Censorship and Creative Freedom in Shostakovich’S Compositional Style: Music As a Tool for the State, Or the Soul?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

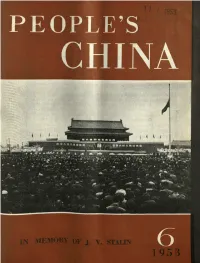

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

Building Cultural Bridges: Benjamin Britten and Russia

BUILDING CULTURAL BRIDGES: BENJAMIN BRITTEN AND RUSSIA Book Review of Benjamin Britten and Russia, by Cameron Pyke Maja Brlečić Benjamin Britten visited Soviet Russia during a time of great trial for Soviet artists and intellectuals. Between the years of 1963 and 1971, he made six trips, four formal and two private. During this time, the communist regime within the Soviet Union was at its heyday, and bureaucratization of culture served as a propaganda tool to gain totalitarian control over all spheres of public activity. This was also a period during which the international political situation was turbulent; the Cold War was at its height with ongoing issues of nuclear armaments, the tensions among the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom ebbed and flowed, and the atmosphere of unrest was heightened by the Vietnam War. It was not until the early 1990s that the Iron Curtain collapsed, and the Cold War finally ended. While the 1960s were economically and culturally prosperous for Western Europe, those same years were tough for communist Eastern Europe, where the people still suffered from the aftermath of Stalin thwarting any attempts of artistic openness and creativity. As a result, certain efforts were made to build cultural bridges between West and East, including efforts that were significantly aided by Britten’s engagements. In his book Benjamin Britten and Russia, Cameron Pyke portrays the bridging of the vast gulf achieved through Britten’s interactions with the Soviet Union, drawing skillfully from historical and cultural contextualization, Britten’s and Pears’s personal accounts, interviews, musical scores, a series of articles about Britten published in the Soviet Union, and discussions of cultural and political figures of the time.1 In the seven chapters of his book, Pyke brings to light the nature of Britten’s six visits and offers detailed accounts of Britten’s affection for Russian music and culture. -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

Aram Khachaturian

Boris Berezovsky ARAM KHACHATURIAN Boris Berezovsky has established a great reputation, both as the most powerful of Violin Sonata and Dances from Gayaneh & Spartacus virtuoso pianists and as a musician gifted with a unique insight and a great sensitivity. Born in Moscow, Boris Berezovsky studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Eliso Hideko Udagawa violin Virsaladze and privately with Alexander Satz. Subsequent to his London début at the Wigmore Hall in 1988, The Times described him as "an artist of exceptional promise, a player of dazzling virtuosity and formidable power". Two years later he won the Gold Boris Berezovsky piano Medal at the 1990 International Tchaïkovsky Competition in Moscow. Boris Berezovsky is regularly invited by the most prominent orchestras including the Philharmonia of London/Leonard Slatkin, the New York Philharmonic/Kurt Mazur, the Munich Philharmonic, Oslo Philharmonic, the Danish National Radio Symphony/Leif Segerstam, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony/Dmitri Kitaenko, the Birmingham Sympho- ny, the Berlin Symphonic Orchestra/ Marek Janowski, the Rotterdam Philharmonic, the Orchestre National de France. His partners in Chamber Music include Brigitte Engerer, Vadim Repin, Dmitri Makhtin, and Alexander Kniazev. Boris Berezovsky is often invited to the most prestigious international recitals series: The Berlin Philharmonic Piano serie, Concertgebouw International piano serie and the Royal Festival Hall Internatinal Piano series in London and to the great stages as the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, the Palace of fine Arts in Brussells, the Konzerthaus of Vienna, the Megaron in Athena. 12 NI 6269 NI 6269 1 Her recent CD with the Philharmonia Orchestra was released by Signum Records in 2010 to coincide with her recital in Cadogan Hall. -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

DSCH Journal No. 24

DOCUMENTARY III VARIANT AND VARIATION[1] IN THE SECOND MOVEMENT OF THE ELEVENTH SYMPHONY Lyudmila German The Eleventh Symphony, form, as it ‘resists’ develop- named Year 1905, is a pro- mental motif-work and frag- ach of Shostakovich’s gram work that relates the mentation. [2]” symphonies is unique in bloody events of the ninth of Eterms of design and January, 1905, when a large Indeed, if we look at the sec- structure. Despite the stifled number of workers carrying ond movement of the sym- atmosphere of censorship petitions to the Tsar were shot phony, for instance, we shall which imposed great con- and killed by the police in the see that its formal structure is strains, Shostakovich found Palace Square of St. Peters- entirely dependent on the nar- creative freedom in the inner burg. In order to symbolize rative and follows the unfold- workings of composition. the event Shostakovich chose ing of song quotations, their Choosing a classical form such a number of songs associated derivatives, and the original as symphony did not stultify with protest and revolution. material. This leads the com- the composer’s creativity, but The song quotations, together poser to a formal design that rather the opposite – it freed with the composer’s original is open-ended. There is no his imagination in regard to material, are fused into an final chord and the next form and dramaturgy within organic whole in a highly movement begins attacca. the strict formal shape of a individual manner. Some of The formal plan of the move- standard genre. -

Aram KHACHATURIAN (1903 – 1978) Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia From

Aram KHACHATURIAN (1903 – 1978) Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia from “Spartacus” Born into an Armenian family in Tbilisi in 1903, Aram Khachaturian's musical identity formed slowly. A tuba player in his school band and a self-taught pianist, he wanted to be a biologist and did not study music formally until entering Moscow's Gnesin Music Academy - as a cellist - in 1922. His considerable musical talents were soon manifested and, by 1925, he was studying composition. In 1929, Khachaturian joined Nikolai Miaskovsky's composition class at the Moscow Conservatory. Khachaturian graduated in 1934 and before the completion of his postgraduate studies, the successful premieres of such works as the Symphony No. 2 in a minor and the Piano Concerto in D-flat Major established him as the leading Soviet composer of his generation. During the vicious government-sponsored attacks on the Soviet Composers' Union in the late-1940s, Khachaturian withstood a great deal of criticism even though his music contained few of the objectionable traits found in the music of more adventuresome colleagues. In 1950, following a humble apology for his artistic "errors", he joined the composition faculty of the Moscow Conservatory and the Gnesin Academy. During the years until his death in 1978, Khachaturian made frequent European conducting appearances and, in January of 1968, made a culturally significant trip to Washington, D.C., to conduct the National Symphony Orchestra in a program of his own works. In addition to the aforementioned compositions, Khachaturian’s other works include film scores, songs, piano pieces, and chamber music. The degree of Khachaturian's success as a Soviet composer can be measured by his many honors, which include the 1941 Lenin Prize, the 1959 Stalin Prize, and title, in 1954, of People's Artist. -

Aram Khachaturian - Biography

Aram Khachaturian - Biography - The composer Aram Khachaturian, born in 1903 in Tiflis (Georgia) only decided on a musical career relatively late in life. He began his studies at the age of 19, first in the cello class of the Gnessin Musical-Technical School, then as a composition student. From 1930 he attended the Moscow Conservatory, studying with Miaskovsky (composition) and Vassilenko (orchestration). Each of his teachers imparted a different side of Russian music to him, respectively: through Vassilenko, Khachaturian made contact with "conservative" strivings, whereas in Miaskovsky he encountered a personality who was constantly on the lookout for the new. A third tendency, coming from his ancestry, was the integration of Armenian folklore. Khachaturian succeeded in connecting the folk music of his Armenian-Caucasian homeland with Russian art music. "I don't think I've written a single work not in some way bearing the stamp of the essence of folk culture and art." Above all, the ballet "Gayaneh" is the expression of this very personal, individual will. The "Sabre Dance" from it has become especially famous throughout the world. Khachaturian's breakthrough as a composer, however, already occurred in 1933/34 with the world premiere of his First Symphony and the Piano Concerto, a work played today all over the world. In 1951 he became Professor of Composition at the Moscow Conservatory and advanced to Secretary of the Composers' Union of the Soviet Union in 1957. Already many years prior to this he had made a name for himself as a conductor and made guest appearances in this capacity in the West starting in the mid-1970s. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln. -

Link Shostakovich.Txt

FRAMMENTI DELL'OPERA "TESTIMONIANZA" DI VOLKOV: http://www.francescomariacolombo.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=54&Itemid=65&lang=it LA BIOGRAFIA DEL MUSICISTA DA "SOSTAKOVIC" DI FRANCO PULCINI: http://books.google.it/books?id=2vim5XnmcDUC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=testimonianza+v olkov&source=bl&ots=iq2gzJOa7_&sig=3Y_drOErxYxehd6cjNO7R6ThVFM&hl=it&sa=X&ei=yUi SUbVkzMQ9t9mA2A0&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=testimonianza%20volkov&f=false LA PASSIONE PER IL CALCIO http://www.storiedicalcio.altervista.org/calcio_sostakovic.html CENNI SULLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.52composers.com/shostakovich.html PERSONALITA' DEL MUSICISTA NELL'APPOSITO PARAGRAFO "PERSONALITY" : http://www.classiccat.net/shostakovich_d/biography.php SCHEMA MOLTO SINTETICO DELLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/dmitry-shostakovich-344.php La mia droga si chiama Caterina La mia droga si chiama Caterina “Io mi aggiro tra gli uomini come fossero frammenti di uomini” (Nietzsche) In un articolo del 1932 sulla rivista “Sovetskoe iskusstvo”, Sostakovic dichiarava il proprio amore per Katerina Lvovna Izmajlova, la protagonista dell’opera che egli stava scrivendo da oltre venti mesi, e che vedrà la luce al Teatro Malyi di Leningrado il 22 gennaio 1934. Katerina è una ragazza russa della stessa età del compositore, ventiquattro, venticinque anni (la maturazione artistica di Sostakovic fu, com’è noto, precocissima), “dotata, intelligente e superiore alla media, la quale rovina la propria vita a causa dell’opprimente posizione cui la Russia prerivoluzionaria la assoggetta”. E’ un’omicida, anzi un vero e proprio serial killer al femminile; e tuttavia Sostakovic denuncia quanta simpatia provi per lei. Nelle originarie intenzioni dell’autore, “Una Lady Macbeth del distretto di Mcensk” avrebbe inaugurato una trilogia dedicata alla donna russa, còlta nella sua essenza immutabile attraverso differenti epoche storiche.