Induction of Seedlessness in Citrus: from Classical Techniques to Emerging Biotechnological Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Acid Citrus Selections for Florida

New acid citrus selections for Florida Lemon and lime-like selections with niche market potential are being developed with biotechnology at the University of Florida. By Jude Grosser, Zenaida Viloria and Manjul Dutt re you ready for a purple margarita? Would you like a fragrant, juicy lime is a naturally occurring citrus lemon for your iced tea with no seeds to clog your straw or dishwasher triploid, which is why it is seedless. drain? How about some seedless lime trees that are cold-hardy enough The new seedless watermelons in the Afor Central Florida? These and many more interesting acid-citrus marketplace are also triploids. selections are now on the horizon, including some with good ornamental potential. Due to the fact that new and This article will focus on progress in using emerging biotechnologies to develop improved citrus cultivars must be interesting new citrus cultivars in the lemon and lime group. Cultivars include seedless to compete in the national some that will not have regulatory constraints, and also a genetically modified and international marketplace, the organism (GMO)-derived purple Key lime as a teaser for the future. University of Florida’s Citrus Research and Education Center (UF/CREC) LEARNING FROM they are triploids. People and most citrus improvement team (working THE BANANA citrus trees are diploid, meaning with Fred Gmitter) has formulated Have you ever wondered why you there are two sets of chromosomes in several ways to create triploids as a key never find seeds in your bananas? Did each cell. Triploid bananas have three method of developing seedless citrus you know that there are wild-type sets of chromosomes per cell. -

New Citrus Varieties Fort Bend County Master Gardeners

New Citrus Varieties Fort Bend County Master Gardeners Fruit Tree Sale, February 9, 2019 Written by Deborah Birge, Fort Bend County Master Gardener Citrus is one of the most sought-after fruit trees for residents of Fort Bend County. Nothing is more intoxicating than a tree full of orange or lemon blossoms. Nothing more inviting than a tree full of tasty oranges or satsumas ready for the picking. Citrus can be cold hardy needing little winter care or very cold sensitive needing protection from temperatures below 40 degrees. Choosing the variety for your particular needs and interest can be accomplished by understanding the many varieties and their properties. Fort Bend County Master Gardeners will be offering several new citrus varieties at the Annual Fruit Tree Sale, February 9, 2019. We have a new pommelo, lime, three mandarins, and a grapefruit. This article will discuss each to help you in your decisions. Australian Finger Lime The Australian finger lime is described as Citrus Caviar. These small cucumber-shaped limes are practically in a category all their own. Their aromatic skin appears in a triad of colors and the flesh holds caviar- shaped vesicles that pop crisply in your mouth with an assertively tart punch. The tree is a small-leafed understory plant with some thorns. The tough climate conditions of the Australian coastal regions where Finger Limes were first grown make it suitable for a diversity of planting locations with little care or maintenance. It will even tolerate cooler weather down to a brief frost. Its compact, almost hedge-like stature make it an excellent candidate for tight spots in the garden or throughout the landscape. -

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 1

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Lecture 32 Citrus Citrus: Citrus spp., Rutaceae Citrus are subtropical, evergreen plants originating in southeast Asia and the Malay archipelago but the precise origins are obscure. There are about 1600 species in the subfamily Aurantioideae. The tribe Citreae has 13 genera, most of which are graft and cross compatible with the genus Citrus. There are some tropical species (pomelo). All Citrus combined are the most important fruit crop next to grape. 1 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 The common features are a superior ovary on a raised disc, transparent (pellucid) dots on leaves, and the presence of aromatic oils in leaves and fruits. Citrus has increased in importance in the United States with the development of frozen concentrate which is much superior to canned citrus juice. Per-capita consumption in the US is extremely high. Citrus mitis (calamondin), a miniature orange, is widely grown as an ornamental house pot plant. History Citrus is first mentioned in Chinese literature in 2200 BCE. First citrus in Europe seems to have been the citron, a fruit which has religious significance in Jewish festivals. Mentioned in 310 BCE by Theophrastus. Lemons and limes and sour orange may have been mutations of the citron. The Romans grew sour orange and lemons in 50–100 CE; the first mention of sweet orange in Europe was made in 1400. Columbus brought citrus on his second voyage in 1493 and the first plantation started in Haiti. In 1565 the first citrus was brought to the US in Saint Augustine. 2 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Taxonomy Citrus classification based on morphology of mature fruit (e.g. -

Tangerines, Mandarins, Satsumas, and Tangelos

Tangerines, Mandarins, Satsumas, and Tangelos Category: Semi-evergreen Hardiness: Damage will occur when temperatures drop below the low 20’s Fruit Family: Citrus Light: Full sun to half day sun Size: 10’H x 10’W; may be pruned to desired HxW Soil: Well-drained Planting: Plant after danger of frost has passed, mid to late March The name “tangerine” derives from one variety that was imported to Europe from Tangiers. There are many named varieties of what citrus growers call “mandarins” because of their Asian origins. One of these, the “Satsuma”, is an heirloom Japanese mandarin that is both delicious and especially adapted to Southeast Texas. It has been part of Gulf Coast Citrus history for a century. There are many named varieties of Satsumas. Mandarins are mostly orange-fleshed, juicy, highly productive, very easy to care for, long-lived, easily peeled and segmented or juiced. Few fruits can match the mandarin. Satsumas are seedless or close to seedless. They are all of outstanding quality and differ little among themselves except for when they ripen. Buy early, mid and late season varieties to have months of ripe fruit harvests from September to April. Care of Mandarins and related fruits Planting: Newly purchased citrus have probably not been hardened off to tolerate our winter weather. Keep your citrus in the container until late March, or until all danger of freeze has passed. Trees can be kept outside in a sunny area on mild days and nights, but move them into the shelter of the garage or house if frost is predicted. -

Facts About Citrus Fruits and Juices: Grapefruit1 Gail C

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. FSHN02-6 Facts About Citrus Fruits and Juices: Grapefruit1 Gail C. Rampersaud2 Grapefruit is a medium- to large-sized citrus fruit. It is larger than most oranges and the fruit may be flattened at both ends. The skin is mostly yellow but may include shades of green, white, or pink. Skin color is not a sign of ripeness. Grapefruit are fully ripe when picked. Popular varieties of Florida grapefruit include: Did you know… Marsh White - white to amber colored flesh and almost seedless. Grapefruit was first Ruby Red - pink to reddish colored flesh with few seeds. discovered in the West Flame - red flesh and mostly seedless. Indies and introduced to Florida in the 1820s. Most grapefruit in the U.S. is still grown in Florida. Compared to most citrus fruits, grapefruit have an extended growing season and several Florida Grapefruit got its name because it grows in varieties grow from September through June. clusters on the tree, just like grapes! Fresh citrus can be stored in any cool, dry place but will last longer if stored in the refrigerator. Do Imposter!! not store fresh grapefruit in plastic bags or film- wrapped trays since this may cause mold to grow on the fruit. Whether you choose white or pink grapefruit or grapefruit juice, you’ll get great taste and a variety of health benefits! Read on…. 1. This document is FSHN026, one of a series of the Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Canker Resistance: Lesson from Kumquat by Naveen Kumar, Bob Ebel the Development of Asiatic Citrus Throughout Their Evolution, Plants and P.D

Canker resistance: lesson from kumquat By Naveen Kumar, Bob Ebel The development of Asiatic citrus Throughout their evolution, plants and P.D. Roberts canker in kumquat leaves produced have developed many defense mecha- anthomonas citri pv. citri (Xcc) localized yellowing (5 DAI) or necro- nisms against pathogens. One of the is the causal agent of one of sis (9-12 DAI) that was restricted to most characteristic features associated the most serious citrus diseases the actual site of inoculation 7-12 DAI with disease resistance against entry X (Fig. 2). of a pathogen is the production of worldwide, Asiatic citrus canker. In the United States, Florida experienced In contrast, grapefruit epidermis hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Hydrogen three major outbreaks of Asiatic citrus became raised (5 DAI), spongy (5 peroxide is toxic to both plant and canker in 1910, 1984 and 1995, and it DAI) and ruptured from 7 to 8 DAI. pathogen and thus restricts the spread is a constant threat to the $9 billion On 12 DAI, the epidermis of grape- by directly killing the pathogen and citrus industry. fruit was thickened, corky, and turned the infected plant tissue. Hydrogen Citrus genotypes can be classified brown on the upper side of the leaves. peroxide concentrations in Xcc-in- into four broad classes based on sus- Disease development and popula- fected kumquat and grapefruit leaves ceptibility to canker. First, the highly- tion dynamics studies have shown that were different. Kumquat produces susceptible commercial genotypes are kumquat demonstrated both disease more than three times the amount of Key lime, grapefruit and sweet lime. -

Citrus from Seed?

Which citrus fruits will come true to type Orogrande, Tomatera, Fina, Nour, Hernandina, Clementard.) from seed? Ellendale Tom McClendon writes in Hardy Citrus Encore for the South East: Fortune Fremont (50% monoembryonic) “Most common citrus such as oranges, Temple grapefruit, lemons and most mandarins Ugli Umatilla are polyembryonic and will come true to Wilking type. Because most citrus have this trait, Highly polyembryonic citrus types : will mostly hybridization can be very difficult to produce nucellar polyembryonic seeds that will grow true to type. achieve…. This unique characteristic Citrus × aurantiifolia Mexican lime (Key lime, West allows amateurs to grow citrus from seed, Indian lime) something you can’t do with, say, Citrus × insitorum (×Citroncirus webberii) Citranges, such as Rusk, Troyer etc. apples.” [12*] Citrus × jambhiri ‘Rough lemon’, ‘Rangpur’ lime, ‘Otaheite’ lime Monoembryonic (don’t come true) Citrus × limettioides Palestine lime (Indian sweet lime) Citrus × microcarpa ‘Calamondin’ Meyer Lemon Citrus × paradisi Grapefruit (Marsh, Star Ruby, Nagami Kumquat Redblush, Chironja, Smooth Flat Seville) Marumi Kumquat Citrus × sinensis Sweet oranges (Blonde, navel and Pummelos blood oranges) Temple Tangor Citrus amblycarpa 'Nasnaran' mandarin Clementine Mandarin Citrus depressa ‘Shekwasha’ mandarin Citrus karna ‘Karna’, ‘Khatta’ Poncirus Trifoliata Citrus kinokuni ‘Kishu mandarin’ Citrus lycopersicaeformis ‘Kokni’ or ‘Monkey mandarin’ Polyembryonic (come true) Citrus macrophylla ‘Alemow’ Most Oranges Citrus reshni ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin Changshou Kumquat Citrus sunki (Citrus reticulata var. austera) Sour mandarin Meiwa Kumquat (mostly polyembryonic) Citrus trifoliata (Poncirus trifoliata) Trifoliate orange Most Satsumas and Tangerines The following mandarin varieties are polyembryonic: Most Lemons Dancy Most Limes Emperor Grapefruits Empress Tangelos Fairchild Kinnow Highly monoembryonic citrus types: Mediterranean (Avana, Tardivo di Ciaculli) Will produce zygotic monoembryonic seeds that will not Naartje come true to type. -

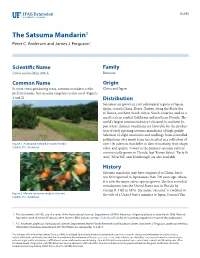

The Satsuma Mandarin1 Peter C

HS195 The Satsuma Mandarin1 Peter C. Andersen and James J. Ferguson2 Scientific Name Family Citrus unshiu Marcovitch Rutaceae Common Name Origin In most citrus producing areas, satsuma mandarin is the China and Japan preferred name, but satsuma tangerine is also used (Figures 1 and 2). Distribution Satsumas are grown in cool subtropical regions of Japan, Spain, central China, Korea, Turkey, along the Black Sea in Russia, southern South Africa, South America, and on a small scale in central California and northern Florida. The world’s largest satsuma industry is located in southern Ja- pan where climatic conditions are favorable for the produc- tion of early ripening satsuma mandarins of high quality. Selection of slight mutations and seedlings from controlled pollinations over many years has resulted in a collection of Figure 1. A satsuma orchard in north Florida. over 100 cultivars that differ in date of maturity, fruit shape, Credits: P. C. Andersen color, and quality. ‘Owari’ is the primary satsuma cultivar commercially grown in Florida, but ‘Brown Select’, ‘Early St. Ann’, ‘Silverhill’, and ‘Kimbrough’ are also available. History Satsuma mandarin may have originated in China, but it was first reported in Japan more than 700 years ago, where it is now the major citrus species grown. The first recorded introduction into the United States was in Florida by George R. Hall in 1876. The name “satsuma” is credited to Figure 2. Mature satsumas ready for harvest. the wife of a United States minister to Japan, General Van Credits: P. C. Andersen 1. This document is HS195, one of a series of the Horticultural Sciences Department, UF/IFAS Extension. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Molecular Genetic Approach to Evaluate a Novel Seedless Phenotype Found in Tango, a New Variety of Mandarin Developed From Gamma-Irradiated W. Murcott Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1gp2m8vb Author Crowley, Jennifer Robyn Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE A Molecular Genetic Approach to Evaluate a Novel Seedless Phenotype Found in Tango, a New Variety of Mandarin Developed From Gamma-Irradiated W. Murcott Doctor of Philosophy in Genetics, Genomics and Bioinformatics by Jennifer Robyn Crowley December 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Mikeal Roose, Chairperson Dr. Linda Walling Dr. Katherine Borkovich Copyright by Jennifer Robyn Crowley 2011 The Dissertation of Jennifer Robyn Crowley is approved: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and give my many thanks to several people who contributed both their time and their effort towards my dissertation work. I would like to thank Dr. David Carter for his instruction regarding the correct use of the Leica SP2 confocal microscope, as well as for his help in gathering quality computerized images. I would like to thank Dr. Chandrika Ramadugu and Dr. Manjunath Keremane for their assistance with the use of the Stratagene MX thermocycler, as well as for their help in qPCR data interpretation. To Dr. Chandrika Ramadugu, I would also like to extend my gratitude for the contribution she made towards my research project by providing me with clones of a DNA sequence of interest. -

Improvement of Subtropical Fruit Crops: Citrus

IMPROVEMENT OF SUBTROPICAL FRUIT CROPS: CITRUS HAMILTON P. ÏRAUB, Senior Iloriiciilturist T. RALPH ROBCNSON, Senior Physiolo- gist Division of Frnil and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Tndusiry MORE than half of the 13 fruit crops known to have been cultivated longer than 4,000 years,according to the researches of DeCandolle (7)\ are tropical and subtropical fruits—mango, oliv^e, fig, date, banana, jujube, and pomegranate. The citrus fruits as a group, the lychee, and the persimmon have been cultivated for thousands of years in the Orient; the avocado and papaya were important food crops in the American Tropics and subtropics long before the discovery of the New World. Other types, such as the pineapple, granadilla, cherimoya, jaboticaba, etc., are of more recent introduction, and some of these have not received the attention of the plant breeder to any appreciable extent. Through the centuries preceding recorded history and up to recent times, progress in the improvement of most subtropical fruits was accomplished by the trial-error method, which is crude and usually expensive if measured by modern standards. With the general accept- ance of the Mendelian principles of heredity—unit characters, domi- nance, and segregation—early in the twentieth century a starting point was provided for the development of a truly modern science of genetics. In this article it is the purpose to consider how subtropical citrus fruit crops have been improved, are now being improved, or are likel3^ to be improved by scientific breeding. Each of the more important crops will be considered more or less in detail. -

Parthenocarpy and Functional Sterility in Tomato

Parthenocarpy and functional sterility in tomato Benoit Gorguet Promotor: Prof. Dr. R.G.F. Visser Hoogleraar in de Plantenveredeling, Wageningen Universiteit Co-promotor: Dr. ir. A.W. van Heusden Wetenschappelijk onderzoeker, Laboratorium voor Plantenveredeling, Wageningen Universiteit Promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. C.T. Mariani, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Prof. Dr. Ir. M. Koornneef, Wageningen Universiteit Dr. A.G. Bovy, Plant Research International, Wageningen Prof. Dr. O. van Kooten, Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoekschool ‘Experimental Plant Sciences’ Parthenocarpy and functional sterility in tomato Benoit Gorguet Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 16 november 2007 des namiddags te 13:30 in de Aula Parthenocarpy and functional sterility in tomato Benoit Gorguet PhD thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands, 2007 With summaries in English, Dutch and French ISBN 978-90-8504-762-9 CONTENTS Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. 7 Preface ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Chapter 1 ……………………………………………………………………. 13 Parthenocarpic fruit development in tomato – A review Chapter 2 ……………………………………………………………………. 29 Bigenic control of parthenocarpy in tomato Chapter 3 ……………………………………………………………………. 51 High-resolution fine mapping of ps-2, a mutated gene conferring functional male sterility in tomato due to non-dehiscent anthers Chapter 4 ……………………………………………………………………. -

Parthenocarpy in Summer Squash on a Lima Silt Loam (Fine-Loamy, Mixed, Mesic, Glossoboric Hapludalf) at Geneva, N.Y

HORTSCIENCE 34(4):715–717. 1999. Materials and Methods Experiments were conducted for 4 years Parthenocarpy in Summer Squash on a Lima silt loam (fine-loamy, mixed, mesic, Glossoboric Hapludalf) at Geneva, N.Y. Four- 1 2 R.W. Robinson and Stephen Reiners week-old transplants were set in the field and Department of Horticultural Sciences, New York State Agricultural Experiment spaced at 0.9 m in rows on 1.5-m centers. Station, Geneva, NY 14456-0462 Weeds were controlled using recommended herbicides, cultivation, and hand weeding, Additional index words. Cucurbita pepo, fruit set, seedless fruit, row covers, pollination while insect and disease pressure was moni- tored and protective treatments applied when Abstract. Summer squash (Cucurbita pepo L.) cultivars were compared for ability to set warranted (Becker, 1992). parthenocarpic fruit. Some cultivars set no parthenocarpic fruit and others varied in the Over 95% of the first pistillate flowers to amount of fruit set when not pollinated. The degree of parthenocarpy varied with season, develop were closed before anthesis by plac- but the relative ranking of cultivars for parthenocarpy was generally similar. Cultivars ing plastic-covered wire around the unopened with the best parthenocarpic fruit set were of the dark green, zucchini type, but some petals to prevent insect pollination. Any open cultivars of other fruit types also set parthenocarpic fruit. A summer squash cultivar was flowers were removed within 2 d of anthesis to developed that combines a high rate of natural parthenocarpy with multiple disease prevent development of open-pollinated fruit. resistance. Yield of summer squash plants grown under row covers that excluded Fruit from closed flowers were harvested im- pollinating insects was as much as 83% of that of insect-pollinated plants in the open.