaters, denim including officers, did not wear jumpers shirts and trousers, and waterproof clothing. -

Download the Full Glossary of Terms

Glossary of Terms Term Description # (number) 1x1 Rib Knit A rib knit is produced using a style of knitting pattern which yields a distinct vertically ridged pattern known as ribbing. A 1x1 Rib knit is created when the rows of the "knit" and "purl" stitch are identical. 2-Way Zipper A zipper with two zipper pulls so the garment can be unzipped from either direction. 2x1 Rib Knit A rib knit is produced using a style of knitting pattern which yields a distinct vertically ridged pattern known as ribbing. A 2x1 Rib knit is created when there are two rows a "knit" stitch and one row of a "purl" stitch. 2-Needle Stitching See Double-Needle Stitching 4-Needle Stitching A finish commonly used on a sleeve or bottom hem that uses four needles to create parallel rows of visible stitching, giving the garment a cleaner, more finished look, as well as adding 50/50 50-percentdurability. cotton/50-percent polyester fabric; also referred to as "poly/cotton". A Air Jet Yarn A spinning technology which spins a single type of yarn or with a blend of filament yarns which provide for a virtually "pill free" fabric Allen Solley Placket A one-piece placket that's hidden after being sewn. This process utilizes the existing fabric for the outside placket face. ANSI The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is an organization that promotes standards for industry and government. Most often refers to safety colors. Anti-Bacterial A finish or treatment that inhibits the growth of bacteria. Anti-Microbial A term used for a garment that is able to resist, either naturally or chemically, the effects of microbial secretions put off by the human body, resisting odor and increasing garment life. -

Men Clergy Shirts, Collars & Accessories

Men Clergy Shirts, Collars & Accessories (ask about discount on bulk orders) To Place Your Order Call 301-333-8009 or email: [email protected] Wanda Childs CEO/President of two companies (Blessed 24:7 Gift Shop) and (Printing Express & Designs, LLC) Tab Collar Clergy Shirt SM101 Affordably priced, this high quality clergy shirt is tailored in an easy care poly/cotton blend for wrinkle-resistant good looks. Tailoring details include: Comfortable, low-profile tab collar (includes reusable plastic tab insert) Generous full cut Front placket conceals 7 button closure Center back pleat Left front pocket Machine washable blend of 65% polyester and 35% cotton Full and half sizes 15 – 18 ½; Full sizes 19 – 21 15” 15 ½ “ 16” 16 ½ “ 17” 17 ½’ Neck 18” 18 ½” 19” 20” 21” $35.90 ea. Tab Collar Clergy Shirt SM104 * See Size Chart Below Tab collar convenience makes this black long-sleeve clergy shirt a wardrobe standard. Tailoring details include: Comfortable, low-profile tab collar (includes reusable plastic tab insert) Generous full cut Front placket conceals 7 button closure Center back pleat Adjustable 2 button mitered cuffs Buttoned sleeve plackets Left front pocket Full and half sizes 15 – 18, Machine washable blend of 65% polyester and with sleeve lengths 32/33, 35% cotton 34/35 and 36/37; Sizes 18 ½, 19, 20, 21 with sleeve lengths 34/35, 36/37 and 38/39 $41.90 ea Tab Collar Clergy Shirt SM109 Affordably priced, this high quality clergy shirt is tailored in an easy care poly/cotton blend for wrinkle-resistant good looks. Tailoring details include: Comfortable, low-profile tab collar (includes reusable plastic tab insert) Generous full cut Front placket conceals 7 button closure Center back pleat Left front pocket Machine washable blend of 65% polyester and 35% cotton 15” 15 ½ “ 16” 16 ½ “ 17” 17 ½’ Full and half sizes 15 – 18 ½; Neck 18” 18 ½” 19” 20” 21” Full sizes 19 – 21 $37.90 ea. -

80739083.Pdf

3-~"'81 8-1355 ~.(O~ All About ... • Pattern Selection • Fabric Selection • Contemporary Techniques • Fusible Interfacings • Finishing Tips CONTENTS Page Pattern Selection. ............................................... .. 3 Fabric Selection ................................................ .. 3 Notions. ....................................................... .. 3 Pressing Points ................................................. .. 4 Inner Fabrics. .................................................. .. 4 Underlining. ................................................. .. 4 Interfacing. .................................................. .. 4 Lining. ..................................................... .. 5 Preparation ............................................ .. 5 Fabric. ...................................................... .. 5 Pattern Fit. .................................................. .. 5 Cutting and Marking. ......................................... .. 5 Comparison of Custom and Contemporary Tailoring Techniques. ...... .. 5 Front and Back Interfacing. ...................................... .. 5 Fusible Method-Front. ...................................... .. 5 onfusible Method-Back Reinforcement. ....................... .. 6 One-Piece Method. ........................................ .. 6 Two-Piece Method ......................................... .. 6 Applying Back Reinforcement .................................. .. 7 Lapel and Roll Line ............................................. .. 7 Marking the Roll Line , 8 Taping the -

Peter Pan Collar Project Sheets

PROJECT GUIDE EMBROIDERED PETER PAN COLLAR Supplies: - round embroidery hoop - cotton fabric 10” x 10” - fusible interfacing fabric - embroidery scissors - scissors - DMC embroidery needle size 3 - embroidery transfer pen - sewing thread - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 349 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 703 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 3042 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 311 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 605 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 892 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 597 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 799 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 726 - DMC Pearl Cotton n. 5 color 422 - ribbon STEP 1 Transfer the design to the cotton fabric (remember to iron your fabric first). STEP 2 Place the fabric into the hoop. With 1 strand of DMC Pearl Cotton thread, The new handmade brand brought to you by DMC embroider the peter pan collar design following www.Commonthread.us the pattern. Visit us on © 2016 The DMC Corporation STEP 3 Cut out 4 pieces (2 embroidered and 2 with no embroideries) of the cotton fabric following the pattern, remember you have to add the seam allowance. Cut 2 pieces of the fusible interfacing fabric (with no seam allowance). STEP 4 Place the fusible interfacing fabric on the 2 cotton pieces with no embroideries and iron. STEP 5 Pin the embroidered pieces right sides together and sew the center back seam. Pin the non embroidered pieces right sides together and sew the center back seam. Press seams open. STEP 6 Pin both pieces right sides together. Sandwich the ribbon in between the 2 layers making sure to only catch the edge of the ribbon in the corner seam Stitch all around the edges of the collar with a 1/2” seam allowance. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000