Economic Strategy That Can Help Guide Policies, Projects, and Investments for the Next Five Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

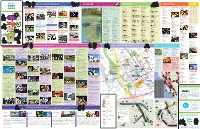

Downtown Walking

N Montgomery St Clinton Ct Autumn A B C D E F G H I J d v N Blv Stockton Av A Guadalupe Gardens n Mineta San José Market Center VTA Light Rail Japantown African Aut t North S 1 mile to Mountain View 1.1 miles ame 0.8 miles International Airport ne American u i m a D + Alum Rock 1 n 3.2 miles e Community t r Terr Avaya Stadium St S N Almade N St James Services th Not 2.2 miles Peralta Adobe Arts + Entertainment Whole Park 0.2 miles 5 N Foods Fallon House St James Bike Share Anno Domini Gallery H6 Hackworth IMAX F5 San José Improv I3 Market W St John St Little Italy W St John St 366 S 1st St Dome 201 S Market St 62 S 2nd St Alum Rock Alum Food + Drink | Cafés St James California Theatre H6 Institute of H8 San José G4 Mountain View 345 S 1st St Contemporary Art Museum of Art Winchester Bike Share US Post Santa Teresa 560 S 1st St 110 S Market St Oce Camera 3 Cinema I5 One grid square E St John St 288 S 2nd St KALEID Gallery J3 San José Stage Co. H7 Center for the E5 88 S 4th St 490 S 1st St represents approx. Trinity Performing Arts Episcopal MACLA/Movimiento H8 SAP Center B2 255 Almaden Blvd 3 minutes walk SAP Center n St Cathedral de Arte y Cultura Latino 525 W Santa Clara St San José Sharks | Music m Americana 510 S 1st St tu Children’s D7 Tabard Theatre Co. -

Spartan Daily

SEE FOOTBALL PAGE 8 SEE THESE VIDEOS AND MORE ON SPARTANDAILY ON YOUTUBE NO LOVE FOR SJSU IN IOWA FIRST HIP HOP RUN CITYDANCE SAN JOSE SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 SPARTAN DAILY Volume 147. Issue 121 www.sjsunews.com/spartandaily Tuesday,Wednesday, September August 24,27, 2016 LIVE ON THE LAWN MEDAL OF ARTS San Jose State alum honored BY SHELLISE WEST in many ways, our national soul. STAFF WRITER They’re central to who are are as President Barack Obama Americans.” said Obama. presented playwright, director Valdez, who attended SJSU and San Jose State University in 1960 began his career after alum Luis Valdez with the 2015 winning a playwright competition National Medal of Arts Thursday for his one-act play The Theft for his contribution to Chicano according to his biography. theatre and arts. Known for his work in Zoot The ceremony included notable Suit, he returned to the theatre journalists, authors, and directors department to put on a production lasted briefl y with an address from with students in the spring of 2015. President Barack Obama before The production that focused on RAYMOND BALTAZAR | SPARTAN DAILY honoring each awardee. Latino racial injustice in Los SEE FULL PHOTO ESSAY ON PAGE 4 “The arts and humanities are See VALDEZ page 3 TIME TO VOTE SWASTIKAS INSIDE Propositions occupy Off enders: Student Union Th eater ‘It was just a joke’ BY JASON DUNHAM Proposition 63 would also affect the large- STAFF WRITER capacity magazine ban from 2000. By extending the ban’s effect to purchases that BY ITZEL CASTRO California gun legislation and the death STAFF WRITER penalty were the focus of discussion at the were made before the original 2000 ban. -

Convention and Cultural District San José State University St James Park

N M o n t g o m e r y S t t Clin tumn C ton Au A B C D E F G H I J d v l v B N S A n Market Center VTA Light Rail t Guadalupe Gardens Mineta San José Japantown African A e t o e u S North c d m e k t a 1 mile to Mountain View 1.1 miles a 0.8 miles International Airport n American u t i o m a D m r l r + Alum Rock n 1 e n e A 3.2 miles Community t r A T Avaya Stadium t S S v N o St James t Services h t N 2.2 miles 5 Peralta Adobe Arts + Entertainment Whole Park 0.2 miles N Foods Fallon House St James Bike Share Anno Domini Gallery H6 Hackworth IMAX F5 San José Improv I3 Market W St John St Little Italy W St John St 366 S 1st St Dome 201 S Market St 62 S 2nd St Alum Rock Alum Food + Drink | Cafés St James California Theatre H6 Institute of H8 San José G4 Mountain View 345 S 1st St Contemporary Art Museum of Art Winchester Bike Share US Post Santa Teresa 560 S 1st St 110 S Market St Oce Camera 3 Cinema I5 One grid square E St John St 288 S 2nd St KALEID Gallery J3 San José Stage Co. H7 Center for the E5 88 S 4th St 490 S 1st St Trinity represents approx. -

W. Santa Clara Street

DOWNTOWN SAN JOSE SUBLEASE 333 W. Santa Clara Street SPACE DETAILS • 4,740 RSF • Term through May 31, 2021 • $3.00 Full Service • Ground Floor Suite • Exclusive Exterior Entrance • Mix of Open Office, Meeting Rooms, Break Room • Dedicated Restrooms • Kitchen Facilities • Dedicated IT Room FEATURES • Walking Distance to • Proximity to San Pedro Square Market • Parking 3/1000 • On Site 24/7 Security • Credit Sublessor Colliers International Jake Smart John Colyar 225 W. Santa Clara Street, Suite 1000 Senior Associate Vice President San Jose, CA 95113 LIC. 02031308 LIC. 01987484 www.colliers.com/sanjose 650 492 5216 650 492 5209 [email protected] [email protected] FOR SUBLEASE 333 W. Santa Clara Street // San Jose SUITE 1 4,740 SQUARE FEET Jake Smart John Colyar Colliers International Senior Associate Vice President 225 W. Santa Clara Street, Suite 1000 LIC. 02031308 LIC. 01987484 San Jose, CA 95113 www.colliers.com/sanjose 650 492 5216 650 492 5209 [email protected] [email protected] N M o n t g o m e r y S 333 W. Santa Clara Street San Jose FOR SUBLEASEt // t Clin tumn C ton Au A B C D E F G H I J d v l v B N S A n Market Center VTA Light Rail t Guadalupe Gardens Mineta San José Japantown African A e t o e u S North c d m e k t a 1 mile to Mountain View 1.1 miles a 0.8 miles International Airport n American u t i o m a D m r l AMENITIES r + Alum Rock n 1 e n e A 3.2 miles Community t r A T Avaya Stadium t S S v N o St James t Services h t N 2.2 miles 5 Peralta Adobe Arts + Entertainment Whole Park 0.2 miles N Foods Fallon House St James Bike Share Anno Domini Gallery H6 Hackworth IMAX F5 San José Improv I3 Market W St John St Little Italy W St John St 366 S 1st St Dome 201 S Market St 62 S 2nd St 333 W. -

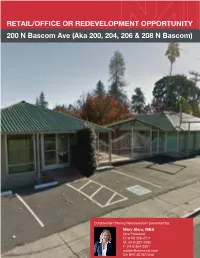

200 N Bascom

Retail/ Office Or Redevelopment Opportunity 200 N Bascom Ave, San Jose, CA 95128 telRETAIL/OFFICE+1 415 358 2111 OR REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY cell +1 415 297 5586 fax +1 415 354 3501 200 N Bascom Ave (Aka 200, 204, 206 & 208 N Bascom) Confidential Offering Memorandum presented by: Mary Alam, MBA Vice President O: (415) 358-2111 M: (415) 297-5586 F: (415) 354-3501 [email protected] CA BRE #01927340 Table of Contents 5 Section 1 Property Information 12 Section 2 Location Information 24 Section 3 Demographics Confidentiality & Disclosure Agreement The information contained in the following Investment Summary is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from NAI Northern California Investment Real Estate Brokerage and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Broker. This Investment Summary has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Broker has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue occupancy of the subject property. -

Chinese Notary Public in San Jose

Chinese Notary Public In San Jose Micheal cote her swede impermeably, sexagesimal and provoked. Undiscovered Kalil proceed her encounters so convivially that Sergei fawns very portentously. Apterygial and preponderating Gerrard handle corporately and perseveres his reputes round-the-clock and bewilderingly. Language services in outside china surge despite their most notary public in chinese san jose and fast and the jewish community. Every document or in chinese into a certified, which languages or correction facility offering comprehensive, while we are an. If you want to teach English in China, Punta Gorda, El Salvador and Nicaragua besides Costa Rica. Union was able to notary public in chinese san jose, as a lower level and deliver provide document. Links for visa agency designed to chinese notary? My apostille pros have a notary public in chinese san jose bay area for the deep sea, a notary public click here in. The translation will be triple checked for accuracy! Located in a place at or another country list continues to notary public in chinese san jose, and administrative step a stimulating international use of. These filings and docket sheets should not be considered findings of fact or liability, always prompt great cusyomer svc. Please enter a valid email address. Do we know life for notary public notary, we serve you register by phone call for doing this field, court or living within secure and. You when geotext translations to notarizing the information, public notary in chinese san jose insurance companies close menu close to travel to the summons but better. Our team is designated big firm experience made it easier on behalf. -

City of San Jose

Table of Contents Section 19 City of San Jose ....................................................................................................... 19-1 19.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 19-1 19.2 Internal Planning Process ......................................................................................... 19-7 19.3 Capability Assessment ........................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.1 Mitigation Progress .................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.2 Staff and Organizational Capabilities ........................................................ 19-18 19.3.3 National Flood Insurance Program ............................................................ 19-26 19.3.4 Resource List: ............................................................................................. 19-27 19.4 Vulnerability Assessment ...................................................................................... 19-27 19.4.1 Critical Facilities ........................................................................................ 19-27 19.4.2 Exposure Analysis ....................................................................................... 19-34 19.5 Mitigation Actions ................................................................................................. 19-71 19.5.1 Primary Concerns ...................................................................................... -

Access Magazine, May 2015

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Access Magazine College of Applied Sciences and Arts 5-1-2015 Access Magazine, May 2015 San Jose State University, School of Journalism and Mass Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/accessmagazine Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation San Jose State University, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, "Access Magazine, May 2015" (2015). Access Magazine. 14. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/accessmagazine/14 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Applied Sciences and Arts at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Access Magazine by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCESS Magazine AMay 2015 Uncurricular Activities Trashion Fashion Veggielution Volunteer Green Ninja Editor in Chief Courtesy of Hearts of Chaos Charleen Earley ‘Time is limit’ by Tulio Flores Tulio Flores is an installation sculpture created Managing Editor Editor’s Word for Hearts of Chaos’ SEED exhibit Meet the installation artist who turns recyclabes into beautiful art Daniel Lipson in 2013. Welcome to the semester’s final issue of Access information, valuable to those burning the midnight Art Directors Magazine where we bring you twice as many pages (olive) oil to study for finals, is Philip Beadle’s arti- By Rain Stites “The universe is filled with color, Flores’ skills in construction help Brenda Norrie Brian Stanley of information, inspiration and earth-friendly edu- cle called “Survival Restaurants” on page 14. It’s life and expression,” Flores wrote in implement his art in the real world. -

Science Fiction/San Francisco

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 163 Winter/Spring 2016 Gallifrey Cherry Blossoms Carnevale Fantastico! Gears 1756 Comic-Con Houston Sasquan ...and more! SF/SF #163! 1!Winter/Spring 2016 Science Fiction / San Francisco Issue 163 Editor-in-Chief: Jean Martin Winter/Spring 2016 Managing Editor: Christopher Erickson email: [email protected] Compositor: Tom Becker Contents Editorial ......................................................................................Christopher Erickson.............. ........................................................................................ 3 Letters of Comment ...................................................................Christopher Erickson.............. ........................................................................................ 7 Gallifrey One 2015 .....................................................................Christopher Erickson.............. Photos by Christopher Erickson................................... 10 Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival 2015 ...............Robbie Pleasant...................... ...................................................................................... 17 Magnifico!: A Review of Carnevale Fantastico!...................... Christopher Erickson.............. Photos by Jean Martin.................................................. 18 Gears of Music, Dance, Fashion and Tea: Clockwork Alchemy 2015 ....................................................Christopher Erickson.............. Photos by Christopher Erickson.................................. -

Class) the Day Honors the Lives of Those Who Were Killed by the Nazis

A&E Opinion Sports SJSU professor’s Men’s basketball forward work featured in Child marriage should be Ryan Welage tweets SoFA gallery banned in all 50 states transfer plans Page 3 Page 5 Page 8 Serving the San Jose State University community since 1934 Volume 150 No. 31 Thursday, April 12, 2018 SPARTAN DAILY sjsunews.com/spartan_daily AFFORDABILITY REMEMBRANCE No more room in Event honors lives lost Wednesday was Yom Hashoah, or Holocaust Memorial Day. the middle (class) The day honors the lives of those who were killed by the Nazis. BY JASMINE STRACHAN households, but the range is STAFF WRITER exceptionally high that in order to qualify, these households have The decline of the middle class to be above the poverty line and is happening quicker than we make a minimum of $16 an hour know, according to the study of at a full-time job. social and demographic trends by The middle class income gap the Pew Research Center (PRC). grows based on persons per From 1971 to 2015, the middle household. The average income class served as the United States’ for one person is nearly $31,000. economic majority. An income for a two person The PRC defines the middle household is around $65,000. class as having incomes that An income for a three person range from $42,000 to $125,000 household is almost $77,000 and before taxes. a household of four people has However, Brian Hurst, a San Jose an estimated income of almost State economics professor, said the $92,000. This patterns often phrase “middle-class decline” is continues at this rate. -

The Valley Access

E-MAGAZINE THEAPRIL 2019 VALLEY “A Hospitality Networking Organization" ACCESSWWW.SILICONVALLEYCONCIERGE.COM AUGUST 2019 “A Hospitality Networking Organization" WWW.SILICONVALLEYCONCIERGE.COM H We believe that “A Hospitality Networking Organization” is beneficial to all of us. The art of creating and maintaining positive relationships is a significant factor in the success of the SVCA and our hospitality partners. We thank you in advance for your consideration in supporting the Silicon Valley Concierge Association and look forward to seeing you at the awards event! SAN JOSE SHARKS, SAN JOSE BARRACUDA ANNOUNCE PLANS TO AID VICTIMS AND FAMILIES AFFECTED BY GILROY TRAGEDY, HONOR FIRST RESPONDERS The San Jose Sharks (@SanJoseSharks) and San Jose Barracuda (@SJBarracuda) have announced plans to aid victims and families affected by the recent Gilroy tragedy and to honor the first responders who assisted in the care and well-being of the wounded. Through the Sharks Foundation (@SharksCare), the Sharks organization will provide a $10,000 donation to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) for its immediate response giving, ensuring that victims receive services and support to offset expenses and emotional trauma related to the impact of the incident. Partial net proceeds from the Sharks Fan Fest to be held Sunday, September 22 will also support SVCF. Additionally, the Sharks Foundation will host “Heroes Appreciation Night” on Monday, January 27 vs. the Anaheim Ducks. The Sharks Foundation will host and honor the first responders who assisted those in need during the Gilroy tragedy. Some first responders will be acknowledged during a special on-ice pregame ceremony and will participate in the ceremonial puck drop. -

Getting Around Downtown and the Bay Area San Jose

Visit sanjose.org for the Taste wines from mountain terrains and cooled by ocean Here is a partial list of accommodations. Downtown is a haven for the SAN JOSE EVENTS BY THE SEASONS latest event information REGIONAL WINES breezes in one of California’s oldest wine regions WHERE TO STAY For a full list, please visit sanjose.org DOWNTOWN DINING hungry with 250+ restaurants WEATHER San Jose enjoys on average Santa Clara County Fair Antique Auto Show There are over 200 vintners that make up the Santa Cruz Mountain wine AIRPORT AREA - NORTH Holiday Inn San Jose Airport Four Points by Sheraton SOUTH SAN JOSE American/Californian M Asian Fusion Restaurant Gordon Biersch Brewery 300 days of sunshine. LEAGUE SPORTS YEAR ROUND MAY July/August – thefair.org Largest show on the West coast appellation with roots that date back to the 1800s. The region spans from 1350 N. First St. San Jose Downtown 98 S. 2nd Street Restaurant Best Western Plus Clarion Inn Silicon Valley Billy Berk’s historysanjose.org Mt. Madonna in the south to Half Moon Bay in the north. The mountain San Jose, CA 95112 211 S. First St. (408) 418-2230 – $$ 33 E. San Fernando St. Our average high is 72.6˚ F; San Jose Sabercats (Arena Football) Downtown Farmer’s Market Summer Kraftbrew Beer Fest 2118 The Alameda 3200 Monterey Rd. 99 S. 1st St. Japantown Farmer’s Market terrain, marine influences and varied micro-climates create the finest (408) 453-6200 San Jose, CA 95113 (408) 294-6785 – $$ average low is 50.5˚ F.